Emily Jacobs McClatchey (’00) was 11 years old when her beloved family dog, Muppet, died. Her parents thought they were doing the right thing when they quickly removed any signs of Muppet to “protect” her from further heartache.

But McClatchey needed to grieve and remember Muppet, so she created a memory box with Muppet’s collar, pictures and other keepsakes that she still has at her parents’ house.

McClatchey, now 39, grew up to become a child psychologist and therapist. After years spent helping children cope with loss, she knows that many well-meaning adults don’t know how to support grieving children. She’s taken her role as a therapist in a different direction and found a new way to help kids. She’s started a company called Kidolences that makes keepsake care boxes for kids who have suffered a loss.

The loss of a friend/sibling box includes a bedside light, angel wings, a feelings journal and a photo album.

It’s a way adults can help children express their feelings, remember their loved one and cope with change, said McClatchey, who lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “This is a thoroughly thought-through, developmentally appropriate, clinically proven way to let a child know that you’re thinking about them in their time of loss.”

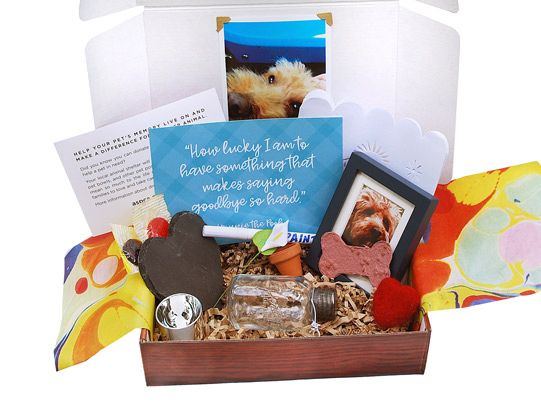

Kidolences offers customized care boxes for the loss of a family member, friend or pet, or a stressful life change, such as moving or divorce. The boxes are filled with goodies and age-appropriate keepsakes, depending on the circumstances, such as a picture frame, a journal, forget-me-not seeds and a coloring mandala

The care boxes “provide space for a private, individualized story of loss to be told,” McClatchey said. Children, especially, have a need to tell stories and collect mementos to help them remember their loved one, she said. And “there’s just something cool about collecting your memories in a shoebox.”

Emily Jacobs McClatchey ('00)

McClatchey was a member of Chi Omega sorority and a psychology major at Wake Forest. After graduating, she served in the Peace Corps in Jamaica, where she worked with at-risk and traumatized kids. She researched child survivors of the Holocaust while working on her master’s and Ph.D. in psychology at New York University. She went on to a career as a school psychologist, as a child and family therapist and with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

McClatchey hit “life’s big reset” button when her third child was born with a heart defect that required surgery when he was eight days old. She had spent her career counseling families in similar situations, but she struggled to help her family cope. It’s different when it happens to you, she notes. (Her son, Devereaux, 2, is doing well now.)

She quit her job as a therapist to spend more time with her son and two daughters and to ponder what she should do next. The idea hit her in the middle of the night in July: She could use her education and research — and her own family’s experience dealing with a serious illness — in a different way by creating care boxes for kids. (She registered the Kidolences website name at 4:22 that morning.) The box she created for Muppet when she was 11 years old sparked some of her ideas.

McClatchey's most popular care box is for the loss of a pet and is most often purchased for adults.

Most of us experience our first loss — the death of a pet or grandparent, for example — as children, she notes. When adults suffer a loss, we know how to respond: flowers, a sympathy card, a home-cooked meal. With children, adults too often try to shield them from grief or don’t do anything for fear of saying or doing the wrong thing. But children need to know that adults acknowledge their loss and care about them, she said. She has a list of books on her website to help children cope with loss, illness and divorce.

“Children’s losses are often marginalized, despite the fact that their experiences are not only valid, but deeply formative, shaping the kind of adults they will become,” she said. “Children are innately deeply feeling, compassionate and wired for connection. How we respond to a child’s suffering communicates a lot to them about how the world works. If we can honor their experience, we have communicated that the world is a loving, kind place.”

Foster-care child box<br />

McClatchey also makes two “lighter side” boxes to help kids welcome a new brother or sister into the family or say “goodbye” to their pacifier. She also has a care box for children in foster care that people can buy and donate to foster-care child services in their town. The box might be the only thing that foster kids can call their own, she said.

For now, McClatchey is operating in the back of a friend’s florist shop, with the help of a graphic designer. She is donating 5 percent of profits to the Dougy Center, a nonprofit in Portland, Oregon, that supports grieving children and their families.

“Our goal is not to take away their pain,” she said. “Our goal is to say goodbyes are a part of life, pain is a part of life. We want to give kids some sense of comfort and let them know that they’re not alone, and we care about them and are thinking about them.”

Parent-loss box

“The unthinkable has happened, and some wonderful soul has ordered this box to try to help a child who is suffering in unthinkable ways. As I am packing the box, I am gazing at whatever beautiful photo has been uploaded to be placed in the box and just praying that this box hits the mark and communicates ‘I am here, I am thinking of you, I love you, I know you are strong.’”

A “lighter side” box helps kids welcome a new brother or sister into the family.