JUSTIN BRICE GUARIGLIA (’97) explores an ecological crisis, working at the nexus of photography, painting, relief sculpture and printmaking, while challenging us to take the holistic view.

Photo by Noah Kalina

Something is happening here. A vast canvas of white, its ripples and swirls frothed like peaks of meringue. A vast canvas of black, studded with what appears to be shimmering starburst.

Look closely.

That’s what Justin Brice Guariglia (’97) asks of you.

Since he left Wake Forest he has traveled by air and overland, across the rice paddies and beaches of Bali, into the secretive Shaolin Temple of sacred martial arts in China and among the people bustling through marketplaces in Shanghai. He has taken you with him, the photographer on assignment for National Geographic, National Geographic Traveler and Smithsonian magazines, on expeditions that allowed you to examine, clear-eyed and captivated, the cultural treasures of the world.

Look closely once more. The canvases of white and of black might not be what you think. Here in Guariglia’s studio in Brooklyn, New York, nearer to bleak highway interchanges than to chichi brownstone boutiques, you can examine the clues strewn about a room that feels like a warehouse. A toy dinosaur. A sign: “Warning! Imminent Flood Zone.” Shelves stocked with books — biologist E.O. Wilson’s “Nature Revealed: Selected Writings, 1949-2006;” futurist Ray Kurzweil’s “The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology;” “Natural Wonders of the World;” “Taoism;” and Amy Cuddy’s “Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges.” Pinned to a bulletin board is an 8 ½ x 11” paper with a pencil-scrawled heading: “Questioning of Life’s Purpose.” Beneath the heading are: “Pinnacle of Civilization?,” “Humanities,” “The Whole Earth,” “Existential Risks,” “Feedback Loops” and “Terrestrial Agency” — all (and more) scratched out as if sparked by a creative jolt.

Photo by Noah Kalina

Perhaps the clues most telling of all are the jagged, black-carbon tattoo lines running up both of Guariglia’s arms, wrists to biceps, which hint at the baseball player Guariglia once was. The left arm’s tattoo represents the CO2 index — 650,000 years of carbon dioxide data from an ice core in Antarctica; the right, NASA’s GISTEMP index, tracking global temperature rise recorded from 1880 until 2016.

Something is happening here on the planet that led Guariglia to move from his work as a photojournalist and documentarian to become a self-described “transdisciplinary artist” intent on weaving science, art and philosophy into his work. He is a sentry and, at times, himself a philosopher mulling permanence, impermanence and our fragile coexistence on the planet known as home.

This studio reflects Guariglia’s reinvention of himself and his work beyond photography. Hanging on walls and leaning against them are oversized panels, layered with traditional painters’ gesso, with images printed using acrylic inks in a painstaking process Guariglia pioneered on a UV printer the size of four picnic tables. The inkjet technology allows Guariglia to put acrylic onto the panels, expose it to

UV light, cure it and then take the art in myriad directions. For some works that means sanding them down; others are built up with acrylic paints and acrylic ink. Every series uses a different technique and process.

Photo by Noah Kalina

Art historian and cultural journalist Carol Strickland reviewed Guariglia’s solo exhibition, “After Nature,” at TwoThirtyOne Projects in New York City and explained Guariglia’s process for this particular series on The Clyde Fitch Report arts website in May: “In order to restore power to the printed image, Guariglia needed to infuse it with the tactility of relief sculpture and the complexity and metaphorical depth of fine-art painting. … The photographs, composed of many strata — each layer hand-sanded — have depth and texture, seeming almost holographic. They are printed with up to 140 layers of acrylic ink on 25 layers of gesso and attached to substrates like polystyrene or aluminum, giving them literal depth. Exposure to ultraviolet radiation polymerizes the images, fixed in a form that will endure for eons.”

Acrylic on polystyrene, Guariglia notes, is derived from “fossil fuel on top of a fossil fuel” derivative. Materials like polystyrene or objects made of aluminum, unlike the glaciers, will go on “almost forever.” He points to one of his artworks in the studio: “Therein lies the irony. … The ice in that picture is gone. It’s out here,” he says, pointing toward the door. “It’s in Brooklyn. It’s in the water that’s lapping up on the shores of North Carolina.”

Justin Brice Guariglia, "QAANAAQ1," 2015-2016.

At their core these white works of art — “I call them paintings derived from photography” — document the melting landscapes of Greenland. The black ones might appear to be the night sky, but they are not the heavens. They depict the ocean, where Greenland’s sea ice is transforming, and remnants drift by. “That’s 100,000-year-old ice,” says Guariglia. “So now that’s melted. The molecules are all spread out in the ocean, but now it’s preserved forever in this picture.”

Last year Earth’s surface temperatures were the warmest since modern record-keeping began in 1880. Guariglia (pronounced “Gwah-rig-lee-ah”) views this global warming as an ecological crisis that demands a response at all levels, including by artists. He began noodling his ideas about how to confront the crisis about seven or eight years ago. He read about evolutionary theory, started speaking with scientists and delving more deeply into climate-change data and humans’ impact on the environment.

"How do you make something visceral? How do you take a concept and make it felt?"

“You talk to geologists. You start to get a better understanding of how we’ve evolved as humans, and you realize, OK, we’ve evolved to take care of our most basic of needs,” he says, “but we’ve not evolved to understand what the consequences are for all the actions.” One example he gives: a Styrofoam cup serves its purpose but won’t biodegrade anytime soon. Neither, he says, will his artwork, purposely printed on materials selected to make the point that they will outlast you.

About the same time he was digging into the science, he watched as digital photography exploded by technological leaps. It meant, he says, “more people running around with cameras able to execute imagery and make photographs that were technically good.” But in his view, such advances did not bode well for him and his craft: “Over the last five to 10 years, photography has been eviscerated through technology and just the sheer ubiquity of imagery. We’re drowning in social media streams. We’re bombarded by so many images today. Nobody needs to see another image.”

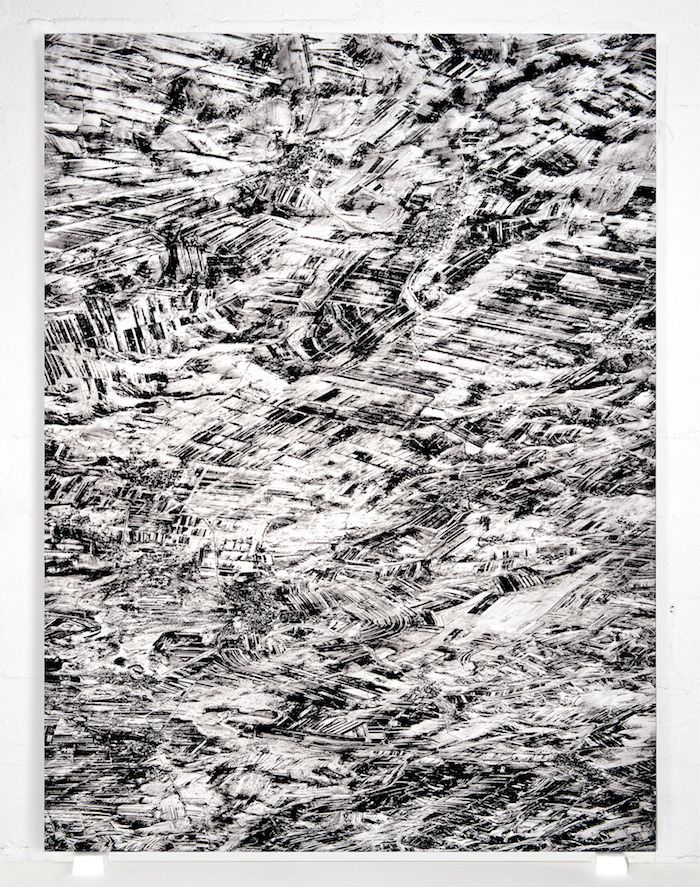

Justin Brice Guariglia, "ÖBÜR I," 2011-2015.

The situation posed a challenge. How might he expand what he calls his “vocabulary as a photographer?” How could he layer his experiences traveling the world, living for nearly two decades in Asian cultures, documenting the things he had seen into new processes that would “make the image resonate again?” How could he use scale to convey his ideas? He looks around his studio. “Everything in here is essentially a response to that.”

Guariglia’s artworks, which range in size from 30” x 40” to 16’ x 12’, seek to answer that question. Thirty new and recent works are on display through Jan. 7 at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida, in an exhibition titled “Earth Works: Mapping the Anthropocene.” The museum refers to the Anthropocene as “the age in which humans’ permanent mark on the entire planet, from the far reaches of the atmosphere to the lowest depths of the ocean — represents a new era in geologic history.” The images, according to the museum, “serve to illustrate with visual evidence, and through metaphor, the complexity of human impact on the planet.”

The exhibition has another draw — Guariglia’s work is distinctive in that its origins are linked to NASA.

The Greenland paintings began to take shape after Guariglia secured permission from NASA to fly with scientists taking measurements of Earth’s polar changes. It was fall of 2015. Guariglia, relying on his photojournalist street smarts, connections and ability to jump at a moment’s notice, heard a flight was imminent, so he packed his bag and was in Greenland in 48 hours, ready to go. In 2015 and 2016 he flew seven times with NASA as part of the Operation IceBridge mission, and he will be flying this year in a collaboration with Oceans Melting Greenland, or as NASA climate scientist and its principal investigator Josh Willis says, “OMG, for short.” The latter is a five-year mission by ship and by air to measure how much the oceans are melting away the ice in Greenland. Scientists use radar to measure the height of the ice and look for retreat of the glaciers in different regions. They measure the saltiness of the ocean and the temperatures.

“Greenland contains enough ice to raise sea levels by 20 feet if it all melted today, and it’s melting pretty quickly right now,” Willis says. “It accounts for about one-sixth of modern-day, global sea level rise.” With the melt-rate increasing, he says, “the big question for the future is: How fast is this going to happen?”

"What does this mean on a broader scale for humanity? As opposed to 'Oh, it's getting hot and the ice is melting.'"

He doesn’t hesitate to describe the larger context for his work and, by extension, Guariglia’s. “Just so we’re clear, human activities are changing the climate as we know it. And they’re making the planet warmer. It’s making sea levels rise. It’s changing the acidity of oceans, and these are big changes — things that as a civilization we haven’t lived through before. So there’s something really big going on, and it’s the result of human activity. We can say that — unequivocally. And personally, I think it’s time for us to start figuring out what to do about it.”

Based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, Willis has had “a lot of conversations” with Guariglia about the science and data. He credits Guariglia for trying to connect with people emotionally about the subject and “helping scientists tell our stories.” Scientists do well communicating with each other but not always with the general public, he says. That’s where artists can step in.

Joe MacGregor, deputy project scientist for Operation IceBridge at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, echoes Willis’ assessment. Operation IceBridge is an airborne mission to survey polar ice in both the Arctic and Antarctic, a longer-term mission than OMG’s and with hundreds of repeat flights annually that monitor the thickness of sea ice floating on the oceans, ice sheets and associated glaciers.

MacGregor, who met Guariglia in 2016, calls art “a valid idea” for reaching communities to describe NASA’s work. (Artists and news reporters are not paid by NASA to make the flights. They essentially “fly along.”) “As a scientist you’re always trying to come up with better ways to engage the audience of individuals … interested in the science and also the much larger audience of individuals who, whether they know it or not, are helping to support the work of understanding the world around us,” he says. Artists can help people better comprehend the environment and its changes — “how they think of glaciers without the scientific dressing, the nomenclature we use, the measurements we make.”

Photo by Noah Kalina

For his part, Guariglia wanted to bring the enormity of the problem home. He says, “We don’t live near Antarctica. We can’t see the ice melting. It’s happening so slow you can’t visualize it, but it’s happening so fast that we can’t ignore it.”

He chose not to ignore it and, following “my heart and my intuition,” expanded his thinking about what was possible. He sees photographs as answering questions. He wanted something more — a unique approach — and thus “hacked the printer” for his new process.

Through it all he seeks to spark emotion and compel a conversation among viewers, who sometimes aren’t even sure at first what they are seeing in the paintings.

That’s when they look closer.

Is there recognition — perhaps of an unsettling notion? Climate change as existential crisis? A moment viewers reflect on their impact on the natural world? Do they feel something?

That is Guariglia’s hope.

Photo by Justin Brice Guariglia of his own "After Nature" exhibition.

FROM WAKE FOREST TO THE ARCTIC

Justin Brice Guariglia (’97) came to Wake Forest from his hometown of Maplewood, New Jersey, as a transfer student, arriving to play baseball and major in business. An arm injury in his first few weeks scuttled the sports plan.

Baseball had meant everything to him. Without it, he had to craft a new vision for himself and a different plan for college, one he decided would have roots in his Italian heritage, which, as it happened, is part Venetian. He was accepted for a junior-year semester at the University’s Casa Artom, a palazzo in the Dorsoduro neighborhood of Venice that once served as the U.S. consulate and remains the neighbor of the Peggy Guggenheim Museum on the Grand Canal.

Venetian architecture, paintings, culture, literature and art history classes with the legendary art historian and Wake Forest lecturer Terisio Pignatti (D.F.A. ’76) exploded Guariglia’s worldview. “It opened my eyes to a whole other way to live life,” Guariglia says.

He returned to Wake Forest “a sponge,” wanting to take or audit any humanities class possible and pursue photography. Says his college friend John Hamilton (’98), a producer at Democracy Now!, “I can tell you right off the bat Justin was always really inquisitive. He wanted to turn over rocks and look underneath to see what was there. He became fascinated with photography. I could see that pretty early on, after his trip to the Wake Forest house in Venice.”

Guariglia eventually grew interested in the burgeoning scene in China. He devised a way to spend another semester abroad, this time in Beijing. He set his sights on becoming a photographer whose work would appear in National Geographic, and it took little time for him to succeed. He lived in Asia for nearly two decades before moving to Brooklyn.

Here are just a few career highlights:

+ Howard Foundation Fellow in Photography, Brown University, 2017

+ Simons Foundation Fellow, Science Sandbox @New Lab in Brooklyn, 2017

+ Author of “Planet Shanghai,” 2008

+ Best Photography Books of 2008, American Photo Magazine

+ Author of “Shaolin: Temple of Zen,” 2007

+ Repeated recognition in Pictures of the Year International competitions, Columbia, Missouri

+ “PDN’s 30: New and Emerging Photographers to Watch,” Photo District News magazine, 2000

— Maria Henson (’82)