The Art of Fixing a Shadow

By Morna E. O’Neill

PHOTOGRAPHY PERMEATES our lives; most of us carry a camera with us always (even if we refer to it as a phone) and filter our experiences through the photographic record on Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram and other social media. Why is the photographic image so enduring? And what distinguishes it from other forms of image making?

One of the best ways to answer these questions and understand the significance of photography as an art form and as a cultural practice is to start at the beginning, with its invention. As many as 14 people, including one woman, from as far away as Brazil, claimed to have “invented” photography from the mid-1830s onward. Most accounts have settled on the English country gentleman and polymath William Henry Fox Talbot as the inventor who devised the photographic negative and its positive print.

More recently, however, scholars have asked not “who?” or even “how?” but “why?” The art historian Geoffrey Batchen has suggested that the best way to answer this question is desire. After all, the apparatus of the camera — modeled on a drawing instrument known as the camera obscura — dated to the 15th century and was founded on optical principles known since ancient times. The light sensitivity of chemicals was discovered in the 13th century. A frustrated sketching trip to Italy in 1833 led Talbot to seek a new method for capturing foreign views. Talbot wished for something more: “I found that the faithless pencil had left only traces on the paper melancholy to behold.” Why did Talbot want a better record of his vacation? Or, to put it another way, why did photography emerge as a cultural imperative around 1839?

Talbot was a Cambridge-educated gentleman, one whose family fortune provided him with the time and resources to experiment with his drawing implements and his light-sensitive chemicals. He began his experiments with what he called “photogenic drawings,” which we now refer to as “photograms.” But his original formulation lends an insight into how Talbot himself thought of his experiments: photo (Greek for light) and genic (producing) drawing. These images were made without a camera by placing an object directly onto light-sensitive paper and exposing it to the light.

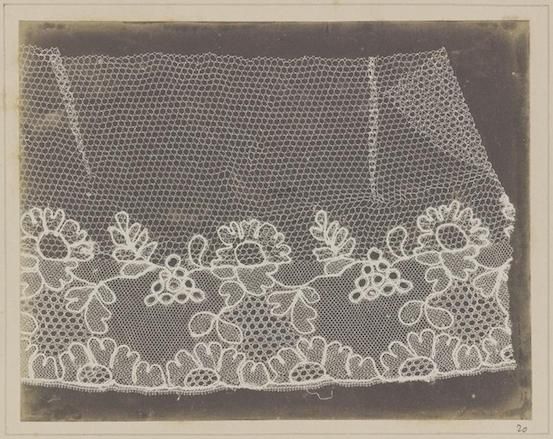

“Lace” illustrated the detail possible with this new type of image — what we think of today as a “negative” from which one could print a “positive.” Talbot placed the lace on a piece of paper coated with light-sensitive chemicals and exposed it to light: the light darkens the paper in the areas of the openwork pattern, while the parts of the paper underneath the threads remain light. Talbot could then take this fixed photogenic drawing and treat it as a negative: placing it against a second piece of light-sensitive paper, he could produce a “positive” image of the lace.

William Henry Fox Talbot, “Lace,” 1845

In the “science” of photography, Talbot often depicted traditionally feminine objects such as lace, a record perhaps of the assistance he received from his wife, Constance Talbot. For Talbot, also, lace illustrated the “accuracy” of this process: he wrote, “(U)pon one occasion, having made an image of a piece of lace on an elaborate pattern, I showed it to some persons at the distance of a few feet, with the inquiry, whether it was a good representation? When the reply was, ‘that they were not to be so easily deceived, for that it was evidently no picture, but the piece of lace itself.’ ”

Lace was a favorite subject as it allowed him to demonstrate what later theorists would call the “indexical” nature of the photographic image. That is to say, the photogram illustrates the fact that the photograph is always an “index” — what the Oxford English Dictionary describes as “an informer, a sign, an inscription.” The French philosopher Roland Barthes defined the indexical nature of the photograph as “a record of an absent presence,” akin to the fossil or the fingerprint. Whatever appears in the photogenic drawing had to be there, in contact with the light-sensitive paper. The photogenic drawing is a record of that presence: it is a sign, an inscription, an informer of the lace.

"Why is the photographic image so enduring?"

In 1841, Talbot introduced the public to a further photographic process, this time using the principles of camera to create a negative, which could then be printed as a positive. While photogenic drawing required the physical contact of lace with light-sensitive paper, this later project uses the principle of the drawing device known as camera obscura — he exposed chemically treated paper to the sun through a lens, producing an image in negative that could be transferred to another sheet of paper to produce a positive. In the confusion of light and dark, it is a technology that we recognize today.

Talbot referred to this process as “the art of fixing a shadow,” locating the origins of photography in both nature and culture. His friend and fellow experimenter, the astronomer Sir John Herschel, suggested the term “photography” or “light-writing” — an image as a result of the agency of light acting upon an object. Photography is a product of culture, the work of humankind, but one that takes advantage of the processes of nature. When contemplating any of the humble images, such as lace that inaugurated the photographic medium, Talbot and his colleagues appreciated the order, complexity and beauty, as we do today.

Morna E. O’Neill is an associate professor in the art department. She teaches courses in 18th- and 19th-century European art and the history of photography.

Books, Boxes and Photographs

By John Pickel

PHOTOGRAPHY IS A provocative medium. We are sophisticated viewers seeing innumerable images daily. Connected to the machine and mass production and with the ability to produce realistic images, many of us accept photographs as truthful documents. Others understand that photography has no greater claim to truth than any other medium. But a photograph of a loved one or deceased parent grips us, challenging this assumption. There’s an essence, a quality generated by the mechanics of photography, which creates a tension between what we know and what we feel.

While on academic leave in Berlin, Germany, and using a smartphone and a photography app, I shot Die Berliner Bahn (The Berlin Train) series with that tension in mind. The app blanks the phone screen and vibrates when each shot is taken. The wide-angle and extreme depth of field of the camera allowed me to capture candid images that a conventional camera could not. My daily practice was wearing headphones and listening to music while pointing the phone toward a subject that caught my eye.

As the screen was blank, I could not compose the photographs. Although the process might read as spontaneous and random, I consciously chose the subject matter by pointing the phone at passengers who attracted me on some level or at that which suggested motion. After shooting more than 1,000 images, I culled them down to 25 by choosing dynamic compositions that would resonate with each other. This series is my subjective representation of a few months on the Berlin mass transit system.

My interest in handmade books grew from storyboarding video projects. Many times I would shoot still photographs, placing the prints in the sequence of the storyboard.

As time passed, I found my attention to detail and the simple rewards of making a beautiful object became more important than producing a video. Now, I direct the audience through the tactile and intimate experience of viewing the handmade book.

For example, the box of books entitled “Family” was inspired after I inherited a large cardboard box of family photographs. (My mother was obsessed with photographing her family. At one point in my childhood, I counted more than 100 framed photographs just in our living room.)

"There’s an essence, a quality generated by the mechanics of photography, which creates a tension between what we know and what we feel."

After scanning the images, I printed them back-to-back on 17×22-inch inkjet paper and then tore them down to signatures for the three books. Many spreads are quite abstract, depicting little recognizable visual information. Others may show the chin of one relative, juxtaposed to an eye or part in someone’s hair. The box was made to suggest a cigar box, but using materials with the color and feel of something much more precious.

With the “Berliner Bahn” I photographed the unknown to make it more familiar. With “Family” I abstracted the familiar to create distance. This is not a simple dichotomy. I am more interested in the tension between knowing and feeling. Photography provides me with endless possibilities to explore this tension creatively.

John Pickel is associate professor of photography.