The late Wallace Carroll taught a popular First Amendment class but didn’t reveal his place in history on the global stage or as an extraordinary editor of consequence in his community of Winston-Salem. It’s time people know.

In 1977, in the spring of my junior year at Wake Forest, I was walking across the Quad when I saw one of my professors. Dressed in a Brooks Brothers shirt and cashmere sweater, he waved at me and commented on the brilliance of the sunlit afternoon. He was walking briskly, I knew, to the pool to do his daily laps and then most likely to the library, where he seemed to spend a great deal of time.

Wallace Carroll, or “Mr. Carroll” as we all called him, as far as I know wasn’t a full professor, and I wasn’t sure which department he was in. The Sam J. Ervin Jr. University Lecturer, he taught a seminar on the First Amendment, and as a journalism student I thought that might be an interesting course to take. I heard that Carroll had been the editor and publisher of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, but beyond that I knew little about him.

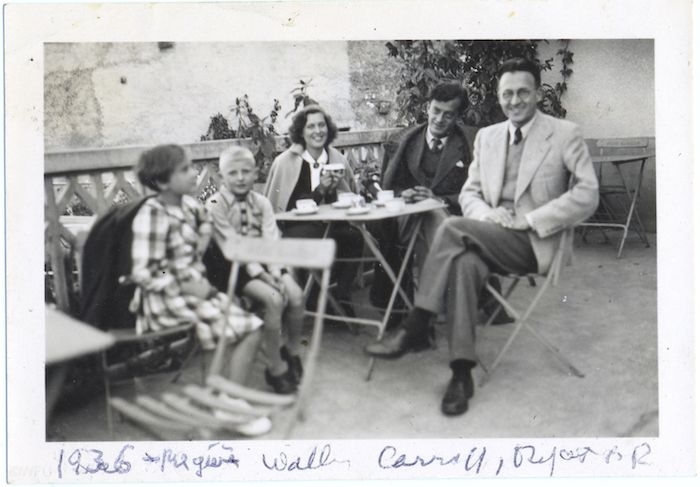

Wallace Carroll, far right, as a young correspondent for the United Press in Switzerland.

In class he was understated, calm, deliberate and kind. We read Anthony Lewis’ “Gideon’s Trumpet,” a seminal work on the constitutional right to counsel, and several Supreme Court cases. He would stand in the corner, arms folded, and ask questions about the reading. I tried to sound worldly when called upon and cringe now to think of the quality of the final paper I wrote. He marked it up and made suggestions for improvement.

“You have a good mind,” he once told me. “You just need to learn to express yourself better.”

Former students agree: You wanted to do your best for Mr. Carroll. I often wondered what he would think of my career moves as I left Wake Forest to take a job in journalism in Washington, D.C., and, in the end, if he would be proud of me. Would I measure up to his standards?

As the years went by and I left journalism to work in another field, Carroll entered my thoughts less frequently.

That changed a little over a year ago when I came across “Citizens of London: The Americans Who Stood With Britain in Its Darkest, Finest Hour,” a book by Lynne Olson. It told of three influential Americans, broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow; W. Averell Harriman, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s special envoy to Europe who later became U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union; and John Gilbert Winant, then-U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, all working to bring the United States into World War II when England stood alone in facing the Nazi juggernaut. It turns out Wallace Carroll was a friend to all three and appeared throughout the book.

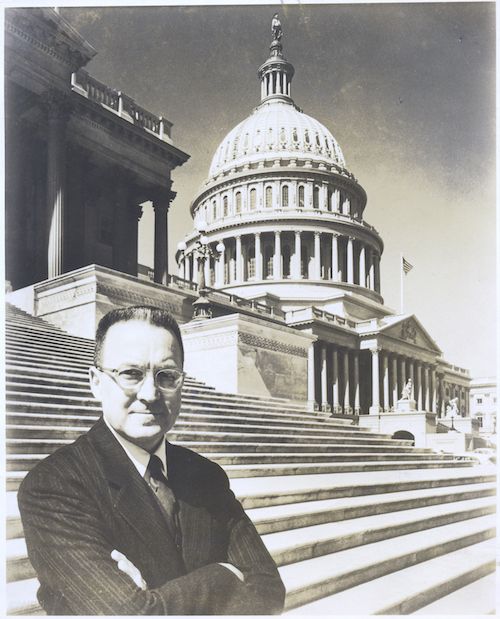

As news editor for the New York Times from 1955-1963, Carroll covered both the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations.

This surprised me. So I Googled him, and I’ve been fascinated ever since. I intend to write a book about him — he died at age 95 in 2002, and many days I find myself at the Library of Congress poring over the library’s seven boxes about his life and work.

Wallace Carroll was not just the editor and publisher of the local newspaper. He was present and reported on most of the major events of the 20th century. He knew, befriended or advised nearly all the mid-century’s key decision-makers — from Winston Churchill to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. As a correspondent for United Press he covered the League of Nations in the mid-1930s, sent dispatches on the bombing of Madrid during the Spanish Civil War, interviewed Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery following the British army’s narrow escape from Dunkirk and reported nightly from his office rooftop on the bombs falling on London during The Blitz. He was on the first convoy into the Soviet Union following the Nazi invasion in 1941 and remained to cover the Nazi’s initial assault on Moscow. Barely making it out, on his way home via Persia (now known as Iran), Singapore and the Philippines, he landed in Hawaii seven days after the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack and filed among the first reports from the field. He eventually became the first director of the U.S. Office of War Information in London, specializing in psychological warfare operations during World War II.

Carroll interviews young Royal Air Force pilots during the Battle of Britain.

Wow, I thought. Who knew? Certainly none of us who sat in his class, even though there had been a few hints: One time when discussing a paper I was writing on the Battle of Stalingrad, he casually mentioned that, yes, he had seen the Soviets fight and knew they were capable of beating the Nazis. Later, at a small party for us students, he introduced his friend, the journalist George Will, to me. And later I learned that Carroll had been Anthony Lewis’ editor at The New York Times and encouraged him to write “Gideon’s Trumpet.”

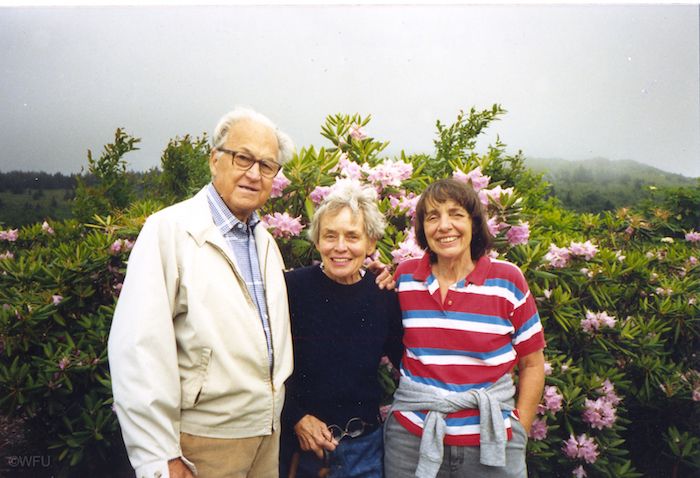

Here with his wife, Peggy, center, and Elizabeth (Lib) Jones Brantley ('44, P '72), one of the friends who joined voices to preserve the New River Valley.

After the war, Carroll worked as executive editor at the Journal and Sentinel from 1949 until 1955, when James Reston hired him to be his deputy in the Washington bureau of The New York Times to oversee day-to-day coverage. When he decided to leave his Times position in 1963, the paper offered him “the Rome bureau, or any other bureau that was open,” if he changed his mind, according to Gay Talese in his 1969 book, “The Kingdom and the Power, Behind the Scenes at The New York Times: The Institution that Influences the World.”

Instead he returned to Winston-Salem, where he would continue to make his mark on the city and beyond. During his tenure as editor and publisher of the Journal and Sentinel from 1963 to 1973, Carroll led the newspapers’ efforts in support of busing to desegregate the city’s schools, restricting gun use and persuading lawmakers to establish the North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem.

In 1968 he wrote “Vietnam — Quo Vadis?” (Vietnam — Where do we go?), a signed editorial questioning the war in Vietnam and urging the United States to get its priorities straight: “But we must see that we cannot allow Vietnam to become the be-all and end-all of our national policies. Starting with that realization we can make our way back to our true role in the world — not as destroyers but as builders, not as sowers of fear but as bringers of hope.” The editorial is widely acknowledged as influencing President Lyndon Johnson’s decision to begin disengaging from Vietnam.

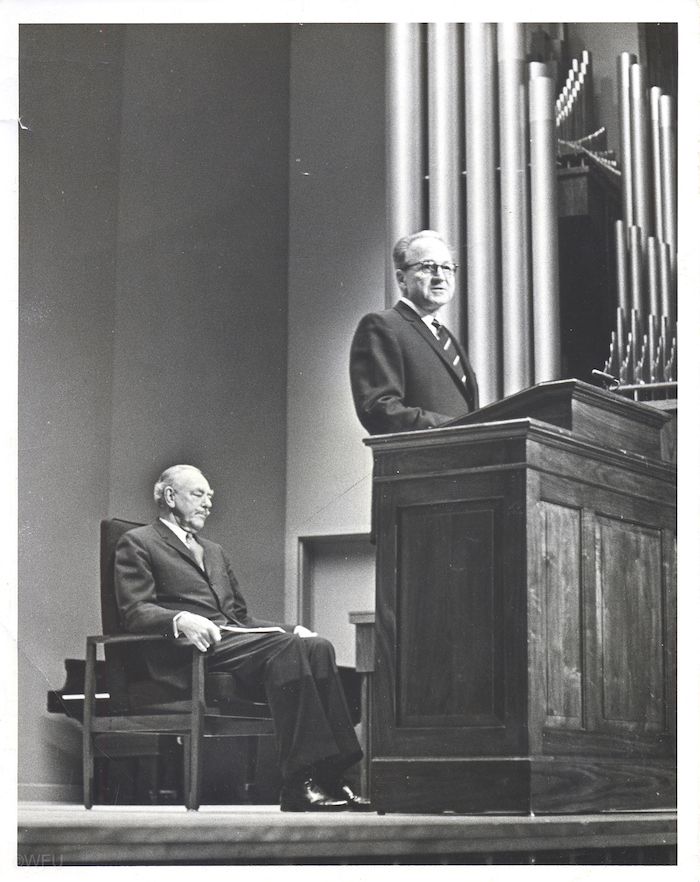

Carroll introduces his Dean Acheson, former U.S. Secretary of State.

In 1971, under Carroll’s tutelage, the Journal and Sentinel won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, for environmental reporting that ensured strip mining would be halted in thousands of acres in the mountains of northwest North Carolina and southwest Virginia.

When he retired as a newspaperman in 1973, Carroll characteristically underplayed his role, crediting the paper and its staff. “The Journal and Sentinel,” he said at the time, “had a vital influence in transforming this community from a mill village dominated by three or four very strong-willed, feudal barons to where it is today, a pretty open community.”

If we were to bring back the concept of contributing to the community — or to the well-being of the whole — we would do well to remember Carroll, the man Provost Emeritus Ed Wilson (’43) calls “the most influential editor in the South then and since.”

Former managing editor of the Winston-Salem Journal Joe Goodman, in his summary of Carroll’s career, wrote of Carroll’s importance in American journalism, international affairs and North Carolina’s cultural development. It is “because (Carroll) is content to stand in the background with arms folded that his achievements have never been summed up,” he concluded.

Perhaps, Mr. Carroll, it is time to change that.

Mary Llewellyn McNeil (’78) is a former official of the World Bank and member of the Wake Forest Board of Visitors. She lives in Washington, D.C.

The Power of Words

James Reston, the longtime editor of The New York Times, once said that Wallace Carroll could “edit the Gettysburg Address and improve upon it.” Precise and crisp in his writing, Carroll railed against hyperbole and jargon, at one point agreeing with Reston never to allow the words “unprecedented” or “universally” to appear in published articles. Many Winston-Salem Journal reporters recalled that their greatest fear was to have a blue note, written by Carroll and attached to their articles, appear on the office bulletin board pointing out grammatical errors, misplaced commas or other literary failings.

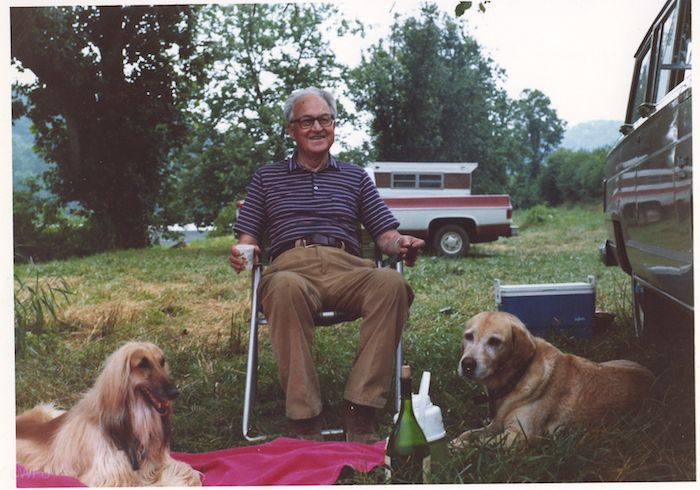

Here with his dogs at his mountain retreat near Sparta, North Carolina, where Carroll and his wife welcomed students for picnics and ice cream.

Words had to be precise, Carroll believed, because they had the power to change things. In an address at his alma mater, Marquette University, in 1969, he cited Franklin Roosevelt’s admonition, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” and Winston Churchill’s pledge to “never surrender” during World War II as examples of how words had the power to change history. “The English language has stood us in good stead,” he concluded. “Never doubt that we shall need it again in all its power and mobility.”

Carroll practiced what he preached. He used his skill with words to foster a more open and enlightened community in Winston-Salem and beyond. Perhaps among his proudest achievements was blocking the Appalachian Power Co.’s plan to dam the New River and generate electricity through a massive project stretching from Grayson County, Virginia, into Ashe and Alleghany counties in North Carolina. Carroll, drawing on his many contacts and reputation in the journalism community, managed to get more than 150 newspapers across the country to run editorials in support of the river’s conservation. As a result — and with immeasurable help from his wife, Peggy — in 1976 Congress approved legislation to place large stretches of the river valley in the Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and, on Sept. 11, 1976, President Gerald Ford (LLD ’80, P ’72) signed it into law. The Carrolls were on hand at the White House. More than 5,000 acres of land and 66 miles of stream and riverbank won protection in what remains a cherished part of the country.

Newspapers, he believed, had a moral imperative to take on this kind of work. Until his death in 2002 at age 95, Carroll considered words the tools through which this could be accomplished. “He had the journalists’ urge to further his listeners’ understanding,” said Doug Lewis at the funeral service. “It was his wonderful combination of intellect and conscience which gave Wally’s carefully reasoned and artfully worded editorials such power … he was our collective conscience at work.”

— Mary McNeil (’78)