Airports are the curse of Jason Benetti’s life. That’s an especially bad thing for someone who spends more time in the air — and on the air — than in his Chicago apartment.

It’s at airports, as he hurries to catch his next flight, that his disjointed gait attracts the most unwanted attention. Inevitably, a well-meaning airport employee in a cart will pull up beside him and offer a ride.

“I’m good, thanks,” he tells them.

When a TSA agent once offered to get him a cane, Benetti (JD ’11) resisted the urge to shout, “Yes, I want a cane. To hit you over the head!”

Had Benetti spoken up, perhaps the TSA agent might have focused on the almighty power of the Benetti voice, not the inelegance of the Benetti gait.

Benetti is the television play-by-play announcer for the Chicago White Sox. Even if you don’t live in Chicago, you’ve probably heard Benetti’s smooth baritone. He also announces college baseball, basketball and football games on ESPN. You may have done a double take if you saw Benetti announce Wake Forest’s win over Texas A&M in the Belk Bowl in December. With his glasses, his slight build and his lazy eye — or as he prefers to call it, his “curious eye” that looks off to the side even when Benetti faces someone — he does not look like the typical sports announcer. But blessed with a beautiful voice, a quick wit, a sharp mind and a gift for storytelling, Benetti has moved up from broadcasting high school football and Minor League Baseball games on the radio to television’s big leagues.

“He has pipes that most of us can only dream of having,” says Dan Bernstein, co-host of a long-running radio sports show in Chicago.

Benetti, 34, also has cerebral palsy. “CP,” as it’s often called, is a neurological disorder caused by abnormal development or damage to the brain before, during or shortly after birth. Its symptoms vary widely, but CP most often affects body movement and muscle coordination. One in three people with CP can’t walk; one in five can’t talk, according to the Cerebral Palsy Foundation. For Benetti, the only lasting signs are his unusual gait and his lazy eye.

Jason Benetti calls the Wisconsin-Purdue game for ESPN in Madison, Wisconsin, in February.

He’s overcome those challenges to achieve his boyhood goal. Growing up on the South Side of Chicago, he cheered on his beloved White Sox. When his elementary-school teacher asked students to write a paper on what they wanted to be when they grew up, Benetti already knew. Some of his classmates might have dreamed of playing for the Sox or their crosstown rivals to the north, the Cubs. Benetti wanted to be the broadcaster calling the home runs and double plays for the Sox.

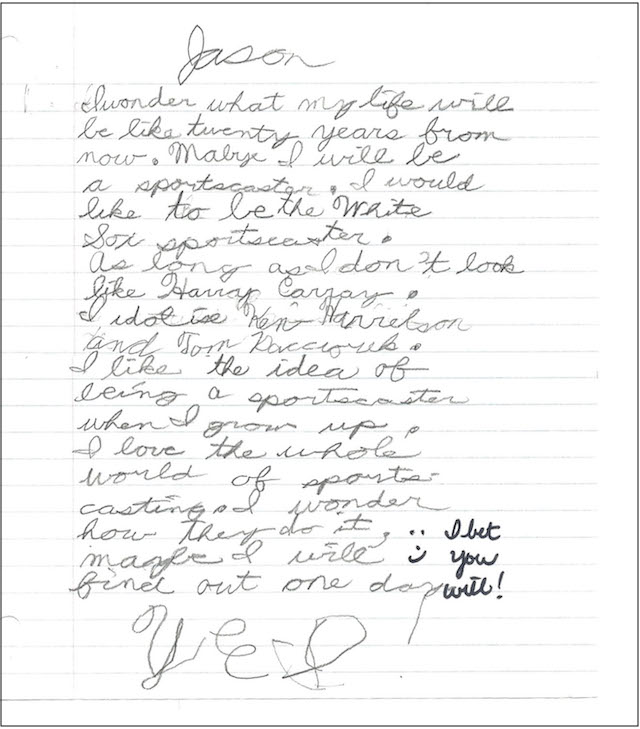

“I wonder what my life will be like 20 years from now,” a young Benetti wrote in elementary school. “I would like to be the White Sox sportscaster. As long as I don’t look like Harry Carray [sic]. I idolise [sic] Ken Harrelson. … I love the whole world of sportscasting. I wonder how they do it, maybe I will find out one day.”

His mom saved everything her only child made, including the paper immortalizing her little boy’s dream.

The little boy grew up to be named, in 2016, the successor to his boyhood idol, Harrelson, as the television play-by-play announcer for the White Sox. It’s a lofty perch also once held by Baseball Hall of Famer Harry Caray, who spent a decade with the Sox before joining the Cubs.

“The White Sox hit a home run,” Benetti’s TV partner, Steve Stone, told the Chicago Tribune when Benetti was hired.

Benetti’s law professors still think he would make a fine attorney. But instead of using his commanding voice in the courtroom, he’s using it in a different field to change the way we look at someone with a disability.

“I’m a firm believer that some people, through no fault of their own, have never encountered someone like me,” Benetti says. “It’s made me realize that someone with a disability has the opportunity to surprise people every day. You have the chance every day to change someone’s mind.

“You always hear, ‘don’t judge a book by its cover,’ and then we do.”

On a frigid February morning, Benetti enters Guaranteed Rate Field in South Chicago under a sign that reads “World Champions, 1906, 1917, 2005.” He walks at a fast clip through the White Sox front offices. “I forget that I walk differently from other people,” he says. “Then I’ll walk by a mirror, and I’m like, ‘That’s funny.’ It’s like I forget about it, which is so extravagantly impossible.”

From the TV booth, high above home plate, Benetti enjoys a magnificent view of the field. He’s been coming to this ballpark since he was a child.

His mom, Sue, was a Sox fan. His dad, Rob, began as a Cubs fan, perhaps, Benetti quips, due to a poor upbringing. (Rob has long since converted.)

The Cubs-Sox rivalry runs deep. On a basic level, it’s a north-south divide. The North Side Cubs play in venerable Wrigley Field in the middle- and upper-income Lakeview neighborhood. The Cubs are better known nationally because of their extensive television reach.

The South Side White Sox play in the more racially diverse, working-class Bridgeport neighborhood and boast among their fans former President Barack Obama. Their historic ballpark, Comiskey Park, was razed in 1991 to make way for a modern venue, which, after three name changes, is called Guaranteed Rate Field, for a residential mortgage company.

Bob Grim, senior director of business development and broadcasting for the White Sox, at right, with Jason Benetti.

Benetti is too young to remember Comiskey Park, torn down when he was only 7. But the old park is tied to his family history in the oddest of ways. His parents were walking to Comiskey for a game when a chunk of concrete fell off a building. It missed Sue, five months pregnant with Jason, but it struck Rob in the back of the head, causing severe neck and back injuries. He remained hospitalized when Jason was born six weeks later at the same hospital. (Rob eventually recovered and become an air traffic controller in nearby Aurora.)

Born 10 weeks premature, Benetti spent three months in the hospital. He survived a respiratory illness but was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, which required several surgeries. He used a wheelchair in first grade and later wore leg braces.

Otherwise, his childhood was normal, and he credits his parents. He loved sports from an early age, playing Wiffle ball and a mean game of H-O-R-S-E on the basketball court. He spent hours in his bedroom playing sports video games and watching games, with a twist. He would turn down the volume and “announce” the games, drawing on players’ names and statistics that he had memorized.

The Benettis lived close enough to the ballpark to take in Sox games regularly. He remembers once as a young boy struggling to climb to the second to last row in the upper deck. “Hey, mom and dad, maybe next time we could sit a little lower.”

What he remembers most? The smell of the park and of the food: the bratwurst, sausages and onions, and funnel cakes. And, not surprisingly, he recalls the voice of the public-address announcer, Gene Honda, still announcing today, sitting in the booth to Benetti’s right on game days.

"Jason has quickly become a 'rising star' to White Sox fans."

If he wasn’t at the games, Benetti was listening to Ed Farmer on the radio or watching Ken Harrelson on television. “Early on, I knew I liked the people who talked about sports. … It’s easy for people to say, ‘Well, he’s calling it because he couldn’t play it,’” Benetti says, quickly dispensing with that notion. “I was never calling out my name when I was a kid. I had no sports-y aspirations. Would I like to be a crossword-puzzle champion? Maybe. But no sports-y aspirations.”

In high school, Benetti played the tuba, not exactly the best choice for marching band for a slight kid who had trouble walking. A kindly band teacher came up with what he thought was the perfect solution for the band’s halftime performances at football games. He stationed Benetti at the 20-yard-line while the rest of the band marched around him, like “planets circling the sun,” is how Benetti remembers it.

When that didn’t work out, the band director had another idea. He dispatched Benetti up to the press box to announce the band’s halftime show. “Coming up next,” Benetti remembers the script, “medley from ‘Ragtime.’ ” He was soon announcing football games on the school’s radio station. He was good at it, and he loved it. He was in the game.

"I'm a firm believer that some people, through no fault of their own, have never encountered someone like me."

In person and on Twitter, Benetti is funny and engaging. He’s quick with a self-deprecating line about his disability. On his Twitter page, he’s posted a YouTube link to the classic Monty Python skit, “The Ministry of Silly Walks.” In the skit, John Cleese plays a bureaucrat at a fictional British government agency who displays an over-the-top routine of silly walking.

Shouldn’t he be offended by a skit that makes fun of how someone walks? Why? he asks, it’s hilarious. “If that (agency) existed, I would have a cushy government job,” he says, wondering why people can’t talk about CP without being easily offended. “I’m comfortable enough with me at this point to say, ‘Let’s go; bring on your funny stuff.’ ”

He didn’t always feel that way. Growing up, he seethed at slights or assumptions that a physical disability also meant a mental disability. When he went to college at Syracuse University, friends pushed him to get beyond his anger. You can’t control what people say, they advised him, but it’s your choice how you choose to react.

Now, he’s willing to give people — even those at the airport — the benefit of the doubt. Offers of help come from the goodness of people’s hearts, and he doesn’t want to discourage that. What he does ask is that people think first before making assumptions. Don’t assume that someone with CP can’t also be a law graduate and a successful sports announcer. Talk to him. How else are you going to learn what it’s like to have CP?

“At the airport, a little kid was looking at me and she said, ‘Why does he walk like that?’ And her dad says, ‘Shhh.’ First of all, I can hear. Why not just explain, ‘He walks a little differently, but he has skills that you don’t have, and you have skills that he doesn’t have.’ How would she know? I’m something that she’s never encountered before.”

“I’m a novelty, like a Slinky. Imagine a Slinky rolling down your stairs. You’re 8 years old, and there’s an alien life form coming down your stairs. I don’t know if kids have a notion of me, either. Generally, I’m the first one of me they’ve seen.”

At Syracuse, Benetti wasn’t content to major in one subject or call only one sport. He earned degrees in broadcast journalism, economics and psychology, and he broadcast lacrosse and women’s basketball games. His college demo tape captured the attention of sportscasters such as veteran ESPN announcer Sean McDonough.

“He was a network-quality play-by-play broadcaster then,” McDonough says. “I’ve listened to dozens of student tapes over the years, and his was — and still is — the best I’ve heard.”

Like the Major League players he covers for the White Sox, Benetti worked his way up from the minor leagues, calling games for teams in Syracuse, New York, and Salem, Virginia. On the radio, his inhibitions disappeared. No one could see him. No one knew that the great voice belonged to someone who had a disability.

On one of the many endless, lonely bus rides from small town to small town, he began to wonder about other careers. A friend was taking the LSAT. Benetti had always been curious and inquisitive, and even a bit argumentative, so he thought, why not go to law school?

At the time, he was announcing basketball games for High Point University and serving as an in-studio radio host for ISP Sports in downtown Winston-Salem. He wasn’t about to give up his broadcasting career. Wake Forest was convenient and, as it turned out, the perfect choice. He was upfront with his professors; he would have to miss some classes because of his schedule, but he would always be fully prepared and committed to earning his degree.

“He comes across over the air as a very articulate, quick-witted young man. What’s beneath that is hours of preparation. Kind of like a trial lawyer.”

“If you lined up 1,000 law schools, 999 would have been horrible for me, and I wouldn’t have finished,” he says. “Wake was the one place that would have worked. I will love Wake not only for the people, but for what the people did for me.”

Two of his law professors, Wilson Parker (P ’00, ’10) and Ralph Peeples, baseball fans who became some of Benetti’s biggest supporters, marvel at his ability to connect with his audience by telling stories about players. Years ago, when Benetti was the announcer for the Syracuse Chiefs minor league games, Parker and Peeples would travel to Charlotte or Durham, North Carolina, for a Chiefs game and sit with him in the radio booth.

“He comes across over the air as a very articulate, quick-witted young man. What’s beneath that is hours of preparation,” says Peeples, who pauses a minute and then adds, “Kind of like a trial lawyer.”

Jason Benetti calls the Wisconsin-Purdue game for ESPN in Madison, Wisconsin, in February with analyst Robbie Hummel.

Law school changed him in important ways, Benetti says. He learned how to relate to people, how to see both sides in an argument and how to fully prepare to present a case or announce a ballgame. “In the jury box, you could be the difference between somebody living or dying. That’s not the case generally in a sporting event — unless you’ve made a really awful wager.”

Benetti never had time to take the bar exam. His career was moving in an unexpected direction, into television. He signed with ESPN in 2011 after broadcasting high school and Minor League Baseball games on television for several years.

He speculates that he probably lost some jobs because of employers’ concerns about his disability, but he doesn’t dwell on that. When he pursued his dream job with the White Sox, it didn’t come up. “He got the job because he’s a good broadcaster, not because of the side stories,” Brooks Boyer, the White Sox senior vice president of sales and marketing, told the Chicago Tribune.

He’s already won over White Sox fans, who love his insight into players’ backgrounds and his affinity for video game challenges. “Fans have warmly accepted Benetti’s voice into their living rooms,” read a blog post on South Side Sox. “Benetti is intelligent (and) quirky” with an “engaging personality and youthful exuberance.”

Benetti didn’t set out to be a trailblazer. He scoffs at any notion that he’s something special as a person with a disability calling a professional sport. He’s just using his mind and voice. “It’s not like I’ve become the home-run king or started throwing the javelin.”

He doesn’t want to be the best sports announcer with cerebral palsy; if he does a good job, viewers and fans won’t care that he has CP. But if someone finds inspiration in what he does, he’s happy to have an impact. He’s become more comfortable speaking about CP and appears in two videos to raise awareness for the Cerebral Palsy Foundation.

If he ever has any doubts about how far he’s come, he can drive to his parents’ house in South Chicago and ask his mother for the elementary-school paper he wrote describing his dream to become the White Sox announcer. It has a smiley face from the teacher, along with her words, “I bet you will.”

Young Jason, seeing unlimited potential, wrote underneath in large letters, “Yes!”

He made an A.