WORRELL HOUSE

An alumnus returned to 36 Steele’s Road in London to examine ‘a fixed point from which to measure distance.’

By Ed Southern (’94)

Oh, no, that was not strange at all, climbing Haverstock Hill again, graying now and gimpy-kneed, 24 years since I climbed it every day.

Then the shorter, heavier climb, up the 14 brick-and-tile steps at 36 Steele’s Road: that wasn’t strange at all, either.

Ringing the bell at Worrell House’s front door, realizing that the last time I had to ring this bell was the very first time I came to this house? Realizing that the last time this door opened to me, I had my own key?

Realizing, and accepting, that I have lived more years since I lived at Worrell House than I had lived before that semester, that marker from which I measure the rest of my life?

No, none of this was strange, not at all, not at all.

***

Ed Southern ('94)

I went to London in 2018 because I came to London in 1994. I know that sounds very Zen, if you’re feeling charitable, or very trite, if you’re not.

My point, though, is that I would not be where I am now had I not been at Worrell House then, that whatever roads I’ve followed since all lead back to 36 Steele’s Road.

That, too, sounds trite, reductive and obvious, but my point — in part — is that I would not recognize it as such without that spring in London, and for me, such recognitions have made all the difference.

The point I am groping towards lies somewhere deeper than career paths and cherished memories, funny stories and loyal friends, the potter’s hands of beloved professors and enriching experiences.

My point has to do with ways of being in this world, whatever corner of it you choose or stumble into.

***

The rub of being provincial is that you probably don’t know you are. Shoot, I watched CNN and read the daily paper. I aced all my AP exams. I got into Wake Forest. I’d even seen a couple of foreign films. I knew a thing or two.

I know I’m not the only Demon Deacon whose Worrell House semester was not just his first experience abroad, but his first of metropolitan life. Riding the Northern line or the 168 bus to see a play, listening to the polyglot along the way, learning to read a timetable in the first place — all were as much a part of my education as the play itself, as any book I read or lecture I heard in the Hixson library.

I imagine I’m far from the only Deacon whose semester abroad felt like a culmination, the aim not just of my college years but of all my learning up to that point, an elevated stage on which to put to the test all the facts and theories I’d learned in class. I felt as if walking along the Strand or the South Bank was the reason for every #2 pencil I’d sharpened, every bubble I’d filled in. I felt, counterfactually, that I had buckled down my sophomore year just so I’d be picked as one of the 16 for Spring ’94; and so that when I saw the Tower of London or King’s Cross I would have some dim appreciation of the bursting, grasping, imperial force behind them; and so that Marlowe’s “Tamburlaine the Great” or Stoppard’s “Travesties” or Brecht’s “Galileo” would be more to me than spectacles; and so that when we were invited to tea or a sherry party I wouldn’t appear a complete yokel.

***

I went back to London last spring to research a novel I am writing, one of whose characters comes to London to search for a missing book.

I am writing this particular novel because I have spent all but one of the years since I left Worrell House working in the book trade.

I work in the book trade because, having reached a crossroads a year after graduating, I had to ask myself what work might make me truly happy, and I remembered the joy with which I had scoured the bookshops of London, from antiquarian stalls in Camden Market to the multi-story Foyles’ flagship on Charing Cross Road.

A friend in Wake Forest’s Center for Global Programs and Studies connected me with the current house manager, Fiona Trier, who answered my ringing of the doorbell and, graciously, let me take a look around. Later one of my Spring ’94 roommates asked me by email if the house still “feels the same,” and I didn’t know how to answer. Worrell House still looked much the same, within reason, as best as I could tell: the same warm carpet on the first floor, rich as roast beef or . . . well, red ruddy Rhenish, filled up to the brim; the same dark, very English, oaken furniture in the study overlooking the street; even the same arrangement of beds and dressers and desks in our old room, #3. The library has long since lost the three lumbering PCs on which we typed our term papers and even the occasional mystifying “electronic mail” to our friends back in the States.

And while I’ve tried hard in my 40s to avoid the “kids these days” gripes of the unrepentant fogey, I have to note that in the room where we had a pay phone, there now are two washing machines and a dryer.

Kids these days.

At the end of Steele’s Road, the Load of Hay Tavern is closed, and is in the process of becoming something called the Belrose, whose name and font implies an upscale eatery. The Sir Richard Steele pub is covered in scaffolding and closed, as well, but whether for good or for renovation, I don’t know and don’t quite have the heart to find out.

Beyond that, I can’t be sure if what strikes me as different is different in fact or just different from how I remember, as shaded and haphazard as that may be. I can’t say if Worrell House still feels the same, because I do not feel the same, not at all, and not just because my left knee now predicts the weather. I have to work hard to remember the person I was then, which is a mercy. I do not know if I could bear to remember all the many things I had wrong, or any of the few things I had right, but have since forgotten.

***

I stayed out too late in Camden Town and took communion in Westminster Abbey. I sat spellbound in the Everyman Cinema and was swept along with the surging crowds through Leicester Square. I crossed Hampstead Heath on our way to the Spaniards Inn and crossed Haverstock Hill on our way to the launderette.

Pick the metaphor you prefer, because I can’t seem to: the hinge on which a heavy door hung; the axis pole where my trajectory spun and sped up like a stone from a sling; a telescope that showed what was hidden and made clear what was dim, close and far away at once and ever after; a fork in the road; a finishing school; a fixed point from which to measure distance.

In London that spring I began to figure out that education is less about knowing than understanding, and that understanding is less about mastery than approach, less about the answers than about moving through the world with a critical eye and a generous mind.

Ed Southern (’94) grew up on the edges of Winston-Salem; Wilson, North Carolina; Greenville, South Carolina; and Charlotte. He now lives again in suburban Winston-Salem, but he spends most of his free time downtown. Since 2008 he has been the executive director of the North Carolina Writers’ Network. He is the author of three books.

DORSODURO 699

Circa 1980s or 1990s, walk back in time through the neighborhood that once surrounded Casa Artom in Venice

By Joy Goodwin (’95)

All’Accademia

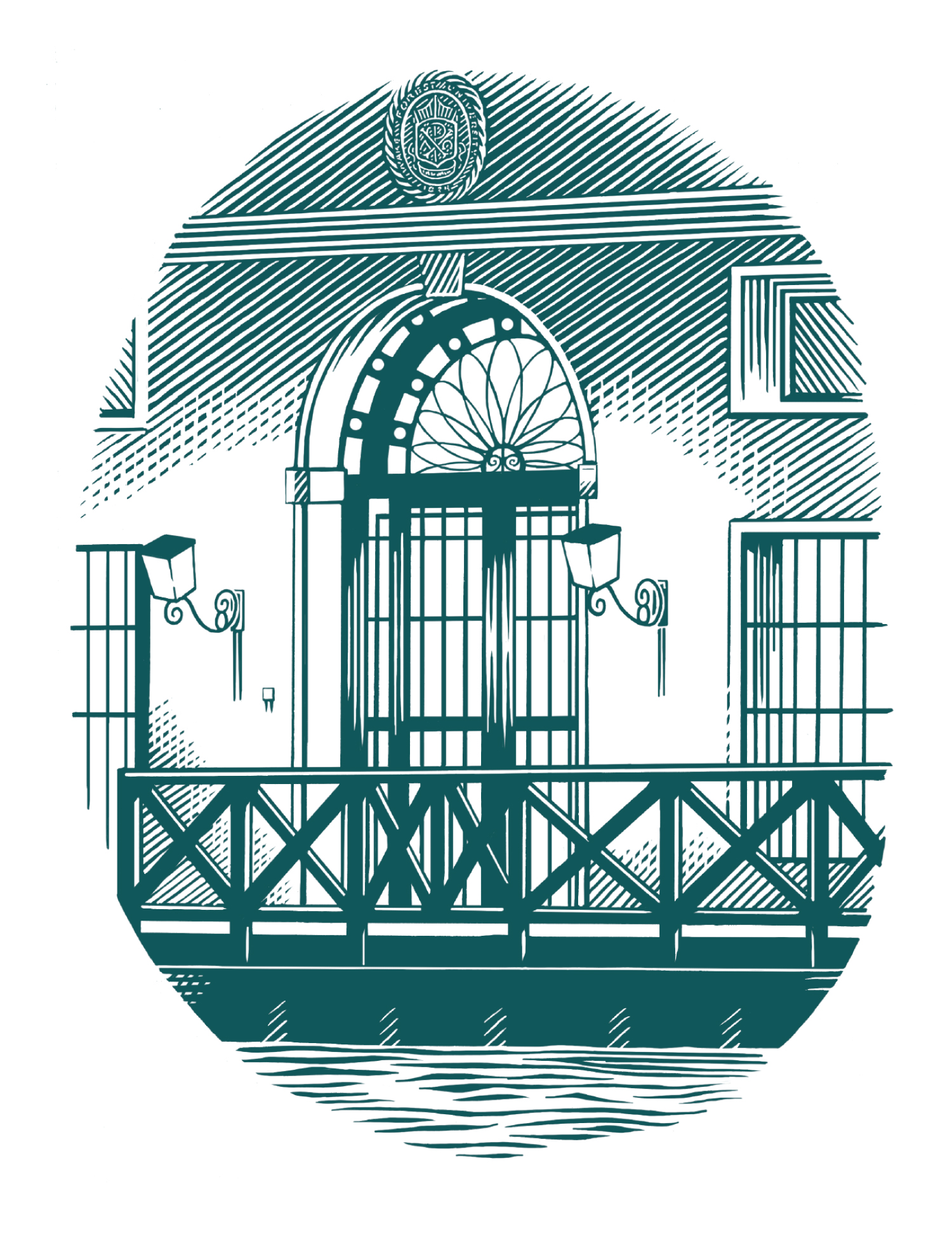

You pull the heavy door shut behind you. Your footfall echoes in the narrow calle: Close your eyes, and it might be the 16th century.

It’s shady here, till the calle jogs left past the Peggy Guggenheim Museum and deposits you — squinting — on the bright fondamenta, where you can see the sky again.

Sun glints off the little canal coursing between two stone streets. Mauro stands at his easel, adding some flying gondolas to his latest painting. “Ciao, my friend! Ciao, ciao!” he cries. He wants to talk about art, but right now you have to go: The shops are about to close for lunch, and then they’ll be shut tight for two hours, maybe three. You have, by now, developed a healthy fear of the orario.

***

You pass the cheesemonger’s and the little bridge to the restaurant Ai Gondolieri. With a name like that you were sure it was a tourist trap, but at night, off-duty gondoliers hang out in front. You enter the greengrocer’s, the fruttivendolo. In here customers are strictly forbidden to touch the fruits or vegetables, which are personally selected every morning at dawn by the proprietor, Bruno. You ask for plums. Bruno says the plums are no good today. He instead counsels pears, which he handpicks for you. The pears are exquisite, and expensive.

You pass the Corner Pub, where Andrea serves a fortifying lunch of prosciutto-and-cheese toast, aranciata (orange soda) and life philosophy. The calle again narrows, and you are packed into a dim corridor, no more than two people abreast: You wouldn’t want to get stuck behind a guy with a wheelbarrow here. You arrive at the panificio, which means bakery but sounds like the bread office. “Dimmi,” the overworked signora says, casting an accusatory look your way. (Quick: Have you touched anything? Smudged the glass display case? Cut in front of a Venetian? Forgotten the receipt?) You leave with 200 grams of bread and make sure to take the receipt.

Joy Goodwin ('95)

Outside the panificio, by the English Church, the calle ends in a wide stone plaza. Ah, that Venetian luxury: elbow room. Campo San Vio has an old Venetian wellhead, park benches and a dark green newsstand flanked by orange phone booths. On one side you see the Grand Canal; on the other, the pretty window boxes of the Hotel American. (Geraniums, the locals insist, deter mosquitoes. If you lack geraniums you’ll be advised to buy small Italian contraptions that plug into the wall and release anti-mosquito fumes.)

If it were evening you might turn left for the Gelateria Nico, or the Taverna San Trovaso, where the waiters have become your friends. But now you continue straight down a wider street — a rio terà, a filled-in canal. The hardware store is next, then the Bar da Gino, with its gleaming shelves and its soccer flags flying. Gino stands behind the marble counter, pulling perfect espresso. In the mornings you sometimes take a cappuccino and an apricot croissant here, standing among the throngs at the bar — then pay your chit, feeling very Italian.

Coming out of Gino’s you hear the lowing sound of a vaporetto either docking or undocking. You sprint to the Accademia Bridge to catch it, but you’re too late.

Your class has been frequenting the Accademia Gallery with Terisio Pignatti, a renowned art historian and an ardent defender of Venice. He decries the mass tourism that is steadily destroying ordinary Venetian life and turning the city into a theme park. He shows you the Accademia’s treasures, especially its religious paintings, a surprising number of which contain “little doggies.” He also shows you works shrouded in mystery, like Giorgione’s portrait of an elderly woman dressed in rags. She stares you right in the eye while her hand unfurls a strange little banner. The banner reads col tempo — “with time.”

A notice outside the Accademia declares that some portion will be in restauro (under restoration) for three years. In restauro is ubiquitous here. It was one of the first crucial bits of Italian you learned, along with sciopero (strike), acqu’alta (flood) and permesso (“step aside”).

Your vaporetto arrives. A marinaio in a blue shirt unfurls his rope, tosses it and slides the gate open. You nudge your way onto the overcrowded boat. “Permesso…”

On the water

Most cities in the world exist between green grass and blue sky. Venice was built between two blues.

The vaporetto, being a bus, normally just lurches from stop to stop. But occasionally it will hit a stretch of open water. Then it gains speed, and for a few giddy moments it’s a seagoing vessel, mist spraying the windows and the passengers on deck.

The other ways to go fast on the water are by water taxi, which is too expensive, or in a Venetian friend’s motorboat, playing the radio too loud under other people’s windows.

As a resident of Venice you view gondola rides with skepticism and gondoliers with respect. Sometimes, rather than walking an extra half-hour to cross the Grand Canal via bridge, you’ll take a traghetto, a kind of gondola-ferry. You drop a coin in a gondolier’s palm and step into the black-lacquered boat. Then the two gondoliers enter the fray of the Grand Canal, dodging motorboats and vaporetti to reach the opposite bank.

In the traghetto, looking down at water you have been warned never, ever, to touch, you suddenly think how preposterous the whole thing is: a city built on water, the feats of plumbing and engineering required to sustain it. There are buildings in Venice whose original ground floor has been submerged over the centuries. Now their tenants enter on the second floor.

A night walk to Piazza San Marco

Invariably, after a few hours of studying, one of your classmates will propose a walk to San Marco.

Someone slams the door shut behind you. Your voices echo in the calle. The route is second nature by now: cross the Accademia Bridge, enter Campo Santo Stefano, look for the neon green cross above the farmacia. Follow the sign tiled into the pavement to the American Express office. Then straight on to the Piazza.

There are many squares in Venice, but only San Marco is given the honorific piazza. And no matter how often you step out from under its arcades into the piazza, it gets you every time.

You are hemmed in on three sides by luminous white buildings. They flicker under the spotlights in a way that somehow renders the whole piazza a stage. On the far side the Basilica of St. Mark rises, in all its Byzantine splendor.

Two live orchestras are playing, but the square is so vast that you seldom hear more than one at a time. There are hundreds of café tables and thousands of pigeons. But just around the corner is the calmer piazzetta, and somehow this is where you always wind up, gazing across the water to San Giorgio Maggiore. The stage set of San Marco lies behind you, the black waves before you, and the moon hangs over the sea.

A casa

You step inside and yank the door shut. You’re standing in a long, high-ceilinged corridor. On your right is the laundry, a cavernous room where sheets are drying to a starchy crisp. Luciana and Marisa, the housekeepers, poke their heads out. “Ciao, tesoro,” Luciana says — hello, darling.

Luciana, Marisa and Tullio (the handyman) have worked at Casa Artom for a very long time, and they have proprietary feelings toward the house. They are well aware of the damage that students can cause and, moreover, the many weeks it may take for a repairman to arrive in Venice with the right parts or tools to fix whatever’s broken.

The corridor’s lined with bedrooms and classrooms. It ends in a gated dock with its own doorbell, where the occasional water taxi arrives. Also on this level is a vine-draped patio, where the Americans have installed a basketball hoop. The Venetians do not approve.

The library perches just above the Grand Canal. If you read a book on its green sofa, the sounds will seep into the experience somehow — the slosh of a boat’s wake, the voices calling to one another across the water: Ciao, ciao. …

At the top of the white staircase is a living room on the Grand Canal, replete with grand piano, flower boxes in the windows and tremendous views. Crossing the hallway, you pass the telephone with a little odometer that clicks as you talk. After each phone call, you must tally and pay for your clicks. Next is the dining room and then the green-and-chrome kitchen, where student cooks do violence to Italian ingredients.

Upstairs are more bedrooms; like the ones downstairs, they give onto a canal. At night, before sleep, you hear two gondoliers talking under your window. Their voices fade away, leaving nothing but the undercurrent of Venice, so constant you scarcely hear it any more. Wave upon wave, lapping endlessly at the stones. Col tempo.

Joy Goodwin (’95) is a writer and filmmaker. Her work has appeared in The New York Times and The New Yorker, among others. She teaches filmmaking at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem.

THE YELLOW HOUSE

A semester at Flow House in Vienna led to a young woman’s discovery that Europe is anything but ‘a living museum.’

By Victoria Hill (’12)

When I applied to study at Flow House, I had never left the country before. I was 19 and so desperate to travel and see the world that I didn’t much care where I went as long as it was somewhere. Vienna was as good an option as any: I had taken German in high school, and the political science department (my major) was running the spring semester.

Some classmates scoffed at my choice, saying Europe was a “living museum” and too dull to yield any really worthwhile insights. I didn’t mind. I expected it to be a practical choice, one that would let me have an adventure while staying on track with my credits.

I got so much more than I expected.

I spent all of winter break before I left looking up pictures of the house on Google maps. By the time I finally arrived in January 2010, I could conjure it flawlessly in my mind: a large, pale yellow house with a gently scalloped roof, ringed by a wrought-iron fence, and full of large windows. It felt unreal, finally getting to walk through the doors, realizing I was going to live here now. It took me slightly longer to discover that the radiator wasn’t working in my bedroom, though in my defense, I had this romantic idea that century-old houses were supposed to be drafty. In the meantime, I bought a hot water bottle and some school supplies to get ready for our classes.

I took “The Politics of Identity in Central Europe” and “Intro to Political Theory” with Michaelle Browers, professor of politics and international affairs. It was different from my political science coursework up until then; in addition to the usual journal articles, book chapters and theoretical frameworks, she had us reading literature and watching films to better understand the region. It was intellectually rich, but what surprised me most was how much fun I was having. I had only just declared my major in political science, and I’d been worried that my coursework would be the intellectual equivalent of plain oatmeal: good for you but boring. Instead, I was wearing a fake beard and pretending to be the Czech statesman and dissident dramatist Václav Havel, acting as prosecutor in the trial of Karl Marx, in a skit we performed for a final exam.

Victoria Hill ('12)

Outside of classes, my housemates and I got to know each other. I hadn’t met most of them before we arrived, but we quickly became close friends, mostly over meals: “Taco Nights,” where two of the girls taught the rest of us to play canasta, and occasions to make schnitzel any time we had guests. We would cook and talk about what had gone comically wrong for us that day. This included the time I spent 15 minutes trying to explain Crisco to the assistant at the grocery store until she got frustrated with me and yelled, “Just use butter!”

All too soon, the semester was over. As glad as I was to be back on campus in the fall, I felt homesick for Vienna. I told a lot of stories about studying abroad … and then worried about being the sort of person who told too many stories about studying abroad.

In part to distract myself, I took a class in the Experimental College with associate dean Tom Phillips (’74, MA ’78, P ’06): Beginner Contract Bridge. Over chocolate-covered almonds and bidding rules, he found out how much I’d loved my semester abroad and suggested I come by his office to talk about what I wanted to do after college. Then, Phillips, who also directs the Wake Forest Scholars Program, mentioned the prospect of applying for a Fulbright.

At this point, I was pretty sure he was nuts. I was convinced I didn’t have what it took to be selected and that any admissions committee would see right through me. Still, the thought that I might get to go back meant I would be crazy not to apply, so I worked on my applications all during the fall of my senior year.

By April, I received the verdict: I’d be going back to Vienna in the fall to study at the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna. I spent another year improving my German, studying politics and eating cheese-filled sausages from my favorite Würstlstand near the subway station. When it was over, I returned to Wake Forest once again — this time as an admissions counselor for a few years.

It’s now been eight years since I first went to Vienna, and there have been big changes in the world. In Europe, the rising number of refugees from Africa and the Middle East has generated a range of responses, including a rising tide of xenophobic politics and populism. Far from being a living museum, Vienna remains a dynamic city where people are grappling with questions of identity and belonging, just as they did when it was the heart of a bustling, multi-ethnic empire. In many ways, these challenges reflect the conversations I’ve had with my friends and neighbors back in the United States, where we are also trying to figure out the best ways for people of different ethnicities, religions, languages and customs to live side by side.

I can see how much my time at Flow House changed me as well. It shaped my career. A U.S. diplomat I met during my semester abroad inspired me to apply for a Rangel Fellowship, a program that trains graduate students who then join the Foreign Service. In joining the State Department, I feel I will be able to live out the ideals of Pro Humanitate more fully in service to my country, representing the United States to people who may know as much about my home country as I knew about Austria before I arrived. It also helps that I will get to travel the world, a passion sparked by my semester abroad. My graduate work focuses on Central Europe and questions of identity, just like in my class with Browers; as she did, I try to include art and literature in my research.

In his book “Embers,” the Hungarian author Sándor Márai writes, “Vienna wasn’t just a city, it was a tone that either one carries forever in one’s soul or one does not.” Ever since that cold January afternoon when I pulled up outside the gates of Flow House, that tone has resonated through my own life. I can hear it in the choices I’ve made for my career, in the friendships I made with my housemates and in choosing that most Viennese of afternoon study breaks: a slice of cake and a fine cup of coffee. I didn’t know what a clear pole star Vienna would be when I first decided to go there, but ever since, I have been so glad I went anyway.

Victoria Hill (’12) is a 2016 Charles B. Rangel Graduate International Affairs Fellow and the 2018 recipient of the Louis W. Goodman Award for Excellence in Comparative and Regional Studies at American University School of International Service. She is a member of the U.S. Foreign Service.