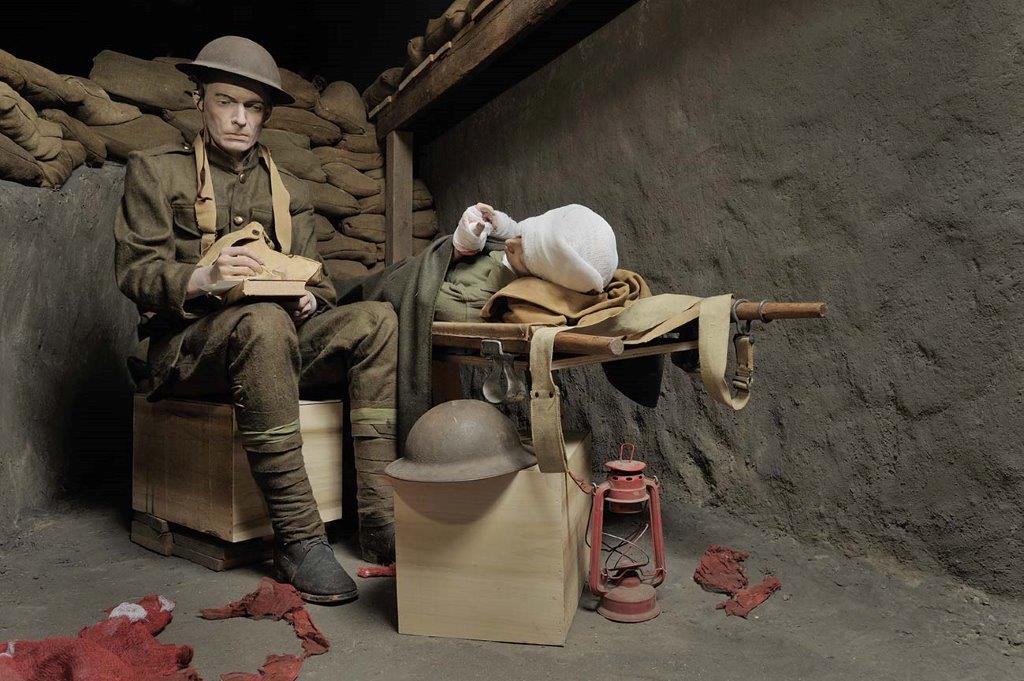

Field hospital in the "North Carolina & World War I" exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh.

North Carolina veterans of World War I didn’t want to talk to Jackson Marshall III (’80, MA ’85) about lungs burned by poison gas, flesh torn by bullets and other horrors inflicted in the muddy trenches and battlefields of Europe. The memories were too painful, even for Marshall’s namesake grandfather.

But Marshall persuaded his beloved Papa Jack — and eventually other World War I veterans — to tell him the stories that many wives and children had never heard.

In the 1980s, Marshall asked veterans of this global conflict what they wanted him to share with the world. They said they didn’t want to be forgotten.

Marshall has been good to his word.

He gathered enough material for his master’s thesis in history at Wake Forest, for a book and for the current World War I centennial exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of History, where he is deputy director and lead curator of the exhibit.

More than 470,000 visitors have seen “North Carolina & World War I,” which began in 2017 and continues in Raleigh through May 28, 2019. The museum says the immersive exhibit has broken all its attendance records for temporary exhibits and is the largest World War I centennial exhibition in any state museum in the United States. It features 500 artifacts, including a trench diorama built a decade ago by Marshall and his two sons.

Visitors walk through the trenches and see a field hospital, a poison gas area and a no man’s land, walking directly toward the sounds and lights of a German machine gun shooting at them. Then they walk behind German lines. The museum has actual war footage and film with actors portraying soldiers telling their stories.

Marshall, who recently received the Governor’s Award for Outstanding State Government Service, will retire in two months after 31 years at the museum. He will continue teaching history at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary on the original Wake Forest campus.

As Veterans Day approached, Wake Forest Magazine talked to Marshall about his work on World War I history. The conversation has been condensed and edited.

Jackson Marshall and his two sons spent several months working together about a decade ago to build this "War Game" diorama depicting World War I. One of his sons got the history bug that bit his father and is studying in the graduate history program at the University of North Carolina - Greensboro.

How did you come to the story of World War I?

I spent a lot of time with my grandfather, and in the summers my parents would send me to the farm (near Winston-Salem) for about two weeks, but I had a lot of other time with him, as well, on weekends and such. He was my best buddy to hang out with.

And I discovered his uniform in the closet, and he had a gas mask in a pantry that was off the back porch. He had tattoos. He didn’t have a limp, but he wore the heel on one of his boots strangely — all these curiosities. So I started asking him questions … and he really didn’t want to talk to me about World War I. He generally evaded my questions and would change the subject.

But over the years he began to tell me a little bit about the war, and as it turned out he was a 1917 volunteer with one of his brothers. He was wounded in a battle late in the war on Oct. 2, 1918. He was hit by German shell fire, and that actually may have saved his life because it got him out of the battle.

What was the battle?

It was the battle of Mont Blanc (also known as Blanc Mont Ridge). … He would go forward in with the infantry (in the 2nd Division), then call back in range fire for the artillery. And, of course, the Germans were shooting back with their artillery, and that’s what got him (shell fire in the leg). He was in five battles. That was his last battle. He spent the last month of the war in the hospital, and then got out and was in the Army during the occupation in Germany. So from December of 1917 until he got home in 1919, he had the full range of experiences in World War I.

What I did not know until after he died, because family members talked to me, was that he had suffered from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). He had extreme nightmares and tremors, and the family was very concerned for about two years after the war. Of course, here I am trying to pull information out of him and take him back to that nightmare. So it is amazing that he did, in fact, talk to me ultimately.

But I found that pattern with other World War I veterans. It just was a bad experience for them. I would have wives and children hovering around the doorway, and they would just have eyes as big as saucers. And they would tell me after the interview, “I’ve been married to him for 60 years, and he’s never, ever told me anything about the war and certainly has never told me anything about those stories.”

The exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of History includes more than 500 artifacts, many donated by families of World War I veterans. The exhibit includes the gas mask and uniform of Marshall Jackson's namesake grandfather.

Why do you think they were so hesitant to talk about it?

Part of it had to do with just feeling like they had failed. I think they commiserated a little bit with the Vietnam veterans. … They were welcomed home, but President (Woodrow) Wilson promised them that if they served and sacrificed, that would be the war to end all wars. And they believed that. They were that idealistic. Then they lived through the Depression, and then World War II broke out, and they ended up sending their sons into World War II and Korea and grandsons into Vietnam. It was like, “OK, we didn’t end it. There’s no end to war.”

It’s interesting that World War II veterans seem to feel more a sense of clear victory. Is that the case?

Over 80 percent of the (U.S.) population before World War I and World War II did not want to get involved. But (the Japanese attack on) Pearl Harbor made us so angry that we went in angry and with a clear cause (in World War II). We won decisive victories against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. They went through horrific experiences as well, but the survivors came back with a feeling that they had done what was necessary. Whereas World War I, they came back deflated, ultimately, about what they didn’t accomplish.

What prompted you to start talking to other World War I veterans?

My grandfather passed away in January of 1980. I finished up my senior year, took six months off and then came back into graduate school. I had had a lot of interest in the American Civil War and thought, “Well, everybody’s writing about the American Civil War. I need to do something different.” And he came back into mind because he hadn’t been gone that long. I thought, “I need to find more (World War I) veterans and talk to them because they have been forgotten.”

This is before the internet. This was word-of-mouth, going to churches and meeting people. It was very difficult to find them back in that day. But I slowly began to find more and more, the few that were still around. I would call them up and again, same routine, “No, I don’t really want to talk.” And I’d have to win them over, tell them, “I’m a graduate student at Wake Forest. I need your help. My grandfather was in the war.” They would reluctantly agree. And all of that’s really the basis of the book (“Memories of World War I: North Carolina Doughboys on the Western Front”), which is really spun from my graduate thesis. Dr. Zuber (the late Richard L. Zuber, P ’82, ’89) was my graduate adviser and was incredibly supportive.

What’s a surprising or memorable story you heard?

There are so many of them. Isaac Winfrey told me his story of his one day in combat on Aug. 31, 1918, in Belgium. He went out on patrol. Most of his unit was shot down by German sniper fire, and he saw them drop one by one, including fellas from around Winston Salem, people he knew. In fact, two of them were killed. And he survived that patrol, went back to the trenches with one of the other survivors, and then the two of them were hit by German shell fire, and his friend was killed, and Winfrey lost his arm. The family’s still in Forsyth County. They actually donated (to the exhibit) the first prosthetic arm that was issued to him from (what was then) Walter Reed (General) Hospital in 1919.

Even after the war his story was inspiring. His letter home to his mother after he was wounded, which is kind of a rambling, easy, gentle letter, at the very end … it’s almost like a postscript: “I’ve been badly injured and I’m out of the war and I’ve lost an arm and I’m coming home soon.” Then after the war he just picked up and just kept farming, and he just lived his life, got married, had a family.

Why do you think this exhibit has been so popular?

We’re hitting the Armistice Day, the 100th anniversary (Nov. 11). A number of other museums spruced up their World War I area, but they didn’t really expand it. They’re mostly commemorating the war with programming. We ended up being practically the only state museum to do any kind of … centennial exhibition. And it’s 6,500 square feet. It’s at least twice the size that most museums would do.

So that was a major commitment on our part. And I credit (museum director) Ken Howard (JD ’82, P ’15), others and the staff for supporting this. Very happily, teachers are taking their students through this exhibition by the thousands. And they’ve asked that we put all of our information online for distance learning.

See a video about the World War I exhibit, introduced by Ken Howard (JD ’82, P ’15), director of the North Carolina Museum of History.