Three centuries after the notorious pirate Blackbeard’s flagship sank off the North Carolina coast, Mark Wilde-Ramsing (’74) is uncovering the mysteries of life aboard the most-feared pirate ship that stalked the waters of the Atlantic and Caribbean in the 18th century.

Wilde-Ramsing, a retired deputy state archeologist, directed North Carolina’s efforts to recover and preserve artifacts from Blackbeard’s flagship, Queen Anne’s Revenge (QAR), from its discovery in Beaufort Inlet in 1996 until he retired in 2012.

“There are few shipwrecks from that era, and fewer shipwrecks that belonged to pirates, and only one that belonged to Blackbeard,” said Wilde-Ramsing, who lives in Wilmington, North Carolina.

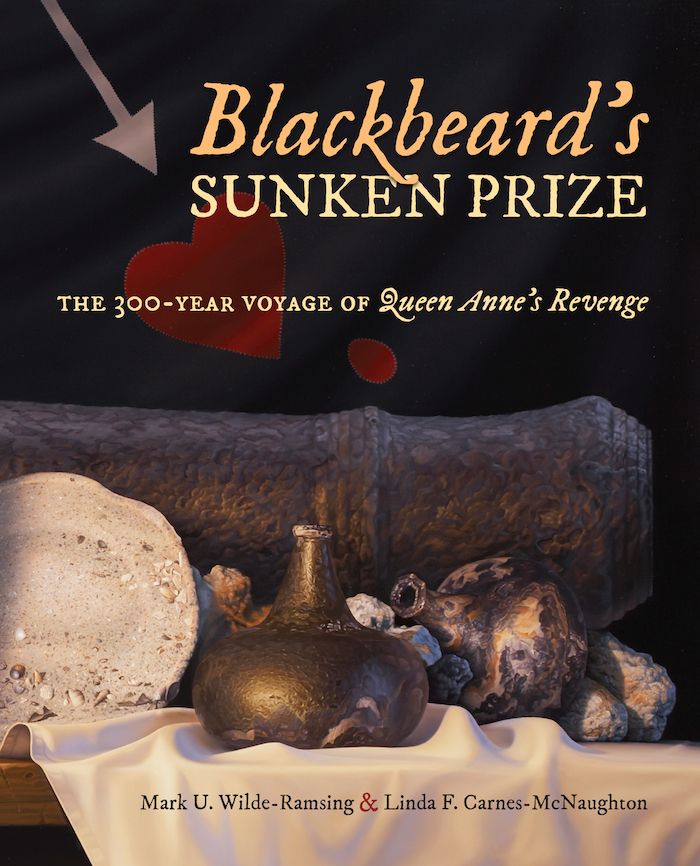

Book cover and main image above feature "Under the Black Flag," by Jack Saylor (2007), oil on linen.

He’s shedding new light on the ship and its fearsome captain in “Blackbeard’s Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne’s Revenge” (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). The book was co-authored by Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton, program archaeologist and curator at Fort Bragg’s Cultural Resources Management Program; she played a leading role in preserving and interpreting artifacts recovered from the shipwreck.

The 100-foot, three-masted wooden ship itself had largely deteriorated by the time the ship’s remains were discovered just two dozen feet below the surface of the Beaufort Inlet. An underwater archeologist, Wilde-Ramsing made hundreds of dives to the ship, in addition to directing work on land to preserve and interpret recovered artifacts.

About 60 percent of the site has been excavated. Hundreds of artifacts have been recovered from the ocean floor, and many are on display at museums in North Carolina. “Full scale recovery of the vessel from the seafloor … when successfully completed, will place it among the world’s most important wooden shipwreck recoveries,” Wilde-Ramsing and Carnes-McNaughton write.

Mark Wilde-Ramsing, retired project director of the recovery of Queen Anne's Revenge shipwreck.

Although he didn’t discover any lost caches of gold or pieces of eight, Wilde-Ramsing and his team found treasures of a different sort: everyday items such as buttons, pottery and glassware to larger items such as cannons and anchors weighing over a ton, all offering a fascinating peek into Blackbeard’s world.

The artifacts are a time capsule that tell the story of life on the ship, Wilde-Ramsing and Carnes-McNaughton write, such as what the pirates ate, how they dressed, the arms they carried and the primitive medical instruments on board.

Every artifact was fascinating, Wilde-Ramsing said, “knowing that I was the first person to see these things since those pirates were running around on deck.”

QAR ship's bell, dated 1705. (Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

For someone who spent half of his career exploring underwater remains of the QAR, World War II patrol boats and Civil War blockade runners, it seems fitting that Wilde-Ramsing grew up on the coast. But he grew up on the California coast, in San Diego where his dad was stationed in the U.S. Navy before his family moved to Alexandria, Virginia. Mark Ramsing, as he was known then, came to Wake Forest thinking he might become a veterinarian.

That changed when his anthropology professor, Ned Woodall (P ’99), encouraged him to join a field exploration of 1,000-year-old Pueblo Indian ruins near Taos, New Mexico. He fell in love with archeology and a fellow student named Dina Wilde. “I’ve always been fascinated by people’s lives in the past, and that struck a nerve and hooked me,” he said.

(Dina completed two years at Wake Forest before graduating with degrees in anthropology and art history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She went on to have a long career sculpting ceramic art pieces, many of which were inspired by her anthropology background, and teaching pottery classes.)

Archeologists Mark Wilde-Ramsing and Anne Corscadden working on the ocean floor. (Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

After Wilde-Ramsing graduated with a degree in anthropology, his parents gave him what at the time seemed like an odd gift, scuba gear, but maybe they foresaw something he didn’t. He learned to scuba dive at the YMCA in Winston-Salem and took a summer field school in underwater archeology at the University of North Carolina in Wilmington. Later, he earned a master’s in archeology from Catholic University and a Ph.D. in coastal resource management from East Carolina University.

He joined the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources in 1977 and spent the first part of his career exploring historic sites on land, including Native American sites in New Hanover County and Civil War sites at Fort Fisher outside Wilmington and at Fort Branch in Martin County. After moving to the department’s Underwater Archeology Branch as environmental review coordinator, he evaluated coastal construction projects — from large scale projects by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to the construction of mom-and-pop piers — to ensure the protection of shipwrecks and other historic underwater sites.

QAR wooden hull frames on the seabed. (Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

Then in late 1996, a private company searching for a Spanish treasure ship found a shipwreck in the Beaufort Inlet. Based on the size of the ship and the armaments and other artifacts found and historical accounts of where QAR sank, Wilde-Ramsing and other archeologists concluded that the ship had to be Blackbeard’s flagship.

The legend of Blackbeard — born Edward Thache in England (the spelling of his last name varies, but Wilde-Ramsing prefers Thache) — has grown over the centuries, but his flagship was largely forgotten.

QAR began its sea journeys in 1710 as Concorde, a French privateer and later slaveship. Blackbeard captured the ship, packed with 455 Africans, off the coast of Martinique in the eastern Caribbean Sea in November 1718. He increased the ship’s armaments and named his new flagship Queen Anne’s Revenge, likely a snub to the English queen’s successor, King George I.

Over the next six months, the heavily armed QAR and several smaller ships with up to 400 pirates under Blackbeard’s command seized and plundered merchant ships from the Caribbean to North and South Carolina.

QAR pewter plates, partial spoons and a crushed porringer. (Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

In June 1718, QAR ran aground on a sandbar in the Beaufort Inlet and was abandoned. Wilde-Ramsing and other archeologists and historians speculate that Blackbeard intentionally grounded the ship to split up what had become a large, unwieldy group of pirates.

Blackbeard and a smaller group of 40 pirates and 60 Africans set off on their own, presumably to keep more of the pirate loot for themselves. Three months later, a Virginia militia caught up with Blackbeard off Ocracoke Island on the North Carolina Outer Banks. He was killed and his severed head was taken back to Virginia.

More than 300 restored artifacts from Queen Anne’s Revenge are on display at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort. Artifacts can also be seen at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Southport, the Museum of the Albemarle in Elizabeth City, the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras, the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Tours are available of the Queen Anne’s Revenge Conservation Lab on the campus of East Carolina University in Greenville.

A brass mortar and pestle, recovered separately from the QAR site, were used to grind raw ingredients for compounds needed to treat wounds and ailments. (Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

Seven secrets of Blackbeard and the lost – and found – Queen Anne’s Revenge

1) Blackbeard probably wasn’t as ruthless as his legend suggests. His “brand” as a cold-blooded pirate was useful in getting merchant ships to surrender, often without having to fire a shot. Crews of captured ships were usually set safely ashore, sent on their way in smaller boats or “invited” to join the pirates.

2) When Blackbeard captured Concorde, he kept more than 157 Africans and 14 French crew members. The remaining 300 Africans and French crew were set ashore on a small island and given one of Blackbeard’s smaller ships. Blackbeard later sold at least half the Africans he kept on board before leaving the French Caribbean; some Africans joined the crew as freed men. Artifacts associated with the slave trade found at the QAR site include glass beads and portions of two shackles.

3) Three French surgeons from Concorde were forced to join the pirates after the ship’s capture. Medical items recovered include a urethral syringe, a cauterizing iron and fragments of apothecary jars. When Blackbeard’s fleet blockaded the port at Charleston, South Carolina, the “ransom” to lift the blockade was a chest of medicine.

Urethral syringe from the French surgeon's kit, left on board when QAR was abandoned. (Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

4) What did the pirates eat? Based on animal bones found at the QAR site, the ship likely carried pigs and perhaps even cattle. Iron cookpots, pewter plates, wine bottles and glassware also have been recovered. A ca. 1714 wine glass, embossed with crowns and diamonds, was made for the coronation of King George I.

5) “Sorry, golddiggers,” Wilde-Ramsing and Carnes-McNaughton write, no treasure has been recovered from QAR. Because the grounding and subsequent sinking of the ship was a slow-moving event — versus a storm that could quickly doom a ship — there was plenty of time to remove valuables. Only traces of gold dust, likely stolen from the French slave traders on Concorde, and four small coins have been recovered.

6) So what did they steal? Much of the plunder was simply what the pirates needed to sustain life at sea: food, clothes, guns and, of course, alcohol. The largest haul, “fifteen hundred Pounds Sterling, in Gold and Pieces of Eight” (worth about $250,000 in today’s dollars) was taken from captured ships during the Charleston blockade and surely removed after the ship ran aground.

7) QAR was heavily armed with up to 40 cannon; 29 cannon, along with numerous cannon balls, have been recovered. Even though the crew had plenty of time to abandon ship, the cannon were likely too cumbersome to move. Conversely, few personal weapons have been found; the pirates took their pistols and daggers with them to pillage and plunder another day.

Source: “Blackbeard’s Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne’s Revenge,” by Mark U. Wilde-Ramsing and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton (University of North Carolina Press, 2018)

U-shaped portion of a leg iron found at the QAR site, a sign of its earlier life as a French slaveship. (Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)