Unlike Will Ferrell’s title character in the 2004 film “Anchorman,” the following alums are way too humble to tell you that they’re kind of a big deal. But they are. They’ve earned something very few Wake Forest graduates have: a Rhodes Scholarship.

A Rhodes Scholarship allows a student, age 19 to 25, to pursue a second bachelor’s, a master’s or a doctorate at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom with all educational expenses covered and a generous living stipend. The program is named after Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902), a former prime minister of Cape Colony — in what is now South Africa — who established the scholarship through his will.

To get a sense of just how difficult it is to win a Rhodes Scholarship, take a look at these numbers. It’s estimated that about 2,500 U.S. students begin the application process each year. They must submit a transcript, a list of activities, five to eight letters of recommendation and a 1,000-word personal statement, among other things. They also must have their university’s endorsement, which roughly 900 receive. Next, 230 are interviewed in 16 regions, with 32 (two from each region) chosen. Elsewhere in the world, 68 students also are tapped for a total of 100 scholars.

Beyond having outstanding grades, applicants must show the selection committee their leadership, character and service — though the criteria have changed over time. For instance, athletic excellence was more of a focus in the past, and women weren’t eligible until 1977.

“Winning takes a combination of extraordinary talent, hard work and luck. Some of our best students have lost,” says James Barefield, a Wake Forest professor emeritus of history who helped identify University high achievers, encouraging them to apply for the Rhodes and shepherding them through the process, especially during the 1980s and ’90s.

Tom Phillips (’74, MA ’78, P ’06), associate dean and director of the Wake Forest Scholars Program, took the baton from Barefield around 2000. One thread he notices among the Rhodes winners and near-winners is intellectual curiosity. “It has to be somebody who is really going to use his or her mind, develop it and activate it to some purpose,” he says.

Wake Forest’s 13 living Rhodes Scholars, who graduated between 1986 and 2013, work in fields as varied as medicine, law, economics, clean energy and academia in locations all over the globe. In the true spirit of Pro Humanitate, all are using their gifts to help others and address some of the world’s biggest problems.

JENNIFER BUMGARNER (’99)

Focusing on Climate and Clean Energy Policies

* * * *

Growing up in Hickory, North Carolina, JENNIFER BUMGARNER (’99) went to a rural public high school with few resources.

“We didn’t have a very high college attendance rate,” she says. “My grandparents didn’t go to college, and my parents had only two-year degrees from community college.” So landing a full, merit-based Reynolds Scholarship to Wake Forest was a feat.

Bumgarner, a political science major, loved taking a class called political science research methods with Peter M. Siavelis, now professor and chair of the Department of Politics and International Affairs. “I’m not a research methodology person, but I still remember things from that class. And some days I don’t remember my children’s names,” she says.

When it came to the Rhodes Scholarship selection process, the hardest part for her was the cocktail hour the night before the regional interviews. “I’m very much an introvert. And particularly at that point in my life, I was not confident in social settings. I grew up in a family of teetotalers in a working class community. So going to a private club in D.C. with a bunch of incredibly smart people, where everybody was jockeying for position, it was a nightmare. I thought, I just need to survive. I need to get through tonight without spilling a drink,” she says.

But Bumgarner has an inner drive that helped her power through the discomfort. “I worked really hard because I’d seen what it was like when people have limited opportunities for learning and education. And I knew I had an opportunity for a different path,” she says. After she won the Rhodes, her parents were ecstatic. And her grandmother? “I don’t think she met anyone for two years anywhere, anytime, who probably didn’t find out I was a Rhodes Scholar. Bless her heart,” she says.

After earning a master’s in social policy and social work at Oxford, Bumgarner had planned to stay for a doctorate, but then 9/11 happened and her grandmother got sick, both of which made her suddenly miss home. So she headed back to North Carolina. She worked in the governor’s office, where she began to immerse herself in energy and climate issues. She went on to become the assistant secretary for energy at the North Carolina Department of Commerce.

For the past seven years, she’s been in Raleigh at the Energy Foundation, a national group focused on climate and clean energy policies. “We do a lot of work with traditional environmental allies, but we also do a lot of work with other allies, including conservatives, businesses and policymakers,” she says. “I’m really proud of the fact that I’ve figured out how to work with a diverse group of people — and align them on strategies that actually get things accomplished and help move the ball forward on an issue that otherwise can be really, really divisive.”

MICHELLE SIKES (’07)

Using Sports to Understand African History

* * * *

If MICHELLE SIKES (’07) ever jogged past you on campus, all you likely saw was a blur. In 2007, she won the NCAA Outdoor Championship in the 5,000 meters (3.1 miles) with a blistering time of 15:16:76 in the final race of her senior year. “That was the highlight of my running career. I was so euphoric,” she says.

If MICHELLE SIKES (’07) ever jogged past you on campus, all you likely saw was a blur. In 2007, she won the NCAA Outdoor Championship in the 5,000 meters (3.1 miles) with a blistering time of 15:16:76 in the final race of her senior year. “That was the highlight of my running career. I was so euphoric,” she says.

She won the NCAA championship by upsetting Texas Tech track star Sally Kipyego, a Kenyan who went on to win an Olympic medal.

Sikes credits her coach Annie Bennett for teaching her how to run the race hard and keep pushing. Bennett did have some insider insight: She’d won that exact race herself in 1987.

Sikes, a five-time All-American in college, still holds school records in 1,500 meters, the mile, 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters. She was inducted in 2018 into the Wake Forest Sports Hall of Fame.

The mental focus that Sikes learned through running helped her in academia. “The core of running is making sure you’re consistent. If you can stay healthy and run day after day, you’ll do as well as your body will let you do. That discipline — that daily getting up and getting out the door — is pretty much 90 percent of the sport,” she says.

A mathematical economics major with a minor in health policy and administration, Sikes was excited by the Rhodes Scholarship opportunity because she’d never left the country, and it was too hard to squeeze in a semester abroad with her busy athletic schedule.

She deferred the Rhodes for a year so she could represent the United States in the IAAF World Championships in Athletics in Osaka, Japan, in the late summer of 2007. For a few years post-college, Sikes was sponsored by Nike, which provided her a salary to run professionally and covered her travel and medical expenses.

She deferred the Rhodes for a year so she could represent the United States in the IAAF World Championships in Athletics in Osaka, Japan, in the late summer of 2007. For a few years post-college, Sikes was sponsored by Nike, which provided her a salary to run professionally and covered her travel and medical expenses.

At Oxford, she got a doctorate in economic and social history, focusing on female distance runners from Kenya. She had noticed a lot of academic research on male distance runners from Kenya, but nothing on the women, who emerged much later than the men. “I was really interested in the pioneer generation of women who were the first Kenyans to compete at the international level. I wondered how they navigated the obstacles that they faced and what those obstacles were,” she says.

Since Oxford, Sikes has pursued a career in academia. She went on to work as a lecturer at a couple of universities in South Africa, and she’s currently an assistant professor of kinesiology and African studies at Pennsylvania State University. “I’m really passionate about using sports to understand African history. More generally, I’m interested in using team sports as a lens through which you can understand societies.”

RICHARD CHAPMAN (’86)

Teaching Computer Science

* * * *

RICHARD CHAPMAN (’86) was always familiar with Wake Forest as a kid because his mother, Leila Smith Chapman (’60, P ’86), was a member of the first freshman class on the Winston-Salem campus.

A Carswell Scholar, Chapman was invited to a special room in Tribble Hall (A109, The Barefield Honors Seminar Room in honor of James Pierce Barefield) where the honors students would hang out. “That was really the center of my academic and social life. We’d be there all hours of the day and night, discussing all kinds of things — and it was fabulous. It was the kind of academic life I’d always dreamed of, and I think it really did set the course of my life to go on and do a Ph.D. and be a faculty member. I couldn’t imagine not having that kind of intellectual vitality,” he says.

One faculty member who inspired him was John Baxley (P ’91, ’92), now professor emeritus of mathematics. They worked together on research related to differential equations and published a paper. “There was a mentoring relationship there that was meaningful to me,” says Chapman, who majored in math.

While Chapman was finishing high school and beginning college in the early 1980s, personal computers were just becoming available, and he was immediately drawn to them. “For the first time, it was possible to sit interactively with a machine and develop software in the way that people do now. You didn’t have to punch a deck of cards and submit it and get a printout back. You could just sit at the screen and type,” he says. “A friend of mine got a microcomputer in junior high school, and I learned to program on that. It was just kind of magical. The idea of creating a set of instructions that can solve a problem absolutely fascinated me.”

This made going to Oxford a dream. “Oxford is one of the world leaders in mathematics and has been for centuries. The kind of computer science I was interested in at the time was very mathematical. The particular problem was how do you prove that a program does what you say it does, assigning semantics or meaning to a computer program the way we could assign semantics to human language. And Oxford had really done the groundbreaking work there. So it was truly a unique experience to get to study with these world-class minds about that problem,” says Chapman, who was part of the first graduating class at Oxford to receive a bachelor’s in mathematics and computation.

After getting a Ph.D. in computer science at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, he joined the faculty at Auburn University in Alabama in 1993. He holds several titles there, including associate professor and director of the computer science and software engineering online undergraduate program. The latter position is taking most of his time right now. “We started building that from zero and enrolled our first students in January of 2018, so I’m mostly an administrator at this point, trying to get that program off the ground,” he says.

Chapman calls teaching “immensely gratifying,” and one of his favorite roles is working on interdisciplinary projects with students. “I have students who have done musical collaboration over the internet, and I have one now who is doing computerized roasting of coffee. Some faculty members say they always send me the weird projects, but I like the weird ones.”

REBECCA COOK (’05)

Improving Health Care for the Poor in Liberia

* * * *

Whenever Rebecca Cook (’05) sees people in the United States flip out over temporarily losing electricity during a storm once in a while, it’s hard for her to muster a similar level of outrage.

She grew up in Kenya, about 35 miles northwest of the capital city of Nairobi in a rural town called Kijabe. Electricity outages were fairly common. “As kids, we actually loved it because we lit candles and didn’t have to finish our homework,” she says. Water usage was sometimes limited due to droughts. “We’d take one-minute showers and save the water from the shower to do the laundry,” she says.

The daughter of two teachers, Cook went to an international Christian school and found out about Wake Forest through family friends who live in Winston-Salem and had worked in Kenya. At Wake Forest, she experienced culture shock and found comfort in joining small communities such as the InterVarsity Christian Fellowship and becoming a resident adviser. She often walked through Reynolda Gardens or had dinner with friends in Reynolda Village.

Majoring in biology with a minor in international studies, she followed a pre-med path. In elementary school, she had visited the children’s ward at the local hospital to color and play with young patients. She knew she wanted to become a doctor and learn about all the social factors that drive quality of life and contribute to why people get sick. “Do they come to the hospital? Or do they go to a local healer? Do they buy medication online?” she says.

Cook embarked on years of graduate school. She earned a master’s in medical anthropology and a master’s in global health science at Oxford, then went through medical school and residency, specializing in both pediatrics and internal medicine so she could care for patients from birth to death. She then completed a two-year fellowship in pediatric global health.

Cook embarked on years of graduate school. She earned a master’s in medical anthropology and a master’s in global health science at Oxford, then went through medical school and residency, specializing in both pediatrics and internal medicine so she could care for patients from birth to death. She then completed a two-year fellowship in pediatric global health.

Her current job has brought her back to Africa — this time to the west coast — to Liberia, one of the poorer nations in the world that has been torn apart in recent years by civil war and an Ebola epidemic. She’s the director of medical education and the child health lead for Partners in Health in Liberia. Six weeks out of the year, she returns to the United States to teach at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where she keeps an academic appointment as clinical instructor in pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

One major part of her job in Africa is caring for patients at a hospital where resources are limited. “We see a lot of malaria and malnutrition. Tuberculosis is very prevalent. There’s some HIV. We also see non-infectious diseases such as kidney and heart disease, diabetes and cancer, even in children,” she says.

The other large part of her job relates to implementing new medical technology and protocols at the hospital and educating the staff. Here are a few examples of life-saving changes that Partners in Health has been making in Liberia: having an oxygen generator unit built because the hospital would often run out of oxygen, bringing in incubators and phototherapy for newborns and leading workshops on how to resuscitate newborns when they’re not breathing. The organization hires and trains community health workers who visit patients in their homes, help pay their transportation costs to and from the hospital and give them food with their medications so they can tolerate them.

“The need is tremendous, and I’m one person from a different culture. It’s much more strategic to be investing in the providers in the place that you’re working — not just setting up a clinic for a few days and leaving. I hope that I can stay here long enough to help build a solid training program for Liberian doctors. I would love it if we’re able to hire a Liberian doctor for my job someday.”

ROBERT ESTHER (’91)

Treating Patients with Bone or Joint Cancer

* * * *

Although ROBERT ESTHER (’91) was on a pre-med track at Wake Forest, he majored in history with a minor in biology. “I liked reading and writing. History combined some literature and narrative elements, politics, psychology and economics.

Even though it’s the humanities, it has a little bit of a multidisciplinary feel to it,” he says. One of his standout professors was James Barefield, now retired. “Barefield was very insightful. He was very good at asking questions and getting you to challenge your own thoughts and assumptions about a given subject,” says Esther.

He continued this line of study at Oxford, getting a bachelor’s in modern history. After that, his focus turned to science. Both his older sister and brother had become physicians, and he was inspired to follow in their footsteps. After several more years of graduate school, he became an orthopedic oncologist and has spent the past 12 years at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

About 80 percent of his time is spent doing clinical work such as seeing patients who have cancer in their bones or joints and performing surgeries. His favorite part of the job is treating children, who make up about one-third of his patients. “Most of the time, especially in light of what they’re facing, they’re all very resilient and optimistic and fun to interact with. It makes you kind of rethink what constitutes a bad day,” he says.

The other 20 percent of his time is spent doing administrative and teaching work, training medical students and residents. “Most of what I learned about teaching I learned from people like Jim Barefield and (Provost Emeritus) Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93). They taught me to care about students and be thoughtful about getting them to think and ask good questions,” he says. Along the way, Esther also learned what not to do. “I’m not much of a shouter. Typically, yelling a lot and making the operating room a threatening environment isn’t great for learning.”

CAROLYN FRANTZ (’94)

Minding the Law in Technology

* * * * *

CAROLYN FRANTZ (’94) didn’t take a traditional route to Wake Forest. In the spring of her junior year of high school, while looking at her senior class schedule (almost all Advanced Placement courses), she thought, “Why not just go to college?”

That it was too late to apply didn’t stop her. “It was a feeling of ‘Why do I have to do things the same way everyone else has done them?’” she says. Luckily, her friend’s dad (a Wake Forest booster) helped her get in that fall.

Frantz majored in philosophy and joined a choir and an early instrument ensemble. She fondly recalls having the freedom to explore and feeling supported. “What was good for me, as the person I was at that time — pretty open-minded, unmoored, mostly just curious without much direction — was that whenever I wanted to learn something or try something, there was somebody there who would take me seriously and help me,” she says.

Growing up, Frantz had been exposed to respectful-but-vigorous debates between her conservative father and liberal mother, which taught her how to think and talk about ideas. So it’s no surprise that she got into a heated conversation with the Rhodes selection committee during the interview process.

“We really mixed it up. We were talking about the proper place in society of religious zeal. … At the end, one person asked me, ‘Why do you want to be a Rhodes Scholar?’ I said, ‘I don’t, particularly. I’d just like to go to Oxford, and this is a way,’” she says. Frantz left assuming she had squashed her chances, but later in life, while interviewing Rhodes applicants, she realized there was unintentional wisdom to her approach. “Some students are wound so tight. They’ve wanted to be Rhodes Scholars since they were 7, and their resumes are perfect and shiny. It’s not very inspirational. It’s the people who care about what they do and are doing it whether or not you’re there that you end up liking,” she says.

At Oxford, Frantz transitioned from philosophy to law, receiving a second bachelor’s in jurisprudence and a master’s in legal research. “What drew me away from philosophy was that, in law, you could figure out a hard problem and there was an outcome, there would be action,” she says. Then came University of Michigan Law School, where she graduated first in her class, and various jobs, such as being a trial lawyer for 11 years.

Now, as vice president, deputy general counsel and corporate secretary at Microsoft Corp. in Seattle, where she’s responsible for corporate governance and corporate law, Frantz has found her niche. She says: “As a Rhodes Scholar, they ask you to contribute to society. As a law firm lawyer, I felt guilty that I hadn’t lived up to that implicit promise. I didn’t feel that what I was doing at that time was a social good. It wasn’t a social bad, necessarily, but maybe it was more about making money. Right now, the tech industry is a place where helping them get things right can really have a huge impact on social issues.”

CHARLOTTE OPAL (’97)

Making Trade More Equitable and Protecting Our Forests

* * * *

CHARLOTTE OPAL (’97) got a memorable peek at wealth distribution as a teen. Though she attended a fancy public high school in Fairfax County, Virginia, Opal was in the D.C. Youth Orchestra, which meant playing music twice a week at a different public high school that had very few resources.

“It was quite a contrast. It just seemed so unfair,” she says.

Opal double-majored in economics and math. “I’ve always liked math, and I’ve always liked people. Economics is a math-mediated way to think about human interactions and how people buy and sell things from each other and trade,” she says. During her time at Oxford, she received a master’s in development studies and a master’s in business administration.

Opal’s post-Oxford life included stints in New York City and San Francisco, but for the past 12 years, she’s lived in the French-speaking town of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, with her Dutch husband, Caspar, whom she met at Oxford, and her trilingual kids, Chet, 9, and Angelique, 7. She loves it there. “People in Switzerland recycle more, eat more organic food and think about waste. You’re living in a small country, so you can’t just expand into the frontier, into suburbia. There are no landfills here. It’s a smaller scale of life, which I like, and more cooperative. You can’t avoid your neighbors — they’re everywhere,” she says.

In fact, she’s so beloved by her neighbors that she was elected to head her town’s parliament. She runs their meetings, and as a group, they can pass legislation. “I was recruited and then promised that I wouldn’t win,” she says. “I give speeches and do ribbon-cuttings. I represent the town in official ceremonies and welcome visitors.”

Opal has held a variety of positions in her career. She worked for a company that imported food from conflict regions, then moved to Fair Trade USA, a certifier of Fair Trade coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, bananas and other products. Later, she took a job in the sustainable biofuel industry — “using plants in our cars, basically,” she says. One proud achievement was persuading Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream to source a Fair Trade coffee extract for their Coffee Coffee BuzzBuzzBuzz flavor.

Opal has held a variety of positions in her career. She worked for a company that imported food from conflict regions, then moved to Fair Trade USA, a certifier of Fair Trade coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, bananas and other products. Later, she took a job in the sustainable biofuel industry — “using plants in our cars, basically,” she says. One proud achievement was persuading Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream to source a Fair Trade coffee extract for their Coffee Coffee BuzzBuzzBuzz flavor.

Now Opal is an independent consultant, working with non-governmental organizations that work with companies. “I’m mostly working now on helping companies get their supply chains deforestation free. I think our big planetary struggle is that we’re converting all of our forests and wildlands to agriculture, and it’s just not sustainable,” she says.

She also serves as a lecturer for several universities. “I’m so grateful to my professors for how much they gave us. I’ve been trying to give back in that way by teaching. You can’t possibly read everything or experience everything, so having someone distill the important things down and feed them to you is just precious. I’m only now realizing what an amazing gift that was.”

E. SCOTT PRETORIUS (’89)

Bringing Radiology to Rural Areas

* * * *

Winning a Rhodes Scholarship seemed more possible to E. SCOTT PRETORIUS (’89) after living on the same hall in his freshman year with Richard Chapman (’86) and having Maria Merritt (’87) as a student adviser.

What pushed Pretorius, an English and chemistry double major, over the edge to apply was a semester at Worrell House in London with now-retired theatre professor Harold Tedford (P ’83, ’85, ’90). “After that, I was really eager to return to the UK,” says Pretorius.

He received a bachelor’s in English at Oxford before heading to medical school and becoming a radiologist. A former Wake Forest faculty member — then Associate Professor of Chemistry Susan Jackels — helped inspire Pretorius to choose this scientific field. While doing research with her, he was fascinated by magnetic resonance imaging.

In 1999, before joining the faculty at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and co-writing a textbook called Radiology Secrets, tragedy struck in his personal life. His former partner of six years, Robert, was assaulted in an act of anti-gay violence so vicious that it left him needing a wheelchair for life. To this day, Pretorius remains involved in his care. “He has difficulty forming new memories, but his memory of the time we were together remains very much intact,” he says.

Pretorius left academia in 2005 after starting a business in teleradiology, which allows small hospitals in rural communities (which might not be able to afford radiologists on site 24/7) to send images to radiologists working remotely. Pretorius sold the business in 2016 and has been interpreting radiology studies from home ever since.

One factor that motivated Pretorius to work from home: wanting to spend more time with his kids. In 2012, he welcomed twins — Max and sister Jackie — with the help of an egg donor and surrogate, becoming a single dad at the age of 45.

In his spare time, Pretorius travels the globe. He’s visited 84 countries, and choosing his most memorable vacation is difficult. “One of my favorite trips was a self-drive through Namibia. It’s a stunningly beautiful place which receives relatively few visitors. Antarctica is one of the places I fantasize most about returning to,” he says. But there’s also the Temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, Machu Picchu in Peru and many others that come to mind. “I haven’t yet traveled internationally with the kids, but that’s definitely something I’m looking forward to.”

MARIA MERRITT (’87)

Tackling Bioethics in South Africa and Uganda

* * * *

At Wake Forest, MARIA MERRITT (’87) was a walk-on to the cross-country and track teams and majored in biology, thinking she might become a doctor. But her passions pulled her in a different direction.

She spent an incredible semester at Casa Artom in Venice, Italy, where she rode bicycles around the region with fellow Rhodes Scholar Richard Chapman (’86). When it was over, “I still had this fascination with all things Italian.” When she won the Rhodes Scholarship, she decided to study for a bachelor’s in philosophy and modern languages, with a focus on Italian.

Her Oxford experience was invaluable. “I was never smarter than the day I left that place. It really pushed me to max out on what I was capable of learning and mastering. You acquire a deep understanding of the subjects. I hope that has helped me to contribute at the highest possible level in whatever else I’ve done since then,” she says.

After obtaining a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of California, Berkeley, Merritt took on a postdoctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health, an assistant professorship at William & Mary and a faculty fellowship at Harvard. For the past 12 years, she’s served on the faculty at the Berman Institute of Bioethics and the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

Like many of her fellow faculty members, Merritt has to fund significant portions of her salary and research by applying for competitive grants. “You have to write a very in-depth proposal, show the quality of your work and make it accessible to people in different disciplines. That takes writing it over and over again. It was the same kind of experience preparing for my exams at Oxford,” she says.

One project for which she obtained funding examines the experiences of people undergoing treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa and Uganda. Policymakers there and elsewhere will face a variety of publicly funded treatment options as new drugs are developed. For instance, one cheaper standard treatment might restore people’s physical health. But it takes as long as two years, and patients face emotional, social and financial problems if they must do physical labor to support their families. Another treatment might be more expensive but just as effective and requires much less time in a hospital. The project’s goal is to help policymakers evaluate the social impacts before making choices.

Beyond her research, Merritt also has a leadership role in her department in looking after student well-being. “The thing I’m proudest of is being recognized by the Bloomberg School’s Student Assembly for ‘Outstanding Commitment to Student Success’ in 2017,” she says.

She says she can trace this directly back to her early exposure at Wake Forest to people like Professor Emeritus of History James Barefield and Tom Phillips (’74, MA ’78, P ’06), associate dean and director of the Wake Forest Scholars Program.

“I often ask myself, ‘What would they do?’ First of all, they’d be way funnier than I am. But they were so invested in student success, and that is the most important value that I learned there.”

LAKSHMI KRISHNAN (’06)

Merging Medicine and Literature

* * * *

LAKSHMI KRISHNAN (’06) grew up in a variety of places: India, the United Kingdom, Michigan, Texas and, finally, Tennessee. When she visited Wake Forest, she fell in love with the campus.

“I just thought it was the most civilized place. Everyone seemed very gentle; it was peaceful. Yet at the same time there seemed to be a very quiet radical academic environment. This place was very genteel and Southern, but then you’d walk into Tribble Hall and there were progressive posters and talks. I really liked that combination,” she says. “Coming from this immigrant, cosmopolitan family and growing up in the South, I felt like this bundle of contradictions. And Wake, to me, seemed like a place that was exciting because it was also contradictory.”

An academic omnivore, Krishnan double-majored in English and German and also studied chemistry. “I was a voracious reader growing up. My dad bought me 19th-century British novels. I didn’t grow up reading what a lot of American kids read, like Dr. Seuss or Maurice Sendak. I read the kids’ version of ‘The Count of Monte Cristo,’” she says.

Krishnan found the academic environment at Wake Forest to be extraordinary. “There was just something about the culture that encourages people to be Renaissance liberal arts thinkers. Part of that may just be the geography of the space. Wake felt like this microcosm of knowledge. In the morning, I could be completely surrounded by scientists or pre-med people, and then in the afternoon, I could bounce into a very different world. Now I realize what a luxury that was. Now I’m in a world where fields of discipline and ideas are so siloed,” she says.

Her doctorate in English literature from Oxford allowed her to dive deeply into Victorian literature, and having so much unstructured time gave her the opportunity to perform in several plays. On stage, she particularly loved playing Cleopatra in “Antony and Cleopatra” and Rosalind in “As You Like It.”

Her doctorate in English literature from Oxford allowed her to dive deeply into Victorian literature, and having so much unstructured time gave her the opportunity to perform in several plays. On stage, she particularly loved playing Cleopatra in “Antony and Cleopatra” and Rosalind in “As You Like It.”

Medical school and residency followed, and Krishnan is now a fellow in the Division of General Internal Medicine and the Institute of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, where she’s crafting a career that involves a mixture of research, writing, teaching and clinical practice.

The subject of her research is diagnosis and diagnostic reasoning. She’s writing a book examining diagnosis in the 19th and 20th centuries in the United States and Britain alongside detective fiction. She’s weaving in stories from her own experiences as a doctor and contemporary clinical questions. “It’s the idea that diagnosis is a process akin to criminal detection,” she says. “It’s relevant now, especially as we think about how diagnosis is something that might be replaced by artificial intelligence, algorithms or machine learning. As doctors, we’re asking ourselves almost existential questions like what is the role of the doctor in contemporary medicine?”

JIM O’CONNELL (’13)

Enhancing His Hometown

* * * *

If you ask JIM O’CONNELL (’13) about his parents, you’ll get an unusual answer. As he wrote in his “Constant & True” essay in the Fall 2016 issue of this magazine: “My mother’s name is Kathy, and my father’s name is Reproductive Sample No. 119.”

In 1989, at the age of 39, Kathy wanted to be a mother but hadn’t yet met the right person, so she used a sperm sample from an anonymous donor to get pregnant. She was always open with Jim about her decision, and one day, when she put the donor’s identifying information into a database — ping! — there was a match. That meant that Jim could contact (and potentially meet) his biological dad. But he wasn’t ready. “I was 15, playing high school football and not interested in this crazy deep question of my existence,” he says.

When he turned 23, his curiosity got the best of him, and they met for coffee so he could finally get some closure. Then they went back to their separate lives. “What I realized was that I wasn’t shaped by the absence of this guy; I was shaped by the presence of so many other folks, from my mom to family members to coaches to teachers to friends,” he says.

Wake Forest also shaped him. A politics and international affairs major and a member of Sigma Chi fraternity, he volunteered for two extracurricular roles that he calls formative. One was being named when he was a sophomore as a co-chair on the Honor & Ethics Council, where he helped decide whether a student who got in trouble for, say, plagiarism deserved probation, community service, suspension or expulsion. “I learned a ton about leadership in tough scenarios,” he says.

The other was being the sole student trustee on the University’s Board of Trustees during his senior year. He voted on issues concerning academics, athletics, student life and more. This gave him a glimpse into how a giant institution with a multimillion-dollar endowment is run.

After graduation came a yearlong fellowship in President Nathan O. Hatch’s office, which involved working on special projects, then two master’s degrees at Oxford, one in U.S. history and one in religion.

Post-Oxford, O’Connell was ready to apply to be an officer in the U.S. Navy when he happened to be introduced to someone special. It was Jeff Vinik, who owns the Lightning professional hockey team in O’Connell’s hometown of Tampa, Florida, and is also a philanthropist who is playing a large role in revitalizing the downtown area that surrounds his team’s arena.

O’Connell couldn’t pass up the chance to work for Vinik and now serves as president of the Vinik Family Office. Alongside Vinik, O’Connell manages the group that oversees Vinik’s private investments, community leadership work and anything related to his foundation and his involvement in public policy. One of O’Connell’s main projects over the past two years has been helping Vinik build a technology/startup ecosystem in Tampa. The innovation hub is scheduled to launch in 2019.

On top of all this success, Jim is a happy newlywed — just last year he married a fellow Deac, Karli (Thode) O’Connell (’14). “Of all the amazing things about Wake, the best part for me really was meeting her. It’s rare to have this place that brings together so many smart, driven, passionate, creative people.”

BRANDON TURNER (’12)

Specializing in Radiation Oncology

* * * *

BRANDON TURNER (’12) lived in eight states growing up as his dad moved to work his way up the ladder at an air conditioning company. “At first, I saw it as an adventure. As I got older, it got harder. But I also think it was good for me.

It forced me to become comfortable with change, to learn not to fear it. In addition, it forced me to learn how to connect with people quickly,” he says.

Once he got to Wake Forest, Turner found himself interested in everything. During his sophomore year, Abdessadek Lachgar, a chemistry professor who later became a mentor, had a conversation with him that helped him narrow his focus. “He said, ‘Usually students by this stage have figured out who they are and what they want to be, and I look at you, and you’re just all over the place. I think you need to figure it out.’ I remember initially being upset by it, but it was accurate. It was the first time I started to think: I need to get serious about something and figure out a clear path,” says Turner.

Turner settled on biophysics for a major and sociology for a minor and still found time to squeeze in some rugby. Through the Rhodes Scholarship, he received a master’s in radiation biology/radiobiology and almost completed a second master’s in physiology, anatomy and genetics — but the Stanford School of Medicine lured him to California. He’ll find out where he matches for his residency in March and he’ll finish medical school in June.

As a doctor, he will specialize in radiation oncology. Radiation is a form of cancer treatment that uses beams of high energy to target tumors. It kills cancer cells and can help prevent cancer from spreading and relieve pain or other symptoms.

One major problem Turner hopes to help solve is how to individualize treatment better. This can make the treatment more precise and lead to clues that might offer a cure.

“As health problems become more complicated, we have to engage with another level of information. Sometimes that includes genetics, like DNA, RNA and proteins. This is the information that really makes up the pathologic process. The challenge with this, though, is that a single person has 20,000 genes and can also have tens of thousands of mutations. It’s difficult for one person to comprehend and analyze all that, especially when you start scaling this over millions and millions of patients. So we have to learn and develop new tools that are able to extract insights from all of this information because we’re just now able to collect it, but we don’t really know what to do with a lot of it yet.”

JENNIFER HARRIS (’04)

Crafting Economic Policy

* * * *

JENNIFER HARRIS (’04) has always had discipline. During most of her childhood, she spent three hours a day practicing gymnastics, working her way up to Level 9, just shy of the “Elite” level.

She was invited to train with famed coach Béla Károlyi before the ’96 Olympics but got hurt and retired at 16. Nevertheless, the work ethic that she developed during that time period came in handy later when she began her career.

Harris was first exposed to economics while competing in academic decathlons in high school. She had a deep interest in foreign policy because her dad was a U.S. Navy Reserve intelligence officer who traveled once a month, sometimes to work on top-secret products.

Wake Forest was an excellent fit. “I appreciated the length that the faculty would go to make the really serious students feel at home. Professors were thrilled when we showed up at their door during office hours,” she says. A double major in economics and political science, Harris did refugee work in the Balkans and Eastern Europe over multiple summers, thanks to a Graylyn Scholarship. Oxford gave her the chance to get a master’s in international relations.

Harris launched her career as a staff member on the National Intelligence Council, which led to joining the Policy Planning Staff of the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C., where she assisted Secretaries of State Condoleezza Rice, Hillary Clinton and John Kerry. “When something big happened in the world — like the Arab Spring — it was the job of my office to come up with a theory of the case and design the strategic approach that U.S. foreign policy should take,” she says.

While tackling these jobs, she somehow squeezed in a law degree from Yale Law School, commuting to New Haven, Connecticut, one day a week and stacking her classes. “I basically lived on Amtrak. I look back on those years and think of them as the ‘running years.’ I remember being out of breath a lot,” she says. Her husband, Sasha, is the son of one of her law professors. Even though she didn’t have the best attendance in her now-father-in-law’s class, “I think he’s mostly forgiven me,” she says.

Harris was particularly impressed with Hillary Clinton. “If we were in a meeting and I hadn’t spoken yet, especially given the gender dynamics, I’d appreciate the way she’d make space for soliciting the opinions of a young woman in the room,” she says. “And she read her homework. Clinton came to meetings prepared with a way of driving them and making them productive for everybody. It didn’t always feel like that.”

Clinton must have been similarly impressed with Harris because her campaign asked Harris to help develop economic policy for the 2016 presidential race at the Brooklyn, New York, headquarters. The results of that election were, of course, crushing to Harris. “Sasha and I were thinking about starting a family. I would look on the subway at the little kids, and it wasn’t clear what sort of America we’d be handing them,” she says. In December 2017, they had a boy named Shiloh.

Over the last few years, Harris has co-written a book called “War By Other Means,” moved to San Francisco and now works as a senior fellow at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, a philanthropic group. She is directing a two-year, $10 million project. A lot of old economic theories, says Harris, linger as orthodoxy — even in the face of evidence that they’re not working well.

“Look at the amount of inequality we have and middle-class wage stagnation. Average real wages have fallen even as we have record low unemployment. That’s not what our standard economic theories teach us. The idea is to take a whole lot of criticisms that are accurate and important and turn them into a positive vision to replace a lot of these standard models of thinking. The hope is that we can, with a little bit of philanthropic capital, start an intellectual counter-revolution.”

FAMOUS RHODES SCHOLARS

President Bill Clinton, seen here speaking at Wake Forest, is a former Rhodes Scholar.

- MSNBC host Rachel Maddow

- ABC host and former Democratic adviser George Stephanopoulos

- Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J.

- Former Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal

- Politician and NBA star Bill Bradley

- Journalist and lawyer Ronan Farrow

- Former U.S. National Security Advisor Susan Rice

- Retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter

- Actor and musician Kris Kristofferson

- Author and journalist Naomi Wolf

- Retired Army Gen. Wesley Clark

- Columnist Nicholas Kristof

- Physician and author Siddhartha Mukherjee

- Surgeon, writer and public health researcher Atul Gawande

- Journalist and political commentator E.J. Dionne

- Former President Bill Clinton (completed only one year of his two-year degree)

———sidebar———

———sidebar———

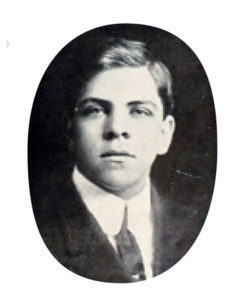

THE MYSTERY SCHOLAR

After nearly 90 years, a Wake Forest connection to a Rhodes recipient is unearthed.