Illustration by Jakob Hinrichs

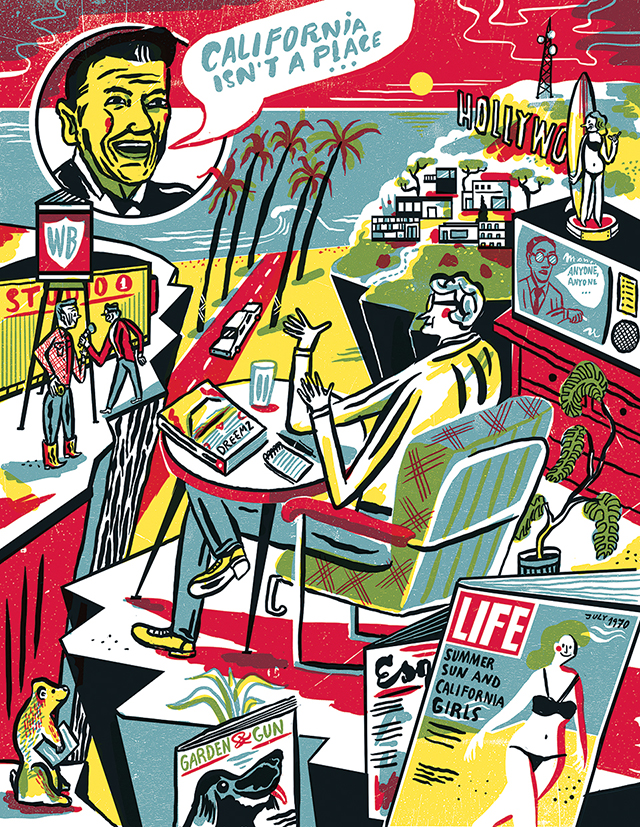

California isn’t a place, it’s a way of life. That’s what Ronald Reagan told me just after my sophomore year at Wake Forest. I had moved to Los Angeles for two jobs — to work for the former president as an intern, and for writer Benjamin J. Stein as a researcher.

When Reagan said that, we were standing in his personal office in Century City, in the very building made famous as Nakatomi Plaza in “Die Hard.” Listening to Reagan, who moved here from Iowa when he was 26, talk about the state where he forged his destiny was powerful. From the 34th floor of his office I could see the entire L.A. basin, with its cluster of skyscrapers downtown, and edges that touched the Pacific Ocean and receded into desert mountain ranges. Having traveled from my home state of North Carolina to California often in my boyhood years, I thought I had a good sense of the state and what Reagan meant.

As a 14-year-old who’d become a renowned expert on “The Andy Griffith Show,” I came to Los Angeles to meet one of the show’s principal writers, Everett Greenbaum, a TV veteran who also worked on “M*A*S*H.” He regaled me with secrets of writing in Hollywood and planted the earliest seeds of my own dream of working in the industry.

As a 14-year-old who’d become a renowned expert on “The Andy Griffith Show,” I came to Los Angeles to meet one of the show’s principal writers, Everett Greenbaum, a TV veteran who also worked on “M*A*S*H.” He regaled me with secrets of writing in Hollywood and planted the earliest seeds of my own dream of working in the industry.

As my mid-teens turned into my late teens, I grew obsessed with politics and was fascinated by its relationship with Hollywood. I read “Dreemz,” a diary by my future employer Ben Stein that memorialized his first year in California, and it became something of a primer for me. Here was a guy who graduated from Yale Law School and served as a trial attorney at the Federal Trade Commission, a speechwriter in the Nixon and Ford White Houses, and a columnist for The Wall Street Journal. But then Ben moved to L.A., went to work for Norman Lear, bought a Mercedes 450 SLC and became a sitcom and film writer, actor and game show host. (Only to become most famous for his single scene in “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.”)

During the summer when I interned for Reagan, Ben took me to my first sushi restaurant, introduced me to Malibu (where he still has a house), and showed me one of the first 24-hour gyms in the country.

Yes, I thought I had a pretty good sense of Hollywood. When I was a sophomore, I moderated Ted Turner’s tribute to the 30th anniversary of “The Andy Griffith Show” on TBS and got to visit with star Don Knotts. On a trip to L.A. after my junior year, I introduced Greenbaum and Knotts to Reagan and watched in awe as the three of them reminisced about their salad days in the industry. In the years after college I continued exploring. I even spent two days on the Warner Bros. lot interviewing Clint Eastwood. He’s a native San Franciscan who was also elected mayor of Carmel in 1986. (His first official act was terminating the planning board that had supported a ban on selling ice cream.) But interviews, books and vacations in postcard destinations weren’t enough to reveal the pull that Reagan described. I had to go through my own California journey to understand. I moved to the West Coast because I started researching and reporting on Reagan.

Visits turned into month-long stays that turned into a full-time residency. You don’t so much move to Los Angeles as your will to leave dissipates.

As a junior at Wake Forest, John Meroney (center) met actor Don Knotts and President Ronald Reagan, among others, during a trip to California.

What I’ve discovered from living here is that everything you’ve heard is true. Odds are your server is an aspiring actor-slash-model. The crime can be as bad as “L.A. Story” portrayed with its “I’ll be your robber” and “open (gun) season on the freeway” scenes. I recognize Elliot Gould’s hippy-dippy neighbors in “The Long Goodbye” because all of us have those kinds of neighbors here. And when I get frustrated at the city I even acknowledge that what Don Draper said on “Mad Men” rings true: “Los Angeles is not what you see in the movies. It’s like Detroit with palm trees.”

After a few years, I could recognize the truth of composer Oscar Levant’s line, “Strip away the phony tinsel of Hollywood and you’ll find the real tinsel underneath.”

Yes, there’s something surreal about California, but there’s magic, too. Part of the reason it exists is because out here, you’re allowed to make it up. In fact, the name of the state is the invention of a fiction writer. In 1510, Ordóñez de Montalvo wrote about “an island called California very near to the region of the Terrestrial Paradise.” Hundreds of years later, poet William Irwin Thompson wrote, “California became the first to discover that it was fantasy that led reality, not the other way around.”

My friend Carol Barbee (’81), showrunner and executive producer of the upcoming Netflix series “Raising Dion,” was born and raised in Concord, North Carolina, and moved to Los Angeles after Wake. She is one of many Demon Deacons here who appreciate this appeal.

“I loved California from the start,” she says. “I felt free here. It has history, but not the kind of history where the way things are normally done feels too difficult to change. California is all about innovation,” she says. “It’s filled with people who left their home towns and states and countries to come do something they couldn’t do back home. It’s nice to get lost here, while you’re trying to figure out who you are and what you have to say.”

What happens here is things that once appeared improbable can come true.

There was a point after I moved here that I thought I had things figured out. While I was reporting on Reagan, I met a former studio chief who announced that my material had the elements of a great documentary. I’ll help you get it made, he said. This seemed like a dream come true.

Soon, Wake Forest alumna Patricia Beauchamp (’94) (writer of “Return to Sender,” a thriller starring Rosamund Pike and Nick Nolte) and I were hard at work on a cinematic documentary about the young Reagan in Hollywood, groundbreaking in what it would reveal about the future president’s stunning transformation from movie star to anti-communist warrior. We were being supported by Hollywood royalty such as Cecil B. DeMille’s granddaughter and Walt Disney’s daughter, who wanted the story told. We were having expensive lunch meetings at the Polo Lounge and in restaurants looking onto the Pacific.

Those lunches went on for seven years. Our lives became like “Groundhog Day.” Except in our version instead of running into “Ned — Ned Ryerson,” the aging ex-studio honcho kept asking about the project, “What is it?” and would then proceed to talk for two hours about the making of “Tootsie.” The final insult was when he encouraged a C-list director to take our script and turn it into something PBS would have passed on for being too “staid.”

No one would have blamed us for packing up and moving to a tranquil life on the Outer Banks, where a commute doesn’t involve a helicopter and news team. But that didn’t even occur to us. It was as if we were saying to California, “I can’t quit you.” But California seems to take devotion as a challenge: “I can not only quit you. I can kill you.” Out here seasons are described in apocalyptic terms. The Biblical disasters such as storms, floods, earthquakes and riots — I’ve learned they’re real here. In November, my mother-in-law’s house in Malibu burned to the ground. And during a rainstorm in February 2018, a neighbor knocked on our front door in the middle of the day to declare, “The street is collapsing!” The 100-year-old water main 10 feet from our house burst, and water was erupting through the asphalt.

What happens here is things that once appeared improbable can come true. I’m a Southern Baptist from Winston-Salem who studied political philosophy at Wake. I moved to Washington, D.C., where I worked for Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, often wore a seersucker suit to the office and socialized at the University Club. But then I headed West. Last year, I married a native Angeleño who is Jewish and went to UC Berkeley. (Half of our wedding party was made up of Demon Deacons, though.) We now live in the Hollywood Hills under the Hollywood sign, just up the road from a Scientology Celebrity Centre. I write for Playboy and am also a producer. California has this kind of impact.

I’ve been here long enough that I can identify with novelist John Gregory Dunne, who was also raised in the East and then moved to Los Angeles. “I sometimes feel an astonishment, an attachment that approaches joy,” he wrote of L.A. in 1978. “I am attached to the way palm trees float and recede down empty avenues, attached to the deceptive perspectives of the pale subtropical light. … I am attached equally to the glories of the place and to its flaws, its faults, its occasional revelations of psychic and physical slippage, its beauties and its betrayals.”

I now recognize the truth of Reagan’s distinction about his adopted state. There are moments for the Wake Foresters who live here that, if we feel ourselves not leaving, not running away, we have to admit that we love this way of life.

John Meroney (’94) is a consulting producer on the Netflix series “ReMastered.” He is a contributing editor for Garden & Gun magazine and author of a forthcoming book about Ronald Reagan in Hollywood. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Republic, Architectural Digest, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the Los Angeles Times. He lives in Los Angeles.