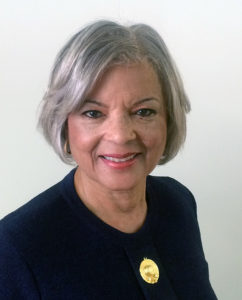

W hen I graduated from Wake Forest in spring 1973, I vowed I would never return to campus.

The journey had been tumultuous, and the struggles overshadowed the periods of grace and joy throughout my four years at the University. However, the art of forgiveness coupled with maturity tends to create a pathway that dissipates unpleasant memories. I returned to the campus in 1983 as a lawyer, worked in the legal counsel’s office, taught in the history department and the law school and retired in 2017. Never say never.

I believe in divine intervention. I was slated to attend Reed College in Portland, Oregon; however, one of my best childhood friends who was a scholar-athlete at Wake Forest reminded me that Reed College did not have a football team, and the distance from school to home in Petersburg, Virginia, might prove problematic.

I believe in divine intervention. I was slated to attend Reed College in Portland, Oregon; however, one of my best childhood friends who was a scholar-athlete at Wake Forest reminded me that Reed College did not have a football team, and the distance from school to home in Petersburg, Virginia, might prove problematic.

I enrolled at Wake Forest in August 1969. Although the tuition was less than $2,000, that was a hearty sum. One of my academic scholarships for $1,000 had not arrived at the treasurer’s office on time, so I was not allowed to register for classes. I thought I would have to return home, and, of course, I was heartbroken. Divine intervention swung through the door again. My mother and I went to see President James Ralph Scales. Upon hearing our plight, he awarded me a scholarship from his deceased daughter’s fund since my great-grandmother was part Cherokee as was his daughter. And the journey began.

When I arrived, there were fewer than 20 black students on campus. We survived by remaining true to our ethnicity. In 1969, Wake Forest sought to attract black women who could compete academically. (There were about 15 black male athletes on campus, and interracial dating was not a healthy endeavor.) The black athletes of my generation graduated from Wake Forest and pursued careers in law, investment banking, medicine, divinity and education. Together, we taught Wake Forest students that successful academic achievements were cross cultural.

During my time at the University, I developed deep friendships, and over the years we have exchanged photographs of children, weddings and grandchildren. I have several Wake Forest friends with whom I have shared Christmas cards every year since 1973.

But from 1969 until 1973 there were battles to fight on all fronts. Fraternities were not our worst enemies. There were professors who vocalized their displeasure about the presence of black students on campus because they felt that genetically we were unable to compete. Those kinds of attitudes made me work harder, and I was determined to graduate with honors.

I decided no one was going to outwork me.

When I was elected homecoming queen, unfortunately the Old Gold & Black student newspaper missed an opportunity to congratulate a Southern Baptist school for crossing the racial divide. There was no headline in the paper to alert the readership that Wake Forest had elected its first black homecoming queen and perhaps entered a new era. But the campus conversation was buzzing with excitement that the University was moving forward in an unexpected way.

The yearbook staff later took a puzzling position. The homecoming photograph in the yearbook shows me with a crown and two black eyes. I am sure the staff was amused, but my family and I were not. Nevertheless, life moved on, and the thrill of winning overshadowed any attempt to take the joy out of my living.

I am honored to be a graduate. Not only do I have 50-year friendships from my Wake Forest days, but I have the confidence of being exceptionally educated, and I am imbued with a Wake Forest sense of a humanitarian dedication.

Beth Hopkins lives in Winston-Salem and spends time rediscovering classical piano compositions, playing tennis and visiting her granddaughters. She received a major award from the Wake Forest School of Law in 2016 with the naming of the pro bono summer stipend in her honor, and she received the William & Mary Law School Association’s 2018 Citizen Lawyer Award, its highest recognition, given annually to a law graduate who has made a lifetime commitment to citizenship and leadership.