The stage has enchanted Hillary Heard Baack (’02) since her parents took her to see a play when she was 5 years old. By age 7, she was performing her first community theatre role as Gretl von Trapp in “The Sound of Music.”

She is deaf, but she was too young to see any obstacle.

Baack has built a career as an actor and writer. This summer, production begins on a movie she has written about the adult life of Helen Keller, a deaf and blind American icon. Baack will star in the film and make her feature directing debut.

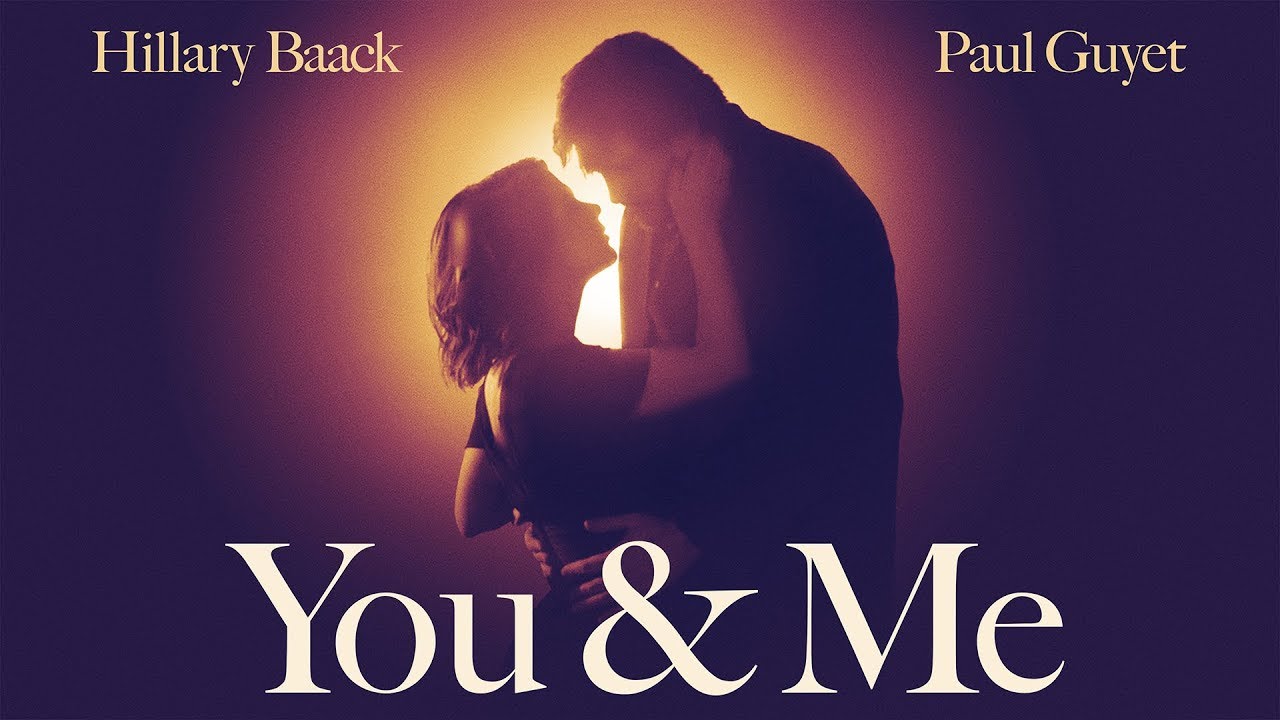

Baack wrote and performed her own one-woman show in New York. She has appeared in short films, TV episodes and full-length features. She starred in “You & Me,” a 2018 romantic comedy she co-wrote with her husband, Alexander Baack, a director and producer. They live in Hudson, New York, with their sons, ages 2, 10 and 14.

Wake Forest Magazine talked with her about her life and career. These excerpts have been edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you become deaf?

A lot of things went wrong right after I was born. I lost my hearing when I was 1 month old. I was given an antibiotic, which saved my life, so it was a good thing, but one of the side effects was my hearing. I had a lot of other things going on, so by the time I came home, it wasn’t like they were looking for hearing loss. I was diagnosed (as deaf) when I was 3.

From "You & Me"

Even the things that I lost have been a huge part of shaping and informing who I am and probably made me a better version of myself. Because there was a lot of medical stuff I went through, I was always feeling so grateful for what I had. That doesn’t mean I didn’t have days when I was frustrated, but I think when you’re aware of what you don’t have, you can also become more aware of what you do have.

It’s been an interesting part of shaping even my path as an actor, too, because I’m so attuned to people, their behavior, being on the outside observing human nature and stories.

You were mainstreamed in school with all students. How did that influence you?

My lip-reading skill became stronger and stronger because I used it all the time, and I feel grateful that I’m able to communicate so well with hearing people. And because of being mainstreamed and having speech therapy, I was able to work on my speech. The shadow side to that was working really, really hard in a way that’s different than if you’re watching sign language. And being the only one.

(Mainstreaming is) different for every child, for every family, for the time in which you’re living, as well. For me what it looked like was sitting in the front of the classroom. My teachers (in Orlando, Florida) knew that I needed to lip-read. By the time I was in high school, I had note-takers because I couldn’t take notes and lip-read, so I had that support. At Wake, I had note-takers. I would have a meeting with each professor to explain my situation. There were a few times when I had an interpreter.

What drew you to acting?

I was so young, it was not something I could articulate why I wanted to be up there on stage. There’s something so thrilling and moving about watching performers. I was drawn to taking this moment to learn something about life, to be present and really think about those feelings or those experiences, celebrate them, honor them. It was so freeing and fun, and it was this really expressive and safe place. And the relationship between yourself and the audience is an exciting, powerful thing.

You have said you became self-conscious as a teenager and doubted you could pursue acting. What changed?

I remember a conversation I had as a freshman with (associate teaching professor) John E.R. Friedenberg (’81, P ’05), whom we all called JERF. He was the one who put the idea in my head that I could be a theatre major and possibly have a career. I think about my theatre professors, and all of them were encouraging. My time at Wake was such a wonderful time to gain tools and also the belief and confidence that maybe I could keep doing this in my life.

What has been your favorite role?

At Wake, I got to play Sarah in “Children of a Lesser God,” and that was incredibly intense and rewarding and exciting.

Was Marlee Matlin, the deaf actress who won an Oscar as Sarah in “Children of a Lesser God,” an inspiration?

For sure, she was one of the huge affirmations and inspirations for me that it was possible.

Hillary Baack (’02) and Lee Connelly (’02) in “Children of a Lesser God” at Wake Forest

What did you do after graduating with a double-major in theatre and English?

I did a theatre program in Los Angeles. I got certified to teach English as a second language, and I worked with deaf children in Barcelona (Spain). After that I went to New York. I got a job in disability services support, my day job, and I jumped into theatre acting classes at the Barrow Group (Performing Arts Training Program). The first role I got in New York was a reading in the theatre. The next thing I did was my (one-woman) show. About a year after that I got a role on Law & Order. (Television) was very different, very exciting and made me hungry for more.

What brought you to write about Helen Keller?

I revisited the (1962) film “The Miracle Worker” (with Patty Duke as Keller) when I was an adult. I had watched it as a child and had seen plays of it. I’ve always felt as a deaf woman some sort of connection to her, and I’m learning so many women and girls have felt a connection to her, whether they have a disability or not. I thought, “Well, what did she do? How long did she live?”

Helen Keller on her graduation cum laude from Radcliffe College in 1904. She was the first blind and deaf person to earn a bachelor's degree.

I immediately got a book about her life, and the whole time my mind was blown. I could not believe what an incredible life she lived, could not believe I didn’t know about it. I have to tell this story. (Keller was the first deaf and blind person to earn a bachelor’s degree, graduating cum laude in 1904 from Radcliffe College, and lived a full life as an author and activist, including co-founding the American Civil Liberties Union.)

It’s been something I’ve been working on and off with for many years, and in the past year, things have really started happening. We (the Baacks’ Force Studios, which is raising money for the film) have the musician Markéta Irglová signed on to do our music. (She co-wrote “Falling Slowly,” which won the 2008 Oscar for best original song, in the indie film “Once.”) I feel very excited to be telling the story from my point of view.

What advice would you give a deaf person considering acting?

Find the community of other deaf artists. There’s more and more support for each other because the culture is giving a little more attention to minority voices. Go to (acting) class, find a community and start to make your own work. If you’re not a writer, find a deaf writer and work with them. Don’t wait around for auditions to come to you. Ask for an opportunity to be seen in roles that are not deaf. Why can’t this person be deaf? A lot of times it can make the story that much more fascinating. (When I started) it was a lot harder to persuade someone to consider a deaf actor, and I do see that’s changing. That’s very inspiring and hopeful.

Some of Hillary Baack’s work:

Feature films: “The East,” a 2013 spy thriller, “Always Chasing Love,” a 2016 crime drama, and “Sound of Metal” in 2019 about a heavy-metal drummer.

TV: “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” “Switched at Birth,” “Little America,” now in post-production.