If you ever saw Kunal Premnarayen (’00) run the baseline when he was playing on the Wake Forest tennis team, you would never have known that he was born with bilateral clubfoot.

He never told teammates or friends about the birth defect that likely would have left him unable to walk, much less run, had he not been treated as a baby. “Some of my friends are going to be surprised,” he said. “I wasn’t putting it under the mat, but I never appreciated how lucky I was until I got a little older.”

Clubfoot causes one or both feet to turn inward and upward and is one of the most common birth defects in the world. About 175,000 children, or 1 in 800, are born with clubfoot every year. Left untreated, it’s a leading cause of physical disability.

It’s rarely seen in adults in the United States or Europe, thanks to early treatment. Olympic figure-skating champion Kristi Yamaguchi, soccer star Mia Hamm and NFL Hall of Fame quarterback Troy Aikman were born with clubfoot, but, like Premnarayen, were treated as babies.

A mother and her child wait for treatment at a clinic in Uganda. Photos courtesy of MiracleFeet.

But in developing countries, only about 15% of children born with clubfoot are treated. In India, where Premnarayen grew up, only about 30% of the estimated 35,000 children born with clubfoot every year are treated. He finds it especially frustrating because clubfoot can be corrected for about $500 per child.

“My heart breaks when I see people in the streets with their feet inverted and disabled,” said Premnarayen, who returned to India a few years after graduating and lives in Mumbai. “The difference between them and me is less than $500. Five-hundred dollars between living a normal life and living with a disability. I’m blessed to have the ability to make a difference.”

He’s on a mission to ensure that no child is disabled because of clubfoot. He serves on the U.S. board of MiracleFeet, the largest global organization solely focused on treating clubfoot. Based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, the nonprofit partners with local health care providers in 26 countries in Africa, Asia and South America to increase awareness and access to low-cost treatments. MiracleFeet has treated more than 40,000 children since it was founded in 2010.

Kunal Premnarayen and his daughter, Samara, visit with a mother and her son in their home; the son was treated at one of the clinics that Premnarayen and his parents founded in India.

“I see disabled children in the road and the first thing that goes through my mind is, ‘if I don’t help them, who will?’ ”

Premnarayen and his parents founded MiracleFeet India, an affiliated but separate nonprofit. MiracleFeet India has treated about 16,000 children through a network of 50 clinics, primarily in public hospitals. Premnarayen has aggressive goals to double the number of clinics in the next nine months and to open more than 500 in the next five years. (Premnarayen’s father, Deepak, is chair of the board of directors of MiracleFeet India.)

“There is no stronger advocate for children born with clubfoot than Kunal,” said Chesca Collordeo-Mansfeld, executive director of MiracleFeet. “He knows how lucky he was — and how different life could have been for him if his parents hadn’t been able to seek out the best possible treatment. He has wholeheartedly committed himself to ensuring every child born with clubfoot in India can walk, run and play, just like he has been able to do.”

Treating clubfoot: Doctors use a series of casts to realign the feet.<br />

Another Wake Forest graduate, Lindsey Graham Freeze (’04), is director of marketing and communications for MiracleFeet in Chapel Hill. She and Premnarayen have never meet, but their joint cause joins two Deacons 8,000 miles apart.

Freeze spent 15 years in communications in global development and health care before joining MiracleFeet. Through her travels around the world, she has seen the consequences of children living with physical disabilities in some of the world’s poorest countries.

“Here’s an issue (clubfoot) that could be wiped out for most of the planet with very little infrastructure,” she says. “You can’t guarantee that life is going to be easy for anyone anywhere, but you can give a child equity with their peers and mobility for the rest of their life.”

A series of braces help keep the feet in the proper position.

Premnarayen knows his life would have turned out much differently if his parents hadn’t taken him to an orthopedic surgeon in Mumbai when he was 9 days old. The doctor realigned his feet using casts, braces, physical therapy and corrective shoes that he wore until he was 6.

He started playing tennis while he was still in steel shoes, following in the footsteps of his grandfather, who played in the French Open and at Wimbledon and on India’s Davis Cup team. Premnarayen became the fifth ranked junior tennis player in India before coming to the United States to attend high school in Florida and improve his game.

Then-tennis coach Ian Crookenden recruited Premnarayen to Wake Forest. He played on the tennis team for two years, then took a year off to play tennis full-time. He returned to Wake Forest and graduated with a major in communication and a minor in international studies.

“Here was this Indian kid from Bombay in a Southern school,” he said of his introduction to Wake Forest when he was the only student from India. “It shaped me as a person. I made some lifelong friends. I took some amazing liberal arts and international politics courses. I was on the tennis team and in a fraternity (Sigma Phi Epsilon). The entire college experience left me with some lovely memories.”

Mothers wait with their children at the Wadia Clinic in Mumbai, the first of the clinics across India that Premnarayen's family supported.

After graduating, he worked in Atlanta for a few years and then moved back to Mumbai, where he is group CEO and board member of ICS Group, a real estate company founded by his father that operates in India and South Africa.

He never gave much thought to clubfoot. When he got married in 2011, he and his wife, Kavita, asked friends to make a donation to a nonprofit in lieu of wedding gifts. Kavita discovered MiracleFeet and their wedding guests donated more than $10,000.

That’s when he realized that he had a special obligation because of his background to help children born with clubfoot. Clubfoot still carries a social stigma in India; some parents consider it a curse on the baby or mother and may abandon their child. Many parents don’t have the knowledge or money to seek treatment or lack transportation to a doctor. Children not treated are likely to be shunned, be unable to attend school or find work, and face a life of poverty, neglect and abuse.

“If you are in rural India and your child is born with clubfoot, it’s bad because parents want their children to help work,” Premnarayen said. “If you have a girl with clubfoot, it’s very tough. We are treating a baby who was buried alive; other villagers found her. It’s shocking, but it happens.”

Clubfoot is most often treated today using the Ponseti method. Developed by an Iowa doctor in the 1950s, it replaced surgery as the preferred treatment method in the 2000s. Health care workers use a series of plaster casts to gradually move the foot into the correct position over five to eight weeks. Once the foot is properly aligned, a brace is worn for several years to maintain the position.

Premnarayen is committed to giving children born with clubfoot the same opportunity that he’s had to live an active life. “There are so many problems, big problems, in the world today. Clubfoot is a problem that’s easily curable with a limited amount of funding. Think about the impact that can have on a child’s life. It should not be a disability anywhere in the world in 10 years.”

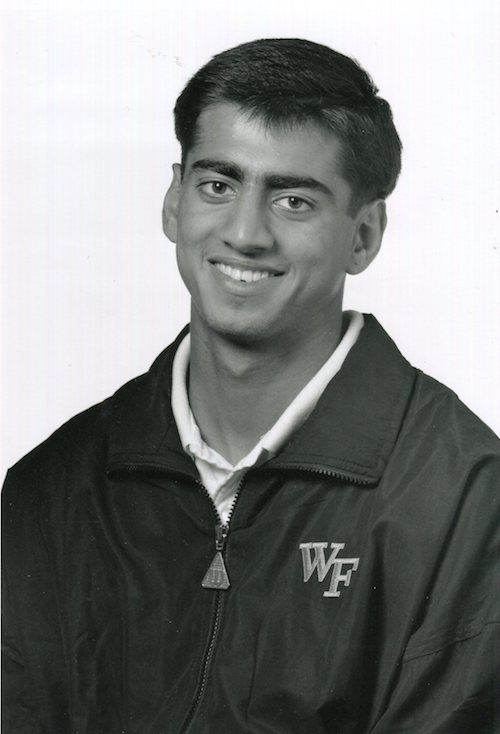

Kunal Premnarayen ('00) when he was a Wake Forest tennis player.