(Jump to profile by clicking name)

- In Praise of the Unweird

- At the last minute, Page Laughlin discovered artists who modeled their lives for her.

- The Keyboard Code

- Music Professor Peter Kairoff’ says his world opened thanks to a beat-up piano.

- There’s Lucy!

- How Mary Wayne-Thomas, professor of costume design, found her way to the theatre.

- Shock and Awe

- Art Professor David Finn learned early on that art can appear deceptively simple.

- Beach Boys to Bach

- How Dan Locklair, composer-in-residence, discovered magic in music.

- A Perfect Blend of Art and History

- Bernadine Barnes found her forte through a series of fortuitous roadblocks.

- Ballet was the Ticket

- Nina Lucas was a tiny dancer when she knew where her dreams would lead her.

- Bargain Trombone

- Stewart Carter began playing music on his dad’s trombone because it was already in the house.

- Improv Hippies

- Theatre Professor Sharon Andrews and her theatre gang ventured west to transform the arts.

- A Springsteen Connection

- David Lubin learned from a mentor who also worked for — and taught — the Boss.

- Begging Worked

- How entreaties and a cinematic trip to Norway helped Teresa Radomski score piano lessons.

- A Cello to Chicago

- Elizabeth Clendinning persuaded her mother to ship the instrument, and soon the professor was enmeshed in world music.

In Praise of the Unweird

At the last minute, Page Laughlin discovered artists who modeled their lives for her.

Page Laughlin | Harold W. Tribble Professor, painting

Page Laughlin received her undergraduate degree from the University of Virginia (Phi Beta Kappa) and her MFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design. She has exhibited in galleries across the country, and her paintings are in private and public collections, including the North Carolina Museum of Art, The Mint Museum in Charlotte, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA) in Winston-Salem.

It was my senior year — undergraduate at the University of Virginia — and I was going to law school or medical school. I took a studio art course for the first time because I had time. I try to tell students, “Do this earlier.” I went into the class, and the teacher changed my life direction radically.

I think the aha aspect of it was, it was the first time I had really met and worked with professional artists. I’d gone to museums, but those artists were dead, or I didn’t know them. I’d had whatever art class you get in middle school and high school, but they were invariably (taught by) somebody’s mother, or they were the math teacher teaching art because it was considered just an add-on spice. I walked into a course taught by professional artists who — their practice, their living, their commitment — was to making art. I realized that they were in some ways the most engaged and intelligent people I’d worked with as an undergraduate. They showed me that making art is a way of exploring the world.

If you’re a person with a lot of curiosity, it’s a very good place to operate within. And they weren’t weird. They hadn’t cut off their ears. They weren’t zany. They were highly intelligent and creative. They were talking about politics and the environment and philosophy and the color theory and science and observation and quantum physics and studio class. I found myself spending all my time in the studio. So, I can locate the shift. You could say it wasn’t so much aha, but maybe it was a shift where I thought, “I need to explore this. I need to find out what this is all about.”

There are no guarantees in the art world at all. (After graduation) I picked up and moved to San Francisco, because it was an area of creatives then and now. It was as far away from my traditional upbringing as it could be. … My parents were like, “Oh, you need to go into advertising. You want to be creative, let’s go into advertising.” Then I think they held their breath for about six months, thinking I would change my mind, and I didn’t.

I was able to just get a job that paid rent. I painted in my attic. … I finally said to my parents, “I’m doing this. I’m not asking you to be financially supportive. You can choose to be supportive or not, but I’m going to do it,” and that was it. I think (there were) tears and probably very impassioned hanging up the phone. This is what I was saying, “I’m going to go to graduate school.” My parents called back and said, “OK. Make a list of the best graduate programs in the United States.” Not that they would pay for it, but they said, “OK,” — like “If you’re going to do it, be the best you can be. Whatever you do, do it well.”

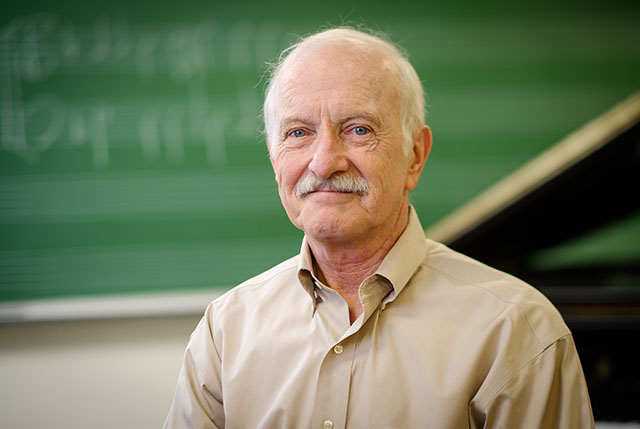

The Keyboard Code

Peter Kairoff’s world opened with a beat-up piano.

Peter Kairoff | chair and professor of music

Peter Kairoff has performed as a pianist and harpsichordist around the world and has been described as one of America’s finest keyboard performers. He joined the faculty in 1988 and has directed Wake Forest’s Casa Artom program in Venice for 25 years. He has published eight CD recordings, including works of Bach, Schubert and late-19th century American composers. A native of Los Angeles, he attended the University of California San Diego intending to become a doctor, but he later earned his master’s and doctoral degrees in music performance from the University of Southern California.

I was the last of five kids, and by the time I was 13, I was the only child at home. My father, who died before I got to know him, had been a Russian opera singer. (Kairoff’s father emigrated to the United States in the 1920s; he died a few months after Peter was born.) My mother was a single mom, and we were of very limited means, but she bought an old, beat-up church piano for $30 and brought it home.

She got the local neighborhood teacher –to teach me. She said, “This dot on the page means this key on the keyboard,” and off we went. I remember saying to her, “I think you’ve just opened the whole world to me.” I think I scared her. To me the aha moment was day one, minute one. This is amazing. I get it. You do this and then that, and I could somehow, already as a little kid, extrapolate, wow, if I do that, then pretty soon I’ll be able to do all that other stuff.

She got the local neighborhood teacher –to teach me. She said, “This dot on the page means this key on the keyboard,” and off we went. I remember saying to her, “I think you’ve just opened the whole world to me.” I think I scared her. To me the aha moment was day one, minute one. This is amazing. I get it. You do this and then that, and I could somehow, already as a little kid, extrapolate, wow, if I do that, then pretty soon I’ll be able to do all that other stuff.

My mother would go to the public library and check out classical LPs. I still remember how they sounded on my 10-year-old record player. That was an education in itself. Somehow, I don’t know how she did it, she found an old baby grand piano that she got someone to give us. It was a name you’ve never heard of, but what an amazing thing. We were in a tiny, one-bedroom apartment with a baby grand piano taking over the whole living room.

I went to a pre-college music program at the University of Southern California. And you talk about aha moments! My piano lessons were next door to the room where Jascha Heifetz, the great god of violin, taught. Gregor Piatigorsky, the great Russian cellist that people would flock to from all over the world to study with, was on the other side. I had a sense of these mythic people, this whole world of European emigrés coming to Los Angeles to make beautiful music in the sunshine. I was like a kid with his nose pressed against the glass.

I still never intended to make music my career because I started late. I presumed that was for other people, the Arthur Rubinsteins of the world. At the end of college, something in me said don’t go to med school yet; take a year off. I got a job accompanying at the San Diego Opera as a rehearsal pianist. The first rehearsal, in walks Beverly Sills, and she sits down on the bench next to me. She starts to sing, and I practically fell off the bench. I’d never heard anything like that. It was musically thrilling, but it was also a realization that maybe I can make a living playing the piano.

One of the reasons I love teaching at Wake Forest is that so many of my students, as gifted are they are, are doing a thousand other things and majoring in two or three other areas. I like to think I’m keeping their love of music going. And, occasionally, some — even a few pre-meds — switch and go into music and are professional musicians now.

I realized early on that teaching and performing are part of the same thing. When I teach and when I perform, I’m revealing the inner workings of a great work of art that I love deeply. I often tell my students that music picks up where words leave off. It has a way of expressing things that can’t otherwise be expressed. I feel immensely lucky to be able to live this dream that little 13-year-old me could only have guessed at.

There’s Lucy

How Mary Wayne-Thomas found her way to the theatre.

Mary Wayne-Thomas | professor of scenic and costume design; F.M. Kirby Family Faculty Fellow

Mary Wayne-Thomas has designed sets for 49 productions and costumes for 76 productions since coming to Wake Forest in 1980. She has also designed sets and costumes for numerous theatre companies, including the Little Theatre of Winston-Salem and the Attic Theatre in Los Angeles. She has done a bit of everything behind the scenes — as a tailor, prop master and master carpenter — for productions around the country, including the North Carolina Shakespeare Festival, Alabama Shakespeare Festival and Utah Shakespeare Festival.

I grew up in a small town (Philipsburg, Pennsylvania), but it was very close to Penn State, and we would occasionally see plays there. There was a community theatre in town, and my mother did costumes for the theatre. There’s a story in my family which I don’t remember because I was probably 3. My oldest sister was in a play in high school, “Bertha the Beautiful Typewriter Girl.” She was playing Bertha, and when she walked onstage, I yelled, “There’s Lucy!” That was my introduction to theatre.

In high school, I’d done some backstage work. When I was a senior I was cast in “Inherit the Wind” in a small role. The play was canceled because of (a complaint from) one parent. Those of us who know the play felt it was not disrespectful of religion. At that point, I realized that theatre is a powerful thing. And that stuck with me.

When I started college (Penn State), I was a math major. One night, I went to see a play, “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” and I thought, “I want to be a theatre major.” It’s a powerful, moving and heart-wrenching play. It was extraordinarily well done. I was mesmerized. I wanted to be part of a world where telling a story, and telling it well, can move people and perhaps change their minds.

One of the reasons I chose Ohio State (for graduate school) was because I could do costuming. That’s where I really started studying costume design. I knew how to sew but not necessarily how you construct a costume. I came to Wake Forest because the job was both scenic and costume design in a relatively new theatre. (The theatre wing of the Scales Fine Arts Center opened in 1976.)

There are a number of shows that I’ve designed twice, but they’re never the same. You’re working with different actors. You’re performing in a different time. But the bottom line is — and I always tell my students this — your goal is to help the audience understand the play.

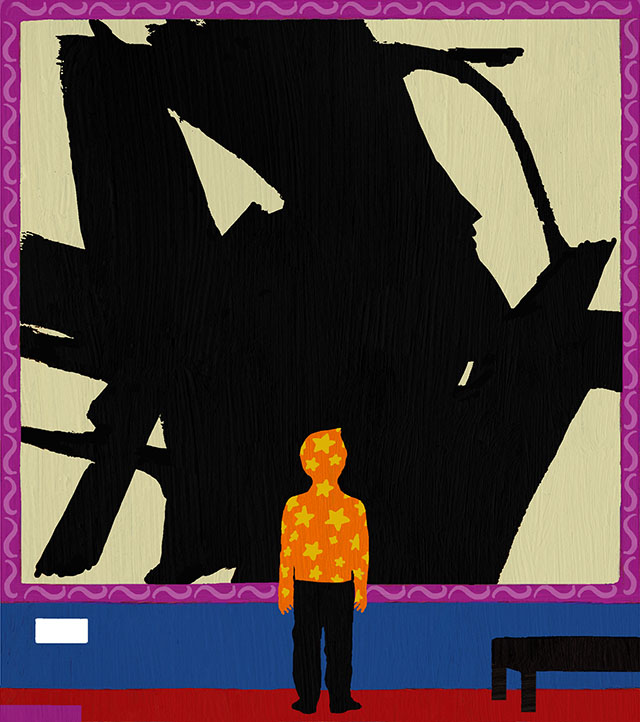

Shock and Awe

Inspired by abstract expressionism, David Finn learned early on that art can appear deceptively simple.

David Finn | professor of art

David Finn has taught sculpture at Wake Forest since 1987 and has presented solo exhibits in New York, London, Milan, Hong Kong and elsewhere. He has received grants and fellowships from, among others, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the North Carolina Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. He began making “Newspaper Children,” child-sized bodies from newspapers placed in evocative installations, in 1982. He has worked in plastics, ceramics, wood, steel, wax and stone.

He describes his work as primarily project-based and tied to a concept rather than a medium. He is interested in socially engaged art, funeral rituals and memorials, carving, fermentation and public art and design. His “Transforming Race/Big Tent” public project, ongoing since 2011, connects art students and local high school students to discuss race and diversity and produce artwork.

I saw a painting by Franz Kline (1910-1962) when I was 18 that was one of those moments when I saw something that I’d never seen before, didn’t anticipate. It was really kind of shocking and awe-inspiring. I saw this in a museum (at Cornell University).

The thing that was so amazing to me was the encounter with the physical presence of this large painting, which seems to be really so spontaneous, just having such a physical impact with its scale and with its gesture.

The thing that was so amazing to me was the encounter with the physical presence of this large painting, which seems to be really so spontaneous, just having such a physical impact with its scale and with its gesture.

I hadn’t had a lot of exposure to that kind of art, which is Abstract Expressionism, so it was a completely new experience. Lots of people have that kind of art experience, right? But what happened to me was I said — and I’ve heard many students say something like this — “That can’t be that hard to make, and I would really like to have a painting like that.” And that’s what got me started, to try to recreate that sense of awe and make something that could inspire that. But, of course, you know what? It’s really hard. That’s the punchline, that I’ve spent my entire life to try to create that, because it’s very elusive. I think it helps (students) get it that it’s deceptively simple.

I also used to read poetry in class, which is just, “Anybody can use these words to make something up.” They understand that having the experience of trying to make something is extremely valuable because it teaches you more about those things that you love. That’s something that you can’t get just by writing about it or analyzing it. You begin to understand, by actually writing poetry, by actually putting a brush onto canvas, those physical acts are important to understand what really can transform somebody. It actually changes the way we see things, and when you’re that age, you’re looking for that.

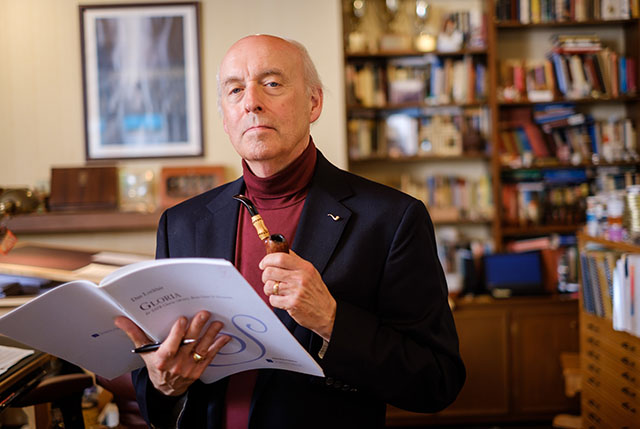

Beach Boys to Bach

Composer Dan Locklair found magic in music.

Dan Locklair | professor of music & composer-in-residence

Dan Locklair, who joined the faculty in 1982, has composed orchestral, chamber, solo and choral music that has been performed throughout the United States and around the world by, among others, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, Slovak National Symphony Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony, Kansas City Symphony, North Carolina Symphony and Winston-Salem Symphony. “The Peace may be exchanged,” a movement from “Rubrics,” one of the most frequently performed pieces of late-20th century American organ music, was performed at the funerals of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

I started studying the piano at age 6 with the organist at my home church and began playing the trombone at age 10, eventually playing in the Charlotte Symphony Youth Orchestra. In elementary school, I remember hearing the Charlotte Symphony Orchestra; that was magical, because I had never heard an orchestra. The symphony later had a competition where young people could audition to play the glockenspiel in “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” from Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker.” That was my first time onstage.

By the time I was 14, I was composing and had my first church organist post. I was 16 when my high school orchestra and choral directors performed my first pieces. I was conducting and writing church music, but I also had an interest in the Beach Boys and the Beatles. But my passion was listening to classical music. We were members of Caldwell Presbyterian Church (in Charlotte), and I loved choral music and the organ, what Mozart called “the king of instruments.” You really do learn what you might love when you’re in the midst of hearing it. It’s simply the sound of what a well-trained choir sounds like or what a hymn or Bach played well sounds like played on the organ. You can never tell what impact that will have on a young mind.

I was fortunate to have an uncle, Wriston Locklair (a music critic and an administrator at The Juilliard School), who was an avid music lover. Even as a child, we would exchange letters, and he would send me LP recordings of Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, Handel, Tchaikovsky. When I moved to New York, we went to many world premieres and concerts together.

Some aha moments you can remember exactly when they hit; others take place over a longer stretch of time. I had incredible teachers (at Mars Hill College, Eastman School of Music and School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary) with high standards who taught that unless you were the best that you could possibly be, you would not be able to compete. I wanted to become the finest composer that I could be and the finest organist that I could be.

At Union, I started to craft my pieces with the smallest number of musical ideas and to think of a music composition as a journey. It has to have a beginning, go somewhere, reach a destination and end. Else the journey doesn’t make any sense. That changed my life as a composer.

Nadia Boulanger, the teacher of Aaron Copland, once said: “Do not take up music unless you would rather die than not do so.” For me, that has been a guiding credo.

A Perfect Blend of Art and History

Bernadine Barnes found her forte through a series of fortuitous roadblocks.

Bernadine Barnes | chair and professor of art

Bernadine Barnes teaches the Renaissance and Baroque periods. She is particularly interested in how artists direct their works toward specific types of viewers or buyers and how critics articulate audience expectations. Her book, “Michelangelo and the Viewer in his Time,” shows how he considered settings and viewers in such works as the David and the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Her other interests include representations of women in the Renaissance, artists as entrepreneurs and cultural encounters in the Early Modern Mediterranean.

I went to the University of Illinois (at Urbana-Champaign), and I was in the College of Liberal Arts (& Sciences) there, but I’d always had an interest in art, and I thought I wanted to become an artist. I wasn’t able to declare a major in art. You really had to apply to the School of Fine (and Applied) Arts at the University of Illinois. I had to do a portfolio, and I was always scared to do it, so I stayed in liberal arts, and I’m really glad I did because I got to study psychology and anthropology and literature and languages. But I kept doing art and making art, taking classes in art, and eventually I had enough training in art to be able to teach it in high school or junior high. I had a terrible experience with my student teaching. I found out I had not much patience for middle school students. It wasn’t fun.

I finished my student teaching in the middle of the year, and I didn’t know what to do because it would be impossible to get a job. A professor of mine suggested, “Why don’t you take a course in art history? You might like it.” And I did. I realized that was really what I wanted to do (and) tapped skills, interests that I had about writing and cultural history and the way literature deals with meaning and interpretations. And the study of religions was always important to me, and that still is important to me, so it was the perfect kind of liberal arts study for me.

I was always fascinated with people like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. When I was a kid, I actually wrote a paper about Michelangelo that my mother saved. She hardly saved anything, but she saved that and gave it to me. I think I’ve always just been really interested in these kinds of multifaceted, pretty heroic people.

I have a strong but unfocused ability to do art, to make things. That has absolutely influenced how I think about art history. But most of my publications are actually more about how people react to art, how they see it and criticize it and think about it. That’s a really important thing, too, that when you are an artist you are trying to get something across to somebody else. What they do with it is something else maybe that you can’t control. It’s a really interesting communication process.

Ballet was the Ticket

Nina Lucas was a tiny dancer when she knew where her dreams would lead her.

Nina Lucas | chair of theatre and dance department; professor of dance

Nina Lucas has been on the faculty since 1996, teaching classes that include modern and jazz dance; movement for men; history of dance; performance and choreography; multi-ethnic dance; and African American choreography. She is the artistic director of the University’s Dance Company. She has a bachelor’s degree in dance performance from The Ohio State University and an MFA in performance and education from the University of California Los Angeles. She has trained at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center, Phil Black Dance Studio and Martha Graham’s school in New York City. In 2001, she received the University’s Reid-Doyle Prize for Excellence in Teaching.

We were army brats while my father was in the military. We were stationed in Fayetteville (North Carolina). My mother put my sister and me in a dance class, and that was it. … I must have been between 4 and 6, and I remember the dance class, the smell of the studio, the compliments from the teacher and just how excited I was about being in that class. Once we transferred from North Carolina to Ohio, I took two classes at Dayton Ballet School, and the rest is history. I knew for the rest of my life at a young age that I was going to be involved in the arts, specifically as a dancer.

I knew I was going to college to major in dance. I remember my dad said, “Are you sure?” And I was like, “Yes.” “Don’t you want to go into accounting?” I was, “No, God, no. I’m terrible at that. No, Dad. Thanks, Dad. … I promise to make a career out of this.” And I look back, and I have. It’s been a part of my life forever.

I knew I was going to college to major in dance. I remember my dad said, “Are you sure?” And I was like, “Yes.” “Don’t you want to go into accounting?” I was, “No, God, no. I’m terrible at that. No, Dad. Thanks, Dad. … I promise to make a career out of this.” And I look back, and I have. It’s been a part of my life forever.

I started in ballet, and then I was introduced to modern dance in the ’70s. It was creative movement, and I loved the fact I could be more expressive and either mimic the lyrics of the song or make up stories through movement, but technique was really important. … I gravitated toward contemporary. And partly because it was really hard for African Americans in that time to be involved in ballet because you had to have that svelte, lean body, and I mean I was a tiny person, but I had quads and glutes. Not that I couldn’t work that technique. It just was a kind of stereotype against African American dancers at the time that you weren’t built or designed for this.

My teacher in Ohio brought in a black ballet dancer from DTH (Dance Theatre of Harlem). That (class) was hard, but having someone who looked like me and moved like me teach us a class and help us understand the technique and work with us one-on-one was really a rich experience and broke down those barriers with what you couldn’t do. I think my parents being an integrated couple, my teacher — everyone I was surrounded by — was, “Break that ceiling. Break that ceiling,” really encouraging us to move forward.

I love ballet to this day.

Bargain Trombone

Music Professor Stewart Carter began playing music on his dad’s trombone because it was already in the house.

Stewart Carter | professor of music; chair, East Asian languages

Stewart Carter (P ’02), who joined the faculty in 1982, teaches music history and music theory and directs the instrumental component of the Collegium Musicum, an ensemble performing music from the medieval, Renaissance and Baroque eras. He studies music of the 17th century and the history of brass instruments. He became interested in Chinese musical instruments a decade ago and has traveled several times to China to meet with performers, conductors and instrument makers.

I grew up in a small town in southern Kansas. I started playing the trombone at an early age, fifth or sixth grade, because my father owned one. I don’t think he had played it after college, but he had kept it. He may have trotted it out and blown a few notes when he was trying to get me interested. Part of the reason was economics; we already owned a trombone, so he didn’t have to buy an instrument.

I had a very inspirational music teacher (in high school). He gave every student in the instrumental music program a private lesson every week. That got me thinking about music in a serious way, and I decided I wanted to be a high school band director.

One of my band directors in college (University of Kansas) was a mentor. He saw brass ensembles as more than just a sideline. I joined the ensemble, and we went on tour, mostly in Kansas. (At graduate school at the University of Illinois), I was classified 1A in the (Vietnam War) draft and received an induction notice. I got my draft board to defer my induction until I could audition for The United States Army Band.

I spent three years (with the Army Band) instead of three years in Vietnam or wherever they might’ve sent me. I played a lot of concerts and funerals in Arlington (National Cemetery) for soldiers who had died in Vietnam. It was just one right after the other some days. That part of it was rather depressing.

I taught public school general music for two years and decided I wanted to teach early music — from the Renaissance, medieval and Baroque eras — and the history of musical instruments, and the place to do that was in a college. Later I became interested in Chinese musical instruments. A student, Cheng “Nick” Liu (’13), and I went to China (in 2011) so that we could research Chinese folk orchestras. The orchestra uses Chinese instruments, but it’s an ensemble that combines Eastern and Western elements and looks very much like a Western-style orchestra.

I tell students you should do it (pursue a career in music) if you have to do it and you wouldn’t be happy doing anything else.

Improv Hippies

Sharon Andrews and her theatre gang ventured west to transform the arts.

Sharon Andrews | professor of theatre, directing and acting

Sharon Andrews started teaching at Wake Forest in 1994 and directs annually for the University Theatre. She also directs and acts in other theatres and helps develop new plays. She was a founding member of Theatreworks at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs, returning there to star in Henrik Ibsen’s “Ghosts” on the theatre’s 40th anniversary in 2015.

I knew I wanted to be a teacher before I knew that I was going to be a theatre person. In the first grade, I was Jill in “Jack and Jill,” but I got strep throat and couldn’t go on. I was sorely disappointed. In seventh grade, I went to a UNCG (UNC-Greensboro) lab school. I auditioned for the school operetta, “The Flying Dutchman,” and was shocked when cast in the lead role. That was a moment when I thought, “Maybe this is something that I can do.”

So all through junior high and high school, I did lots of shows and community theatre. When it came time for college, we were not a wealthy family, so I went to UNCG to major in sociology and become a social worker. But I kept auditioning for shows and was so invested in the world of theatre. I transferred to Chapel Hill (University of North Carolina) and decided to go for it, to major in theatre.

So all through junior high and high school, I did lots of shows and community theatre. When it came time for college, we were not a wealthy family, so I went to UNCG to major in sociology and become a social worker. But I kept auditioning for shows and was so invested in the world of theatre. I transferred to Chapel Hill (University of North Carolina) and decided to go for it, to major in theatre.

A student a year ahead of me, Lewis Black, who is a well-known comedian now, hung notices on campus trees about forming a theatre company. A bunch of us signed up. We improvised ideas about growing up in the ’50s, and Lewis would take our improvisations home and write them up and come back the next night, and we would work on it until we had created a whole show. We performed at the student center, and it was a huge success. We went on tour, and one of the places we came was Wake Forest when the theatre was in the library (Z. Smith Reynolds Library). That’s when I first met (now retired Professor of Theatre) Harold Tedford (P ’83, ’85, ’90).

When we first started in Chapel Hill, the group was called Feast Family. Then the Manson family murders happened, and we decided that wasn’t a good thing to call ourselves. Then we moved, all 25 of us, to Colorado Springs and called ourselves Homestead Arts Theatre. We had heard there was a little log cabin theatre for sale there, and Lewis (and others) went out to look at it. The city wouldn’t let us open because of code (violations), so we wound up doing our shows in a park and a high school and a prison. We were a bunch of hippies coming to transform the arts in the town. We were passionate about theatre and willing to wait tables and do whatever we had to do. We were of the era where we thought, “Do what you love, and food will come.”

After Homestead Arts, I became a founding member of Theatreworks and taught acting for several years at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs. My life circled back to Winston-Salem, and I felt like I had hit a gold mine when I was hired to teach at Wake Forest.

I love being part of telling a story. Somewhere along the line, I learned that theatre was born out of religious ritual. It has always felt to me that theatre does have a sacred purpose, a connection between human beings’ desire and need to tell our stories.

A Springsteen Connection

David Lubin learned from a mentor who also worked for — and taught — the Boss.

David Lubin | Charlotte C. Weber professor of art

David Lubin’s interests range across an academic landscape that focuses on American visual art, film history, popular culture, music, World War I and more. He studied filmmaking at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts while reviewing music for Rolling Stone magazine, followed by a Ph.D. in American Studies from Yale University. His books range from “Act of Portrayal: Eakins, Sargent, James” to “Titanic,” a cultural-studies analysis of the blockbuster film, to “Grand Illusions: American Art and the First World War.” He received the Smithsonian Institution’s Charles C. Eldredge Prize for distinguished scholarship in American art for his book “Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images.” He was a visiting professor at Oxford University and received a Guggenheim Fellowship.

I was going to USC (School of Cinematic Arts), trying to make movies. The one thing I was good at was screenwriting, but I wasn’t good at any of the technical things. I was also freelancing for Rolling Stone, and I got to be friends with the music reviewer, the record editor of Rolling Stone. His name is Jon Landau. He became a mentor to me. He was only two or three years older. He was wicked smart, and he just knew everything about old American cinema. I learned more from Jon than I did from my teachers.

Shortly after I knew him, he quit his job at Rolling Stone because some new rock musician had read a review that Jon had written. The review became very famous. The review (in 1974) said, “I have seen the future of rock ’n’ roll, and his name is Bruce Springsteen.” And so Springsteen hired Jon to be his manager. He became the producer of all these great albums. I was hanging out with him … the summer before he switched over to Springsteen.

I remember we went to see some late screening of some old Hollywood film, and we went back to Jon’s apartment. He started playing Motown for me. I had never really appreciated Motown music, but I remember he was playing the Four Tops, the song, “(Reach Out) I’ll Be There.” (Landau told me,) “It’s a movie. It’s a three-minute movie.” He played it for me over and over again and talked to me about where the act breaks were, the things I was learning in film school about how to write a screenplay.

The way he put it was … very much in terms of the movie we had just seen, which I think was a John Ford Western. So that was a huge aha moment for me to understand the pop music that I listened to as a kid driving around in my car could be likened to a great Hollywood masterpiece of the ’40s. That’s always been that kind of territorial switching, boundary switching or code switching that I love to do in my teaching and in my lectures and in my writing. I don’t know that it started there, but that affirmed for me that works of art that come out at the same time can seem very different; they’re in different media, but they can also be saying very similar things and using some of the same motifs.

Springsteen came out with a biography a few years ago. I looked in the index for Jon Landau, and he talked about how Jon had taught him so much about movies and life. I thought, “Wow, well, I ended up teaching my course; he ended up teaching Bruce Springsteen.”

Begging Worked

It took entreaties and a cinematic trip to Norway for Teresa Radomski to finally score piano lessons.

Teresa Radomski | professor of music

Teresa Radomski has taught in the music department since 1977, helping train undergraduates for careers in opera, musical theatre, voice teaching and choral conducting. “I love what I’m doing,” she says with obvious joy. “Every single day I learn through my students, and that’s the reason I love my work and why I don’t expect I’m going to retire.”

She has an undergraduate degree from the Eastman School of Music and master’s and doctoral degrees from the University of Colorado Boulder and a fellowship in otolaryngology from the Wake Forest University Center for Voice Disorders. A versatile performer, she can be heard on three world premiere recordings: the salon opera “Le cinesi,” “Recuerdo Triste: Guitar Works of Trinidad Huerta” and “In the Almost Evening” by composer-in-residence Dan Locklair.

Back in the 1950s every little girl had to have ballet lessons, and I was no exception. At the age of 4, I had ballet lessons, and luckily for me there was this fabulous pianist who played for our dance classes in Plainfield, New Jersey. She was from Lithuania and played great music — Chopin, Beethoven. She actually played in Carnegie Hall, so she was the real deal. We did all our little exercises as little girls to this really fine accompanist. … There were a lot of times you were just hanging around. I would go right to the keyboard and stand right next to her and watch her play. I was fascinated and wanted more than anything else to play piano. It’s still in many ways my first love.

Another encounter was through a film … called “Windjammer.” I remember going as a Brownie scout or something. It was all about a bunch of sailors somewhere in Scandinavia who sailed around the world. It was basically a travelogue with three screens, and it was just really tremendous. Well, in one episode they go to Norway, and they have this huge grand piano out on the wharf, and one of the sailors happens to be a concert pianist. He sat down and played the (Edvard) Grieg “Piano Concerto in A Minor,” which today remains one of my favorites. They had all these beautiful landscapes of Norway while he was playing a haunting, beautiful melody. And I thought, “Oh my gosh! This is what I really want to do!” So, between that and the Chopin, the Beethoven and everything I heard in dance class, I begged for piano lessons.

My parents, being cautious, waited until after about a year. I practiced on my grandmother’s piano, one of those upright things in the parlor, and then one day I came home from school, and there was a big surprise in the living room. I spent hours. HOURS. My parents, God bless them, slept through me playing to the wee hours of the morning. I’m not exaggerating. I just couldn’t stay away. There was no doubt in my mind that I wanted to be a musician.

When I auditioned as a high school student to go to college, I auditioned at the Eastman School of Music, but by that time I was also becoming interested in singing through watching television. We were really lucky in my generation. We had a lot of good shows on TV that just don’t exist anymore. “The Bell Telephone Hour,” for example, or young people’s concerts of Leonard Bernstein, where classical music was there on major stations, and everybody watched.

When I auditioned at Eastman, I played piano and also sang for them, and the person who auditioned me, said, “Hmm, maybe you should think about singing instead of piano.” So, I said, “Well, fine, whatever gets me in.” Eventually I studied both piano and voice and ultimately wound up majoring in music theory, and that was one of the best decisions I ever made because I learned a lot about music composition, the mechanics of music. I could learn both instruments — piano and voice — without the expectation of being comparable to the other prospective professionals who were in school.

A Cello to Chicago

Elizabeth Clendinning persuaded her mother to ship the instrument, and soon the professor was enmeshed in world music.

Elizabeth Clendinning | assistant professor of music

Elizabeth Clendinning, a specialist in ethnomusicology, teaches popular world music survey courses and Asian music and directs the University’s Balinese gamelan, Gamelan Giri Murti, a percussion orchestra whose name translates to “magical forest.” Her undergraduate degree is from the University of Chicago and master’s and doctoral degrees are from Florida State University. Her research addresses space, time, cultural representation and pedagogy within transnational Balinese gamelan communities and within film and television music. She is the author of “American Gamelan and the Ethnomusicological Imagination.”

When I was an undergraduate student, I took a class on musics of the Mediterranean world, and one of our assignments was to go observe the rehearsal for the Middle East Music Ensemble. And so I went, pestering my teacher with questions all the way over because we were walking together. And I said, “Well, what does it feel like to play in an ensemble?” He said, “Well, why don’t you find out for yourself?”

After observing this ensemble once, I had my mother ship my cello from Florida to Chicago. I still have no idea how she did that! I began to play with this group and interact with this community … both students and Middle Eastern community (people) in Chicago. I kept having more and more questions and more and more fun, and that’s kind of how I knew that I wanted it to be my work.

The Bali (aha moment) happened a few years later — the first time that I ever saw a Balinese dance live. There was a dancer who had essentially followed her husband. He was pursuing a doctorate in education, and she happened to hear we had a Balinese gamelan ensemble on campus. She came to demonstrate the dance, and it was so beautiful and so graceful. Then we found out she was offering a class, and I knew I had to study with her. Somehow that connection between playing and hearing the music — embodying the dance and getting to know this person — made me know that I really wanted to go to Bali. From there it just grew. It became increasingly a part of my life, both the arts and the people.

I think there are aha moments for students. That’s often when someone will come up to me and say, “Professor Clendinning, I just heard whatever it was — like 12-bar blues. For the first time I can hear it now. It’s in this piece of music.” So, they discover something that had been hidden (but) there all along. … That’s amazing to see a student go from being more of a passive enjoyer of music to someone who really cannot only identify a definition from a textbook but identify something they’ve learned about in the real world.

Occasionally, I get notes from students after class ends. I remember one in particular. The student was traveling with her parents in New York City over the winter break, and (they) were traveling on the subway. There were subway musicians. She was able to stop and explain to her dad what the musician — it was a Chinese musician — was playing and what type of music it was. Seeing students be able to take something they learned in class and apply it in unexpected moments in their real life is pretty amazing