Jonathan Kirkendall ('83) in 1967 in Trafalgar Square in London during hia family's first trip back to the United States after moving to Beirut, Lebanon, four years earlier. Top photo, he worked with the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors, counseling children who have lost loved ones through the military. Photos courtesy of Kirkendall.

Jonathan Kirkendall (’83) crossed our radar as one of the many Wake Foresters whose good works we are always eager to share with alumni. We saw that this psychotherapist in Washington, D.C., has counseled children grieving over the loss of a loved one in the military.

A quick look at his bio quickened my journalistic pulse, and by the time he had talked with me about the irony-laden twists of his life, I was urging him to write a book. “Yeah,” he says, noting that a graduate school professor once told him, “You’ve lived a lot of life for a 30-year-old.”

That life began with his childhood front-row seat to civil war and revolution in two countries as the youngest son of Southern Baptist missionaries, yet many of his memories are idyllic.

First-year students at Wake Forest sometimes undergo dizzy highs and lows as they walk onto the university stage, but Kirkendall arrived as a foreigner in his own country. An excellent student who won early admission, he struggled initially. “I just bombed,” he says. “(Now) I understand … I was pretty depressed.” Yet he came back strong in his sophomore year, enchanted by all that the liberal arts offered him.

At each stage, fear and trauma have both plagued him and opened doors to finding his mission and his place in the world. (And maybe a best-seller one day.)

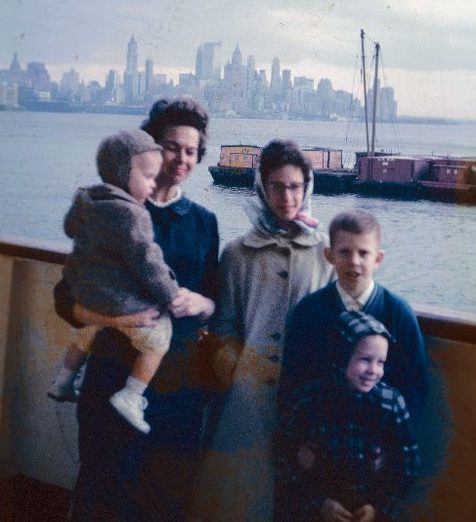

Jonathan Kirkendall, held by his mother at age 2, as the family prepares to sail tfrom New York City o Lebanon in 1963.

***

Jonathan Kirkendall left St. Louis at age 2 with his missionary parents, two brothers and a sister, bound for Beirut, Lebanon, where his father was pastor of a Baptist church for expats.

Beirut was “a Garden of Eden … amazing and beautiful.” The family spent summers and school holidays in Saudi Arabia, where he and his siblings frolicked in swimming pools while his father ministered to employees of Lockheed, Raytheon and other U.S. companies there.

But Kirkendall’s paradise gradually descended into a 15-year civil war that began in 1975. He learned that if he woke up and heard gunfire, classes were canceled that day. Often, he had to walk the long way home to avoid rooftop snipers. His father was attacked while opening the church one day. When he was in fifth grade, his dad was kidnapped and released three days later only because his Palestinian Muslim barber learned his location, and a Lebanese doctor pleaded for his life.

Finally, the family left — for Tehran, Iran.

“I tell my friends, ‘frying pan-slash-fire,’” Kirkendall jokes.

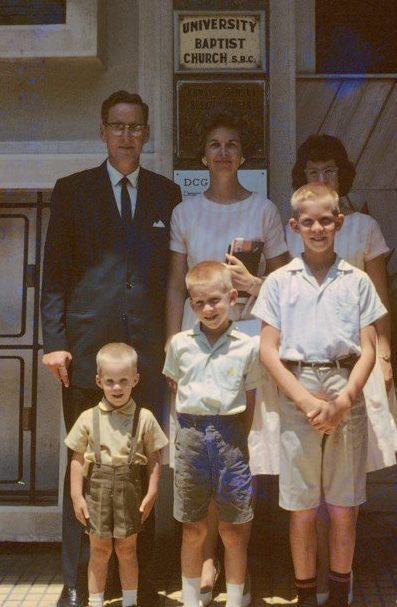

The Kirkendall family, when Jonathan was a preschooler, stand in front of University Baptist Church in Beirut, Lebanon, where Jonathan's father was pastor.

***

Kirkendall’s father traveled to support missionaries in Iran, India and Bangladesh. But the Islamic Revolution was creeping north to Tehran. Unlike in Lebanon, Americans were hated. Kirkendall was excelling and happy in high school, assuming that the Shah of Iran, a U.S. ally, would never be overthrown. But danger hung over everything. The large American school was a security risk. “We had to walk past sandbags and soldiers with bayonets. It really did impact our life.”

He woke up one morning to what sounded like running water. “My dad came in and … said, ‘There’s a big demonstration going on, and (our youth minister) Michael’s kind of caught in the middle of it. You want to come with me and go get him?’”

The “running water” turned out to be the murmur of hundreds of thousands of protesters chanting and marching a half mile away on the street where Michael lived.

“So that was fun,” he says with the wry sense of humor that infuses his perspective on all of life’s ups and downs. “My dad stayed in the car, and I ran up and got (Michael), and then we jumped in the car and drove back home.”

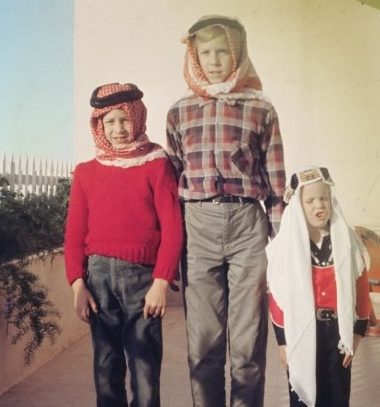

Kirkendall with his older brothers, wearing the Arab keffiyeh.

Conditions worsened. “Being in Iran was like, ‘Here we go again.’ I had watched Lebanon devolve into civil war, and so there was a part of it that was normal for me. But I will say it was very stressful.”

At dusk, cries of “Allahu Akbar” (God is most great) spread across the ubiquitous rooftop patios, a signal to take to the streets to protest. “We could see the fires, hear the gunfire. We could hear people screaming. The skies were orange. It was intense.”

By November 1978, Kirkendall, the only sibling at home, slept on the floor in his parents’ room. They taped the curtains taut to the wall so firebombs would bounce back out.

Classmates, including his best friend, disappeared without warning as families left the country. While the Kirkendalls spent Christmas in India, his school closed, and his family didn’t return. An active senior, up for scholarships, he was crushed. “I just remember that last day (of school) being like a nightmare. Everything is slipping away.”

Young Jonathan with his father and older brothers sightsee in an unknown Mideast location.

***

Kirkendall had learned about Wake Forest from alumni doctors at a Baptist hospital in India. Wake Forest offered discounted tuition for missionaries’ children. It had a medical school he hoped to attend and a name he loved — “It sounded kind of medieval to me.”

He won early admission, but his academic prowess failed him. “I couldn’t focus on anything. I had no idea I needed counseling.”

He was in culture shock, too. He asked his roommate what a mixer was and what to wear. The answer was docksiders, khakis and a button-down. “I had no idea what those were.” A friend at Salem College called her boyfriend, a Wake Forest law student. “He was such a nice guy. He came over and showed me how to dress.”

He learned that his family dog died. His parents moved to an assignment in Belgium. “I had nowhere ever to go on weekends. It was miserable. I would go in the stacks of the library, and I’d have these panic attacks, feel like my heart was racing.”

A medical student and his wife “adopted” him. He leaned on a few fellow missionary kids and found a home at the Baptist Student Union. Walking to Reynolda Gardens calmed him. “Weirdly, the pine trees in North Carolina smelled like the pine trees in Beirut. For this homesick kid, it really nourished me.”

He spent the summer in Brussels and returned invigorated. Having given up on pre-med, “I took anything and everything that interested me.” Tears come to his eyes when he talks about the “saving grace” of his semester at Casa Artom in Venice, where “just being … overseas was like home.” The late Bianca Artom who taught Italian there, took him under her wing.

Wake Forest's Demon Deacon and other mascots appeared at Fort Myer in Arlington, Virginia, at a 2016 event by the NCAA for the nonprofit Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors, where Kirkendall worked. TAPS supports military bereavement and children who have lost loved ones in the military.

He graduated as a philosophy major with mastery of French, Italian and German, but “I was lost. I had no idea.” He delivered newspapers, worked at a furniture factory and squirreled away his tips as a hotel bell hop to pay for a year in Europe. He was back in Winston-Salem waiting tables when his roommate’s fiancée died in a car accident. “I was like, ‘Good God, Lucy was alive yesterday, and she’s not alive today. I’ve got to figure out what I’m going to do. I need to move on here.’”

He wasn’t ready yet for graduate school. A friend told him about the Dorothy Day Catholic Worker House, an anarchist collective in Washington founded in the 1920s. He lived there, much to his parents’ consternation, for two years. And what happens in an anarchist collective? “Not a lot of decision-making,” he says, laughing. The group housed homeless people and focused on building community, with the radical notion of sharing decision-making with them.

***

At age 26, after living safely through two wars, Kirkendall experienced the biggest trauma of his life. As he walked up 16th Street in 1986 with a friend, four muggers attacked them and knifed Kirkendall in the face. Cuts and fractures in his skull and face required a year of recover, “but my community really took care of me. … The muggers got $10. I got a facelift.”

He can joke about it now, but the attack gave him nightmares and insomnia. His friends opened the door to his career by urging him to see a therapist.

“And I kind of loved it. I was like, ‘Eureka! I want to do this work!’” he says. “When I was a kid, I’d always play teacher or doctor. I would perform surgery on my stuffed animals, or I’d line them up and teach them. Being a therapist nailed it right between those two. … I spend a lot of time with people who are suffering, helping them create lives that can diminish that suffering.”

Kirkendall took up pottery and almost pursued an MFA in ceramics but decided instead to attend Naropa Institute to study mental health counseling and meditation. He still has a pottery studio and sells his creations.

He had become agnostic but retained a deep interest in spirituality. He decided to pursue a graduate degree at Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, intrigued by its focus on the relationship between meditation and mental health counseling. Meditating every day “started changing my life in positive ways, … the ability to concentrate. … All of the uproar of my emotional life died down. … As it turns out, doing nothing is a very powerful practice. And much harder than it sounds.”

He became a Buddhist, to his Baptist parents’ dismay.

Oh, and he’s gay. More parental dismay. His father has since passed away, but both parents accepted him in every way and welcomed his husband, Scott Perkins. The couple met in Boulder, lived for two years in New York City while Kirkendall worked for the American Red Cross, then moved to Washington.

***

Kirkendall found “the best job ever” as a social worker for Miriam’s Kitchen, a breakfast program for homeless mentally ill people. Two years later, “we ended up winning The Washington Post award for excellence in nonprofit management, and we grew Miriam’s Kitchen into having full-time case managers, an art therapy program, a writing program, doctors coming in.” First Lady Michelle Obama volunteered there while she was in the White House.

Kirkendall left as social services director to start a private practice. In 2006, a new calling emerged. His nephew deployed in Iraq. One brother was a U.S. Air Force officer, and the other a Navy chaplain. “I was very much against the war, but I also felt like I needed to support the troops because the troops were my family.”

He volunteered for the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS), a nonprofit that works with military bereavement care and offers camps for grieving military children. “I volunteered so hard that in 2015 they offered me the position of clinical director for youth programs. …

I’m really proud of that work. We served thousands of kids.”

He remembers one of his happiest moments, training a roomful of 200 military personnel on the needs of the bereaved military child.

“And I just thought, ‘Wow, who knew that this guy who grew up as a missionary kid who identifies as a gay, leftwing Buddhist (would be) working with the military at Fort Hood, Texas,” Kirkendall says.

He has since returned full-time to his clinical practice.

“As a kid I was forced to do it, due to circumstances, but now as an adult I choose to do it, which is to walk into those really hard places with a mind of curiosity and kindness and just be there, be present there, and somehow in that presence, the pain can be transmuted.”