(This story originally appeared in 2020.)

If you think that the replicas of the human skull that Mark “Pops” Craven (’72) creates are a bit odd or gross or even creepy, he’d like to change your mind.

The skull is “the fortress of the mind,” said Craven, with half a dozen skulls, some colorfully decorated and others that look like they just came off a skeleton, keeping a close watch on him. “It protects our brain and our creativity. It’s nothing to be afraid of.”

His eye-catching skulls certainly grab your attention, but that’s not the end of the story as he pursues his third act as a sculptor and painter as he’s pushing 70. (He’s moved into something less creepy these days, pet portraits.)

He spent much of his work life as a button-down businessman — owner of an upscale men’s clothing store and a retail liquidator — before trading his expensive suits for flannel shirts, going back to school to earn a fine arts degree, growing his hair long enough for a ponytail and reinventing himself as Pops the artist.

Mark "Pops" Craven ('72) and a few friends at Penny Path Café & Crêpe Shop in Winston-Salem.

“It’s never too late to achieve your dreams,” he said. “For 45 years I chased money, and money can’t buy happiness. It can buy you things. But happiness comes from doing what you love, and I finally found what I love, creating.”

Some of his skulls are displayed at Penny Path Café & Crêpe Shop in Reynolda Village in Winston-Salem, where he works part time.

He’s been through a lot to get where he is today — declaring business bankruptcy, not once, but twice; losing his home, not once but twice, to foreclosure and a fire; and losing his wife to multiple sclerosis and a son to a drug overdose. “It was the story of Job,” he said. But now, finally doing what he’s wanted to do all his life, he wouldn’t change a thing in his journey.

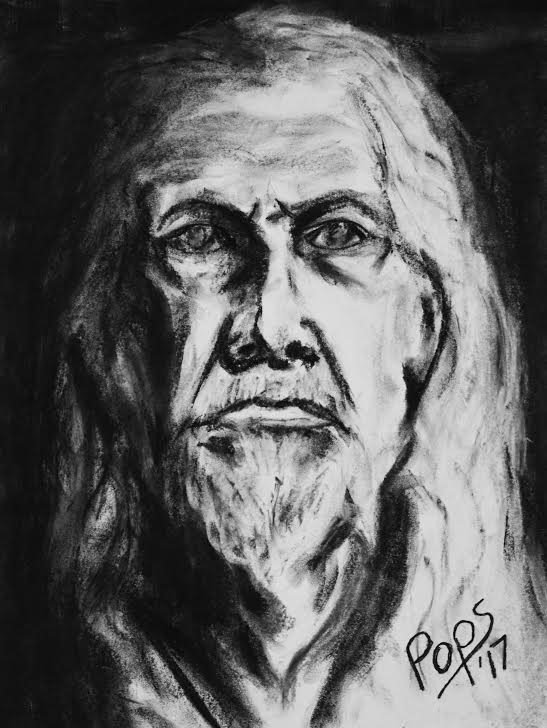

A self-portrait by Mark "Pops" Craven.

Craven has always had an artistic side. Growing up in High Point, North Carolina, he wanted to be an architect. He designed his first project, a cantilevered treehouse, when he was 11. As a teenager, he designed the floor plan and fixtures for his dad’s new clothing store, Arnold Craven Clothier & Furnisher, in High Point.

He followed his sister, Pamela Craven (’60, P ’85), to Wake Forest. He took business courses, joined Lambda Chi and “improved his social skills.” Translation: “I partied a lot.” But he also found time to take a painting class from artist-in-residence Ray Prohaska and still has his portfolio from the class.

But he shelved his artistic dreams to join his parents and sister in the growing family business. He opened new stores in Greensboro and in downtown Winston-Salem, in what was then the new Hyatt Hotel, and produced a slick national catalogue. He cemented his standing in the business community by serving a term on the High Point City Council.

The good times didn’t last. Changing clothing trends and competition from larger retail chains forced Arnold Cravens into bankruptcy in the mid-1990s. As difficult as it was to close the family stores after three decades in business, Craven found a new career: helping other struggling retailers, from furniture stores to clothing boutiques, shut down.

“I became the Dr. Kevorkian of retail,” he said, referring to Jack Kevorkian, a prominent advocate for assisted suicide for terminally ill patients in the 1990s. “When I was in college, you would come out and have your lifetime career. Now you have to reinvent yourself all the time.”

That second career ended as his first career had — in business bankruptcy — when he became a fulltime caregiver to his wife of 42 years, Jonnie, during her 10-year battle with MS. She once asked him what he wanted to do with the rest of his life after she was gone. “Be an artist,” he said. “OK,” she told him, “go back to school.” He took her advice and enrolled in the undergraduate art program at UNC Greensboro when he was 64.

Six months after Jonnie died, his oldest son, Spencer, died from a drug overdose at age 39. Throughout his wife’s illness and death and his son’s death, he relied on his strong faith and pursuing his interest in art to keep him going as he became Pops. His much younger classmates at UNCG gave him the nickname once they realized he was a student and not the professor.

Craven sculpted "The Last Dance" as a tribute to his wife, Jonnie. "Just a few months before Jonnie died from the ravages of MS, she asked me for one last dance. I gently helped her up from her bed and placed her feet on mine and we moved to an imaginary song as we had done so many times before."

Craven sculpted his first replica in clay of a real skull for a class project at UNCG. His professor thought it was so realistic that she encouraged him to make duplicates. Sculptured Skulls By Pops was born. He uses a mold to cast the replicas in resin, a composite, bone-colored blend that can be easily molded.

He sells the skulls undecorated ($49) or decorated ($69 – $89) in bright colors, tie-dye, camouflage (a hit at gun shows) and in other designs. He’s found enthusiastic customers in bikers and tattoo artists and at music festivals and has sold about 200.

The skulls may grab your attention, but Craven hopes you’ll look deeper to find inspiration. He doesn’t shy away from discussing his business failures and personal losses. He’s emerged from his “valley of the shadow of death” — as he puts it — upbeat and optimistic.

Now remarried and happily painting and sculpting, Craven said his life has never been better. “I never lost my faith. I believe that things happen for a reason. Despite everything that I’ve gone through, I’ve never been as happy as I am today.”

Mark "Pops" Craven at his graduation from UNCG in 2018 with his new wife, Terri. He was 68 when he graduated Magna Cum Laude with a bachelor of fine arts degree.<br />