Lead singer Chris Mowry ('82), shakes the maracas in April 1982 for The Shakes, with Henry Heidtmann ('85) and Steve Dixon ('82) in a show behind Reynolda Hall. Bandmates Stan Guthrie ('82) and Scott Snedecor ('82) not pictured. Photo by the Old Gold and Black. Top photo is a coyote in Piedmont Park in Atlanta. Photo by Larry Wilson, Mowry's co-founder of the Atlanta Coyote Project

Chris Mowry (’82) rocked it as lead singer of The Shakes, a popular “new wave” band born on campus.

But his biology major ultimately led him to music of another kind — the yipping and howling of coyotes, known as “song dogs” for their vocal dexterity. Mowry is a biology professor at Berry College in Rome, Georgia, and co-founder of the Atlanta Coyote Project.

Mowry has master’s and doctoral degrees from Emory University, where he met his project co-founder, ecologist Larry Wilson. Mowry was one of 13 lead investigators on the 20-year Canid Ecology Project in Yellowstone National Park from 1990 to 2010. He and his wife, Lisa Kline Mowry (’82), live in Marietta, Georgia.

Wake Forest Magazine talked to Mowry about what makes coyotes so compelling (a bit about his days in The Shakes). His comments have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. What fascinates you about coyotes?

They’re resilient because of a broad diet, do very well around humans. The federal government kills around 70,000 coyotes a year. It’s a very controversial animal. It’s very misunderstood. It elicits very strong emotions in people, both positive and negative.

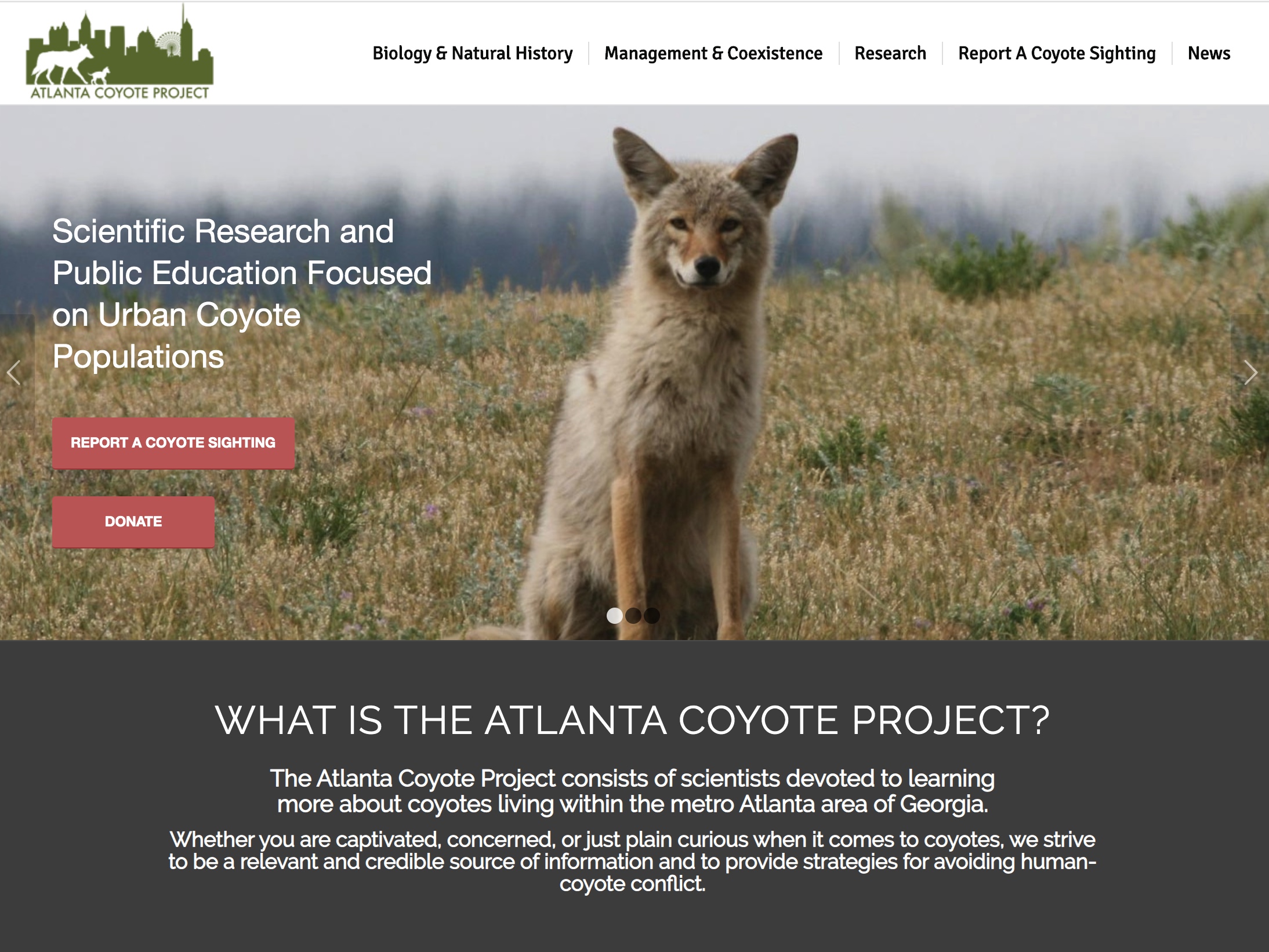

Chris Mowry's home page of the project he co-founded with Larry Wilson, an ecologist and adjunct professor at Emory University who retired from Fernbank Science Center in Atlanta. He and Mowry met in graduate school at Emory.

It’s a very interesting animal to study biologically. Coyotes are a lot like us. They live in family groups. Male and female will pair up and bond for life. Both are involved in the rearing of offspring, as are older brothers and sisters. They’re not living in these big unrelated groups. They’re living in small nuclear families. They’re very protective of their offspring. They’ll move their den if it becomes detected. They’ll move their pups if they feel they’re threatened.

They’re playful. They’re very communicative. Coyotes have the ability to modulate their voices so it sounds like there are more of them than there really are. The howling, the yipping, the barking, one, is to stay in touch with each other, and secondly, it’s to tell rivals, “This is my territory, stay away.” It’s … an auditory fence. Very cool.

The gray wolf, the red wolf, the coyote and our dogs that we all love, they’re all the same genus (but different species). They could potentially interbreed, but that’s not a normal, common thing, mainly because they don’t come into contact with one another.

The incidence of attacks of coyotes on humans is extremely low. You’re much more likely to be struck by lightning … or to be attacked by your neighbor’s dog. — Chris Mowry

A coyote in Piedmont Park in Atlanta. Photo by Larry Wilson.

Q. What are the biggest myths about coyotes?

There are lots of them. We go through all of this on our website, AtlantaCoyoteProject.org. We just published a paper that showed high biodiversity where coyotes are living and reproducing. The myth is they’re eating everything in sight. That’s not the way apex predators behave. They keep smaller species in check, and they eat a little bit of this and a little bit of that.

Another is they’re going to eat my child. The incidence of attacks of coyotes on humans is extremely low. You’re much more likely to be struck by lightning … or to be attacked by your neighbor’s dog. Yes, they are wild animals, and we caution people to treat them as such, but they want usually very little to do with us and keep out of sight.

Q. What about pets?

Pets are not natural prey items for coyotes. The coyote’s got this wide menu of things to eat, and even in urban environments, there are plenty of squirrels and rats and chipmunks and fruiting trees and insects that are much easier for a coyote to eat than a cat or a small dog. It does happen, but it’s usually associated with … people are feeding pets outside. They’re losing their fear of humans. That’s when problems start.

The other thing that can happen is they can get sick. People put out rat poison. You kill the rat or mole, and the coyote finds it and consumes it. It may not kill the coyote, but it suppresses the immune system. So they get mange. They lose fur. Scratching develops sores. It’s a slow gradual death. They become desperate so they begin doing the behaviors that the coyote wouldn’t normally do, like go after pets.

Carmine, an overfriendly, rare black coyote in Marietta, Georgia. Mowry helped capture Carmine to get him to a wildlife sanctuary. Photo by Glenda Elliott.

Q. Do they get rabies?

Rabies is extremely rare in coyotes. In the Southeast, the main vectors for rabies are raccoons and skunks and bats. Seeing coyotes in the day is not a cause for alarm — “Oh, they’ve got rabies.” Coyotes in their natural habitat are active during the day. They simply switch to being nocturnal when they’re around humans.

Q. How did you end up studying coyotes?

I was trained as an animal ecologist, and I studied for many years African primates and spent a lot of time in various countries of Africa. But it was hard to get students involved in research that way, so it was really a student who got me involved in coyotes early on. Berry College sits on 26,000 acres. When I first got to Berry in 1994, I heard this sound, and I really didn’t know what it was. It was coyotes. They were gradually moving eastward, coming from west of the Mississippi River because there were no red wolves around anymore to keep them out.

Mowry, right, and Brandon Sanders of Sanders Wildlife, who does humane nuisance wildlife control, after finally trapping Carmine, who looks lighter than its black coat because of the camera flash. Photo by Lara Shaw.

Q. What happened to the red wolves?

Coyotes and the gray wolf, which is a larger animal, they co-evolved together out West. The red wolf is a little bit smaller than the gray wolf, and it was the endemic species in the Southeast — hence, the red N.C. State (University) Wolfpack.

We wiped out the red wolves in the Southeast over a hundred-year time span. It was a concerted effort by the U.S. government: trapping, killing, poisoning, you name it. … to protect livestock, fear. They’re competitors; they go after some of the same foods that we do. We as human beings have a love-hate relationship with predators, particularly wolves.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, coyotes had moved in and were throughout the state of Georgia, and in North Carolina. Coyotes (are) now in every state except Hawaii. The only place with red wolves (in nature) is at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

.on the coast of North Carolina (established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1984 near Manteo to promote the endangered species.)

Carmine, in the enclosure above, next to Wilee, a friendly female coyote. Both are at the Yellow River Wildlife Sanctuary in Georgia. Mowry is optimistic the two overly friendly coyotes, both neutered, can keep each other company and live safely without getting into too-close encounters with dogs or humans. Photo by Larry Wilson.

Q. Please share the story of Carmine, the black coyote you helped capture in a Marietta, Georgia, neighborhood, as described by Atlanta magazine.

We published a paper a few years ago about melanistic coyotes, with a black coat. It’s a genetic trait, really striking. Right after Christmas, I got a call from a woman because we had previously used her yard as a study site. She had persimmon trees, and coyotes love persimmons. She said, “There is this black coyote running around my neighborhood and playing with other dogs.” The video is incredible. (The caller, Kris Hoffman, named it Carmine for the “Laverne & Shirley” TV show character with jet black hair.)

We never would have intervened. We’re scientists. That’s not what we do, mainly because it’s not possible to relocate coyotes. They’re very territorial. They have mates. State law says that you can’t trap a coyote; you can’t relocate; you have to euthanize. (Worried about the coyote’s habituation to humans and pets), we got special permission from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources because we had a potential home for it at Yellow River Wildlife Sanctuary. They had previously asked us if we would get some educational materials together for the coyote they already had. I called them and jokingly said, “You want another coyote?” and they said, actually, we do. So the stars aligned in this instance.

Through our website and our Facebook page, we started notifying people … to please let us know if you see it. Responses started pouring it.

We were following this thing all around town. They’re very smart. We set up a live feed and watched it almost go into traps several times. With a concerted effort, we were able to capture Carmine (on Feb. 17). We have high hopes that he and this resident coyote (both neutered at the sanctuary) will get along.

From left, Steve Dixon ('82), Chris Mowry ('82) and Henry Heidtmann ('85), with Scott Snedecor ('82) on drums, play in 2007 at The Garage in Winston-Salem for a reunion of The Shakes during Homecoming. Band member Stan Guthre ('82) died in 1986. Photo courtesy of Mowry.

Feeling The Shakes

Chris Mowry’s name rings familiar for a certain cohort of Deacons because of his days as lead singer of The Shakes. He, Steve Dixon (’82) and Stan Guthrie (’82), all in Taylor dorm, connected as freshmen with Scott Snedecor (’82), who lived in Poteat House. They formed various bands, eventually creating The Shakes by the time they were seniors.

“But we were missing a bass player,” Mowry says. “We brought in Henry Heidtmann (’85), who was a freshman.”

The band performed in Reynolda Hall, outside Reynolda Hall and all over town, playing new wave rock, “Elvis Costello and The Clash and bands like that,” Mowry says. “We used to get hundreds and hundreds of people who would go to our shows. It was neat.”

They recorded in Winston-Salem with Mitch Easter, the famous producer for the band REM, and got to know REM members.

“I was really on a pre-med track at Wake Forest,” Mowry says. “My biology professors at Wake were great — Peter Weigl, Charles Allen (’39, MA ’41), Gerald Esch (P ’84). Clearly my major prepared me for what I do now, and I treasure that and greatly appreciate that.

“But I realized I had other interests. Right after college, I moved to Atlanta for a variety of reasons. One of them was to pursue music with my former bandmates. I was just not committed at that point to a career as a physician. I pursued music pretty seriously and finally settled down and went to graduate school at Emory.”

Guthrie died in 1986, but the other bandmates stay in touch and have played at Homecoming reunions. Mowry’s continuing passion for music has also inspired his son, Alex, 23, who works in digital marketing and graphic design. They’ve recently started their own band together. The coronavirus has delayed their debut, but they’re busy writing and recording their own songs. — Carol L. Hanner

Listen to The Shakes’ song “Take My Picture.”