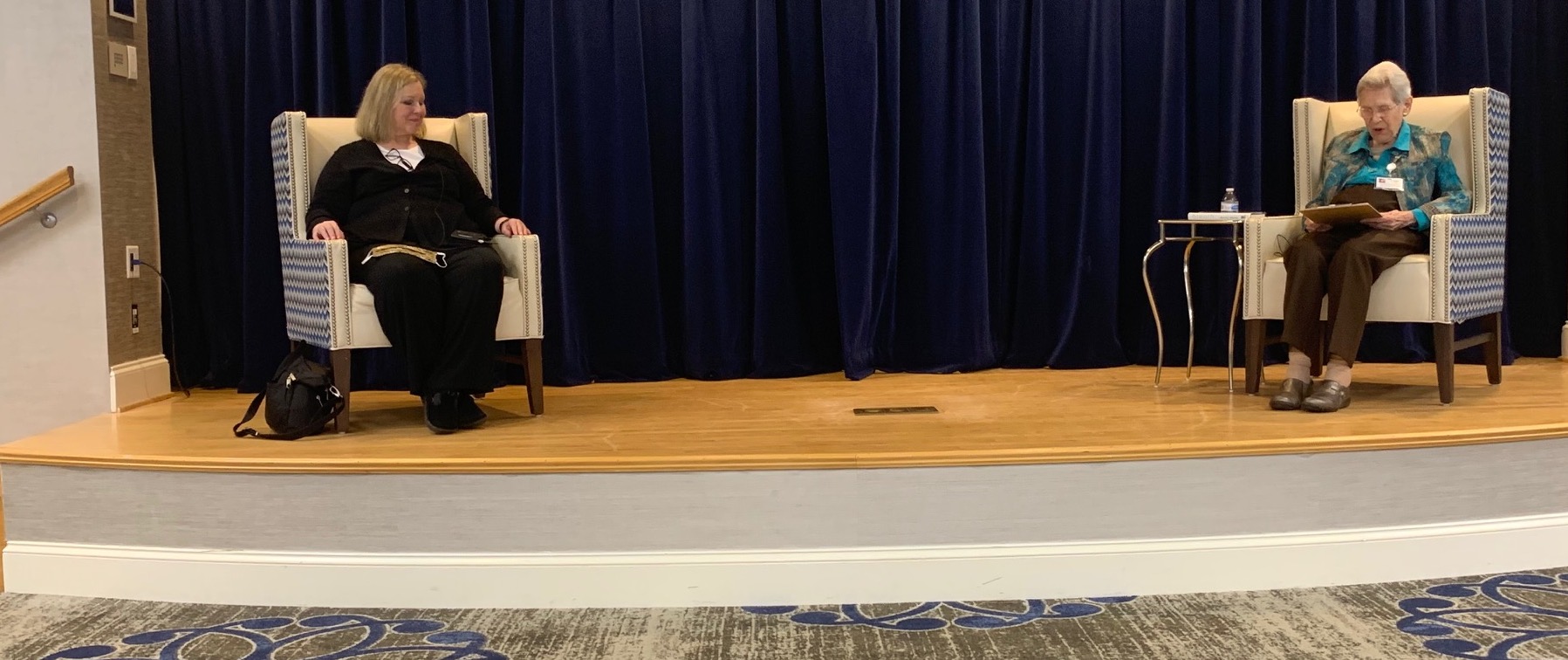

A polio ward is packed with patients, many children, kept alive by iron lung machines. Top, Mary M. Dalton ('83), a Wake Forest professor and filmmaker, sits with Martha Ann Mason ('60).

Martha Ann Mason (’60) wanted to go home. It was 1949, and the fearless 12-year-old had lain paralyzed for a year inside an iron lung, an 800-pound machine that was keeping her alive by inflating and deflating her polio-ravaged lungs. Only her head was visible, with an airtight rubber seal encircling her neck.

Polio had killed her 13-year-old brother, Gaston, her hero and adventure partner. The day after his burial in 1948, Martha was hospitalized.

Now the doctor in this Asheville hospital said she could go home to her village of Lattimore in southwestern North Carolina, but he warned her parents she was unlikely to live more than a year in the iron lung at home.

In Martha’s telling, the doctor asked her, “Do you think you can live with being inactive, with being a vegetable, being in an iron lung for the rest of your life … not moving from the neck down?”

Martha looked him straight in the eyes and answered:

“No, but I think I can live above that.”

Martha Mason. Photo by Robert Lahser

Inspiration Beyond

Words — read, written, spoken, heard — opened doors beyond Martha’s iron behemoth. Learning and connecting with other people allowed her to live a mental and literary life above her physical confinement. She died in 2009 at age 71 after six decades in the iron lung, longer than any person known to survive living full-time in the machine.

She could not move, but “the Belle of Lattimore” reached her dream of becoming an author. She won honors bestowed by two universities and indulged a constant stream of visitors. From high and low places, they brought food and conversation to her humble home, where neither the swoosh of the machine’s bellows nor her neighbors’ desire for her company ever stopped.

This week, 11 years after Martha’s death, a series of synchronicities has connected Lorna Lane, a 93-year-old Deacon mother, with Wake Forest filmmaker Mary M. Dalton (’83) to share memories of Martha. They brought her story of courage and hope to Lane’s coronavirus-weary neighbors at River Landing at Sandy Ridge, a retirement community in High Point, North Carolina.

“The pandemic has been a stressful place to be living,” said Lane, a nurse who cared briefly for Mason in 1950 at a polio hospital in Greensboro, North Carolina. “A lot of us have had despair and uncertainty, and I began to search for some ideas about who would be an inspiration for us.”

Mary Dalton (left) and Lorna Lane talk about Martha Mason on a stage, with social distancing, at River Landing at Sandy Ridge retirement home. They were broadcast to residents' rooms.

Lane reached out this summer to Dalton, a professor of communication, film studies and women’s and gender studies, after discovering Dalton’s 2005 documentary, “Martha in Lattimore.” This week, Lane and Dalton spoke to River Landing residents watching from their rooms on an in-house channel, followed by a showing of the documentary.

“I’m always happy to try to introduce Martha to other people,” Dalton said. “I hope when you see the film that you’ll get a sense of that spirit that she brings because she really was probably the most remarkable person I’ve ever met.”

Viral Damage

Polio is an incurable, contagious viral disease that attacks the nervous system. It can incapacitate breathing muscles and be fatal. U.S. outbreaks peaked in 1952, infecting more than 57,000 people and killing 3,145, many of them children. A vaccine was approved in 1955. The disease exists now only in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

When Martha was hospitalized in 1948, even parents’ access to polio wards was restricted to occasional visits. Dalton says Martha’s mother was determined to be there. “She had lost one child. She wasn’t going to be apart from her other child,” Dalton said. Euphra Mason took hospital jobs sweeping floors or working in the cafeteria so she could learn every detail of Martha’s care. Martha never got a bed sore.

Dalton didn’t meet Martha in person until 2000, even though Dalton’s mother and many of her kin grew up down the road from the Masons in Cleveland County. Dalton remembers at age 6 or 7 sitting in her grandparents’ farmhouse looking at her uncle’s high school yearbook. “I saw this picture of this head sticking out of this big metal tube. It really kind of scared me.” She ran to her mother and grandmother in the kitchen. “I said, ‘What is this? What is this?’ My mother … said, ‘Well, that’s Martha Mason,’ just very matter of fact.”

Martha Mason, right, and her older brother, Gaston, lived what she called an idyllic life in Lattimore, a village of 400 people in southwestern North Carolina. He died of polio in 1948 a week before she was hospitalized with the disease.

Neighbors in the small town, including Dalton’s grandfather, watched over the Mason family. “Martha’s family needed a roof, so you put a roof on the house. That’s how things were,” Dalton said.

Lane also made an early connection to Martha that didn’t flourish until decades later. Fresh from nursing school in Raleigh in September 1950, Lane followed her fiancé to Greensboro and took a job in a hospital built in less than three months to accommodate 134 polio patients, including a few women who gave birth inside iron lungs. Martha, who often returned to hospitals for treatments or infections, was one of Lane’s patients.

Lane married in January 1951 and moved to Winston-Salem for her husband’s job at Western Electric. Having four children in eight years, she left nursing for a decade and lost touch with Martha.

Lorna Lane stands in her white nursing uniform with a bouquet of red roses for her graduation from Rex Hospital School of Nursing in Raleigh in September 1950. She was named "Ideal Nurse" by her classmates and received an engraved gold watch.

At home, Martha’s parents and two caretakers stayed with her 24 hours a day. Determined to use her mind if her body couldn’t serve her, Martha read insatiably. Her mother or a helper turned each page of the book in a wire frame above her head. She dictated her homework to her mother.

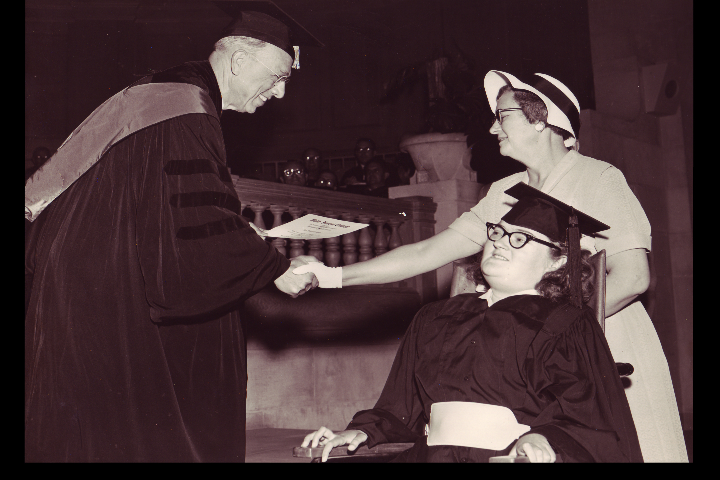

With homeschooling, she graduated first in her high school class, then moved with her parents to a faculty apartment at Gardner-Webb University, topping her class again and earning an associate’s degree. She repeated the feat, including first in her class, from a faculty apartment at Wake Forest. Her father, Willard, took a job in Winston-Salem, and her mother took notes and typed her papers.

The University set up an intercom system so Martha could participate in classes. “She was probably one of the first distance learning students,” Dalton said.

Martha Mason in a wheelchair to receive her diploma at Wake Forest in 1960 in the first class to graduate on the Winston-Salem campus. She is with her mother, Euphra Mason.

Community Hub

At home, Martha drew family, friends and neighbors into her charming sphere.

As she grew up, people brought food and stayed for conversation and advice. Boyfriends were vetted. Local political candidates sought her approval. Gov. Jim Hunt and his wife, Carolyn, came by now and then. So did crime novelist Patricia Cornwell, whose first husband, Charlie Cornwell, grew up nearby. Martha essentially ran a social salon.

“She really wanted to engage with people as friends, but not as an oddity or curiosity,” Dalton said. “She thought pity was the worst word in the English language.”

“I’ll make them forget that they’re in the presence of all this machinery,” Martha says in the documentary.

Her innate curiosity fueled her. “I don’t consider myself an intellectual. But I consider myself a searcher, a seeker,” she tells Dalton.

She relished each technological advancement. In the early 1990s, a mechanical page-turner allowed her to read to her heart’s delight. Her first computer in 1993 opened the universe. Voice recognition allowed her to write privately and search the web by herself.

“I don’t consider myself an intellectual. But I consider myself a searcher, a seeker.”

She never lost her optimism and concern for others. Soon after she came home from Wake Forest, her father suffered a massive heart attack at age 50. Her mother cared for them both.

Martha with her father, Willard Mason.

When a stroke eventually reduced Martha’s mother to child-like functioning, Martha insisted on bringing her back from the nursing home to oversee her care.

“Sometimes I was her mother. Sometimes I was her infant Martha. Sometimes I was the Martha of today,” Martha says in the documentary. “Look at all she did for me. The very least I could do when she had a need was to see to it.”

Euphra Mason, Martha's mother, lived at home with Martha after having a stroke that left her with child-like functioning.

Synchronicity

As a young faculty member at Wake Forest, Dalton began thinking about Martha again. “By the time I had been teaching there for a while, I just got this very powerful feeling that I needed to meet Martha Mason. …It was a calling that out of nowhere it just got lodged in my brain.”

She mailed a note, mentioning church and family connections and her friendship with Provost Emeritus Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93), who happened to be Martha’s favorite professor. Dalton visited on Christmas Eve 2000. “We became fast friends instantaneously.”

Lane knew that Martha graduated from Wake Forest, as did three brothers of Lane’s husband and eventually Evelyn Lane Frost (PA ’75), one of their three daughters and a missionary in Africa for more than 30 years. Lane’s son, Roger David Lane, attended Bowman Gray School of Medicine for a year before switching to pharmaceuticals. He and his wife were killed in the 1996 ValuJet Airlines crash in the Florida Everglades. Lorna’s husband passed away two years ago.

At one point, Lane contacted Martha, and she and her husband stopped by on their way to see his family. Then in 2003, the Lanes attended a ceremony at Gardner-Webb honoring Rowell Lane (’37, MA ’48). To Lane’s surprise, Martha was being honored with an honorary doctorate.

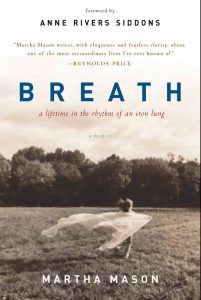

Martha also accomplished a lifetime goal in 2003; she published her memoir, “Breath: Life in the Rhythm of an Iron Lung” (John F. Blair Publishing). Lane read it and loved it.

The same year, Wake Forest awarded Martha its Pro Humanitate Award for living a life “for humanity.”

Lorna Lane introduces Mary Dalton on stage at River Landing retirement community in High Point, North Carolina, in a presentation broadcast to the 600 residents’ rooms.

Martha pursued unsuccessful treatments to try to regain use of her hands, but she eschewed respirators as invasive and infection prone.

In 2009, she told Dalton not to move ahead with a birthday gift of a Netflix subscription. “She knew she was dying,” Dalton said. “She had decided that she was not going back to the hospital because she didn’t like having to be taken and losing control over her care. I gave her the subscription anyway.”

On May 4, 2009, Martha died, a few weeks short of her 72nd birthday. Today, her life continues to inspire. The response to the presentation by Dalton and Lane was encouraging, Lane said.

“One lady really thanked me for telling her to watch it,” Lane said in an email. “She said, ‘… and we complain about the least thing,’ (and she has had part of her jaw removed with cancer.) She really got the message.”

To live above it.