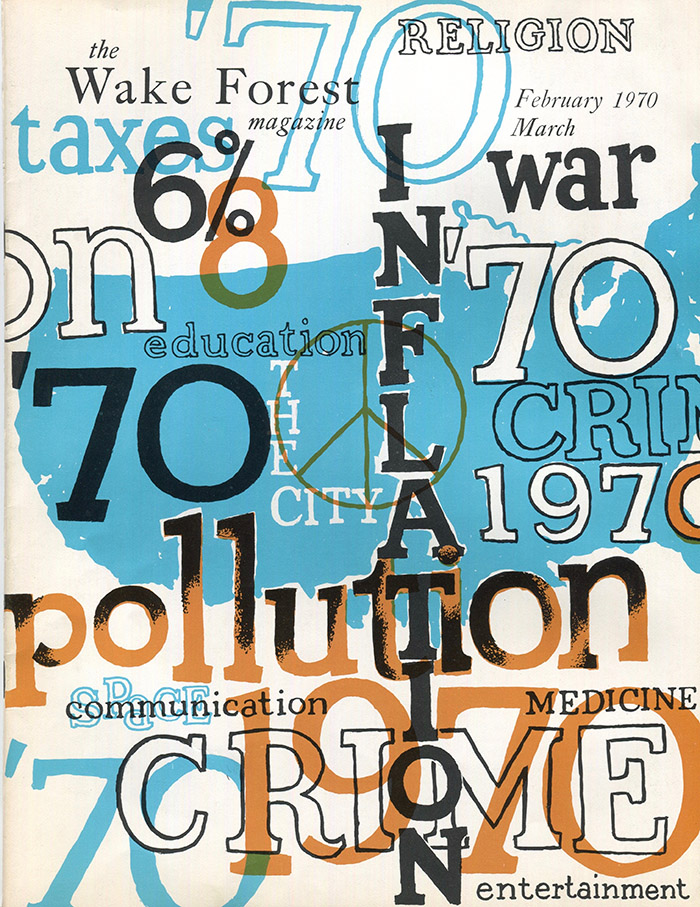

Montage for the cover of the February/March 1970 Wake Forest Magazine by illustrator and painter Ray Prohaska, at the time artist-in-residence. The cover story featured alumni predictions for the 1970s.

Against a backdrop of a pandemic, political turmoil and protests in the streets, 2020 had echoes of the collective uprising that marked U.S. history in the 1960s and early 1970s.

In “The History of Wake Forest University, Volume V,” Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) wrote that 1969-1970 was “the most turbulent period in modern Wake Forest history. … The campus troubles in the spring of 1970, were, for a college like Wake Forest, without precedent.”

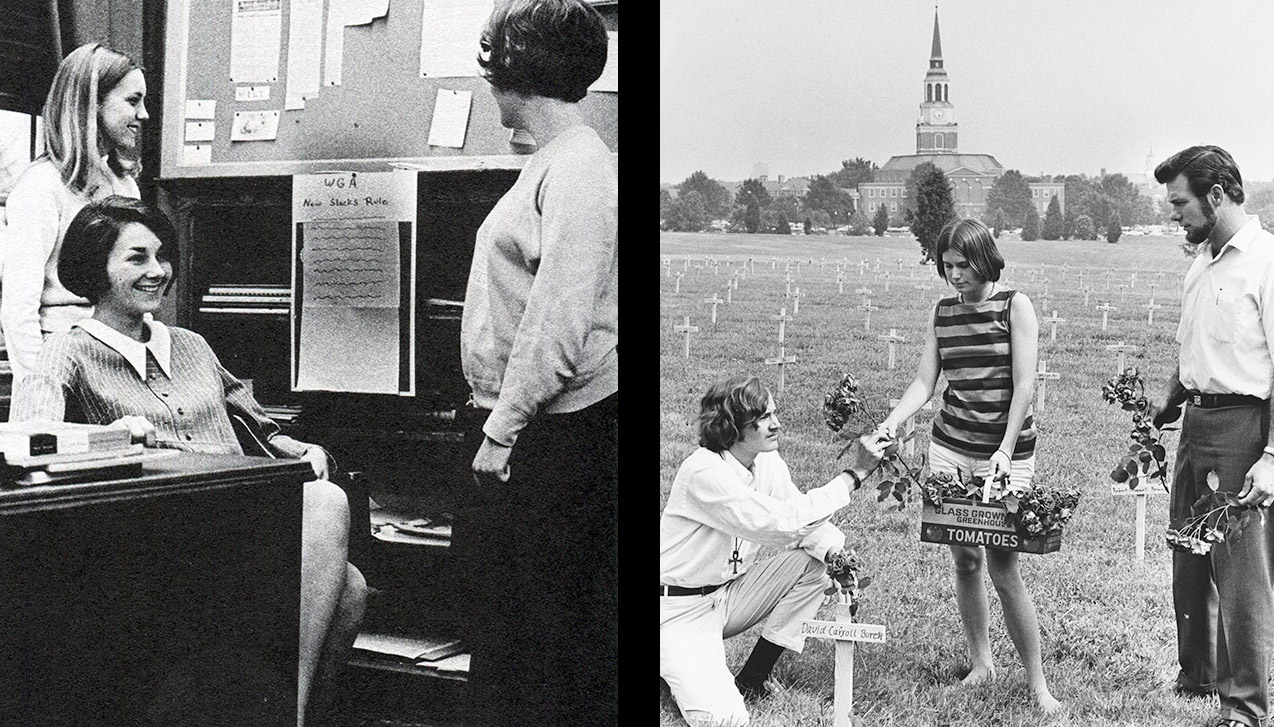

While street scenes were more dramatic across the country and had been for years, Wake Forest students regularly, but peacefully, protested the Vietnam War. (See more on the protests here.) In May 1970, more than 400 students marched to President James Ralph Scales’ on-campus house to oppose the war and present a list of demands, chief among them: abolish the ROTC program, reform the campus police department and end campus social rules. On Memorial Day, on the grassy field along Polo Road, students erected 1,200 small wooden crosses emblazoned with the names of North Carolina Vietnam dead.

Students also began linking opposition to the Vietnam War with support for civil rights and social justice. Black students formed the Afro-American Society in 1969 and sponsored the first “Black Week” to highlight inequities on and off campus, this at a time the University’s 2,500 undergrads included only 35 Black students.

By 1971, protests on campus largely faded. Students had claimed some significant victories in their top-of-mind quest to end outdated social policies. The dress code for women was abolished. Chaperones were no longer required for off-campus social functions. And women would no longer receive a “call-down” for failing to make their beds by 10 every morning. But intervisitation rules restricting “coed” visits to men’s dormitories remained for several more years.

What was it like being a student in those days? What lessons learned might help us navigate today’s societal turmoil and challenges? Wake Forest Magazine asked six alumni to reflect on their experiences from that time of upheaval. (Interviews, which have been condensed, occurred in September and October.)

(Jump to interview by clicking name)

-

Jim Cross (’70, JD ’73)

- Oxford, North Carolina

-

Alex Sink (’70, P ’11)

- Thonotosassa, Florida

-

Freeman Mark (’71)

- Boca Raton, Florida

-

Betty Hyder Stone (’70, P ’94)

- Mobile, Alabama

-

Al Shoaf (’70)

- Gainesville, Florida

-

J.D. Wilson (’69, P ’01)

- Winston-Salem

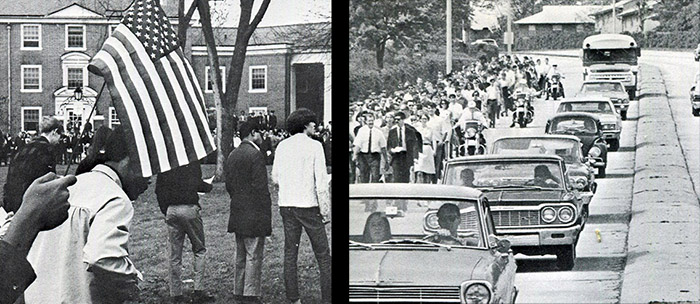

LEFT: A student protest on the Quad in 1969. RIGHT: Students march to downtown Winston-Salem to support efforts to address racial and social problems.

More than 400 students marched to President James Ralph Scales’ home in May 1970 to protest the Vietnam War and campus social and racial issues.

Jim Cross (’70, JD ’73)

-

THEN: Originally from Burlington, North Carolina

-

Student Government President, 1969-70

-

First student to serve on the Wake Forest Board of Trustees

-

-

NOW: Attorney, Cross & Currin LLP, Oxford, North Carolina

What do you remember about the late 1960s?

So much was happening between 1967 and 1970. I have memories of the last Homecoming football game played at Bowman Gray Stadium in 1967. Riots were occurring in downtown Winston-Salem. We drove from campus to the stadium single file and with a police escort. I remember seeing an Army jeep with a machine gun in the back. You didn’t grow up this way, at least not in Piedmont and rural North Carolina.

Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April of 1968. I heard about it during a Better Politics on Campus meeting held in the Reynolda Cafeteria. That was a horrible time. When school was out, I came home in June after a date with my future wife, Deb, to watch Robert Kennedy win the California primary. I went to bed excited about his victory. My mother wakes me up the next morning to tell me he had been killed. It touched most of America, but particularly the younger people. That triggered many painful emotions. A lot of saying, “What can we do?” and “How can we stop all of this?”

What was happening on campus?

During the late 1960s, positive things did happen on campus. There was a march from campus to downtown in 1968 as students and faculty sought ways to alleviate community problems. Students pledged to mentor children (in the community) and do other constructive interaction. Later, there were about 500 people in Wait Chapel for a celebration of Dr. King’s life.

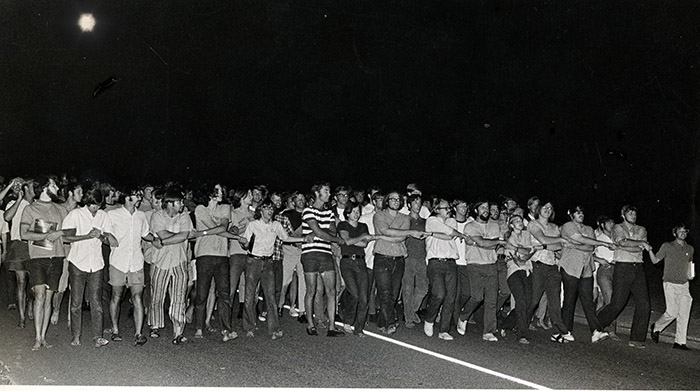

There was a war going on in Vietnam, causing much concern and response on campus, including our participation in the national Vietnam moratorium held at colleges across the country on Oct. 15, 1969. We had 1,600 people in Wait Chapel in our own version of a demonstration against the war. Later, students marched to Dr. Scales’ house to protest the Vietnam War and campus issues. Five hundred students held an evening vigil in front of Reynolda Hall in protest of the Kent State student killings.

One thousand two-hundred wooden crosses with the names of North Carolina Vietnam deceased were placed along the campus streets. You knew people who were there and who were killed. I had a fraternity brother, Forrest Hollifield (’68), who lost his life (in an air crash). He was one of the nicest guys I have ever met in my life. That really hit home. To this day, his death still greatly saddens me.

There were other issues. A car was buried (in front of Tribble Hall) during the first Earth Day celebration in 1970. There was the advancement of women’s rights led by our women students. The Afro-American Society was very active on campus. You had four different causes transpiring at the same time: racial relations and justice, the Vietnam War, the environment and women’s rights. If you couldn’t find a cause to support, something was wrong with you.

The causes, movements and activities energized Wake Forest. Not all of it was pretty, but it was good for us as a University to look at those issues, be involved and then be part of the solution. Certainly not all of the students participated. However, we had come a long way from protesting about not being able to dance on campus. We really grew up. Instead of looking inside, we were now looking outside. We were viewing the world, or at least our country, through a different perspective and searching for answers. We may not have had masses of people, but you regularly had students coming into Reynolda Hall and elsewhere on campus to express opinions ranging from concern to outrage. The late 1960s brought a life-changing experience at Wake, both individually and as a University family.

Are there comparisons to what is happening today?

There are certainly similarities between now and the late 1960s. There’s no question about the intensity of what is happening today, particularly with Black Lives Matter. There are different issues today, yet in a way they’re the same issues. What we learned at the time was you need to get involved. You need to be part of the solution, but you also need to do it the right way. And you can’t give up. You can’t have one mass demonstration and go home. The future leaders are on college campuses now. There are different viewpoints, and not everybody is comfortable with the same resolution. America definitely needs changes. Yet, we all need to pitch in and accomplish something constructive.

When you look back in history, 1968 has been judged to be the worst year in our country’s history. We have probably obtained that label in 2020. We have work to do. How can you make changes on campus? How can you make changes in this country? Let’s don’t be blue and red. Let’s be Americans. We can have different ideas and different viewpoints, but still work together.

And, we need to respect everyone’s opinion. We have a tendency today to make people good guys and bad guys. We need to get past that and look at what is best. Together, we can once again make a difference.

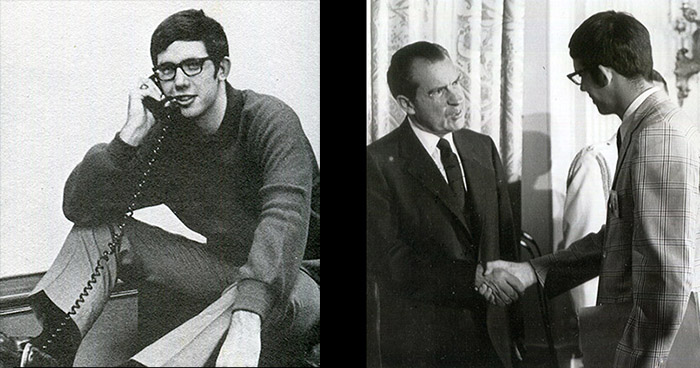

Cross met President Nixon at the White House during a reception for student government presidents and college presidents from around the country.

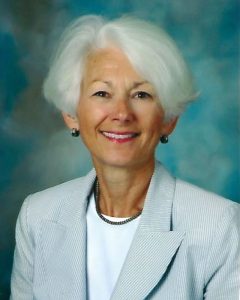

Alex Sink (’70, P ’11)

-

THEN: Originally from Mount Airy, North Carolina

-

NOW: Lives in Thonotosassa, Florida

-

Life Trustee, Wake Forest University

-

Distinguished Alumni Award recipient, 1993

-

Former president, Bank of America, Florida

-

Chief financial officer, State of Florida, 2007-11

-

What was Wake Forest like during your student days?

My class came to Wake in 1966; there were about 500 male students and 200 female students in my class. We were not a university yet; we were still Wake Forest College. Wake operated under a mantra of in loco parentis, in place of our parents. There was no dancing permitted on campus, much less drinking. Girls’ roles were different from boys’ roles. We were not permitted to wear pants across the street from the girls’ dorms. We had curfews. We had to sign in and out. We wore heels, dresses and gloves to football games.

My class came to Wake in 1966; there were about 500 male students and 200 female students in my class. We were not a university yet; we were still Wake Forest College. Wake operated under a mantra of in loco parentis, in place of our parents. There was no dancing permitted on campus, much less drinking. Girls’ roles were different from boys’ roles. We were not permitted to wear pants across the street from the girls’ dorms. We had curfews. We had to sign in and out. We wore heels, dresses and gloves to football games.

Wake sent us a book to read (the summer before freshman year), and I have to give Wake Forest credit for this, the book was “The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley.” Reading it was shocking to me. In some respects, reading that book has influenced the rest of my life. The author was Alex Haley, who years later wrote the book “Roots,” which became a television series. So here we are sitting around in a circle of freshmen discussing “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.” We were smart kids, but I didn’t know anything about this. In my junior year, Alex Haley was the featured speaker in the College Speaker Series. I got to drive over to the Greensboro airport and pick him up.

There was “consciousness raising” about Black culture, Black history, Black experience, even though our campus was almost totally white, and we were in the South. There was obviously an awareness that all these things were happening, but we were still in our bubble. We were a little conservative, and we weren’t going to go out and rabble-rouse too much. We weren’t even pushing back so much on those ridiculous rules about what coeds could not do.

In the summer of 1969, I enrolled in summer school at Columbia University. That spring, the students had taken over the administration building. So here I am in the midst of all this protest and activism. I would go down to Washington Square, which was the heart of the hippie territory, very much anti-war, anti-Vietnam, protesting, bell bottoms, smoking pot, and I’m thinking, “Boy, this is different from the world of Wake Forest.”

Like many other girls, I got married right after graduation, and we moved to Africa. I taught in a Methodist girls’ high school in Sierra Leone and international schools in Liberia and Congo. It gave me a perspective and a world view, and I’ve never been the same since. Once a week, I’d get Time magazine, and I read about bra burning and protests and equal rights and the feminist movement and Gloria Steinem. When I came back, I didn’t even recognize what was going on at Wake Forest. There had been not an evolution, but a revolution (on campus).

Do you see any similarities between the late 1960s and today?

It was a time of great angst in our country. The Vietnam War, the racial situation, the rise of the Black Power movement. It was a fraught time. It is a very fraught time now as well.

The biggest thing that I’m concerned with is who we are as a country. I think we have to do some soul-searching, and we have to learn to respect others’ opinions and to listen. And what I see instead is a lot of people in their corners who just stake out their position, and they’re not willing to walk in somebody else’s shoes. That’s why I think it’s so important with all the efforts we’ve made at Wake Forest to try and increase the diversity of our student body, to see whether or not we can encourage students to pick somebody different from them and learn how to walk in their shoes.

The Strings society from the 1970 Howler; Alex Sink is third from right, standing.

Freeman Mark (’71)

-

THEN: Originally from Elon College, North Carolina

-

Founder, Afro-American Society

-

Senior orator and Old Gold & Black Student of the Year, 1971

-

-

NOW: Attorney, Boca Raton, Florida

-

-

Founding partner (retired) at Washington, D.C.-based Mei & Mark

-

-

How did you end up at Wake Forest?

I’m from a farm family. My parents had eight children, seven boys and a girl. We all went to a one-room Black school and (later) to all-Black schools. In 1966, my principal, for some strange reason, selected a friend and me to go to Boys State that summer. I didn’t know what Boys State was, but it happened to be held at Wake Forest. It was the first integrated setting I had ever experienced in my life. The next year, when I had to decide where to go to college, what stood out in my mind was Wake Forest. I had been preceded by other Black students on athletic scholarships, but in my class there were about five or six of us who were not athletes. I think some of us were very isolated because we were not involved in athletics.

Why did you form the Afro-American Society in 1969?

We were not integrated into the whole campus. That isolation led to the formation of an informal group of just the Black students. Naturally we had negative experiences at times with professors and with other students and especially the Kappa Alpha fraternity. That gave us incentive to band together because they were overt in their racism. The Confederate flag was always flying from the (KA) windows, and the song “Dixie” would be sung at every football and basketball game. It made us stick together and watch out for one another. A lot of people thought that we were not going to survive academically. We didn’t have a Black professor on campus, so we needed an adviser to start the group. Dr. (G. McLeod) Bryan (’41, MA ’44, P ’71, ’72, ’75, ’82) promised us that he would be our adviser on the condition that if a Black professor came and we wanted to switch to a Black professor, he would wholeheartedly agree with that.

Do you recall any specific events that were traumatic?

I was walking on the Quad, and a professor’s daughter ran up to me and said very negatively, she was glad that (Martin Luther) King had been shot and killed, because he was nothing but a damn communist. Those were her words. And I never saw that in her before because she, and some of her friends, had befriended all of the Black students. And she said that with such venom and animosity. So I had two thoughts at the same moment: King’s death and her rejoicing over it. I’ve often thought of that since then, what provokes such hatred? And it dawned on me, this is who she really is and who he (her father) really is.

I read in the Old Gold & Black that you and nine other Black students, along with 13 white students, burned the Confederate flag and a record of the song “Dixie” on the Quad in November 1968.

We had a discussion as to whether any of the (Black) athletes should be involved. Some of them wanted to be, and we said no, we don’t want you to jeopardize your scholarship and have trouble with the University. I can’t remember burning “Dixie.” The aim was the Confederate flag. This Confederate monument thing (today) is not new; that’s been protested since before I was born. A lot of people were happy that we were doing it, and others were disgusted. I never forgot that I got a letter from a lady in Winston who disparaged me for having the audacity to burn the Confederate flag. If it did anything, it brought it to the surface, but probably more flags went up as a result. Those were exciting times. There was a lot of disharmony; as far as I know, there were no physical fights, but there were a lot of verbal ones.

Did you consider yourself an activist when you were a student?

There were many protests against the Vietnam War and during the riots of ’68. I didn’t participate, because any extra time I had, I studied. We were activists in the sense of getting things done, but not going out and marching and so forth. That was not me. I do not think I was ever one (an activist), but only a “reactionist” to what we as Blacks encountered. One instance, when I met Dr. Bryan for the first time, and it was my first time doing anything openly in the way of protest. It was immediately after the Martin Luther King assassination, and many Caucasians were opining that the race riots and burnings in U.S. cities were uncalled for and unjustified, and articles were being carried in papers to that effect, and one had appeared in the Old Gold & Black. I responded with a letter basically saying although one may not agree with the protest methods, certainly I could empathize and understand why it was happening. An antagonistic professor responded critically in a subsequent letter, and I replied in disagreement to his. After the letters ended, Dr. Bryan looked me up and applauded my writing and my confrontation of the professor’s position.

Did you personally face racism?

Constantly. But the beautiful thing is, and I want to hasten to add this, at the same time you found a lot of love and respect and dignity from Caucasians. The professors were less racist than students, but there were racist professors. I had professors that were dear professors, just wonderful professors. At the same time, you had those that you knew something was going on. There were more instances of acceptance by professors and students than rejection. We didn’t go there to be accepted or rejected, but Wake served a good purpose in our lives.

Do you have any advice for today?

I think that it applies from perhaps the time of Adam and Eve until now. Don’t let the negative rule you. Let the obstacles that you face cause you to excel. These were all things that we were taught in the Black community. Never give up and don’t be discouraged by things against you. Let them propel you. And always go back and help those from where you came. You have to do something for someone other than yourself. Those were the examples that we got from the wonderful educators who helped multiple Black students survive our Wake Forest experience: Dr. Bryan, Dr. (Franklin) Shirley, Dr. (James Ralph) Scales, Dr. (Ed) Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93), Dr. (Herb) Horowitz, Dr. (Merwyn) Hayes and Dr. (Julian) Burroughs (’51, P ’80, ’83).

The Afro-American Society from the 1970 Howler; Freeman Mark is at back center.

Betty Hyder Stone (’70, P ’94)

-

THEN: Originally from Kingsport, Tennessee

-

President, Women’s Government Association, 1969-70

-

-

NOW: Retired teacher, Mobile, Alabama

What do you remember about the late 1960s?

I lived in Bostwick dorm, and Dana Hanna (’65, MAEd ’71, P ’95) was the house mother. Her fiancé, Wally Dixon (JD ’72, P ’95), was in Vietnam. In those days, most of us didn’t have TVs in our rooms; we didn’t have computers or cell phones, no easily available current news, so I felt rather cocooned. But Dana had a TV, and we would talk about where Wally was and what was happening. She was on pins and needles, as we all were, because it was not a pleasant time. That was my source of information about the war.

I lived in Bostwick dorm, and Dana Hanna (’65, MAEd ’71, P ’95) was the house mother. Her fiancé, Wally Dixon (JD ’72, P ’95), was in Vietnam. In those days, most of us didn’t have TVs in our rooms; we didn’t have computers or cell phones, no easily available current news, so I felt rather cocooned. But Dana had a TV, and we would talk about where Wally was and what was happening. She was on pins and needles, as we all were, because it was not a pleasant time. That was my source of information about the war.

Anytime you have personal knowledge about what’s happening to people, it definitely changes things. And then Forrest Hollifield (’68), a fraternity brother of John’s (her future husband John Stone (’69, P ’94)), was killed. As an innocent, naïve person, I believed what people said. You believed the president. When My Lai happened (a massacre of Vietnam civilians by American soldiers in 1968) and (I saw) all the cruelty, it was an awakening for me.

What I remember most about 1968 was Martin Luther King’s assassination. I remember very vividly the chaos of that summer at the Democratic National Convention and Robert Kennedy’s assassination. We watched the convention every night and (saw) the protesting and marching and violence. It was terrible, very much like what we’re going through today, unfortunately.

A lot of guys at Wake were in ROTC. When the lottery started, I was student teaching at Reynolds High School. I wanted to teach the short story, “The Lottery,” by Shirley Jackson. One of the parents called because she thought it was about the draft (lottery). That was where everyone’s mind was.

Were you involved in any of the protests on campus?

The protests were never so disruptive that it interrupted anything close to me. I wasn’t a participant; none of my friends were, either. It wasn’t like we were ignorant or unaware or that we didn’t care. I guess I thought that protesting wasn’t the best way to respond to issues. I never felt intrigued enough by the idea that protests would lead to meaningful change. I always felt, sometimes with regret, that our campus was more protected or innocent than some of the larger schools that had more diversity.

What was the role of the Women’s Government Association?

The WGA advocated for more freedom. It was a big deal to wear pants to class or get a later curfew. I know that sounds quaint now, but those were big issues for us. Our social culture at Wake embodied the in loco parentis philosophy, and it was a protective place for girls. There was bubbling resentment about unequal pay and unequal opportunities. But we really haven’t solved that. The situation during this pandemic has been especially challenging for women who are working from home while supervising their children’s remote learning. It seems some employers still don’t appreciate those difficulties.

Are there any lessons that we can apply that you learned in the ’60s?

I’m thinking about all the political partisanship, which to me is just such a tragedy, because we have big problems to solve. I think relationships are the key to solving problems. If I know your story, and you know my story, I see you and I hear you in a whole different way. You take on dimension and depth that just a superficial read might not indicate or allow. If we could sit down together and I listen to your story and you listen to mine, we would have a harder time disliking one another.

If our leaders could embody that philosophy and approach some of these volatile situations and say, “Let’s talk.” If you can listen to people respectfully and try to gain some understanding of their perspective, it can change everything. In her book “Becoming Wise,” Krista Tippett says, “The most basic and powerful way to connect to another person is to listen. Just listen. Perhaps the most important thing we ever give each other is our attention. …” And, I believe that.

LEFT: Betty Hyder Stone, seated, in 1970. RIGHT: Students placed crosses on campus to symbolize North Carolina Vietnam War dead in May 1970.

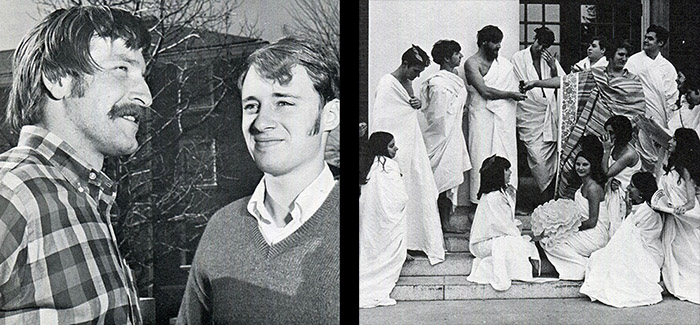

Al Shoaf (’70)

-

THEN: Originally from Lexington, North Carolina

-

Editor of The Student magazine

-

First Marshall Scholar from Wake Forest; also Woodrow Wilson Fellow and Danforth Foundation Fellow

-

-

NOW: Alumni Professor of English Emeritus, University of Florida

What was the atmosphere like at Wake Forest in the late 1960s?

Wake Forest was in a severe identity crisis that wasn’t resolved until many, many years later: Whether it was going to be a local, small college affiliated with a religious institution or whether it was going to be a different kind of institution with different aspirations, looking outward toward the world more. To oversimplify it, it’s the difference between a cosmopolitan and a parochial outlook.

Wake Forest was in a severe identity crisis that wasn’t resolved until many, many years later: Whether it was going to be a local, small college affiliated with a religious institution or whether it was going to be a different kind of institution with different aspirations, looking outward toward the world more. To oversimplify it, it’s the difference between a cosmopolitan and a parochial outlook.

In that context, even so, the concern that touched me most, at the same time as it did practically every other young man, was the draft. When the lottery went through, my birthday came up number 341, so there was no chance I’d be drafted. And you can imagine, it was like the weight of the world taken off my shoulders. This added to the aura of division among us. I associated with a number of young men who were getting commissions through ROTC. I remember several cases quite vividly, when, if you got into a discussion with them about patriotism and politics, they would turn against you if you had anything but the most absolute willingness to die for your country. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. (It is sweet and fitting to die for the homeland.)

On the other hand, there were people, I guess today we would say “liberal” or “left-leaning,” but that’s not what they and we called ourselves, who felt differently. We certainly weren’t Berkeley hippies. There was no cultural environment for that degree of alienation. But we weren’t young men willing to give our lives on a moment’s notice for the Vietnam War. We were not a significant percentage of the student population, but we weren’t a negligible minority either. What we were aware of is not so much hippiedom as the fact that there were alternatives, as there are many different ways of doing things, many different prospects for living one’s life. And that brought its own tensions. I found them mostly energizing and not in any way defeating.

How did that “identity crisis” affect what was happening on campus?

I remember when Timothy Leary (a proponent of LSD who was also known for the phrase, “Turn on, tune in, drop out”) came, and lots of people turned out for him. I remember several people who did everything they could to get enough money to go to Woodstock. At the same time others just avoided it, paid very little attention to this kind of, let’s call it energy. Sometimes the energy was fairly muted, but a lot of the time it was anything but.

We had the moment of the terrible starvation in Biafra (during its failed attempt to separate from Nigeria). We had a number of students raising money, raising awareness, trying to get food to those who were starving. It was a small-scale commitment perhaps compared to Berkeley or such campuses, but it was just as intense. People were just as committed to issues of social justice and looked for ways to express their commitment. They were not so much interested in starting riots as they were in trying to coordinate efforts to change things. From where I stood, this was a minority but a very vocal minority. And to the credit of the institution, these students and the faculty who supported them were recognized and helped in ways that at least were available to help them.

Do you see any comparisons between now and then?

I do. Many people were resigned to voting for Nixon because he kept promising there would be no more Vietnam War. And that was the candy stick that he held out. And it was effective. It was a time of serious political dissatisfaction and disillusionment. And disillusionment is the word I would use for now. The disillusionment now is, I think, worse, but I say that hesitatingly because it felt pretty damn bad back then. We knew then as we know now that politics are corrupt. We were younger and perhaps naïve, but we were not so naïve as to be blind to the corruption. And I suppose that I feel, in that particular line of historical reflection, that I guess I would say nothing has changed, and it has gotten worse.

LEFT: Seniors Al Shoaf, left, and Melvin Whitley, both Woodrow Wilson Fellows. RIGHT: The staff of the 1970 Student magazine; Al Shoaf is at center left.

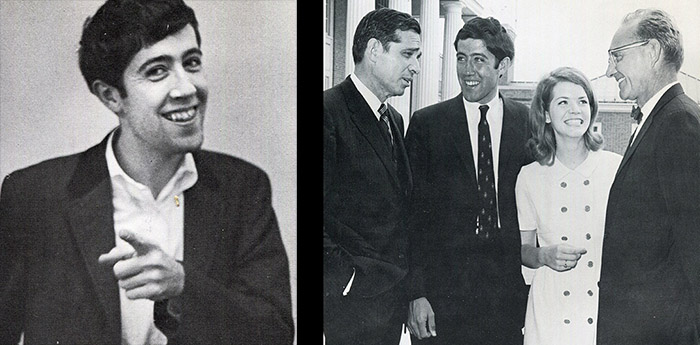

J.D. Wilson (’69, P ’01)

-

THEN: Originally from Mount Sterling, Kentucky

-

College Union president, 1968-69

-

Old Gold & Black Student of the Year, 1969

-

Director of the College Fund and associate director of Alumni Affairs, 1969-70

-

-

NOW: Founder and former president; chair and CEO, Excalibur Direct Marketing, Winston-Salem

-

Founder and managing partner, Stepstone Strategic Partners, LLC

-

Founder, president and treasurer, Creative Center of North Carolina Inc.

-

Do you see comparisons between what happened in the late 1960s and today?

Look at the Old Gold & Black from March 18, 1969, and there are four articles that capture what was going on. It’s almost like déjà vu. (Articles include the formation of the Afro-American Society and Challenge ’69, a symposium that included speeches by Sen. Edmund Muskie, D-Maine, and community activist Saul Alinsky.)

Look at the Old Gold & Black from March 18, 1969, and there are four articles that capture what was going on. It’s almost like déjà vu. (Articles include the formation of the Afro-American Society and Challenge ’69, a symposium that included speeches by Sen. Edmund Muskie, D-Maine, and community activist Saul Alinsky.)

Challenge ’69 was about the urban crisis. Wake Forest was not standing on the sidelines but doing something about it by bringing thought leaders of the day to campus to talk about social injustice, the economy, racial inequality — the same issues we’re talking about today. It was the kind of hard stuff that we needed to be learning about and thinking about. (Dean of Men) Mark Reece (’49, P ’77, ’81, ’85) and (Provost) Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) and President (James Ralph) Scales were guiding us.

We also had a symposium in ’65 and ‘67. Challenge ’65 was about Black inequality. In 1967, they brought in George Lincoln Rockwell, the leader of the American Nazi Party. (Some Black and white students walked out of Wait Chapel in protest of Rockwell’s speech.) My first thought was, “Why is Wake Forest allowing somebody like this on campus?” But then I realized you do it because you bring controversy to the table to discuss and learn and not be ignorant. That was one of the blessings of the way Wake Forest did it. It used intellectual curiosity and dialogue and freedom of speech to bring prominent leaders to campus.

Some people like to say Wake Forest was a bubble. It was kind of a bubble, but it was not without meaning and engagement and involvement. Through things like the symposium and College Union lectures, Wake exposed us to the Big Bad World or the Great World of Opportunity; which is it going to be?

In that same issue (of the OG&B), there are letters from Black students. They had just formed the Afro-American Society, sort of a version of Black Lives Matter. So again, déjà vu. They had been encouraged to do that through the social unrest throughout the country and on college campuses, not only about Black inequality, but the death of Martin Luther King, John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy, as well as the Vietnam War. We learned to protest appropriately; we learned to speak up; we learned to work to change things.

You were one of the students who went to New York in 1969 to purchase art for the then-new College Union Collection of Contemporary Art; does the art purchased that year reflect the times?

There were some subtle things about the times we were living in: protest, sexual revolution, anti-war, question the military, question patriotism, question nationalism. Take Jasper Johns, my favorite artist of that collection and my favorite work. Presenting the flag the way he did in orange and green and gray, and then the visual trick that you see red, white and blue, wow. I remember thinking when I saw that orange and green flag how unpatriotic. And then you see it change. That whole experience with that work of art is to take a symbol that we take for granted, and maybe we need to think of it in new ways. There was a lot of art that dealt with social injustice, power and the powerless threaded through that collection.

What lessons did you learn during those times?

Be involved, try to help, try to make a difference, constantly learn and listen, listen, listen. Listen to others, (be) very diverse and inclusive in every way. I believe the more you embrace diversity of people and opinion, the stronger fabric of humanity you become, and you are better able to see the world how it might be and help get it there.

I just hope we can get through whatever’s coming as well as we did then. Again, if you look at some of the art in 1968-69, some of the message is uncertainty. What’s going on? Where are we going? What’s happening? If we can find creative ways to get through whatever’s coming, God bless us.

LEFT: J.D. Wilson in 1970. RIGHT: President James Ralph Scales, from left, with seniors J.D. Wilson and Norma Murdoch and medical school dean Manson Meads.