As Yadkin Riverkeeper, Brian Fannon (’89) leads efforts to protect and enhance the river.

Fog hovers in the valleys and curls around the low mountains of Wilkes County, North Carolina, on a mid-September morning. Five miles ahead, down Red White and Blue Road, lies a put-in for kayaks and canoes.

This is a good day, pleasantly cool, to paddle the Yadkin River, to see herons and mink and the banks of Roundabout Farm, settled by a Revolutionary War hero.

It’s the best kind of day for Brian Fannon (’89), who holds the romantic title of Yadkin Riverkeeper. “It looks like the water might be down enough for us to go paddling,” Fannon says. He has set up the trip to share his work and the river’s history with Wake Forest Magazine.

It’s the best kind of day for Brian Fannon (’89), who holds the romantic title of Yadkin Riverkeeper. “It looks like the water might be down enough for us to go paddling,” Fannon says. He has set up the trip to share his work and the river’s history with Wake Forest Magazine.

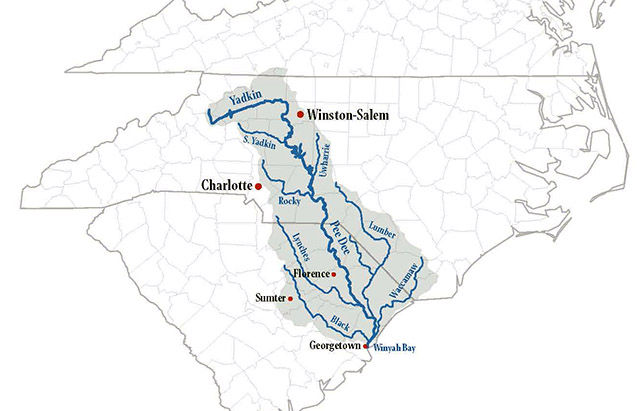

Fannon’s job with the Yadkin Riverkeeper nonprofit is to monitor and help sustain the quality of the Yadkin-Pee Dee River Basin. It’s the water source for Winston-Salem and most of central North Carolina. He takes samples and tests the river regularly. He and Executive Director Edgar Miller work with state officials, developers, landowners and farmers to protect the watershed and wildlife from runoff and pollution.

He relishes these times when he can leave behind the computer and the phone for a serene day on the stream, where living trees reach into the sky and fallen ones form ghostly gray sculptures along the banks.

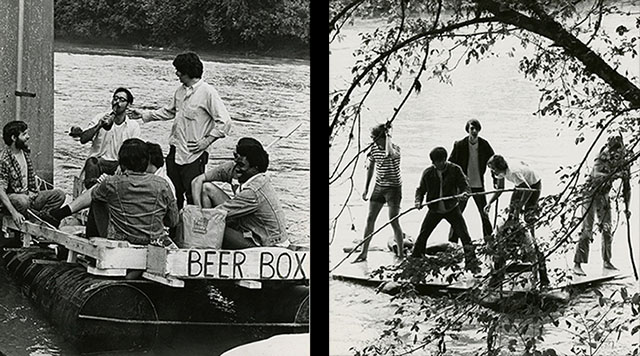

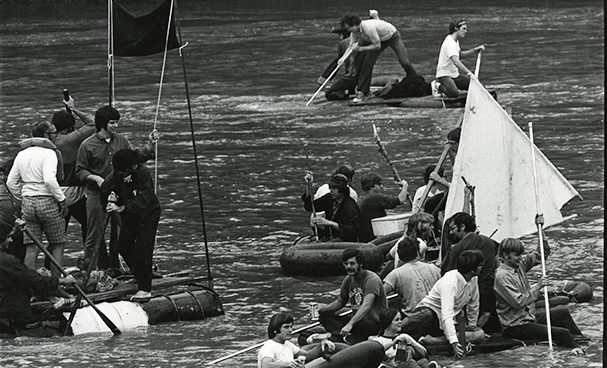

Many Deacons remember the Yadkin for annual wacky rafting races and beer-filled afternoons floating on the shallow river. But townsfolk in Winston-Salem tend to forget about the Yadkin or never learn its charms, Fannon says, because it’s 15 miles away. Unlike rivers that gurgle through some cities, the Yadkin doesn’t impose itself on the daily landscape for most of the 800,000 to 1.6 million people it supports across North Carolina and South Carolina.

The annual Men’s Residence Council race inspired creative ways to float and drink beer, or drink beer and float on the Yadkin. Far left, the biology department, well before Brian Fannon’s time, fuels up for the race, from the Old Gold & Black on Oct. 4, 1974. Others took a flat-bottom-and-tire approach (below).

Fannon points out that the human body is about 70% water. That means if you live and eat and drink at Wake Forest, “you are, in fact, 70% Yadkin River,” Fannon says.

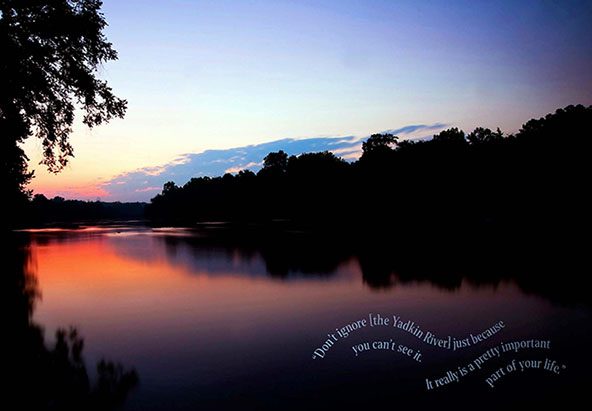

“You are nothing more than a vessel for hauling around part of the Yadkin River for a few years,” he adds, one of his many deadpan quips. “Don’t ignore it just because you can’t see it. It really is a pretty important part of your life.”

Mountain Man

Conjure an oil painting of a man called “the Riverkeeper,” and it surely resembles Fannon. With his untamed gray hair, full beard and stocky tree trunk of a frame, he appears more Jeremiah Johnson come down the mountain than Dr. Fannon, the biologist with a doctorate in biogeography and fluvial systems. Yet he is both, and more.

He did, indeed, come down the mountain, the Blue Ridge variety. His family farmed tobacco and raised cattle in Avery County, North Carolina, near Beech Mountain. “I grew up pretty much in the woods running around like a wild heathen,” he says in his gentle twang.

His house was the last on the electrical line, a half mile from the nearest neighbor, his uncle, and another half mile to the next home. Lightning came down the line and grounded through his house, “and that was always exciting. We would sit in the stairwell during bad thunderstorms to stay away from exploding lightbulbs,” he says.

In his senior year of high school, “I was a little bit, I guess, behind the curve.” He thought the guidance counselor’s office took care of college applications, so when “everybody started getting their acceptance letters, I’m like, ‘What exactly is going on here?’”

Like so many Deacons, Fannon has a knack for navigating unusual currents to reach a destination he hadn’t visualized but which, in the end, suits him just right.

He finagled late acceptance as a freshman at Appalachian State University because he had serendipitously registered there during his junior year of high school. He had shown up for a presentation on becoming a DJ at the radio station, only to discover that it was a college course. “A couple of graduate students in the communications department said … ‘Look, we’ll fix this,’” Fannon says. One met him at the gym on registration day and walked him through signing up as a non-degree-seeking student.

“I really appreciate what they did for me,” he says. “It showed me that you can do pretty much anything, if you can just figure out how to do it.”

Fannon had friends at Wake Forest who loved it, and he wanted to study ecosystems and aquatics in the Department of Biology, so he transferred his sophomore year.

One of his friends was studying theatre, another draw because Fannon had worked since high school at the “Horn in the West” Revolutionary War-era drama in Boone, North Carolina. He was an usher at the outdoor amphitheatre, and one night “they decided they needed a spare dead body after the last battle scene,” Fannon says. “(They said) ‘Can you just come backstage and put on a red coat and go die?’ So, why not?”

The next year, he worked as a technician and space filler on stage, eventually becoming a master carpenter and, even more fun, a pyrotechnician, taking care of firearms, explosions and cannons. Until a few years ago, he continued to pinch-hit for “Horn in the West” because he was one of the few people who could repair the 1980s turntable critical for rotating sets.

Wake Forest cemented theatre as a life passion. He never appeared on stage — “I act up occasionally, but I’m not an actor” — but he built sets for almost every show for two years. Later, theatre helped him land a job in the wilds of Alaska that he never expected to snag.

The Yadkin-Pee Dee River Basin spans 21 counties. About half the watershed is forestland, mostly owned privately. Nearly one-third of the watershed is used for agriculture. Thirteen percent of the land is developed, a figure that is rising rapidly, according to the Yadkin Riverkeeper nonprofit.

History on the Banks

Fannon fishes every rare chance he gets, but as a biology major at Wake Forest he set neither foot nor fishing rod into the Yadkin during his three years on campus. He had grown up on the pristine Watauga River, and the Yadkin was too dirty, he says, though he did collect plant samples there for a class. Today, the Yadkin is much cleaner than it was 30 years ago, Fannon says.

When he became Riverkeeper, the nonprofit’s float trips were attracting 100 paddlers at a time. Lugging so many boats and people in and out of the river made for a strenuous day, and the nonprofit didn’t want to take business from outfitters. It lowered the limit for Riverkeeper paddles to 20 people, allowing time for explanation and exploration.

On this September day, clear water gurgles across the rocky bottom at the Roaring River Canoe Rentals launch site. The Roaring River is a tributary that joins the muddier Yadkin a short distance downstream. Photographer Christine Rucker, a Yadkin River junkie who has a house on its banks, shares a canoe navigated by Riverkeeper board member David White, a marketing and communications professional who is an amateur historian. Fannon and I each paddle a kayak for the three-hour trip.

White and Johnny Alexander, the owner of Roaring River Canoe and a native of the area, share stories before Alexander sees us off. A big stretch of our trip will wind along Roundabout Farm, more than 1,300 acres of farmland originally settled by Col. Benjamin Cleveland, who led the Wilkes County militia at the pivotal Battle of Kings Mountain in the Revolutionary War. We will pass what is known as the Hanging Tree on Roundabout where Cleveland, known as “the Terror of the Tories,” executed British loyalists and, Alexander adds, horse rustlers. “He’d hang you in a minute.”

David White, a Yadkin Riverkeeper board member, wears his “Sheriff of the Shoals” hat, as he is known for his passion for protecting the river.

(This stretch includes the irresistible ghost tale of a red-coated rider, some say headless, atop a white Arabian stallion galloping along the banks at Bugaboo Creek. Cleveland rode home to Roundabout on such a white horse as a war prize claimed from the British commander killed at Kings Mountain.)

The war history of this stretch of the Yadkin around the town of Ronda helps make it a favorite float for Fannon. He dreams of creating a living history museum along the Yadkin. For fun, he makes 18th-century tools, nails and leather bags and trades them with fellow hobbyists.

“In a different lifetime I would have become an anthropologist focused on tools of the 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th centuries and that progression — as the metalworking got better, the tools got better, and because the tools got better, the techniques of working changed,” he says.

He regularly takes part in Revolutionary War reenactments — always as a British soldier. “First of all because one of my ancestors actually was a Tory and was hated for burning down a lot of stuff,” Fannon says. “But second, more practically, you get invited to a lot more reenactments because everybody needs somebody to shoot at.”

Fish Weirs and Beaver Dams

Fannon’s love of history and biology inspires his appreciation of the Yadkin’s rich lore. Archaeology teams from Wake Forest have recovered remains of tribal life around 1000-1600 A.D. along parts of the river. The region was home to the Catawba, one of several Siouan language tribes in the Carolinas.

As we float along the greenish-brown flat waters, White points out a fish weir, a stone structure built by Native Americans in the shape of a V, with a basket or net at the apex to catch fish. This stretch holds two of 30 to 40 visible weirs on the Yadkin ranging from 500 to 800 years old, White says, but many are under water and no longer visible. Even though the river is sometimes so shallow we must navigate around rocks to avoid grounding, the Yadkin of earlier centuries was even shallower.

The beaver dams that Fannon studied — “playing in the water again” — for his doctoral dissertation at UNC Greensboro shed light on why the river is so shallow today. He analyzed how beavers engineer such durable structures and how they affect streams over decades. “Always they’re professionals; they do it for a living,” he says.

“The final most important conclusion was that before Europeans settled and beaver fur became a major commodity and they wiped them out pretty much, beaver would have been one of the primary controlling factors on stream form in North America,” Fannon says.

Beavers built numerous dams on the river and tributaries, abandoned them, then recycled them. The dams slowed the flow of water and sediment and kept flooding to a minimum. With fewer dams, the silt that flows unimpeded has created problems. It covers the riverbed, carries pollutants and alters food sources and the spawning patterns of fish. Native Americans would not recognize the flooding we see today, Fannon says.

Bears, Moose, Fish and Maps

Fannon’s career path to caring for the easygoing Yadkin River began with years of exploring the wilderness of Alaska after his graduation from Wake Forest. Eventually he settled back home to be closer to his aging parents and to pursue graduate degrees.

Fannon says one of the things he appreciated about Wake Forest was “the students and the faculty tend to be very creative people.” He could study both biology and theatre, which almost became a double major.

He says his theatre experience landed him his favorite job: a summer counting sea otters and sea lions on an island in Prince William Sound in Alaska, two hours by boat from civilization. He had always dreamed of Alaska and applied for the research gig aimed at determining whether salmon nets were harming sea mammals. (They weren’t; fishermen were quickly cutting nets to free animals, which spared damage to creatures and nets.)

Fannon says competition for the job was stiff, and he asked the hiring company’s owner why she chose him over more experienced candidates. She had an avid interest in theatre. “She said, ‘I knew that living in the field camp, you were going to have a lot of challenges and not a lot of resources to fix them. And I figured if anybody could do that, a theatre tech could,’” Fannon says.

The days of endless sunlight allowed for endless fishing and exploring. Fannon knew he and his research partner would have no escape from each other on the small island. “We joked that by the end of this summer, we will be best friends or one of us will be gone. We are still very close friends.”

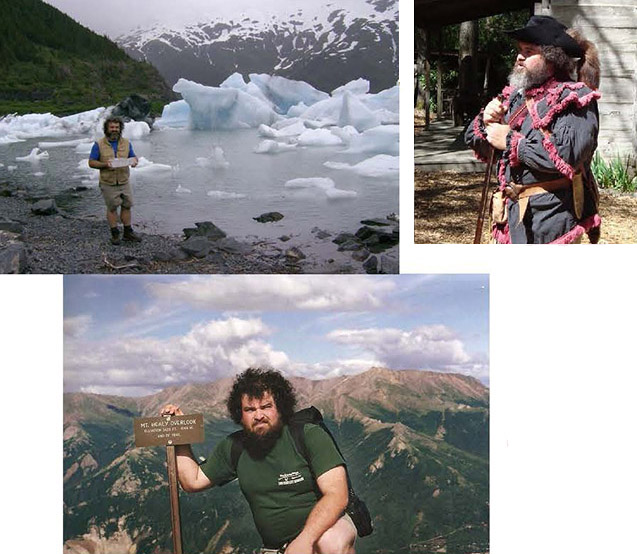

Brian Fannon’s past adventures include Revolutionary War re-enactments (top right), Alaskan ice and Denali National Park & Preserve.

He meant to stay only a few years in Alaska but kept returning there between positions on the East Coast — restoring American shad in Pennsylvania, surveying fish populations in Massachusetts, interpreting and managing at the Southern Appalachian Historical Association in Boone and consulting and mapmaking as a surveyor.

He discovered that he loved being at sea. He worked on a commercial fishing boat out of Kodiak in the Gulf of Alaska, seeing remote harbors that few tourists or even most Alaskans ever see. The pay was $100 a day, a lot in the 1990s for a young man in his 20s.

He managed tour operations at Denali National Park & Preserve, often ending up alone under the majestic 20,000-foot peak at 2 a.m. to pick up buses, and he liked the magic of those nights. His bear encounters were benign. “Talk to the bear, yell at it, wave your hands. The bear looks at you,” he says. Moose were not so friendly. He once made a frantic 100-yard dash to an open bus, with a territorial moose in hot pursuit.

In 2004, he came home to earn a master’s degree in historical geography at Appalachian in 2006. He worked at a theatre rigging company in Georgia as a set builder, driving back and forth to UNC Greensboro to work on his doctorate, which he completed in 2015. “I finished my dissertation in the machine shop in Georgia,” he says.

Sharing the Knowledge

As Fannon points out the Yadkin’s sites, he demonstrates the love of teaching he has developed, from kindergarten to university level, at UNCG, Appalachian, Salem College, Winston-Salem State University, the Allison Woods Outdoor Learning Center in Statesville, North Carolina, and more. When a colleague invited him to teach students about science in Kenya, “my response to the email was, ‘Let me think about it. Yes. When do we go?’ That’s how I got to do a lot of the fun things in my life is to just say, ‘Yeah, I’ll do it. When are we going?’”

Ashley Wilcox (MBA ’21), president of the Riverkeeper board and assistant director for the Sustainability Graduate Programs at Wake Forest, says Fannon is a master teacher.

“He’s talked to law school classes. He’s come to talk with some of our graduate school students, and at the same time he can … walk into a second-grade classroom and have the ability to share and break those larger concepts down to an easy-to-understand way,” she says.

Fannon brings both a country sensibility and scientific expertise in working with people to find grants and learn new methods for keeping pollutants out of the river, Wilcox says.

“He’s so approachable,” she says. “He’s really great at forging those relationships with people who may have … seen us as more of an enemy than an ally.”

Birds and Cows

The quiet of the river, punctuated by the caw of ravens, is soothing as we paddle under rust-colored bridge trusses. Fannon suggests avoiding paddling close to the bank but reassures us that those stories of snakes dropping from a limb are rare, and venomous copperheads don’t care for climbing trees, he says.

We pass a long stand of sensuous green bamboo forest, planted in the 1700s. Herons with stick legs perch among twisted tree limbs that have washed downstream and lodged in the mud. Blue kingfishers swoop across the river, landing on tree trunks that grow horizontally from the bank, like a photo that needs rotating.

A bald eagle flies by. A yellow-bellied slider turtle rests on a log. A brief rain shower leaves us damp but not drenched.

Like a funny image from a children’s book, a black cow stands chest deep in the river, staring at us. The Riverkeeper would rather see a fence to keep the cow and its mates from eroding the bank and depositing manure in the Yadkin.

Like a funny image from a children’s book, a black cow stands chest deep in the river, staring at us. The Riverkeeper would rather see a fence to keep the cow and its mates from eroding the bank and depositing manure in the Yadkin.

Fannon sees an abandoned red plastic gas can, and he paddles to the bank to see if he can get to it. He does, and he’s happy. It’s new and in good shape. “I really like that spout,” he says.

Our day ends at the boat launch in Ronda, a convenient 10-minute shuttle back to the Roaring River launch, despite the hours-long meandering path of the stream.

Everyone is smiling, including Fannon. He has removed a bit of debris. He has savored and shared the beauty and history of the Yadkin.

It’s been a good day on the river he keeps.

For more information on the Yadkin River and the Yadkin Riverkeeper nonprofit, go to yadkinriverkeeper.org.