Karen Baynes-Dunning (’89) outside her home in Greenville, South Carolina. She has held many roles — a lawyer, a judge, a social justice activist and an advocate for children and families.

Percy Baynes, 87, sits on the porch of his family’s retreat center in Caswell County, North Carolina, and points left to a stand of loblolly pines across a dirt road. That’s the place, but it’s gone now, his childhood home — the one-room log cabin with its lean-to kitchen, no electricity, no running water and an outhouse 50 yards from the back.

Like millions of Black men and women during the 1900s, Percy, motherless at 3 and an orphan at 16, joined the great migration from the South in search of a better life, away from violence and racial oppression. It was 1950. Percy was 17, with no way of knowing he was destined for college and a career contemplating the cosmos.

Percy Baynes points to the stand of trees where his childhood log cabin once stood. Photo by Maria Henson

A 15-minute drive from the porch is the brick house where Percy and his wife, Dorothy Totten Baynes, 86, live in retirement. They are content to watch hummingbirds, listen to podcasts and survey the land on which Dorothy’s parents tended fields and worked tobacco for two white sisters who never married and, to Dorothy’s mind, showed her parents barely a kindness until the last living sister shocked them all.

This is a story of the Bayneses’ youngest child, Karen Baynes-Dunning (’89) of Greenville, South Carolina. To begin to understand how Karen became a lawyer, a judge, a social justice activist and an advocate for children and families, one must start here in Caswell County with its county seat of Yanceyville, 25 miles from Burlington, North Carolina, and 14 miles south of Danville, Virginia. Here, most summers and on weekend getaways from Wake Forest, Karen would visit the land of her grandparents, Beatrice “Mama Bea” and Waymond “Daddy Waymond” Totten. She also tramped the other property, the one that Percy’s grandfather bought — shockingly for the times — from a white man in 1914. That is where the Baynes Family Farm retreat center sits today. It sleeps 16 and is available to rent for overnights, conferences, reunions and weddings, and, Percy points out, to people of all creeds, races and religions. Even though the log cabin of his birth is gone, for him the 90 acres represent “a return to the launch site.”

A photo of Percy Baynes’ birthplace appears in his memoir, “Return to the Launch Site.” Photo by Maria Henson

Over at the Totten farm, Karen shadowed her grandmother and namesake (Karen’s middle name is Beatrice), learning life lessons.

“It’s just something about them, even to this day,” says Dorothy about her daughter and the late Mama Bea. “When (Karen) needed to find a place of peace, this is where she would come.”

In conversations on Zoom, Karen in her big stylish glasses is quick to smile and laugh. She speaks joyfully of her days as a city girl, born in Washington, D.C., raised in Silver Spring, Maryland, but cherishing visits to the Totten farm with her three siblings. “That’s what the farm symbolized to us, especially throughout our childhoods, just running through the woods and being free and … being a kid,” Karen says.

To this day, she knows how to quilt, boil preserves and can vegetables the way her Mama Bea taught her. She speaks admiringly of how her grandmother served as an informal foster parent to hungry children, and to this day she lives Mama Bea’s final pronouncement. “The day before she died, she called for us,” Karen says. “And when I say all of us, there must have been 60, 70 people in the room,” counting cousins, aunts and uncles. “And basically, she gave her last sermon. And I remember it, because she said, ‘Take care of the children. … Not just the children in your own homes but all the children.’ And that’s just who she was.”

In her 30s beside the deathbed that day, Karen already had been answering Mama Bea’s call, at home and in what she describes as “my nonlinear career path.”

“Daddy Waymond” and “Mama Bea” Totten nurtured Karen’s love for country life, and from it grew her global view of social justice.

When Percy set out for Washington, D.C., he left a place of few opportunities for Black men beyond sharecropping. He left a county notorious in North Carolina history but not mentioned in the lessons I learned in public schools in the 1970s nor referenced on the county’s Wikipedia page even today.

Black residents in the rural South had few options to make a living other than sharecropping or working tobacco. Dorothea Lange photographed this son of a sharecropper “worming” tobacco in Wake County, North Carolina, in 1939.

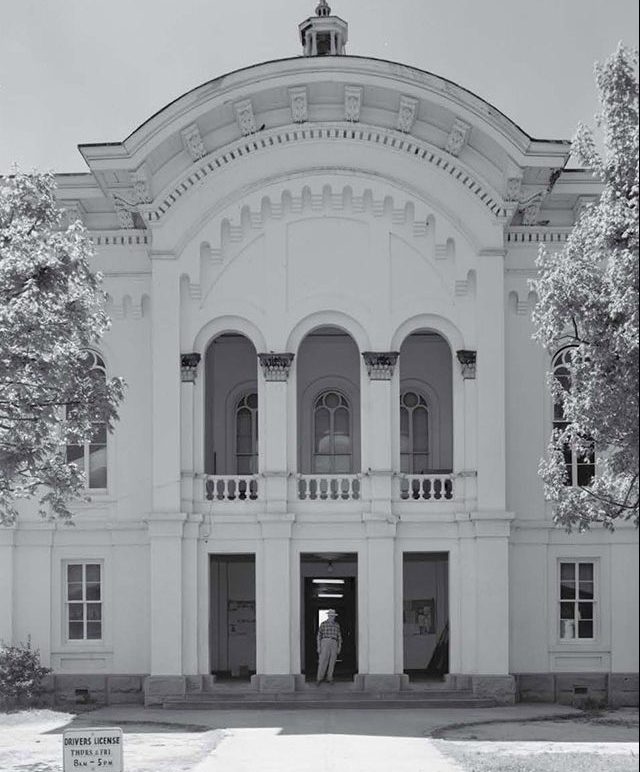

The years after the Civil War were meant to offer freedom and rights of citizenship to formerly enslaved men. The backlash from white supremacists was swift, marked by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. In 1870, nine years after the birth of Percy’s grandfather, a Klan mob decided to punish a white Republican state senator, John W. Stephens, who championed the rights of freedmen. They took him to a room in the courthouse in Yanceyville, tied a noose around his neck and choked him, then stabbed him three times, twice in the neck and once in the heart.

“(M)urdering a state official in broad daylight in a courthouse, generally a place where people expected justice — emphasized the power and arrogance of North Carolina Klansmen,” writes historian Jim D. Brisson.

The state Supreme Court in Raleigh required bail for three men arrested and wrote: “No motive is assigned for this murder, except ‘political animosity.’ The circumstances show it was done on premeditation, with fatal skill, and by a number of conspirators, (either taking part in the killing, or else keeping watch, and being on the lookout,) to whom the unsuspecting victim was led up for sacrifice.” No one was punished. A Klansman’s deathbed written confession in 1919 — only released years later — laid out the Klan’s role.

Stephens’ lynching and that of Wyatt Outlaw, a Black town commissioner in neighboring Alamance County, served as catalysts for Gov. William W. Holden to declare martial law to quell Klan violence in the Piedmont region. Holden paid the price for challenging white supremacy. In 1871 he became the first governor in U.S. history to be impeached and removed from office. (The state Senate pardoned him in 2011.)

A year after Percy left for Washington, Yanceyville drew national attention again when a black farmer named Matt Ingram was arrested and convicted on assault charges (at first charged with rape) after a young white woman said he had “leered” at her, frightening her.

The state Supreme Court struck down the conviction in 1953. Ingram throughout denied any ill intent. The justices wrote that he may have had “a sinister purpose” or “looked with lustful eyes” but ultimately concluded: “We cannot convict him of a criminal offense solely for what may have been in his mind. Human law does not reach that far.” Karen refers to the case sarcastically: “Yeah. ‘Old evil-eye Ingram.’ Ebony did a piece about it.” Time magazine did, too, headlining its article, “Assault by Leer.”

Jack Boucher’s photograph of the historic Caswell County Courthouse in Yanceyville, North Carolina, the scene of a lynching in 1870.

Percy found his bright future away from Yanceyville. Not only did he earn his B.S. and M.S. in mathematics at Howard University, but he also landed a job at NASA. He developed expertise in on-flight software for the space shuttles and rose to executive director of NASA’s orbiter division. In 1984, he left for private industry, joining a defense contractor as director of software engineering. By his side was the woman who had been his friend since they were teenagers in Caswell County, Dorothy Totten, a schoolteacher. She became his wife and the mother of four children. At home their lives centered around church in D.C., family and community service, with a faux-wood-paneled station wagon to take them anywhere they pleased.

Karen, the youngest, helped her dad with such projects as Meals on Wheels or fixing houses for the elderly. On some Christmas Eves they assembled bicycles and wrapped toys for children whose foster father was a local judge. The scene was “loving chaos,” Karen says, and this introduction to the “formal” foster care system would figure in her lifelong mission.

Dorothy says Karen was her “little angel” who talked all the time from age 3, stood up for kids who were bullied and believed she could do anything. Percy came home one day with a new suit and pants that needed altering. Dorothy instructed him to find a professional. “And the next thing I know … he’s tried them on, and (Karen, then in junior high) measured, and she did it,” Dorothy says. “ ‘Karen, have you ever done that before?’ ‘No, but I can do it.’ That’s just how she grew up.”

‘Karen, have you ever done that before?’ ‘No, but I can do it.’ That’s just how she grew up.

— DOROTHY TOTTEN BAYNES, Karen’s mother

She attended high school with mostly white students and, her mother says, made no distinction about race in her friendships. When it came time for college, she was recruited by several universities and received the offer of a full-ride Benjamin Banneker Scholarship from the University of Maryland. As an additional incentive in favor of Maryland and perhaps a destiny in physics, her father offered a Mazda RX7. Karen passed on the fatherly bribe and chose Wake Forest instead.

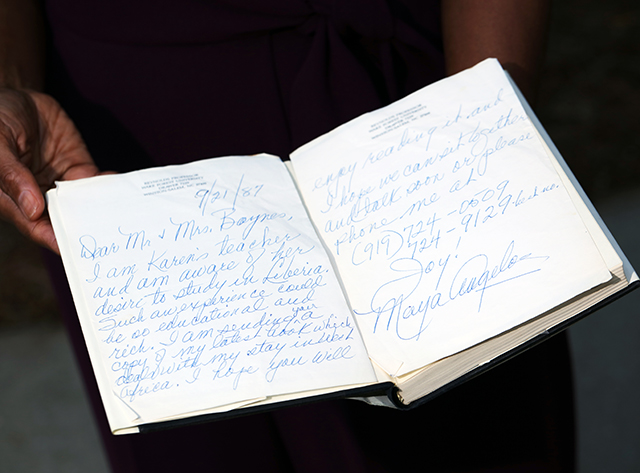

The beauty of the campus attracted her, but the big draws were Mama Bea nearby and the chance — with no guarantee — to study with Reynolds Professor of American Studies Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77).

“I took her class in the fall of ’87,” she says. “From Day One it changed my life.” The class examined African culture in the United States and returned repeatedly to Roman playwright Terence’s quote: “I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me.” Angelou would read a poem or break into song or have the class sing songs of the civil rights movement amid myriad surprises in her living room.

“One day the doorbell rings, and it’s Alex Haley,” Karen says with an abiding sense of awe when remembering the author of “Roots.” (After Haley died, his farm in Tennessee became a Children’s Defense Fund retreat center — “Where we grow justice” — in training the next generation of advocates for children and families, including Karen. It later inspired the Baynes Family Farm’s mission.)

Attorney Neil Stanley (’89) of Washington, D.C., remembers arriving at Wake Forest as a first-year student from Florida when Black student enrollment was lower and “looking around and not seeing anybody like me at all.” On the Quad, though, he spied Karen, “and I was like, ‘Hey, that’s my person!’” They ate meals in the Pit, studied together, tailgated and danced to D.C.’s Go-go funk music. Whether it was about promoting disinvestment in apartheid-era South Africa or working to establish Wake Forest’s first Black sorority or advancing race relations on campus, he says Karen “was the leader of most of those movements.”

Wake Forest’s was “a tough climate while we were there,” Stanley says, but it allowed Karen, a politics major, “to really expand her thinking about what justice looked like.” To Karen, “it didn’t matter whether (people) were Black, white or whatever,” says her mother. “(But) she went to Wake Forest, and everything was black and white. She said she thinks she lived in a shade of gray until she went to Wake Forest, but she wouldn’t have traded it for anything.”

Karen, 53, professes a love of Wake Forest despite the challenges on campus for Black students in the 1980s. “It helped me get active and even more civically engaged around issues of equity, around inclusion, just all the things that I’ve now worked on throughout my career. I really found my voice at Wake Forest.”

"In some ways she is this weaver of justice. She knows how to weave or sew this quilt, and she puts together people, practices and power.”

– RAFAEL LOPEZ, former senior White House policy adviser

When it came time to study abroad, Stanley chose Casa Artom in Venice. Karen chose Liberia. Her parents vehemently opposed the idea. Angelou wrote them on Karen’s behalf and sent along an autographed copy of her latest book. Case closed. Karen, a junior, was going to Africa.

A man passed Karen as she disembarked from the plane that landed near Liberia’s capital, Monrovia. “Welcome home, sister,” he said. From those words and experiences during her semester abroad, she found “a sense of wholeness, a sense of belonging” and “my power as a Black woman.”

Stanley remembers how she came back “on a whole different level. Her awareness, I think, became much more global and connected to a larger framework and a larger movement.”

She made her way, as always during her college days, to Caswell County with this larger view of the world, reminded of the work to be done close to home. As she drove to see Mama Bea, she passed handmade KKK signs pointing to the woods, she says. She figured a Klan meeting was underway. There was no sense in stopping to find out.

Karen’s parents opposed their daughter’s wish to study abroad in Liberia until they received a letter and book from the late Maya Angelou, a Wake Forest professor who changed Karen’s life.

Karen’s trajectory after Wake Forest could fill volumes. It started with a law degree at the University of California Berkeley School of Law and a job at the esteemed Alston & Bird law firm in Atlanta working on antitrust litigation. Working pro bono assignments prompted her to abandon the high salary and international law firm prestige to follow her heart and work on behalf of children and families — all before she was 30.

She helped create and run the Court Appointed Special Advocates program (CASA) to help foster children with permanent placement in Fulton County, Georgia. Barely 30, she was appointed to the bench in Fulton County as a juvenile court judge by Glenda Hatchett, then-chief presiding judge of the juvenile court and now in private practice. She continually relies on Karen’s counsel.

“First of all, she is brilliant,” Hatchett says. “I’ve seen her in tough situations, and she is just unflappable. She has this strong moral compass. She is going to do what is right even when it’s not popular.”

Her jobs in the past decades were never easy — or, as she would say, linear. Among her other roles, she was appointed as a federal monitor overseeing reform in Georgia’s children and family services department. She led a special initiative in Alabama for an alternative to detention for juveniles. She developed training and research at the University of Georgia’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government to educate and influence policymakers about children and family issues. She taught at Emory University and the University of Alabama.

Her jobs in the past decades were never easy — or, as she would say, linear. Among her other roles, she was appointed as a federal monitor overseeing reform in Georgia’s children and family services department. She led a special initiative in Alabama for an alternative to detention for juveniles. She developed training and research at the University of Georgia’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government to educate and influence policymakers about children and family issues. She taught at Emory University and the University of Alabama.

At the University of Georgia, she met and eventually supervised Allison McWilliams (’95), now assistant vice president, mentoring and alumni personal & career development at Wake Forest. “She’s this teeny, tiny person who walks into a room, and you would swear she’s 6 feet tall,” McWilliams says of her mentor for life. “She’s probably one of those people I learned the most from about lifting other women up.”

McWilliams will never forget how Karen was a reference for her first Wake Forest job. Before the call was over, the topic changed from McWilliams to an invitation to Karen for a speaking engagement. “With a 10-minute reference call, she just blows you away,” McWilliams says.

Rafael López, a former senior policy adviser in the Obama White House, has known her since the mid-2000s on their way to becoming national fellows with the Annie E. Casey Foundation. At López’s invitation, Karen took foster children to the White House to encourage and motivate them.

“You can see children and families who are nothing but broken and problems” in the child welfare system, he says, “or you can see children, youth and families who have possibility and hope and strength and beauty. I think Karen is one of the people who sees that everyone has strength and possibility and beauty already in them.” He adds, “She embodies justice. She embodies empathy. She embodies ethics and morality.” Her concern for children, he says, is genuine.

Some of that empathy flows from her experiences on the bench and in tackling policy questions, some from her personal life. She and her first husband adopted a 15-month-old Black foster child born to a troubled mother of 13 children. Karen had a biological son later, and he is in high school. She has two stepsons with her current husband, Art Dunning, the retired president of Albany State University, a historically Black institution in Georgia.

Despite having been brought up in an upper-middle-class home, her adopted son, at 20, got into serious legal trouble that Karen says has been “heart-wrenching.” Karen and her son have minimal contact. “I pray for him,” she says. “I just try to keep a lifeline open.”

Her private pain cannot help but fuel her public life. She reminded her audience of Maya Angelou’s lesson and Terence’s quote about nothing human being alien to her — whether someone’s circumstances are bad or good —when she spoke at an NAACP awards banquet in Jackson County, Florida, in 2019. “When you see injustice, even when it does not impact you personally, remember ‘I am human’ and take action,” she told the audience.

“When you see injustice, even when it does not impact you personally, remember ‘I am human’ and take action.”

– KAREN BAYNES-DUNNING

She takes action even when others would run the other way. She made national headlines when the board at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) in Montgomery, Alabama, asked her to relinquish the board seat she had held since late 2017 and take over as interim president and CEO of an organization in an uproar. Since its founding in 1971, the nonprofit has been known for tracking and exposing activities of hate groups and for its civil rights cases, including multimillion-dollar verdicts against Klan groups in the 1980s. In the past it had been criticized for its fundraising tactics and financial practices.

In March 2019, a new level of turmoil engulfed the SPLC after national news broke — its co-founder Morris Dees had been fired for unspecified misconduct and its president had resigned. Employees alleged mistreatment of all stripes. At the board’s request, Karen stepped into this fire the following month.

Bryan Fair, the Thomas E. Skinner Professor of Law at the University of Alabama School of Law, is the SPLC’s board chair and knew Karen and Art Dunning from their days in Tuscaloosa. Karen “had almost no significant involvement before the turmoil nearly brought the organization to a halt,” he says. But she had to deal with the issues that had been festering: “systemic structural racism and feeling that the organization wasn’t living its beliefs and values.”

Karen’s task was formidable. She worked extraordinarily long hours, he says, and listened to everyone from the line staff up to board members to assess the organization’s infrastructure and management. The conversations were at times contentious. “I don’t think anyone could have done the job as well as Karen did,” he says. “It required all of her talent. And I think one of her talents is this ability to listen with empathy and to operate with a kind of grace that I think few people have.” Her leadership, he says, was “vital to rebuilding the sense of community within the organization.”

Karen found “a trauma-filled work environment” that had “a conflation of Me-Too and gender-related issues” with issues of race and class, she says. The organization had doubled in revenue and staff after the 2016 presidential election and had not established the infrastructure and human resources policies to support that growth, she says. She had the difficult job of leading conversations around “any vestiges of white supremacy culture that may exist” and took heat for problems created before her time.

In the end, a new director was named in spring 2020, as planned. Karen says, “I think we went a long way in starting to create those systems to support the staff and the work.” She remains optimistic about the organization’s mission of confronting racism, teaching tolerance and supporting voting rights. “There are young, passionate advocates that will change the world,” she says.

Today, Karen makes her home in Greenville, South Carolina, the place she and her husband selected after Art Dunning retired in 2018 from his university presidency. Karen is a consultant and executive coach, working on Zoom like so many of us in the time of COVID-19. But it took only a few months after her tenure ended at SPLC for Greenville officials to come knocking.

In July the city council appointed Karen to an ad hoc citizen advisory panel on public safety to assess policies, training and use of force in the police department in the wake of George Floyd’s killing in police custody in Minneapolis. By summer’s end, Greenville leaders from the chamber of commerce, the Urban League and the United Way had persuaded her to be a member of their newly formed Greenville Racial Equity and Economic Mobility Commission. The group’s charge is to develop strategies “to implement significant change in the areas of racial inequities, social justice, and other key gaps identified as focus areas of the Black community.”

If the work of confronting and dismantling institutional racism tires Karen or burdens her soul, she does not speak of it publicly. Her strength, her friends say, is rooted in faith and family. Peace she can find in Caswell County, for one place. If she chooses, she can sit under an ancient sycamore tree at her parents’ house and contemplate the miraculous journey of her family. This property is part of the 400 acres where Mama Bea and Daddy Waymond did back-breaking labor for the Harrelson sisters. Back then, the two sisters thought nothing of giving the Tottens a used frying pan for Christmas. Mama Bea spent night and day caring for the surviving sister, who was ill, leaving her own family at times to fend for themselves. Who would have ever imagined that the sister would call Daddy Waymond to her deathbed with news to floor him and surely the whole of Caswell County?

The Baynes Family Farm hosts Camp Phoenix for a week every summer for children who are homeless.

She announced she was leaving him all the acreage; the white, wooden, two-story farmhouse where she lived (and now was dying); the antiques and enough cash stashed in a hiding place to pay the estate taxes. It was 1969, and with that bequest the fortunes for the older generation changed utterly. They lived in the house until it burned five years later. With the help of Percy and Dorothy, a brick house was built in its place. The Tottens subdivided the property, but there are 178 acres left for Dorothy and Percy with the brick house, and it represents home, abundance and family.

On Karen’s father’s side, the Baynes property with its modern log house functioning as a retreat on what Percy calls “my very own launch site” brings Karen and her family a sense of purpose and a gift for the next generation. Every summer, except during COVID, the family hosts Camp Phoenix, a one-week adventure for children who are homeless. Here, they can run and play and be free, just as Karen and her siblings did. Karen leads the annual tie-dye session. The children make “special pillowcases” that are signed by fellow campers and carry memories from Camp Phoenix, “so that you can always know where you can lay your head.”

These family lands are an anchor for Karen, a place where she feels her ancestors’ spirits abiding. “There’s something special about our family’s ability to keep this land because a lot of African Americans were not able to,” she says. They remind her of what Maya Angelou used to say to her: “Surviving is important, but thriving is elegant.”

Though the work remains to fashion a more perfect union, the land of Caswell County, with all of its stories and all of its mysteries of justice, will keep calling Karen home, no doubt to thrive.

The modern Baynes Family Farm retreat center on 90 acres in Caswell County. Photos by Steve Baynes

“When you look at her life, it’s about richness and about wholeness and about diverse and broad-based experiences.”