Robert J. Carroll ('74) is sworn in on Oct. 14, 2020, as Acting Morris County Prosecutor with his daughter, Kimberly Carroll, holding the Bible and his wife, Roseann, in the background. Former New Jersey Supreme Court Chief Justice James Zazzali conducts the swearing-in. Top, Carroll and Richard "The Iceman" Kuklinski, a notorious mob hitman caught by a task force headed by Carroll.

Bob Carroll (’74) points to 25 years helping Native American tribes as the most rewarding of his legal career, but his native New Jersey voice animates a notch as he recalls his years investigating the likes of the murderous Richard “The Iceman” Kuklinski and other mobsters.

Carroll sees long-term impact from his work for the tribes, giving them an economic engine with gaming and new governing structures to help restore their cultures. Last year, he took on a new phase as a county prosecutor in Morris County, New Jersey, hoping to improve racial and social justice and community relations with law enforcement. More on those later.

But first he shares the details of what he calls the “predator hunter” first phase of his career, outwitting organized crime — brutal killers, drug traffickers, environmental polluters, porn and prostitution brokers and video poker kings peddling gambling addictions. His cases have inspired more than a dozen TV specials, films and books.

“I get excited when I start talking about this stuff,” he says. “Most of the prosecutors I know may have one or two of these things, but I just seemed to be in the right place at the right time.”

The list of his headline-worthy prosecutions is long. He led the New Jersey Organized Crime and Racketeering Task Force in the 1980s and was a prosecutor focused on mobs and corruption until the early 1990s. He is quick to note that he didn’t do it alone. “To say that these were my babies is a gross overstatement. There were so many people that contributed to these things.”

At 6-foot-3, Carroll had football skills that generated interest from other universities, but he says none was “as inviting or welcoming as Wake Forest.”

Getting to Wake Forest

Robert J. Carroll, nicknamed “Red,” played scholarship football as an offensive lineman at Wake Forest, the first in his family to go to college. He was followed at Wake Forest by a sister, Denise Carroll (JD ’87); a brother, James J. Carroll III (’78, P ’04, ’07); a nephew, James J. Carroll IV (’04); and a niece, Amanda Carroll Flores (’07) — all attorneys now — and sister-in-law Candy Love Carroll (’77, P ’04, ’07).

At 6-foot-3, Carroll had football skills that generated interest from other universities, but he says none was “as inviting or welcoming as Wake Forest.” Coach Cal Stoll “told us we were going to win a championship. We did.” The team won the 1970 ACC title.

Carroll had learned the values of hard work, education and looking out for each other from his father, a World War II veteran who built submarines, then worked construction. His father led union organizing after seeing former soldiers mistreated on the job. Carroll says he had never lived with Black students and with Southerners, and Wake Forest taught him another value: diversity.

He didn’t aspire to professional football, seeing more career potential through academics. He found his calling during a six-week “January term” independent study at home. His father urged him to sit in on trials to consider law, and a prosecutor took him under his wing. Carroll showed up each day “with the same sport jacket and the same crappy little tie on because I wanted to look like I belonged there.” He wrote a report on lawyers’ techniques. He was hooked.

After graduating, he married his wife, Roseann, and worked days as a police officer while attending law school at night at Seton Hall University. Officers in an organized crime and corruption task force mentored him and taught him an important — and effective — lesson: treat everybody with respect, even criminals, and you’ll get respect. He learned how to spot corruption-proof colleagues. A stint writing appellate briefs taught him how to make a case stick.

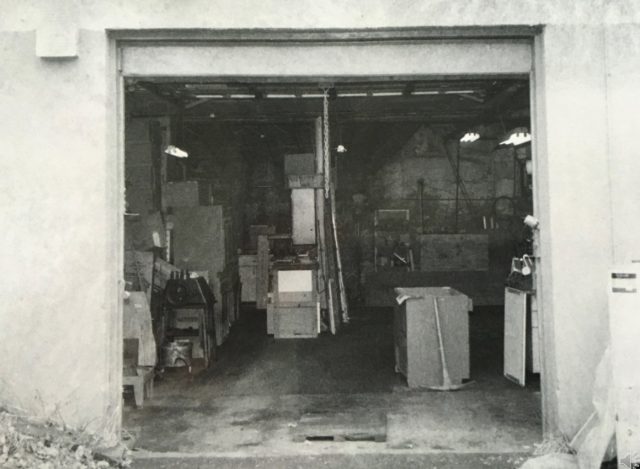

The Iceman had a garage in North Bergen, New Jersey, where he froze and dismembered some of his victims' bodies.

The Iceman: “You guys, you’re not stupid.”

Richard “The Iceman” Kuklinski in the driveway at his home in Dumont, New Jersey, as investigators try to interview him.

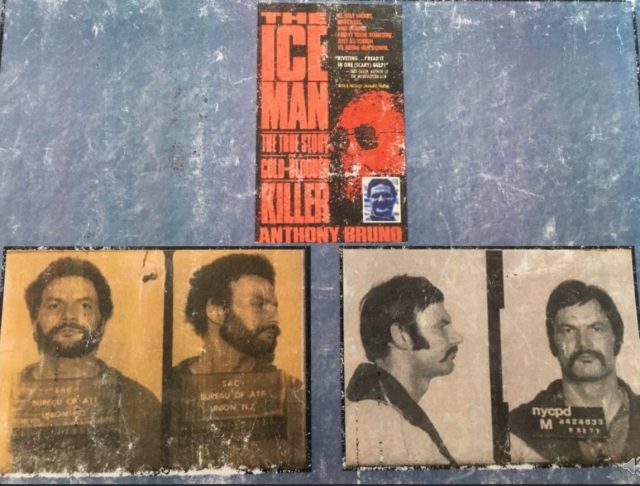

Carroll’s most famous mob case was Kuklinski, a hitman in New Jersey who solved every problem with a stabbing, bludgeoning, shooting, garroting or poisoning. He was convicted in 1988 and died in prison in 2006. A movie, a book, three HBO specials, podcasts and 10 TV or cable segments and counting have chronicled The Iceman’s blood-thirsty life. Carroll says he is surprised at how producers “keep repackaging these things,” seeing new audiences for the story.

One of Kuklinski’s many crime models was “businessman murders,” furnishing cyanide and instructions on how to poison someone. He set up appointments but played hard to get, standing up buyers until they got desperate enough to show up alone with cash. Then he robbed and killed them. The Iceman often kept bodies in his garage freezer in North Bergen, New Jersey to confuse time-of-death forensics (hence, his nickname) and give him time to dismember and bury them in 55-gallon drums.

In the early 1980s, he decided to kill a gang of four low-level confederates who could rat him out. He killed two, one with cyanide in baked beans, the other by strangling him when he didn’t die fast enough from cyanide-laced ketchup on a hamburger. The wife of one dead confederate was having an affair with the third, and Kuklinski needed more cyanide to kill the third rat and the widow because he had killed his chemist source. That set the stage for Dominick Polifrone, an agent of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms who was working undercover in an 18-month joint operation with Carroll’s task force.

Dominick Polifrone, an undercover agent for the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, set up the dangerous sting of The Iceman with Carroll's task force in a joint operation. This is Polifrone's "legend," or undercover persona, and a book about the case by Anthony Bruno.

The sting operation drew from Kuklinski’s own hard-to-get playbook and turned it back onto him, with Polifrone moving slowly to supply the cyanide. Kuklinski, knowing he would eventually kill Polifrone, dished freely to him about two murders, but the team wanted to pin more on him. Polifrone set up a fake drug deal. He and Kuklinski would steal the buyer’s $80,000 and murder him.

At the meet, Polifrone delivered fake cyanide to Kuklinski, who said he needed to go home briefly. He was arrested heading back with three egg salad sandwiches, all laced with the fake poison he intended for the buyer, Polifrone and yet another confederate delivering a van to haul off bodies.

Kuklinski had five, possibly six murders in his head all at once, Carroll says. “This is a master killer. It’s the logistics of that type of thinking of a killer that to me is fascinating,” he says.

Kuklinski recognized that he fell prey to his own strategy of keeping the victim on the hook, telling investigators later, “You guys, you’re not stupid.”

Carroll investigated the explosion and 15-hour fire at Chemical Control Corporation in Elizabeth City, New Jersey, in a mob-affiliated overcrowded storage facility. The 1980 explosion added to momentum for federal Superfund toxic cleanup legislation.

Crime families

A 1980s video poker machine

Carroll and his team indicted dozens of members of the Frank Lucchese crime family of La Cosa Nostra in 1991 and achieved what the FBI couldn’t do in previous trials: convict the top leaders. “I had all the heads of the families,” says Carroll, who prosecuted the case in court himself. A defendant later admitted the family bribed jurors in the FBI’s cases.

Carroll was part of the trial team that won a prison sentence for Frank Lucas, whose flamboyant drug life in the 1970s and ’80s and his “Country Boys” gang inspired the “American Gangster” movie with Denzel Washington and Russell Crowe.

Immersing himself in the gory world of organized crime might not seem like a Pro Humanitate space, but Carroll took very bad guys off the streets. The task force tackled pornography, prostitution and video poker machines. Mob affiliates were mass-producing the machines in New Jersey and rigging them to allow illegal cash payouts instead of game credits. Addictions soared.

“States would tell us their kids, 13, 14 years old, were skipping school to play these games,” says Carroll. “We were trying to stop an entire corrupt industry from getting its claws into them.”

Carroll investigated major environmental crimes, including a chemical explosion and 15-hour fire in 1980 at a mob-affiliated, overcrowded chemical storage plant in New Jersey. The poisonous fumes threatened to shut down Staten Island. The case fed federal momentum for “Superfund” toxic waste cleanups, Carroll says.

Carroll achieved daunting convictions before cell phones and DNA tests. Former New Jersey Gov. Richard Codey, a state senator then and now, says Carroll “did an incredible job, winning convictions of some of the state’s most dangerous and notorious criminals. He knew the lingo. He could talk to anyone of any background.”

Carroll employed his early lesson of respect, leading criminals to inform or confess or blunting their vengeful impulses.

Carroll recalls running into a Lucchese crime family member out on bail on murder and racketeering charges. They met in the tool aisle in a Home Depot.

“I’m saying to myself, ‘Is this guy going to flip out and grab a hammer? … He says, ‘Hey, Bob, how you doin’?’ I say, ‘OK, how are you?’ He says, ‘Ah, OK now, but I gotta go back in (to prison), thanks to you.’ I said, ‘What can I say? It’s a job.’ He goes, ‘Yeah, I know. I know.’ That was it.”

Carroll faced much greater intimidation: one of the task force offices was firebombed, and the Gambino family targeted Carroll’s own office in a thwarted arson plot. The task force took steps to ensure the safety of their homes and families.

“It’s something you just put in the back of your mind,” Carroll says. “I can’t think of any other way of explaining.”

“He’s unassuming, patient, tolerant and a good man. I always felt a little smarter after being in a room with him.

Switching gears

After years of dealing with violent criminals, Carroll was getting a little tired — of driving two hours each way from his home to the state capital.

“I said to my wife that I’ll take a shot at private practice for a few years, maybe make some more money, buy a home.”

He joined a law firm in 1991, helping Native American tribes set up gaming under federal legislation approved in 1983.

“Tribes were desperate to hire people and keep the mob out,” Carroll says, and they knew former prosecutors weren’t tied to organized crime. “They didn’t have any confidence that they wouldn’t be taken advantage of because, let’s face it, Native Americans have been taken advantage of since the very beginning.”

Carroll helped the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation create Foxwoods Resort Casino in Connecticut in 1993 and assisted tribes and state governments around the country. Gaming created thousands of jobs and revenue for tackling harsh poverty. “We developed entire systems of tribal codes, ordinances, regulatory systems, police departments, court systems … in a fashion that enabled the Indian culture to shine through.”

Carroll helped the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation create Foxwoods Resort Casino in Connecticut in 1993 and assisted tribes and state governments around the country. Gaming created thousands of jobs and revenue for tackling harsh poverty. “We developed entire systems of tribal codes, ordinances, regulatory systems, police departments, court systems … in a fashion that enabled the Indian culture to shine through.”

Carroll helped set up peacekeeper courts for minor juvenile offenses. Three community elders “scold them, teach them and guide them that there’s more to their life.”

Carroll believes the movement helped in saving the culture, albeit in a different form, and allowed many young leaders to emerge. “You might put a mobster in prison for 15 or 20 years, but this had a generational impact,” he says. “The role I played, whatever small amount I had, I’m very proud of.”

Lt. Col. Kenny Van Buren, who heads investigations for the Louisiana State Police, says his state and its tribes wouldn’t have gaming without Carroll’s efforts to balance the needs of both. “He’s unassuming, patient, tolerant and a good man,” Van Buren says. “I always felt a little smarter after being in a room with him.”

Law enforcement cannot exist without community support. You just can’t. I think that’s an area where I can help them.

Coming out of retirement

Carroll left private practice to deal with health issues and tried retirement. (He’s 69.) It was comfortable, but he was restless. He rejoined state government for two years as director of the Law Department of the New Jersey Turnpike Authority. Last fall, he accepted the governor’s appointment as Acting Morris County Prosecutor, pending state Senate approval of his five-year appointment.

Carroll was dismayed and hurt by law enforcement’s tattered reputation amid national tensions over police tactics and racial strife. He says the system must evolve to be fair and effective.

“Law enforcement cannot exist without community support. You just can’t. I think that’s an area where I can help them,” says Carroll.

Besides starting as a police officer, he investigated the officer whose shooting of a Black teenager in 1991 prompted the infamous riots in Teaneck, New Jersey. Carroll absorbed the vision of then-state Attorney General Robert Del Tufo that police too often can’t build trust without independent investigations of abuse. “I’ve been through that crucible and back,” Carroll says. Both police and victims deserve justice, he says.

He wants to rebuild relationships between law enforcement and those they serve. He has met with Black Lives Matter leaders, faith leaders, the NAACP and the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement to develop effective communication.

“This is a historical time in our country, and I’m hoping to make a difference,” he says.