Some of the grandest estates in Winston-Salem are maintained by Wake Forest, including Reynolda House (top), the President's Home and Graylyn.

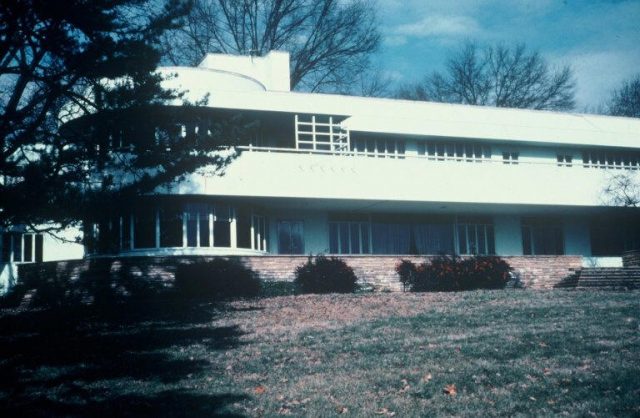

W hen I was recruited in 1979 to Wake Forest from Boston University, where I headed the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation, many of my colleagues noted that Winston-Salem was “cool.” To them, the town had two notable buildings: the shell-shaped Shell Station constructed by Quality Oil Company to promote its Shell Oil products, and Merry Acres, an International Style residence locally known as “the Ship,” designed by Luther Lashmit for R.J. Reynolds’ heir, Dick Jr.; his first wife, Blitz; and their four boys.

By the time I arrived, the Shell Station had seen better days. (The sole survivor of eight original stations, it was later restored by Preservation North Carolina and is still extant on Peachtree and Sprague streets.) But the Ship, a modernist mansion that had been donated by Reynolds heirs to Wake Forest, was gone. Remnants of stone entrance walls on Buena Vista Road were the lone marker of the estate’s existence.

Merry Acres, aka “The Ship.”

Once here, I discovered that locals had other favorites — the Reynolda and Graylyn estates on Wake Forest’s front doorstep, the Moravian architecture of Old Salem and the R.J. Reynolds Office Building, whose Art Deco design (as everyone in town seemed to know) was by the architects who later designed New York City’s Empire State Building.

In the next 32 years of teaching art and architectural history at Wake Forest and 16 years as department chair, my interaction with the local community was limited. I drove from my home in the West End up Reynolda Road to campus, with detours to the Cloverdale Harris Teeter, the Thruway Shopping Center and the Central YMCA. My research was focused on statewide and national topics, such as the North Carolina Women’s History Project and the evolution of ski resorts in North America.

In 1981, I curated “Reynolda, An American Country House,” the first exhibition to explore the social history of the country estate designed by Philadelphia architect Charles Barton Keen for tobacco magnate Richard J. Reynolds and his wife, Katharine. Through the years, I had taught seminars on country house architecture exploring local estates and landscapes.

I was delighted to realize just how significant a role the University played in preserving Winston-Salem’s distinctive architectural legacy.

Ten years ago I retired and soon afterward was asked to write a book on Winston-Salem’s great houses. (“Great Houses and Their Stories: Winston-Salem’s Era of Success 1912-1940” is expected to be available in late fall 2021.) A local topic seemed great for a retirement project. My husband, Jackson Smith, is a superb architectural photographer, and I thought he might also find this hometown project interesting.

I had a lot to learn about Winston-Salem. The early 20th-century “Camel City” was an aspirational town, and accounts of its economic, civic, cultural, religious, racial and social life are recorded in copious detail in local newspapers. Newspapers.com and ancestry.com made accessing the past easier, more fun and definitely more informative. The book project gave me the opportunity to walk up and down tree-shaded streets researching various houses and estates and definitely increased my appreciation for the architecture and landscapes in my adopted hometown. In the eight years I worked on the book, I made new friends and acquaintances, some of whom remembered the houses as children or were new homeowners excited to be part of history.

The extraordinary success of Winston-Salem’s tobacco and textile industries established a civic landscape that, even today, is largely intact. Winston-Salem was hardly unique in having a set of great houses designed and built for rich folks, but for the most part, the country estates that lie on the town’s edges and the great suburban houses that line its elite residential neighborhoods are still there.

Author Margaret “Peggy” Smith

When my family moved to town, Winston-Salem at times smelled like tobacco. The pervasive smell extended from warehouses and factories out to the Wake Forest campus. That pungent aroma lingers no more, but the legacy of Winston-Salem’s tobacco and textile heyday survives in our residential architecture, though the new homeowners are likely to be in finance, technology, law and medicine.

The book’s objective is to highlight this important facet of Winston-Salem’s rich local history, with its roots in tobacco and textiles, and to establish a case for the value of preserving its exceptional architecture, which looks venerable but is surprisingly fragile and could be lost, simply by an individual homeowner deciding to demolish his or her property.

Located in the midst of Winston-Salem’s “Emerald Necklace” of country estates, the University assumed stewardship in the 1970s of three major estates, Reynolda, Graylyn and Merry Acres, in what must have been a triple whammy for the nonprofit University whose mission was education, not historic preservation. In the 1980s it acquired DeWitt and Ralph Hanes’ grand house (now the President’s Home), and, most recently, the Davis family’s Sunnynoll for an educational institute. It has also stepped up in the adaptive reuse of the tobacco factories downtown in Innovation Quarter.

Restoring and maintaining historic estates is not inexpensive, and I was delighted to realize just how significant a role the University has played in preserving Winston-Salem’s distinctive architectural legacy.

Harold W. Tribble Professor Emerita Margaret Supplee Smith was chair of the Department of Art, where she taught art and architectural history. She helped establish the Women’s Studies Program and co-authored the award-winning “North Carolina Women: Making History” (UNC Press, 1999). She wrote “American Ski: Architecture, Experience and Style (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013).

TOP: A view from the balcony overlooking the Reynolda House reception hall. BOTTOM LEFT: The gardens at the President’s Home. RIGHT: Graylyn features a distinctive stone facade. (Ken Bennett photos)

Great Estates

A closer look at three historic treasures owned and maintained by Wake Forest.

Photos by Jackson Smith

REYNOLDA HOUSE<br /> <br /> Built in 1917, Reynolda House was the center of the 1,067-acre Reynolds country estate that initiated the westward suburban growth of Winston-Salem. Today it houses an exemplary collection of American art and is complemented by Reynolda Gardens and Reynolda Village. <br />

GRAYLYN ESTATE<br /> <br /> Built in the Norman Revival style, the Graylyn manor house (1928-32) was designed by famed architect Luther Lashmit for the 87-acre country estate of Nathalie and Bowman Gray, the first non-family president of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco. The complex today is the Graylyn International Conference Center. <br />

THE PRESIDENT'S HOME<br /> <br /> The elegant country estate of DeWitt and Ralph Hanes was designed in 1929 by New York architect Julian Peabody with gardens by noted landscape designer Ellen Shipman. Today the stately complex in Chatham Farm is the residence for Wake Forest's president. <br />