Anthony “Wayland” Johnson (’61) is rightly proud of what he and nine other Wake Forest students did in February 1960. At the time, he didn’t think it was that big a deal, although in reality it was historic when white students from Wake Forest sat down at a whites-only lunch counter with Black students from what’s now Winston-Salem State University.

He doesn’t want the significance of the Winston-Salem sit-in protests, which led to the desegregation of the city’s restaurants and lunch counters, to be forgotten. “In my lifetime, I treasure what we did that day as the most important thing I ever did,” Johnson wrote in a letter to Wake Forest Magazine this summer. “We never regarded ourselves as heroes. We simply believed the status quo was wrong.”

A photograph in the summer 2021 Wake Forest Magazine prompted Johnson’s letter. The photograph shows then-Wake Forest President Nathan O. Hatch (L.H.D. ’21) and WSSU Chancellor Elwood L. Robinson at a commemoration in 2020 marking the 60th anniversary of the sit-in.

Johnson was afraid that no one today cared about something that happened six decades ago until he saw the photograph. “I had no idea that any impression was made or memory remained of that,” he wrote.

When I received Johnson’s letter, I called him to hear the rest of his story. He was pleased to hear that a historical marker in downtown Winston-Salem, near the site of the old F.W. Woolworth’s, commemorates the sit-in. He asked me to read him the text on the marker.

Winston-Salem State University Chancellor Elwood L. Robinson and Wake Forest President Nathan O. Hatch (L.H.D. ’21) at a commemoration marking the 60th anniversary of the Winston-Salem sit-in. Victor Johnson, one of the original sit-in participants, is at right.<br />

The marker gives the bare-bones version of the sit-in. Here’s the longer version.

The sit-in protests in Winston-Salem and across the South began after four Black students from North Carolina A&T State University sat down at the whites-only lunch counter at the Woolworth’s (now the International Civil Rights Center & Museum) in Greensboro on Feb. 1, 1960. A week later, a Black Winston-Salem man, Carl Matthews, began a sit-in at the lunch counter at the Winston-Salem Woolworth’s. He was soon joined by students from WSSU (it was called Winston-Salem Teachers College back then).

Ten Wake Forest students joined them on Feb. 23: Johnson, Don F. Bailey (’61), Joe Chandler (’61, JD ’67), Linda G. Cohen (’60), Margaret Ann Dutton Stevens (’60), Linda Guy Alford (’61), Bill Stevens (’60), Paul Watson (’61), George Williamson (’61, P ’94) and Jerry Wilson (’62, JD ’64).

Shortly after entering Woolworth’s, Matthews, the Wake Forest students and 11 Winston-Salem State students were arrested and charged with trespassing. They were found guilty a week later. But the sit-in led to the desegregation of the city’s restaurants and lunch counters three months later and was the first successful sit-in protest in North Carolina.

It was significant that white students joined Black students and were arrested alongside them, wrote Wake Forest religion Professor G. McLeod “Mac” Bryan (’41, MA ’44, P ’71, ’72, ’75, ’82 ) in a history of the sit-in. Bryan was a mentor to many of the students and an outspoken voice against segregation.

(Wake Forest Professors Mary Dalton (’83) and Susan Faust made a 2001 documentary on the sit-in, “I’m Not My Brother’s Keeper: Leadership and Civil Rights in Winston-Salem.” Williamson has spoken frequently about the sit-in, including in the summer 2009 Wake Forest Magazine. Bill Stevens was interviewed by Sarah Yaramishyn Nolin (’00) in 1999.)

Johnson still has vivid memories of the sit-in. When I reached him by phone at his home in Gladstone, Virginia, he was just back from a fly-fishing trip to North Carolina’s Outer Banks and was soon to depart for Alaska. He’s about as delightful an 82-year-old as you’ll ever meet. He loves opera, fly fishing, moose hunting and traveling the world (even to Antarctica, he told me). He lives in a log house that he and his brother built on a cliff above the James River in Gladstone, about 20 miles north of Appomattox.

Johnson grew up in segregated North Carolina, the oldest of four children. His father, William Iver Johnson (1929), was a Baptist minister. He worked hard to get to Wake Forest, plowing the fields with a mule and raising tobacco and corn on his great-aunts’ farm in Haw River to earn money for tuition.

When he enrolled in 1957, the biggest issue on campus wasn’t integration but the ban against dancing, put in place by the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina. He was one of hundreds of students who walked out of the compulsory chapel program in Wait Chapel on Nov. 20 that year to protest the dance ban. He was on the wrestling team, sang in the choir and was a drummer in the marching band that appeared in the 1957 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City, where he attended his first opera.

He hadn’t planned to make history when a Sigma Pi fraternity buddy asked him to join the students going downtown to protest the segregated lunch counters. Some of the students had talked about the sit-in movement with Mac Bryan. Some had talked with WSSU students the night before.

Why did he decide to go downtown?, I asked him. “I’ve always been outspoken about what I believed was right and wrong,” he said simply, adding that he wasn’t an “activist.”

“I didn’t have the prejudice that my parents had; I don’t know why not. I just thought a lot of things were wrong, like (Blacks) riding in the back of the bus.”

Wayland Johnson's senior picture, from the 1961 Howler

He tells his story of that day matter-of-factly. “I vividly remember going into Woolworth’s. We walked in and sat at the counter and ordered lunch. When it came, we gave it to the people from Winston-Salem State, and they ate it. I didn’t think it was any big deal … until the police came in.

“I never was afraid, but I think about the mob outside, and I should have been afraid,” he said. “I don’t want to be too dramatic, but I really believe the police saved our lives. There was a really angry mob outside, seemed like hundreds of people, yelling and cursing.”

The students were arrested, fingerprinted, photographed and placed in segregated “bullpens.” Johnson called English professor Edwin G. Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93), then Dean of the College and later Provost, for help. The students’ $100 bond was paid by Chaplain L.H. Hollingsworth (’43, D.D. ’59, P ’61), religion professor Dan Via (P ’83) and Mark Reece (’49, P ’77, ’81, ’85), then director of student affairs and later Dean of Men. “He (Wilson) got us an attorney and he got us out that night, so we didn’t spend the night in the pokey,” Johnson said.

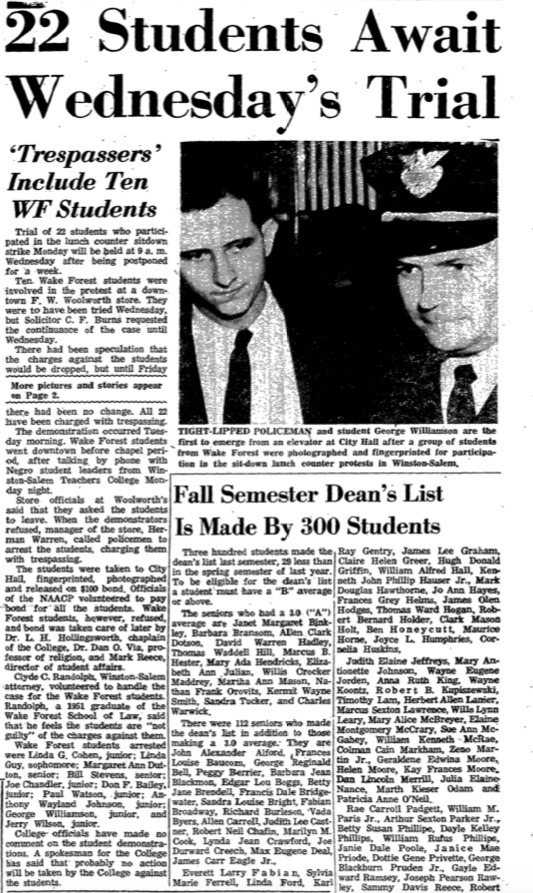

Their trial was held just a week later in Municipal Court. School of Law alumnus Clyde C. Randolph (JD ’51) represented the students. The Old Gold & Black reported on the students’ arrest in its Feb. 29, 1960, issue and the trial in its March 7, 1960, issue.

The Old Gold & Black from Feb. 29, 1960, shows a grim George Williamson ('60, P '94) being led off to jail.

As the sit-ins had spread across the city, some downtown stores had closed their lunch counters. Woolworth’s had posted a sign that its lunch counter was for employees and their guests only. The Woolworth’s manager testified

that Dutton “forced her way” into the lunch counter area. Dutton disputed that, saying that she had asked an employee, “May we eat here?” The sign was “only a cover-up for segregation,” she said in court. Dutton testified that she ordered a cup of coffee, which she gave to a WSSU student, and a piece of pie.

Dutton and Johnson were the only Wake Forest students called to testify. Johnson still bristles at some of the questions they were asked. The prosecutor questioned Dutton about a trip that she and another student had taken to Vienna the previous summer, suggesting that she had participated in a Communist-sponsored Youth Festival, which Dutton denied. “They were accusing us of being Communists,” Johnson said. “They dragged out everything (to throw) at these young whippersnappers.”

Johnson was asked why he had moved so many times when he was growing up. Johnson’s family had moved frequently because his father was a minister, but he didn’t see what that had to do with anything. “He got to hounding me, and I sort of blurted out, ‘He (his father) moves whenever God tells him to move,’” he said.

The Woolworth’s manager also testified that the students had been asked to leave the store. Dutton and Johnson both testified that no one asked them to leave until the police arrived.

Black protesters sit down at the Woolworth's lunch counter on Feb. 9, 1960. (Photo: Winston-Salem Journal)

The trial was over quickly. Judge Leroy Sams found Dutton and a WSSU student guilty of trespassing. Since the students all faced the same charge, he found all of them guilty. He suspended judgment for 12 months, but never issued a final judgment. “I wasn’t guilty of anything except giving food away,” Johnson told me.

The Wake Forest students didn’t face any punishment on campus, but reaction among other students, alumni, trustees and parents was overwhelmingly against them, Bryan wrote after the sit-in. President Harold W. Tribble (LL.D. ’48, P ’55) summoned the students to his office and told them they should concentrate on their classes and be good students, Bryan wrote.

North Carolina Gov. Luther Hodges urged Tribble to “restrain” the students. Some local residents wrote letters to the students condemning their actions, the OG&B reported. “All of you are a disgrace to Wake Forest College, all of you should be expelled,” read one of the nicer letters. “All of you Beatniks have really made a nice name for yourselves that will be hard to live down.”

The Old Gold & Black, the student legislature and alumnus Harold T.P. Hayes (’48, L.H.D. ’89, P ’79, ’91), editor of Esquire magazine, supported the students. Some 60 faculty members signed a petition calling for lunch counters to be integrated.

As the sit-ins continued into the spring, Wake Forest sociology Professor Clarence Patrick (’31, P ’69) was appointed to a “Goodwill Committee” to study what the Winston-Salem mayor called “the lunch-counter problem.” The committee eventually recommended that lunch counters be desegregated, and local merchants agreed.

White patrons wave Confederate flags at Blacks sitting at the Woolworth's lunch counter on Feb. 9, 1960. (Photo: Winston-Salem Journal)

Attitudes were slow to change at Wake Forest. In the same issue of the Old Gold & Black that reported on the students’ arrest, another story reported that the admissions office had rejected the application of a Black student, as required by the Board of Trustees. Shortly after the sit-in, 55% of Wake Forest students voted to keep the College segregated.

But in 1961, the faculty urged the trustees to integrate the College. A year later, the trustees voted to accept Black students. A student group had been advocating for the admission of Edward Reynolds (’64), originally from Ghana, and he became the first Black full-time undergraduate in 1962.

Johnson went on to graduate from Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. He spent most of his career in clinical pastor education training chaplains in hospitals in the United States and in Sydney, Australia.

His “criminal past” caught up with him a couple of years ago when he was entering Canada. Although he’s traveled around the world, including several previous trips to Canada, no one had ever asked him about his arrest until then. After assuring Canadian officials that he wasn’t a criminal, he was allowed into the country.

“Times have changed for the better,” he wrote in his letter to Wake Forest Magazine. “But not enough. We have a long way to go. We all must do a little whenever we can to stand for human rights and equality.”

Related links

“I’m Not My Brothers Keeper: Leadership and Civil Rights in Winston-Salem,” a 2001 documentary on the sit-in.

Wake Forest and WSSU mark 60th anniversary of sit-in.

Wake Forest and WSSU celebrate 40th anniversary of sit-in.

Bill Stevens (’60), Margaret Ann Dutton Stevens (’60) and George Williamson (’61, P ’94) on the 40th anniversary of the sit-in.

George Williamson (’61, P ’94) remembers the sit-in. (From Wake Forest Magazine, 2009)

Students took the fight for integration to Winston-Salem lunch counters 60 years ago. (From the Winston-Salem Journal, 2020)

Bill Stevens’ interview by Sarah Yaramishyn Nolin (’00) in 1999.

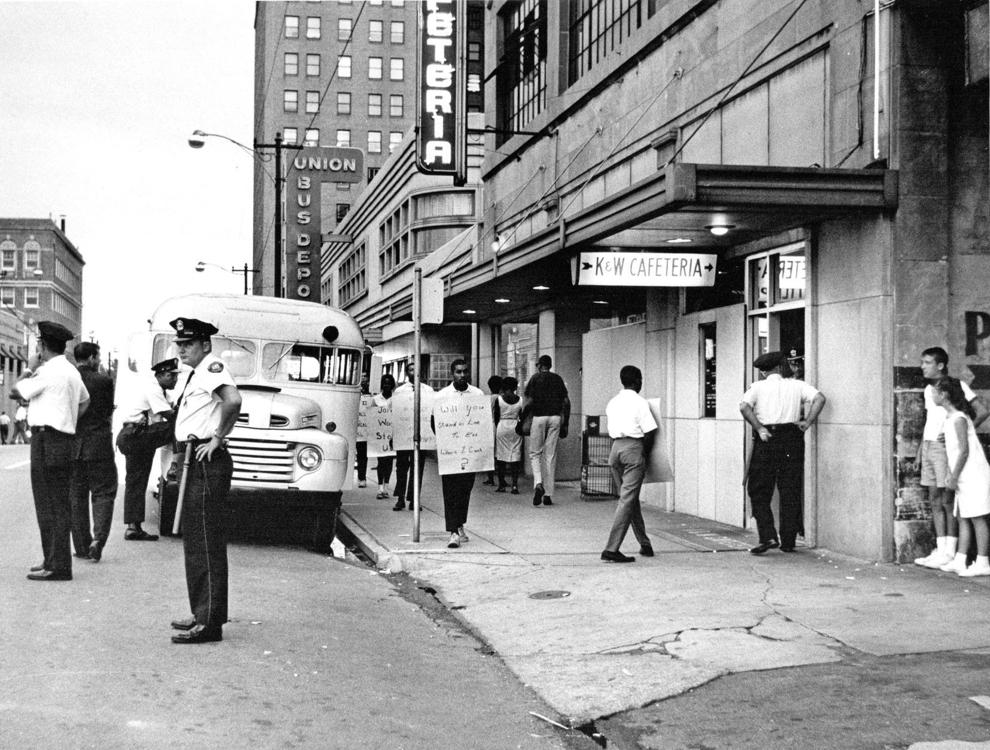

Civil rights activists march outside the K&W Cafeteria in Winston-Salem, circa 1960s. (Photo: Winston-Salem Journal)