Kasha Patel (’12) works in two different, but overlapping worlds: By day, she’s a science journalist, covering climate change and the environment. At night, she’s a stand-up comic, telling “science jokes” at comedy clubs in the Washington, D.C., area and hosting science comedy shows. (After COVID canceled in-person appearances last year, she performed more then 150 virtual comedy shows.)

After eight years at NASA, she joined The Washington Post this summer as deputy weather editor of the Capital Weather Gang. In her first two months at the Post, she’s written stories on Hurricane Ida, an eclipse on Jupiter, melting on the Greenland ice sheet and the earthquake in Haiti. She’s taking her comedy appearances back on the road again this fall.

Patel received the 2019 Young Alumni Award from the Wake Forest chemistry department. Read more about her at kashapatel.com and follow her on Twitter @KashaPatel.

Kasha Patel at the DC Improv Club in Washington.

Weather is driving so much of the news and our lives today, whether it’s a hurricane or floods or wildfires. Can you talk about the importance of weather in our daily lives, beyond “It’s going to rain today”?

It’s incredible how important environmental stories are now. Extreme weather has ramped up in recent years. We’re seeing more droughts, more heat waves. Heat waves are also breaking records by higher margins. We saw that in the Pacific Northwest heat wave earlier this summer. You’re seeing flooding that’s a lot more intense. You’ve seen that in Tennessee and Germany this summer. We’ve had some of the worst wildfire seasons that we’ve ever had in terms of the amount of acres that are getting burned and in the size of the fires. Hurricanes are getting more intense. The stronger ones are getting stronger, and they’re also moving slower. If they’re moving slower that means they can dump more rain in an area, which is what happened with Hurricane Harvey off the coast of Texas. The trend that we’re seeing is global temperatures rising, but it shows up in so many different ways — more heat waves, more droughts, sea-level rise and even rain on the summit of Greenland.

What do you say to people who don’t believe in climate change?

I don’t think it’s that simple that people don’t believe in climate change. People recognize that all these extreme events are happening, are happening more often, and they’re getting weirder. I think it’s parsing out what’s causing those things. People are getting more aware about what’s going on in the environment. That’s why this kind of environment coverage, climate coverage, extreme weather coverage is an important topic. I’m proud to be covering this topic. There are so many different facets to it, which is why we have so many people at the Post writing about it. You can see how it (weather) impacts the health side, financial side and, of course, the environmental side. There are so many different aspects of these extreme weather events that it affects people in at least one way, if not several ways, so that you can get them to care about it.

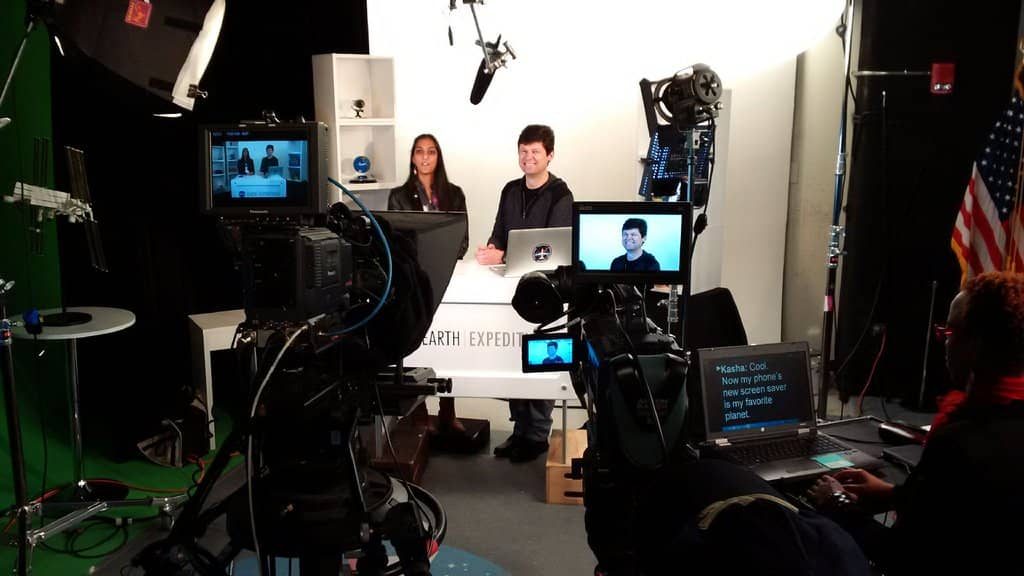

Kasha Patel films an episode of NASA TV's series “Earth Expeditions.” (Photo courtesy of NASA)

How do you communicate often-complex science stories to the public?

I have a double whammy there because I do that during my day job as a writer, but then I also do that in my nighttime passion, stand-up comedy. Both of them are similar because both are ways of communicating. You have to make sure people understand what you’re saying. Comedy is kind of a step above that because if they don’t understand what your premise is, if they don’t understand what you’re saying, they’re not going to understand the punchline. So the No. 1 thing is to communicate whatever you’re talking about — something about your life or a complex science topic — in a pretty easily digestible way.

I like words a lot. There’s something beautiful about how you can write the words, the length of the word, the way that it rolls off the tongue, even if you’re reading it, you’re saying it out loud in your head. I’ve really appreciated words more recently in my career and being able to write something that someone would be able to enjoy. There are a lot of really complex science studies out there and they have important messages, but you can get kind of tied up in (the studies). It’s about finding the right, I don’t want to say hook because that sounds cheesy, but it’s finding that right link to bring somebody into this world.

When did you first become interested in science and writing?

I’ve been interested in science since I was a little girl. I studied chemistry at Wake Forest and was going to medical school, but I hadn’t taken the MCAT yet. I had a yearlong gap and enrolled in science journalism for grad school (at Boston University). I really enjoyed it because nothing felt like homework. It just felt like the stuff that I wanted to do. Everything I wrote had a real-world implication.

My interest in science journalism goes back to my Wake Forest days. I took a reporting class with (Professor of the Practice in Journalism) Justin Catanoso (MA ’93), and I was trying to figure out something to write about. He said, “What interests you?” And I said, “Well, science.” I’m a chemistry major, but why would anyone outside of the department want to read about chemistry without a connection to the real world? One of my first articles was about these chemistry professors making beet juice. That gave me the confidence that I could make science journalism into a career.

My mentors at Wake Forest were extremely valuable, both in the journalism department and in the chemistry department, and during my internship in the Office of Communications. Wake Forest connects so many smart people to make a difference. You don’t have to be No. 1 in your class. I’m glad that I can represent Wake Forest and hopefully make Wake Forest proud.

Kasha Patel makes a presentation for NASA at the American Association for the Advancement of Science. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

How do you use comedy to spark interest in science?

I’m trying to get comedy to a whole new nerd level. I joke about nerd stuff, and the way that I analyze my comedy is pretty nerdy. The thing I like about comedy is that there’s a great power to unite different groups, and because of my interest in science, it felt natural to want to joke about science.

As I got into it, I had to ask myself, what is the purpose of these jokes? Who is the audience? I’m not going to have an audience of scientists all the time. I had to adapt my jokes to be understandable to the general public. I would test my jokes, and what I learned is that if I can make a non-scientist laugh at a science joke, the scientist will also laugh at that joke. If I could make a non-scientist laugh, then I knew immediately it was a good joke.

There’s a TEDx talk where I analyze my jokes. Which jokes do better, my science jokes or my non-science jokes? Which jokes are most effective in terms of producing laughter compared to how long it took me to say the joke? So you get this “joke-efficiency ratio.” What I learned was that there’s so much potential to have science comedy be more general than just for scientists or nerd culture.

I understand that you’re working with some researchers on a scientific study using your science jokes to assess how perceptions affect audiences’ reactions.

“There’s not a lot of research testing how to communicate science in a funny way, but I found a few researchers around the country who actually study science communication. I approached them, and together we brainstormed some study ideas using my good-old science jokes. I had four other comedians tell them (science jokes). They were different demographics, different genders and (were identified) differently as a scientist versus a comedian. We had people watch these videos (and measured) how they responded to the act based upon how the person looked, whether the performer was identified as a comedian versus scientist, and also how likely they were to engage with science after they heard science being pulled in this kind of funny way. I was pretty excited that this thing that I started in a dingy old bar when I was in grad school in Boston is actually being useful in the science research world.

I’m going to put you on the spot. Quick, tell me a science joke.

My comedy career is a lot like climate change. It’s pretty unbelievable, even though there’s evidence of it occurring all around us.