Isaac Sims ('75) on campus in October. Photo by Ken Bennett

When Ike Sims (’75) accepted a scholarship to Wake Forest at age 26 and took on a newly created role advising Black students, he didn’t talk about his military service.

Even today, the Winston-Salem native glosses over that 18-month tour of duty in Vietnam. “I was a security specialist in the Air Force, and … was over there and, you know, had a Purple Heart war wound and a little Bronze Star for valor.”

Even his adult children didn’t know about his medals until a year ago, and only with prodding does he elaborate on what earned him that “little Bronze Star” — jumping from a helicopter and taking a bullet as he airlifted wounded soldiers during a firefight. Talking about it brings back combat stress memories. What’s important, he says, is that a boy, especially a young Black man, who grew up in the shadow of Wake Forest could bring home what he learned in the military and graduate as a Deacon.

Sims likewise understates what he did for other Black students at Wake Forest during a contentious time in American history: “I wasn’t a leader. I was just an asset.” Yet he was one of the few Black adults on campus who could help students navigate housing, academics, financial issues, unfamiliar terrain and racial bias.

Paullette Foman Everett (’77)

Paullette Foman Everett (’77) says Sims “provided me balance, direction and focus on purpose.” Coming from a predominantly Black high school in Washington, D.C., she found that her guidance on what to expect in college was severely lacking, even though she had been in a high-achievers program.

“I had just turned 17 when I came to Wake in January (1974), mid-year,” says Everett, whose cousin attended Wake Forest. “I was in a single room. I tried to fit in as best I could. I look back 50 years later and say, ‘That was insane.’ I really was not prepared.”

She graduated in 3½ years and later was an early leader of AWFUBA (Association of Wake Forest University Black Alumni).

Everett, CEO of NICHE Strategic Marketing in Winston-Salem, wrote that Sims “was a calm, patient, practical leader, even in the midst of a (perceived) storm. One of my all-time heroes.”

Christian Burris (’93)

Sims agreed to share his story at friends’ urging. His godson, Christian Burris (’93), serials acquisition coordinator at Z. Smith Reynolds Library, reached out to Wake Forest Magazine. Sims was “just family” until Burris learned later in life about his godfather’s accomplishments and civic work. In 2002, Sims received the Order of the Long Leaf Pine from then-Gov. Mike Easley, the highest award given by North Carolina’s governor.

“It’s a very modest aspect of his personality,” says Burris, who is secretary of AWFUBA. “He is very outgoing, very gregarious, but he doesn’t focus on those aspects of his life.”

From the 1973 Howler

A military family

Isaac Hayes Sims was named for a relative, not the famous Black singer and actor, who was only four years older than him. Sims’ father worked for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco, and his mother cooked and did domestic work. Sims is the youngest of seven children.

He had an offer to play football at Winston-Salem State University but wanted to pursue other historically black colleges, and “competition was really, really heavy,” Sims says.

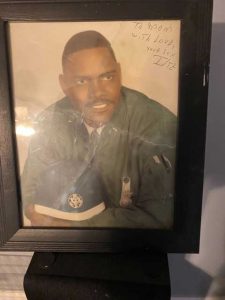

Sims in an Air Force portrait

“So I did the thing that in my family we do — we go in the military.”

He and his three older brothers contributed a total of almost 100 years of military service. His oldest brother, a medic, was wounded in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. The next brother served in Vietnam in the U.S. Navy. His closest brother, a Marine, did three tours in Vietnam.

Ike Sims joined the Air Force. As a security specialist, he protected pilots, airplanes and facilities, gathered intelligence and conducted search-and-rescue operations.

In the mission that led to his medals, Sims was called to help two men trapped in the bush. “We couldn’t completely land the helicopter, so somebody had to jump out, and the biggest and strongest guy turned out to be me,” Sims says.

He leaped 8 feet to the ground to get harnesses on the injured men so they could be lifted out of the firefight. “We were able to save them. That was just my duty, that’s all. It wasn’t anything special because we did it all the time. You just don’t get shot all the time.”

With adrenaline pumping, he didn’t realize he had been wounded. “When we got back, we were getting them off (the helicopter), and the guy said, ‘Is that your blood or somebody else’s?’ I’m saying, ‘Where?’ I looked, and I said, ‘Well, that doesn’t feel good.’”

The bullet penetrated about an inch and half into his left side — fortunate, he says, since it could have nicked his liver on the right side. “They bandaged it up, put a little antiseptic on it. That’s what we did, and I never thought anything else about it.”

Back in the United States, Sims was assigned in Texas to the presidential honor guard for Lyndon B. Johnson when he was home. Then Sims served in the U.S. Embassy in Norway. He was ready to sign re-enlistment papers with the promise of duty in Adriana, Italy. A friend in personnel warned him he would get 30 days of leave, then go straight back to Vietnam.

“I just couldn’t do it, so I got out. That was in 1968,” Sims says.

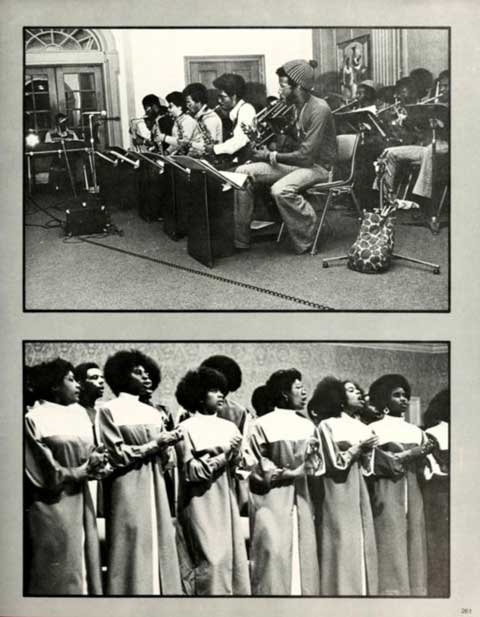

From the 1973 Howler pages on Black Awareness Week on campus.

‘We did some good there’

Sims and a friend, also fresh from the military, found jobs at Experiment in Self-Reliance (ESR), a nonprofit in Winston-Salem. Sims worked in Operation Mainstream, guiding unemployed men, often day laborers, to tutoring, night classes, counseling, substance abuse help, even advice on hygiene and how to do interviews.

Sims said the project placed about 75% of the men in sanitation, highway work, county jobs or hospitals. “Some of them are retired from the city. We did some good there,” he says.

He began doing community organizing in his off hours.

Psychology professor David Hills (P ’83), who also worked in counseling and administration, brought Sims to Wake Forest. This is a 1973 Howler photo of Hills.

“We’re in the 1968 turmoil going on in Chicago (riots at the Democratic National Convention). The Black Panther Party was firing up here, so our goal as organizers was to help keep the political thing going in the right direction without the violence.”

He lost his job at ESR when funding was reduced. Executive Director Louise G. Wilson paid for three classes at Winston-Salem State to get him back in school. “I aced all three, and I said, ‘Hmm, that’s not too bad.’”

Wilson connected him with the Rev. Jerry Drayton, a civil rights activist, who brought Sims to a youth retreat with white and Black students. “We were going to go out in the woods and kumbaya and have a good time,” Sims recalls.

He found out later that the late David Hills (P ’83), who taught psychology and worked in counseling and administration at Wake Forest, was at the retreat and saw Sims’ rapport with students as he told them what he had learned in the military.

Protesters opposed to the Vietnam War and others clash with police in riot gear amid smoke at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Paul Sequeira/Chicago Daily News © Sun-Times Media, LLC. All rights reserved.

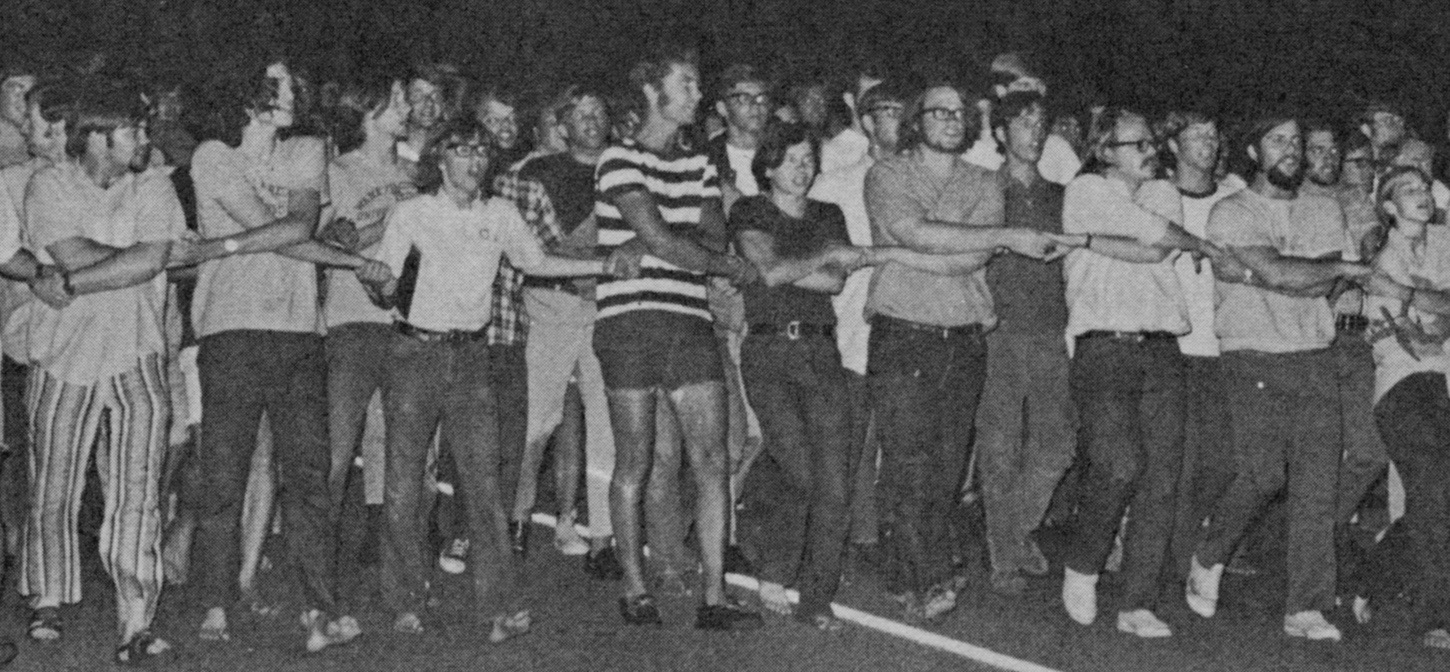

Wake Forest students walk locally to protest the Vietnam War.

An offer too good to refuse

A few years later, Hills was adviser to Sims’ first wife, who had transferred to Wake Forest. Hills asked her if she knew a guy named Sims.

“She said, ‘Yeah, I know him pretty good. I’m married to him,’” says Sims.

The late Robert A. Dyer (P ’89), a religion professor and associate dean of the College, in a 1973 Howler photo. He received the University’s highest honor, the Medallion of Merit, in 1985.

Hills offered tuition for Sims and his wife and a stipend if he would advise Black students. “There’s nobody they can look up to or talk to,” Sims says Hills told him. Wake Forest was the first major private Southern university to racially integrate in 1962 but had no Black tenure-track undergraduate professors until 1974.

Sims struggled to qualify for admission. His summer calculus class “was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. That was harder than being in the military. Because I knew if I don’t pass it, I don’t get in.”

He came up two points short, and he says math professor Gordon May (P ’92) agreed to pass him if he promised not to pursue math-related studies, “no accounting, no business, no nothing.”

Sims agreed and came to Wake Forest in 1972. He worked out of the office of the late Robert A. Dyer (P ’89), a religion professor and associate dean of the College who worked with students facing academic or personal difficulties and international students.

“If a student had an issue with the University or something that they didn’t feel comfortable talking to anyone else about, they could come to me,” Sims says.

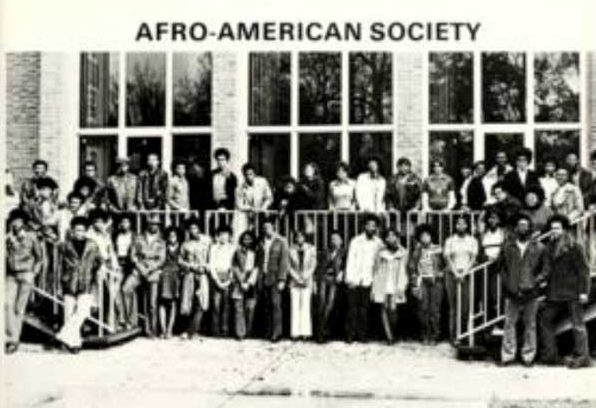

Afro-American Society in 1976 Howler

Supporting Black students

Mütter Evans (’75). Below, in the 1974 Howler.

Mütter Evans (’75), who went on to own a radio station in Winston-Salem, says she was able to find her way, but many Black students needed support. Other than Dyer and a few others, “you didn’t have anyone to advise and look out for you.”

Everett says, “He doesn’t push people to a path, or his path. He wants you to walk your path. … Wake was lucky to have Ike, and I was lucky to have him and build a lifelong relationship.”

Sims says several female students sought his counsel after they were sexually assaulted. The perpetrators were found and kicked out. “There were some racial incidents, like the urine (buckets left behind doors to be knocked over when the door was opened),” Sims says.

were some racial incidents, like the urine (buckets left behind doors to be knocked over when the door was opened),” Sims says.

“Dean (of the College Thomas) Mullen (P ’85, ’88) and Dean Dyer, they were always Johnny on the spot to help get things resolved.”

William Starling (’57)

He says the late William Starling (’57), who became dean of admissions and financial aid, had an open door for students with money challenges.

Sims recruited students. He helped find office space for the newly formed Afro-American Society and funding for the Gospel Choir’s robes. He introduced Black students to local churches and fraternities and sororities at Winston-Salem State.

He also had a degree to pursue, majoring in sociology. “I spent a lot of time in the stacks at 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning because I couldn’t study at home because the baby would be crying.”

Isaac Sims ('75) walks on the Quad with his goddaughter, Candice J. Burris (MAHS ’21), who is academic coordinator in the Department of Communication at Wake Forest. She is the sister of Christian Burris ('93). Photo by Ken Bennett

Effects of Vietnam

Sims thinks he might have been the first Black veteran of Vietnam to graduate from Wake Forest, but such records are hard to come by. Many veterans didn’t talk about the war, given the heated opposition. “We didn’t get ‘thank you for your service.’ We got ‘you’re a baby killer,’” Sims says.

Sims in 1974 Howler

He says he struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder and almost fell into alcoholism. Angry with the U.S. government, he burned his medals. But his brothers, who all faced war trauma, counseled him.

Graduation was a profound moment for him, and for his mother, who had a third-grade education. “It was the proudest day of her life,” he says.

He worked first in regional sales for Clairol hair products — “Miss Clairol Born Blonde and all that,” he jokes. But he found his passion in the Winston-Salem federal building, where he worked in a state office there, fighting for federal disability benefits for North Carolina veterans. He retired after three decades.

Sims is as proud of his three children as his mother was proud of him. His daughter is a clinical therapist who founded a wellness and yoga center in Charlotte. A son works in financial aid at Catawba College in Salisbury, North Carolina. His youngest son is a chef. He says his wife, Angela, keeps him prudent in his urge to help every forlorn person he sees on a sidewalk.

When asked his advice for Wake Forest, Sims says: Don’t deny the existence of any problem. “Whether it’s racism or any kind of issue, address it in a manner of your mind first. You talk. You have a meeting of the minds. Let harsh words and rhetoric be the last thing you want to use because all that does is open up more harsh words and rhetoric.”

Learn the history of Black activism on campus at the AWFUBA/African American Studies Homecoming Lecture, a webinar at noon Oct. 27.