Christopher Zaluski (MFA '13)

When people hear the word “fresco,” says artist Christopher Holt, they think of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, the cracks in the stone, the hand of God reaching to touch the hand of Adam. And if they are like Holt, they grew up thinking of Jesus with “honey brown hair, blue eyes, European Jesus, with this very contemplative gaze on his face.”

If they visit the fresco that Holt painted at the Haywood Street Congregation in Asheville, North Carolina, they will see a very different interpretation of holy figures — represented by people who were or are without homes, with addiction and health struggles, with the scars of the mean streets.

Filmmaker Christopher Zaluski (MFA ’13) has completed a documentary about Holt’s arduous three-year process, including community controversy over making this rare form of art, in an unusual place, with unusual figures.

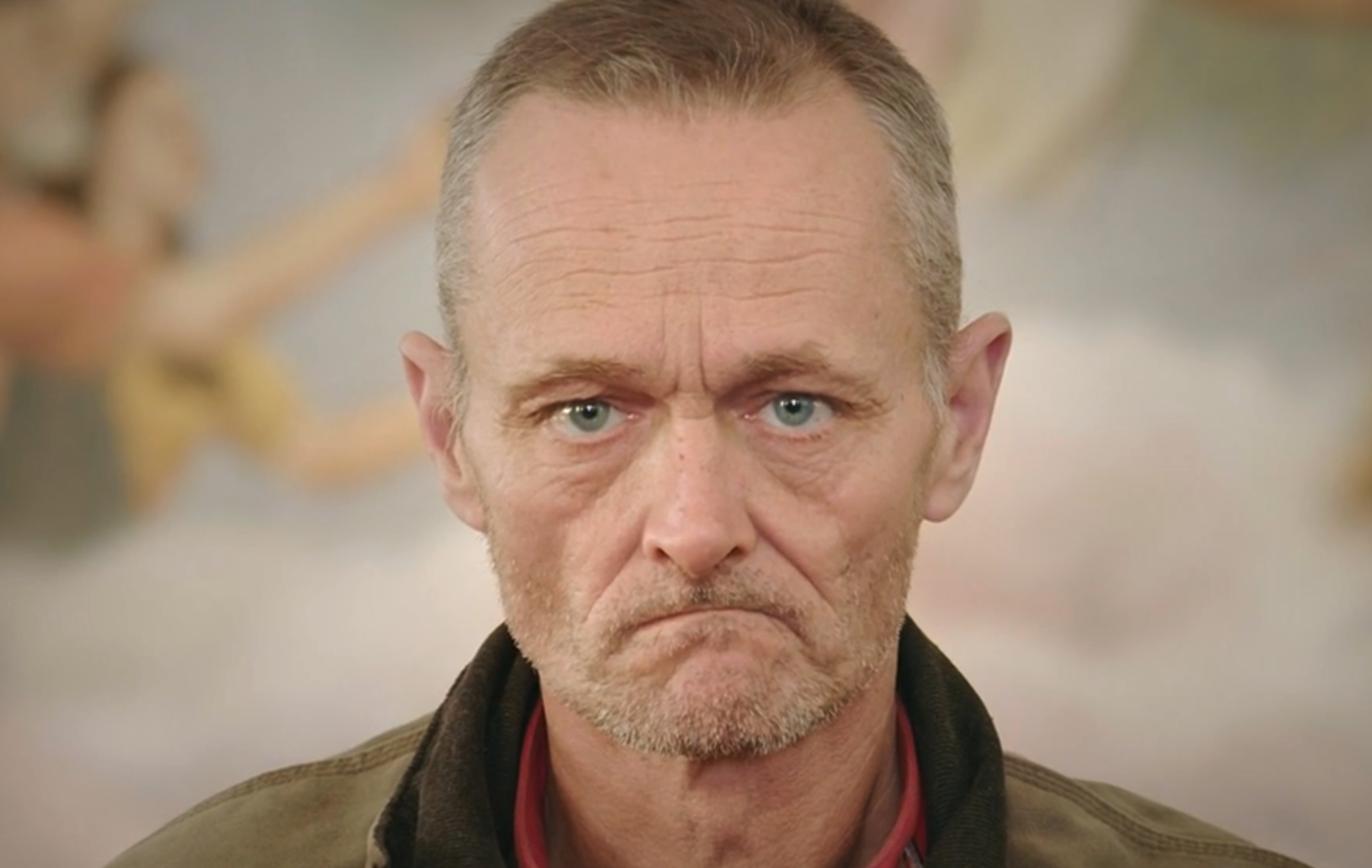

Fresco artist Christopher Holt

Zaluski, an assistant teaching professor in Wake Forest’s Documentary Film Program, will air “Theirs is the Kingdom,” his first full-length film, on PBS at Easter, on April 17. It received the North Carolina Museum of History’s 2021 Longleaf Film Festival award for best overall documentary feature. The North Carolina Museum of Art presented an exhibit on the work, with a reception for those featured in the fresco in March 2020, just a week before the museum temporarily closed its doors during the pandemic.

“I’m a little overwhelmed, I’d say that’s the feeling. Hard to believe,” Dave says in the film, biting his lip to push back tears as he sees his portrait sketch on the museum wall. He once had no home and now cooks at Haywood Street.

Haywood Street Congregation in Asheville, North Carolina

Brian Combs, founding pastor of Haywood Street, a United Methodist Church in what is dubbed Asheville’s “homeless corridor,” says in the film, “From the beginning, we said we want to be a place that welcomes those who are not welcome anywhere else. … We want to say, ‘This is your church. We want you here first.’”

Rev. Brian Combs, who happens to have a Wake Forest connection through through his sister, Diana Combs Roberson (MD ’07).

These are the same kinds of marginalized people Jesus wrapped in his embrace, Combs says. Having Holt draw and paint them, seeing their images immortalized upon a wall in a holy place and having Zaluski interview and film them was a gift, Combs and the fresco’s subjects say. The fresco represents a departure from historical religious art that was intended to transmit faith but with images that mostly excluded ordinary people, Combs says.

“There is something about looking at another human being that requires acknowledging their dignity,” Combs says. “That’s what I hear overwhelmingly from folks in poverty, … that’s the most painful part, … that if I don’t look at you, it means that I really don’t think you’re a human being. And so here we are in a fresco that’s going to be here potentially for tens of thousands of years, saying, ‘These are the people we need to look at the most.’”

Zaluski was living in Asheville and driving to Wake Forest to teach when he learned about Haywood Street. He began the story as a short doc, but it “grew and grew.”

Christopher Holt says painting the Haywood Street Congregation fresco took only three months of the three years devoted to the full process.

Fresco revival

“Painting contemporary frescoes is extremely rare,” Holt says in the film, with perhaps one or two created globally per year. He says he knows of none being done in “the old Renaissance-style process” that he used.

Holt, who grew up in Waynesville, North Carolina, learned the art of fresco for a decade from Benjamin Long, the informal leader of a modern fresco tradition in the mountains of western North Carolina. Holt has traveled the world making art, but the Haywood fresco is his largest, most ambitious and first fresco as principal artist.

What distinguishes fresco is that the artist literally paints into wet lime plaster with hand-mixed pigments, Holt says. The lime binds the pigment and water to it. “It’s not sitting on the surface. It actually is found, captured and held on the wall, becomes the wall.”

Holt spent seven months drawing portraits in person, four months mixing colors and a year on the composition alone before building the wall in a metal frame to contain the fresco. The actual painting took only about three months.

Zaluski says he was drawn to the symbolism of the medium’s permanence, ensconcing these people on the margins whose stories are rarely told. “There are a lot of metaphors to play with for a film.”

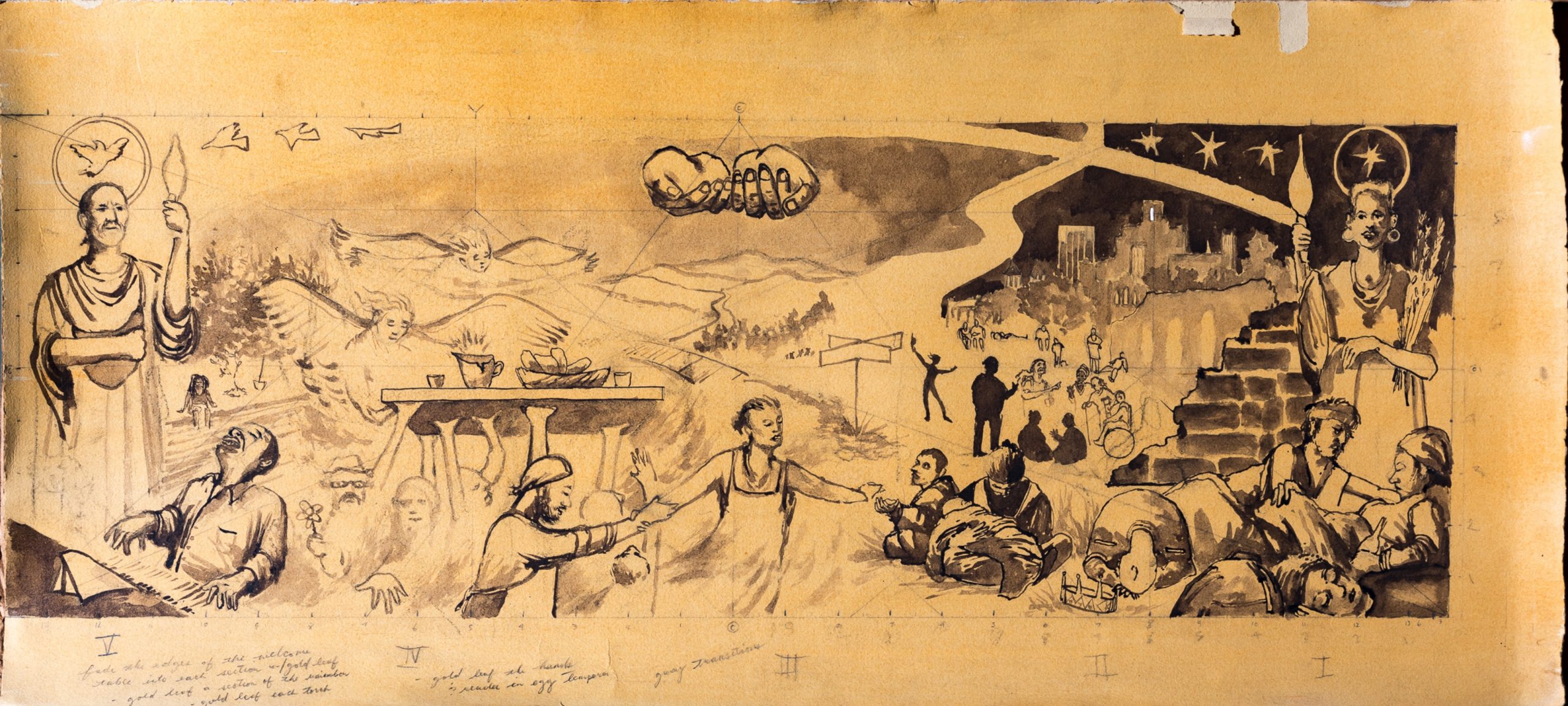

Holt's drawings for the fresco. Western North Carolina has become a unique center of modern frescos.

Resistance and controversy

The Rev. Combs, a minister who has an art and design background, says he and Holt talked about a fresco to give Haywood Street’s members and visitors in poverty something vastly underestimated as human needs — art and affirmation. The Buncombe County Tourism Authority in Asheville, a city nationally known as a magnet for tourists and growth, awarded $72,500 for the fresco project. The grant sparked an outcry and legal efforts to block the mural, in part because public funds were going to a church. Some also argued that the money should go directly to the needy.

Combs says most people in urban ministry and nonprofit work assume that the basics of survival are the most important things to offer those in poverty. “Art and music and love never show up on that list,” he says. “And yet it’s an essential part of how we’re created.”

The church withdrew its grant request and raised the funds privately.

Zaluski filmed fund-raising events in people’s homes as Combs shared the message that poverty, mental illness and addiction take away people’s self-esteem. “If we put someone in a painting that will be there for the rest of eternity, you are saying, ‘In every way, your story matters.’ … Your life matters enough to be put in a painting 20 feet wide and 10 feet tall. And I don’t know of any other art project like this in the world. This is why it matters for me.”

Zaluski says he learned a new way of listening by sitting with people for long periods as Holt sketched them. They slowly began to trust Zaluski and fully speak their stories.

Many were heartbreaking.

Jerry, who suffered abuse and served time in prison, found friendship and support at Haywood Street Congregation.

Untold stories

Jerry, with a stern face and startling, beautiful eyes, opened up about his abusive childhood. His father stuffed his mouth with a rag, tied him to a bed frame or a tree outside and beat him with a motorcycle chain or a two-by-four. He bounced around in foster care “like a beach ball for quite a while.” He served prison time twice and was homeless for 10 years, he says in the film.

He was afraid and nervous to sit with strangers on his first visits to Haywood Street. Gradually, he says, he began to see that others’ stories echoed his. “Why should I shy away from going to somewhere that’s welcoming to me? There’s no need (of) people being scared of sitting down with anyone here at this church. Have a seat with us, carry on the conversation. You’ll see what we’re about.”

Some church members, like Robert Johnson, named for the famous blues musician, are quick with a smile. “My nickname turned out to be Blue. Since I was 2. Going to be Blue ‘til I’m through. And that is true,” he says in the film.

He says he is proud to have turned 60 after living for 14 years with an aneurysm. He shows his folder full of colored pencil artwork. “Sometimes I sit on the side of my bed and do artwork,” he says. “I say, ‘Blue, you are amazing, just the way you are.’ God says, ‘Come as you are.’ And I go as I am.”

Robert "Blue" Johnson, a beloved member of Haywood Street Congregation.

Moving ahead

In late September 2019, Holt completed the fresco, coincidentally on his 42nd birthday. Charles Burns, his first model and an original member of Haywood Street, did not see it, claimed by cancer in 2019. In December, Robert “Blue” Johnson died.

A mural on silver leaf foil by Holt in the narthex of a chapel at Dorothea Dix Park in Raleigh, the project that followed his fresco.

Asked in the film if he would ever do another fresco, Holt says, “I would start today.” As it turns out, he went on to do a mural painted on silver-leaf foil in the narthex of the chapel at Dorothea Dix Park in Raleigh. He is painting silver leaf murals now on the walls of the new UNC Rex Cancer Center in Raleigh.

The fresco continues to attract daily visitors, despite the pandemic, often drawn by seeing Zaluski’s documentary at film festivals. Haywood Street’s next project is a plan to build a 45-unit apartment complex within walking distance to the church.

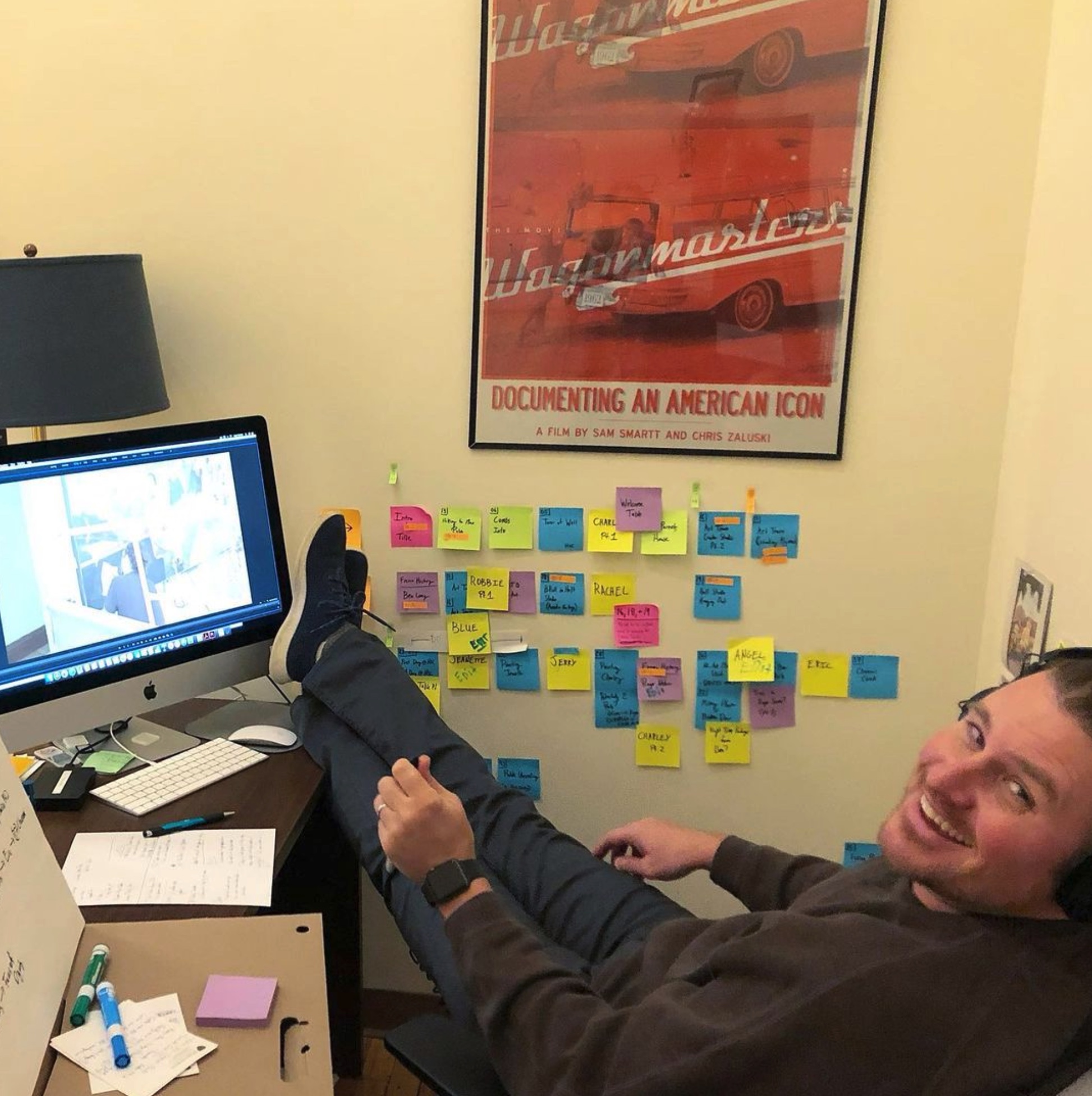

Zaluski is working on new films and distribution of “Theirs Is the Kingdom,” which he says is more work than making the documentary, no small task. Wake Foresters who assisted with the film include University media producer Tom Green (’97, MFA ’16) in editing and sound mixing design, Trey Kalny (’07, MFA ’19) in editing, story consultant Sam Smartt (’09, MFA ’13), assistant editor Andrew Austin (MFA ’14) and film faculty members Sandy Dickson, Peter Gilbert, Cara Pilson and Chris Sheridan.

Students benefit from his learning, Zaluski says. “All the faculty in our program try to bring their lived experiences and their filmmaking experiences from the field into the classroom, because it makes it a lot more authentic.”

The film reinforced for him why he chose to move to film from a newspaper career at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and The Roanoke Times. He loved being a reporter, “but I did feel like I was kind of swooping into people’s lives in some of their hardest moments and then leaving. What I love about documentary is that it allows me to be with people for a longer period of time and create some real human relationships.”

The film is not yet available for streaming, but a trailer, signup for event screenings and film updates are at theirsisthekingdomfilm.com. Zaluski’s previous film about station wagon enthusiasts, “Wagonmasters” with co-director Sam Smartt (’09, MFA ’13), was acquired by PBS, Amazon and Kanopy. More on Instagram @theirsisthekingdom, @christopherholtfineart and @haywoodstreetcongregation or on Facebook @haywoodstreet

Zaluski in his office