B

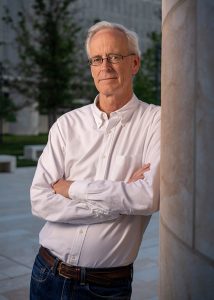

ill Roebuck, former U.S. Ambassador to Bahrain, stands in his airy kitchen in Arlington, Virginia, and shares Netflix-worthy stories from his 28-year career in the U.S. Foreign Service. His soft Southern voice bears no trace of adrenaline in the retelling.

In 2003, an armored caravan ferries Roebuck (’78, MA ’82) toward Gaza City. He and others in the lead car hear a muffled “ploomff” behind them. Attackers have detonated a bomb buried in the road, exploding the car that would have carried Roebuck if not for a last-minute change of plans. Instead, the assassination attempt kills three of the four American security officers in the targeted vehicle.

In 2009, Roebuck travels across Baghdad in another armored caravan to an Iraqi ministry meeting. The next day, al-Qaida explosions blast the 10-story ministry building, killing at least 95 people, injuring 600 and leaving the rubble of blackened cars for blocks. “It looked like Mad Max,” Roebuck recalls.

In 2013, Roebuck oversees the U.S. Embassy in Libya after Islamic militants have attacked a U.S. compound in Benghazi in 2012 and killed Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. Roebuck takes a run around the exterior of the embassy walls on the outskirts of Tripoli. Running alongside him is a security guard who is none too excited about the lanky diplomat’s open venue. But running is Roebuck’s go-to exercise.

Bill Roebuck arrives back at the closed Lafarge cement factory in northeastern Syria, used as the U.S. Special Forces base where he lived from 2018 to 2020. He had flown to Deir a-Zour province for the day. (Photo courtesy of Bill Roebuck)

In early 2018, a C-130 military plane lands at a pitch-black dirt airstrip in northeastern Syria in the secrecy of the wee hours. It delivers Roebuck, a few other people and a pallet of supplies to a remote outpost protected by U.S. Special Forces in yet another war-torn region. Roebuck will work as the senior diplomat, sometimes the lone diplomat, at the complex intersections of tribal chiefs, ISIS terror troops and U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

He tells these tales in the same level tone with which he describes his significant but less overtly dramatic duties, whether securing Libyan approval for a flyover to reach endangered Americans or pushing for the human rights of protesters when he was U.S. Ambassador to Bahrain. Through it all, he walks a tightrope of international and domestic politics.

The question must be asked: Was he scared after finding himself in Gaza a car length away from possible death? “In terms of professional work, I just compartmentalize it, and I went about my business,” Roebuck says. “I’ve never felt afraid overseas, even though things can happen.”

Did it give him pause when he realized he was a calendar appointment away from a major bombing in Iraq? “I mean, I wasn’t in danger. I wasn’t there that day.”

“In terms of professional work, I just compartmentalize it, and I went about my business. I’ve never felt afraid overseas, even though things can happen.”

—Bill Roebuck

Flowers and a memorial banner adorn the remains of vehicles destroyed by bombs in Baghdad. Roebuck had visited the Iraqi Foreign Ministry in the background a day before the bombing on Aug. 19, 2009. (AP Photo/Khalid Mohammed)

A diplomat-scholar

Roebuck’s calm in treacherous environments led the U.S. Department of State to award him the Ryan C. Crocker Award for Outstanding Leadership in Expeditionary Diplomacy for his service in Libya. He also received the Award for Heroism in 2020 for his work in Syria, just as he was reaching the mandatory retirement age of 65.

Photo by André Chung

Eager to continue using decades of knowledge, he transitioned in January 2021 to a new job as executive vice president at The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington (D.C.).

That Roebuck is a man of great courage is true, but it’s the second most striking thing about him, says Jeffrey Feltman, a former colleague and boss, a former U.S. ambassador to Lebanon and now the U.S. Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa, a world hotspot.

The most striking thing about Roebuck, Feltman says, is his talent as a “diplomat-scholar.” Many Foreign Service officers are highly intelligent and master policy wonks, Feltman says, but Roebuck’s talent is rare. He dives deep into the history, culture and anthropology of wherever he is serving and builds a robust context for analyzing policy.

“The scholarly background does not turn him into a bookworm,” says Feltman of his friend. “It turns him into an intrepid, courageous promoter of U.S. interests in some of the most dangerous places in the world. It’s remarkable.”

Feltman might be too quick to acquit Roebuck as a bookworm. An English major with a master’s degree from Wake Forest, a law degree from the University of Georgia and an appearance that could easily pass for a college professor, Roebuck has never slaked his childhood thirst for reading. He has carried volumes of books with him into the world’s deserts.

He is a writer, framing the conundrums of global politics in a literary landscape. His essays win praise for their writing quality and political insights.

“The scholarly background does not turn him into a bookworm. It turns him into an intrepid, courageous promoter of U.S. interests in some of the most dangerous places in the world.”

—Jeffrey Feltman, former U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon

During a year in Baghdad, he chose to use Fridays, his only day off, to excavate meaning from James Joyce’s notoriously challenging novel, “Ulysses.” Roebuck wrangled with it “for a little self-improvement, or at least high-class distraction,” he wrote for the Foreign Service Journal in an essay called “Bloomsday in Baghdad: Reading Joyce in Iraq.”

“Ulysses is a sprawling, confusing, difficult novel, with a narrative arc that never seems to make much progress. A perfect choice for Baghdad,” the essay’s headline noted.

Wake Forest ‘opened new worlds’

The son of an Allstate insurance agent and a homemaker, William Vernon Roebuck Jr. grew up with his two sisters in an eastern North Carolina town that still lingers in his accent. Church and sports — basketball and track — filled his young life in Rocky Mount.

Downtown Rocky Mount, in eastern North Carolina, where Roebuck grew up. (Photo courtesy of Downtown Rocky Mount Inc.)

Books brought new influences at an early age. “I was from a Southern Baptist family but saw myself as a self-styled, little snotty radical,” he says. “It was a backwash of the ’60s. I liked anything that was dissident in some way.”

Older classmates who went to Wake Forest invited him to campus when he was in high school and took him along to classes. “It was a place I knew and was comfortable with,” says Roebuck, who received a George Foster Hankins Scholarship.

Roebuck stops for a moment, surprised by a surge of emotion as he talks about Wake Forest. It opened new worlds to a boy who craved knowledge and dreamed of moving beyond the South’s racial and equity injustices. The University’s Pro Humanitate values took deep hold. “Wake Forest became a part of my DNA. It just shaped the way I see the world, the way I wanted to be in the world.”

He returns to the topic later in the interview, his equilibrium restored, and talks of professors of the time who influenced him. (In a testament to his willpower, he remains standing for the 3½-hour interview, unable to sit because of sciatica requiring surgery last summer.)

At Wake Forest, English professor Lee Potter encouraged Roebuck’s writing. Patricia Adams Johnson Johansson (MA ’69, P ’80, ’83, ’84), associate dean of the College and lecturer of English, mentored him, as did French professor Suzanne Chamier Wixson and then-Provost Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93).

Literature captivated him: The visceral South of William Faulkner, the satire and poetry of Jonathan Swift, the activism of James Baldwin and the Victorian social criticism of Charles Dickens, still a favorite. He read early feminist theory. Professor of Religion George McLeod “Mac” Bryan (’41, MA ’44, P ’71, ’72, ’75, ’82) introduced him to radical church and civil rights writers, including the Berrigan brothers, Daniel and Philip.

Seeds of the Foreign Service

Wake Forest also kickstarted Roebuck’s passport. He mastered French during a seven-week homestay in Switzerland before an undergraduate semester of study in Dijon, France. The Swiss family’s 3-year-old and 6-year-old spoke no English. “I remember the little 3-year-old girl, I was struggling to say something, and she said, ‘Just say it! Just say it!’ That was the breakthrough for me that I had the confidence and the rhythm of it and could build on it.”

Roebuck in the Peace Corps in Sassandra, a coastal town in Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa, where he taught English from 1978-81. (Photo courtesy of Roebuck)

After graduation, he served three years in the Peace Corps teaching English in Côte d’Ivoire, a former French colony in West Africa. “I was basically dreaming in French at that point,” he says.

He lived “way out in the sticks,” five hours by car from Abidjan, the country’s largest city. Every few months he visited Abidjan and discovered the charms of “this mysterious thing that I hadn’t known existed before, which was the U.S. Embassy.”

Unlike the village, “they had cheeseburgers in their cafeteria, and they had a little library. I felt I had to find out how that works.”

He returned to Wake Forest to pursue his master’s thesis on the African novel, advised by renowned scholar Germaine Brée, who added the French intellectual tradition to his repertoire. He focused on Chinua Achebe of Nigeria, South African-born journalist Peter Abrahams and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o of Kenya.

With the travel bug in his blood, he spent five years teaching English in Saudi Arabia, where he met his wife, Ann, a Belgian who is now a U.S. citizen.

“I had already been overseas a lot, and I liked the taste of it,” Roebuck says. “I just didn’t want to do it anymore as a local contractor, where … something goes wrong (and) you disappear into a prison for 10 years and nobody knows anything about it.”

He left Saudi Arabia to tackle law school in the United States. At age 36, with a law degree fresh in hand in 1992, he joined the Foreign Service. He spent two years of rigorous initiation into consular work in Jamaica, often conducting 100 short visa interviews in a morning. A seven-week rotation in the Jamaica political section was closer to the journalism career he had considered when he wrote for the Old Gold & Black.

“I said, ‘This is more like it. I love this.’ That gave me a chance to write, to get out, to see people, to get interested in the developments, what was going on in the country,” he says.

As a political officer at the consulate in Jerusalem from 1995 to 1997, he monitored the high-profile expansion of Israeli settlements in the Palestinian West Bank. “I was off and running after that.”

Stationed back in Washington, he began studying Arabic, more difficult than French, especially at age 41. But he could, without a translator, plumb the stories of activists and imprisoned dissidents courageous enough to give an American the insider’s view under repressive governments.

In Israel again in 2000, he covered Gaza politics. Ann and their son, William, joined him in Tel Aviv. He drove 90 minutes three days a week through checkpoints to meet with businessmen, teachers, journalists and others, until violence in the Palestinian uprising allowed only phone interviews.

Roebuck, back row, right, with another American English teacher and students at a military school in the mountainous city of Taif, Saudi Arabia, about 70 miles from the holy city of Mecca. He taught and was director of the English Department. (Photo courtesy of Roebuck)

An explosive device blew up this U.S. Embassy car in Roebuck’s caravan in the northern Gaza Strip, killing three American security officers on Oct. 15, 2003. In 2004, the United States suspended two water projects worth tens of millions of dollars in the Gaza Strip because the Palestinian Authority failed to bring to justice those responsible for the attack targeting Roebuck. (AP Photo/Kevin Frayer)

Huge crater in the road

Roebuck had resumed trips to the Gaza Strip by 2003 in heavily-guarded caravans of three armored Jeeps, 10 to 15 feet apart. On Oct. 15, 2003, a training mission for new security officers resulted in switching the order of the cars, so he was in the front car instead of a middle car.

As they drove into Gaza, “everybody’s jabbering and talking, telling stories and laughing. Dust blows up on our window first. And then we hear something, but it’s not like a huge kaboom. It was more like a contained ‘ploomff,’ and people were looking, ‘What was that?’”

His car did a U-turn, and they found the flipped car behind them, a crater in the road and the bomb’s gruesome results, fatal for three officers. An investigation did not definitively identify who was responsible, but Roebuck says Palestinians or others he interviewed had no reason to stop him from telling the stories they wanted told. Someone somewhere “just said, ‘Get us an American pelt.’”

Roebuck worked through his emotions without feeling deep scars. “I wrote about it, little pieces of poetry and things trying to come to terms with it.”

In the thick of it

Roebuck served in posts with ever-increasing responsibilities, his assignments bouncing in and out of dangerous places where he would go alone. His family lived with him in the safer cities, including Tel Aviv and Damascus, Syria, before Syria’s civil war began in 2011. William attended American international schools.

“We loved Damascus,” Roebuck says. “It was a police state, but it was safe. It was incredibly rich, historically and culturally.”

Three days of feasts and dancing in Damascus, Syria, in 2007 break the fasting of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. Syria’s beauty and culture, prior to its civil war, made it one of the Roebuck family’s favorite places. Damascene sweets in a shop. (AP Photo/Bassem Tellawi)

A Syrian Mallawi dance group at a restaurant in Damascus. (AP Photo/Bassem Tellawi)

The family returned to Washington in 2007. William, an athletic middle-schooler, “became a very Americanized kid very quickly and never looked back.” He is now 25 and lives in the Arlington area.

Ann, who works at the Foreign Service Institute, shares her husband’s love of living internationally and accompanied him when she could.

Every place has violence, she says, even if it’s one-on-one, rather than the attacks of a landscape in conflict. “We both just really loved the Middle East, so we knew that was our area to be in. We signed up for that together, completely on board.”

The Gaza attack “definitely shook us,” but they moved on, she says. “Then when he went on unaccompanied tours, I’ll tell you, I probably don’t know half of the things that happened.”

The Roebucks were trying to keep family life stable for William, but Roebuck’s superiors required everyone to contribute a stint in Iraq. He took a year’s assignment without his family in 2009 to support Iraq’s critical national elections in March 2010.

“I’m glad I went. But it was just very difficult. It was isolated because you were on this huge triple-, quadruple-secured American embassy compound that just sprawled and loomed.”

Outside meetings required an armored convoy, limiting the number of trips. The day after explosives blew up at the ministry, he ventured back to offer condolences. He saw devastation and glass shards — “it just tears people apart” — spewed across the office where he had chatted the previous day with the foreign minister and his two chief aides, who escaped injury.

“So, Baghdad was dangerous,” Roebuck concedes.

“When [Bill] went on unaccompanied tours, I’ll tell you, I probably don’t know half of the things that happened.”

—Ann Roebuck, wife of William Roebuck

Israeli police detain an Arab Israeli outside the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv in 2002, when Roebuck was posted there. The man was protesting Israel’s military offensive in refugee camps in the West Bank and against armed Palestinians holed up in Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity. (AP Photo/Elizabeth Dalziel)

Libya’s ‘Fort Apache, the Bronx’

Roebuck took over as chargé d’affaires overseeing the U.S. Embassy in Libya in January 2013 after Ambassador Stevens died in the Benghazi attack in September 2012.

Roebuck’s six months in Tripoli were “super interesting,” he says. “I liked managing the embassy. We had a great little team, sort of ‘Fort Apache, the Bronx’. … We had 85 Marines guarding us. Normally in an embassy you have 10. So, it was just overwhelming security and firepower.”

Roebuck met with top Libyan leaders eight to 10 times a week, appeared at cultural events “if it wasn’t too dangerous” and facilitated education grants, Fulbright Scholarships and international visitor programs. He dealt with joint counterterrorism efforts to capture the Benghazi culprits. (In 2017, the Libya militia ringleader was sentenced to 22 years in prison, and a second militant received 19 years in 2019.) Roebuck managed life in Libya on high alert, still running to relieve stress, but with an escort if chatter indicated threats.

“You have to make decisions, and you have to be comfortable with it, and you have to live with it. If you don’t want to do that, you need to go do something else,” Roebuck says. “It was exciting, and I loved it.”

Reaching the goal of ambassador

Roebuck’s courage extended to the political arena. In February 2014, he and other Americans walked out of a Tunisian celebration of its new constitution as Iran’s parliamentary speaker accused the United States of supporting dictatorships during the Arab Spring.

His Majesty King of Bahrain, left, in uniform as official head of his country’s armed forces, joins Ambassador Roebuck in 2016 for a selfie by Vice Admiral Kevin Donegan, who was U.S. Commander of the Fifth Fleet at U.S. Naval Forces headquarters in Bahrain. The Fifth Fleet covers the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Arabian Sea and parts of the Indian Ocean.(Photo courtesy of Roebuck)

Roebuck built his career with an ambassadorship as his goal. In July 2014, President Obama nominated him and the Senate confirmed him for the post to the Kingdom of Bahrain. He arrived in Manama in January 2015.

He walked a diplomatic edge as ambassador in Bahrain in the wake of Arab Spring uprisings. He pushed the king on human rights abuses, but Roebuck also needed to keep military relationships secure with this ally against Iranian influence. He appreciated the “really smart, talented people” in the embassy writing speeches or whispering background in his ear as he met people. “It was a joyful three years.”

Stephanie Hallett worked with Roebuck in Bahrain. She is in Washington but most recently was deputy chief of mission in the U.S. embassies in Cyprus and Oman.

“He’s the best kind of leader that you want leading an embassy,” she says. He was “thoughtful in everything that he approached, really, really wanted to understand issues, was equally decisive, … empathetic, … very humble (and) on top of that, someone who is visionary.”

Roebuck, Feltman says, “comes across as a really decent Southern boy, … as just someone you love to have a beer with, but he’s also someone that you can sit down and listen to really deep analysis about poetry, about literature, about how these things are still relevant today, how these could inform what we’re doing in our foreign policy.”

Roebuck’s superior asked him to leave Bahrain early for a Washington project, with another Middle East ambassadorship to follow. But two nominations stalled internally in the State Department in 2017, Roebuck says. There was a new administration and “a certain degree of Benghazi backlash,” given extensive, lengthy investigations and associated political divisions.

A civilian watches fires set at an Islamic militant base in Benghazi, Libya, on Sept. 21, 2012. Hundreds of frustrated locals, military and police raided the base 10 days after militants attacked two U.S. compounds in Benghazi and killed U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. (AP Photo/File)

Pursuing hope in a desperate land

As Roebuck and his superiors worked on finding him a new role, his boss suggested a week in northeast Syria in early 2018 to advise the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). They were trying to start a political party to ensure that people in the region were represented in the growing political opposition to authoritarian President Bashar al-Assad.

The pilots wore night-vision goggles to land at the darkened airstrip where U.S. Special Forces collected Roebuck in a beat-up Toyota Land Cruiser. They drove 40 miles, depositing him at 3 a.m. at a makeshift post for American and SDF forces in an abandoned cement factory.

The challenges hooked him. His stay extended to 2½ years, with a title added: Deputy Special Envoy to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. It was a dangerous time. Turkey was trying to oust the Kurdish rebels in northeastern Syria who were pushing out much of the Islamic State from its stronghold. Reports of another chemical attack in early 2018 prompted U.S., British and French airstrikes on the Syrian military, suspected as the culprit.

Students at a refurbished school in Raqqa, Syria, in 2018. (Photo courtesy of Roebuck)

Roebuck traveled with the protection of U.S. Special Forces, sometimes in Black Hawk helicopters. Impressed tribal leaders introduced him as “His Excellency Ambassador Roebuck.” He added diplomatic heft to military efforts to persuade locals to align with American forces.

He worked to help the region recover from the ravages of eight years of war, restoring water and electrical services, irrigation canals, grain silos and buildings damaged, sometimes inadvertently by Americans. The urban battlefield of Raqqa haunted him with its ragged echoes of Dresden, the German city bombed almost to oblivion in World War II. He kept up his efforts even as the U.S. administration in 2018 cut off funding for rehabilitating Syria and pressured European and Arab allies to assume the costs.

The politics were byzantine, but his diplomacy often succeeded. He was the lone diplomat to speak at a ceremony celebrating the surrender of 10,000 ISIS fighters in the Battle of Baghouz.

He had waded into a morass in search of a role, and he had made a difference in a desperate place.

“He’s the best kind of leader that you want leading an embassy. [He was] thoughtful in everything that he approached, ... was equally decisive ... empathetic ... humble [and] on top of that, someone who is visionary.”

—Stephanie Hallett, former colleague of Roebuck

In 2019, the Trump administration announced it was withdrawing U.S. troops from northern Syria. Turkey promptly initiated a deadly incursion. American forces stood by, unable to protect Kurdish and SDF troops, even though the U.S. military and Roebuck had enlisted their help to vanquish ISIS and had promised not to abandon them.

Military helicopters evacuated Roebuck, Special Forces and contractors from their cement-factory base. Fires raged around them as SDF set its armory ablaze to keep it from the hands of Turkish-backed militias.

Roebuck didn’t deny when The New York Times published a leaked internal memo in 2019 in which he argued that the Trump administration had done little to discourage Turkey’s incursion. Roebuck, a career officer through multiple U.S. administrations, publicly acknowledged later that Trump had repaired the damage to relations with the SDF by agreeing to keep troops there, though Roebuck noted that the United States had, practically overnight, lost half the territory it had gained.

Bill Roebuck poses at the new Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, D.C. Roebuck admires the 34th U.S. president and commander of the Allied Forces in World War II, whose goal was to build “a peace with justice in a world where moral law prevails. (Photo by André Chung)

Literature as insight

The gains and losses in war and diplomacy would demand a respite for anyone. For Roebuck, renewal came through immersing himself in literature and writing. He crafted lively dispatches that opened career doors. “I made my name as a writer doing these cables,” he says.

Most restorative in faraway locations were reading projects he assigned himself: tackling all of Faulkner’s works or “Ulysses” in Baghdad.

Roebuck digested Dante’s “Inferno” in Syria. As he toured twisted wreckage in Raqqa, “I was seeing a vision of Dante’s hell before my eyes,” he wrote in the May 2021 Foreign Service Journal.

Roebuck answers media questions in Deir a-Zour governorate in Syria after meeting with Sunni Arab tribal leaders and the Deir a-Zour civil council. (Photo courtesy of Roebuck)

Frederic C. Hof, a former ambassador and special adviser on Syria, said in the Journal’s letters to the editor that he had never read anything better on Syria in 10 years. “I was stunned by the author’s eloquence and insight,” wrote Hof, a professor and diplomat-in-residence at Bard College.

In another letter, Ronald E. Neumann, former ambassador to Algeria, Bahrain and Libya, said the piece captured what a great Foreign Service officer does. “He reports in a way that grabs the reader, that compels understanding of the foreign view, and that lays out what needs to be done as a policy matter for the United States and why it needs to happen. To do so with brevity and clarity is professionalism. To do it with beauty is art.”

Roebuck says in an essay in Defense One online that diplomats sometimes must resort to “pocket-lint diplomacy: the effort to mediate, persuade, cajole, assist, and reassure as if one’s diplomatic pockets were full of expected solutions and commitments, in the full realization one’s pockets, except for the lint, were empty.”

But an effective diplomat can “work some magic” by listening, empathizing, improvising and maintaining “confidence in the might, prestige and values that the U.S. brings to the foreign policy table,” he says.

At The Arab Gulf States Institute, Roebuck is finding a new role, speaking at conferences and overseeing essays and papers. He continues to write.

In a reflection shared with Wake Forest Magazine, he says the University formed a foundation for his life and profession. “Those long-ago struggles at Walden Pond, or contending with Faulkner’s “Light in August,” … or waging a protest for student dorm rights … — all of it created the palimpsest upon which I have over the years written and rewritten my career,” Roebuck wrote.

“I ended my career with yet another version of myself, written like all the others on that sturdy undergraduate parchment that Wake Forest helped me first write for myself.”

Roebuck with U.S. military on a visit in the Deir a-Zour area in 2019. (Photo courtesy of Roebuck)

"[Roebuck is] one of the best expeditionary war zone diplomats I have seen in my career ...”

TOP: Roebuck worked with an elite group of U.S. Special Forces, who made an American flag from scrap wood, overlaid stars on it and gave it to him. BOTTOM: Arab tribal leaders in Syria presented Roebuck with the sword and the curved dagger circa 2018. Closest to the sword is a straight dagger confiscated from an ISIS fighter arrested by Syrian Democratic Forces. Roebuck purchased the inlaid chest in his earlier assignment in Damascus from the Souk al-Hamidiyeh market. (Photos courtesy of Roebuck)

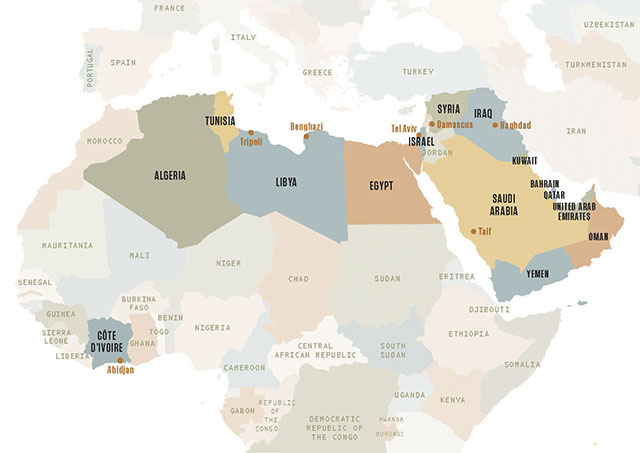

Career Timeline

Source for country references: CIA.gov The World Factbook.

1978-1981

Peace Corps, Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa

1982-1987

English teacher and school administrator, Taif, Saudi Arabia

1992

Law degree from the University of Georgia. Joined the State Department

1992-1994

Consular officer, Kingston, Jamaica

1995-1997

Political officer, U.S. Consulate in Jerusalem

1997-1998

Staff assistant to assistant secretary of Near Eastern Affairs

1998-2000

Studied Arabic, Foreign Service Institute in Washington, D.C., and Tunis, Tunisia

2000-2003

Political officer, U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv, Israel

2004-2007

Political counselor and later acting deputy chief of mission, U.S. Embassy in Damascus, Syria

2007-2009

Deputy Office Director, Arabian Peninsula Affairs (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen)

2009-2010

Deputy political counselor, U.S. Embassy in Baghdad

2010-2012

Director, Office of Maghreb Affairs (Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia)

2013-2014

Chargé d’affaires, U.S. Embassy in Tripoli, Libya. Deputy assistant secretary for Maghreb Affairs and Egypt Affairs

2015-2017

U.S. Ambassador to the Kingdom of Bahrain

2018-2020

In Syria as Deputy Special Envoy to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS

2020

Retired from Foreign Service in the U.S. State Department after 28 years

2021

Executive vice president, The Arab Gulf States Institute of Washington (D.C.), independent nonprofit