Dan Morrill (’60) walked quickly behind his rolling walker through the patchy grass to the front of a 1937 Tudor Revival stone mansion along Sardis Road in Charlotte. Pausing briefly to carefully step up to the flagstone patio, he rolled on through the front doors and into a grand foyer with a limestone floor, double staircase and stunning stained-glass window.

“Look at that,” he says, marveling at the elaborate interior. “This is an extraordinary piece of architecture for Charlotte, designed by an architect of note.” His February visit was the first time he saw the James Jones Akers and Nancy Anderson Akers house in person, although he’s worked for several months to ensure that it will be preserved forever.

Morrill, now 84, was born the same year the Akers house was completed. “We were both brand spanking new then,” he says. But the retired UNC Charlotte history professor isn’t slowing down — the walker certainly doesn’t slow him down — to preserve as much of Charlotte’s built-history as he can in a city that worships the new, not the old.

Stained-glass window on the landing of a double staircase in the James Jones Akers and Nancy Anderson Akers House in Charlotte, completed in 1937. <br />

Morrill has been helping preserve historic properties in and around Charlotte for half a century. Charlotte Magazine once described him as “Charlotte’s undisputed expert on and leader in historic preservation.” Realtor John Springsteed, who worked with him to save the Akers house, calls him “a legend.”

Morrill retired in 2019 as consulting director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, but he wasn’t really ready to retire. “I’m not a good spectator. I like to have an impact,” he says. “I’m a good pioneer. I’m not a good settler.” After 46 years with the Historic Landmarks Commission, a county government agency, he wanted to approach historic preservation from the private sector in what he calls a “real estate, business-savvy group.”

He and longtime friend Frank Bragg (’61, P ’88, ’90, ’93) founded Preserve Mecklenburg Inc., a nonprofit that preserves properties of historical and cultural significance in Mecklenburg and surrounding counties. PMI purchases and resells, or buys options to purchase, threatened properties, then places preservation easements or deed covenants to protect a historic house or other structure on the property forever.

Dan Morrill ('60) at his own house in Charlotte.

Starting PMI probably wouldn’t have worked with anyone besides Morrill leading the efforts, says Bragg, who served on the Historic Landmarks Commission for seven years. “Dan is so knowledgable, and he’s known around the state by historic preservation people,” he says. “And he’s a great storyteller.”

Bragg is founder and chairman emeritus of Bragg Financial Advisors in Charlotte and a past chair of the Catawba Lands Conservancy. “The average person thinks that Charlotte tears down everything. But there’s more (historic properties) left than what people think,” Bragg says. “We’re working as hard as we can to save what’s left.”

Morrill says a community needs a strong public preservation program and a strong private one. Jack W.L. Thomson, executive director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, says the programs complement one another. Thomson worked in private preservation organizations in Asheville and Salisbury before succeeding Morrill.

Private nonprofits can move quicker, take more risks and be more creative than a government agency. “A community needs multiple layers of preservation initiatives,” Thomson said. “With the agility of a private nonprofit, they can act more swiftly to protect property through private agreements and covenants.”

PMI is involved with about a dozen projects besides the Akers house, including Edgewood Farm, an 1850s plantation house; Cedar Grove, an 1830s Greek Revival home; the J. Wilson Alexander tenant house, an African American tenant house, one of the last remaining in Mecklenburg County; and a 1925 narrow wooden building that once housed the Patterson-Logan grocery store that served an African American neighborhood, one of the last of its type in Charlotte.

Morrill brings a historian’s love of the stories behind historic properties and a practical approach to bring together homeowners, developers and historic preservation experts. He’s not trying to prevent change; he’s trying to manage it so that inevitable new development and historic properties can co-exist.

James Jones Akers and Nancy Anderson Akers house in Charlotte, completed in 1937.

Morrill can recite the Akers house’s history in detail, befitting the history professor that he was at UNC Charlotte. “It’s the stories that make the houses worth saving,” he says. He retired in 2014 after 51 years as a professor at UNCC, the longest tenured faculty member ever at the school.

But perhaps surprisingly, given his passion for historic preservation, he didn’t teach architecture or historic preservation or even American history. He taught Russian history, the hot field for aspiring young Ph.D. students when he graduated from Wake Forest and into the Cold War era. He earned a Ph.D. in Russian history at Emory and found a job teaching at what was then Charlotte College.

He doesn’t find that Russian history angle that interesting. After all, he grew up in Winston-Salem, with its rich Moravian history, he points out. His father, who worked at a Firestone tire store across from the old Robert E. Lee Hotel in downtown Winston-Salem, took him to Old Salem and Bethabara. His father loved military history; his mother loved old buildings and antique furniture. His mother took him to Old Salem’s God’s Acre cemetery to clean off relatives’ gravestones before the annual Easter sunrise service. “That kind of thing just gets in your bones,” he says.

As a teenager, he visited Reynolda House — when it was still the family home of Charles (LL.D. ’58) and Mary Reynolds Babcock and their four children, and not an art museum — to see a girlfriend who babysat for the family. He remembers driving onto what had been the Reynolds’ farm and pastures and watching Wake Forest’s new campus taking shape. “I was fascinated with seeing it come to life. I’m a big believer in the built environment, the man-made environment. How spaces and places are arranged is very important in terms of building a sense of meaning and character.”

After his freshman year at Davidson College, he transferred to Wake Forest. A trio of professors influenced his future path. There was classical languages professor Carl Harris (’44), “a wonderfully nurturing, kind man and wonderful teacher.” History professor Percival Perry (’37, P ’80) taught him more Winston-Salem history. History professor Lowell Tillett (P ’76, ’78) introduced him to Russian history. “I’m not saying that this was done explicitly, but it was certainly done implicitly, that one of the things Wake Forest communicated to me was you need to try to make a difference,” he says.

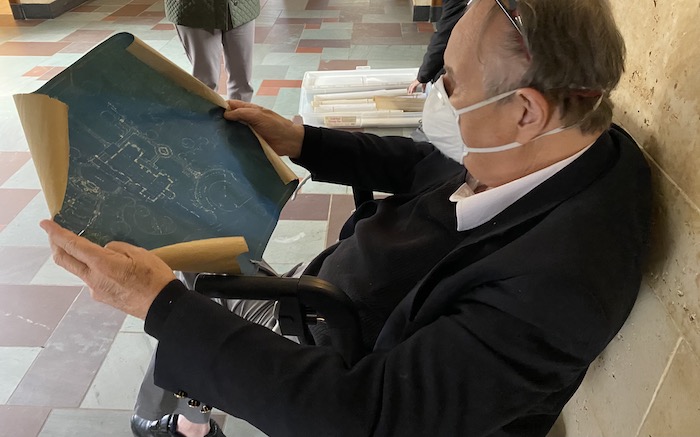

Dan Morrill ('60) reviews a site plan for the James Jones Akers and Nancy Anderson Akers house in Charlotte.

When he joined the faculty at UNCC, he might have been content to devote all his time to Russian history if the clutch on his ’73 Ford Mustang hadn’t gone bad. He had become somewhat well known in local preservation circles after he and a colleague won a grant from the North Carolina Humanities Council to advocate for historic preservation in Charlotte. “We’d go up to the skyscrapers uptown and talk about it. You talk about Jesus going into the saloon,” is how he puts it. “Charlotte’s identity comes from what it aspires to be, not where it’s been.”

It was about this time that Charlotte was starting a historic properties commission and searching for a consulting director. There wasn’t much need for a Russian-history consultant in Charlotte, so Morrill saw a chance to make a difference in preservation. It didn’t pay much but “it was enough to get my clutch fixed,” Morrill says of accepting the position in 1974, and he became immersed in Charlotte history. “It was Percival Perry on steroids. Percival always said, ‘You need to focus on your local community. You need to know where you live.’ I had all the research and writing skills, so I started building the program.”

During his 46 years as consulting director, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, with the support of local government, secured the designation of more than 300 local historic landmarks.

“Dan is well known in the preservation community across the state for the success that he had with the Historic Landmarks Commission,” says Thomson, who succeeded him. “His work resulted in the largest inventory of designated local landmarks of any county in the state. And he helped establish a revolving fund, capitalized at over $4 million (today), held by Mecklenburg County, that can be used by the landmarks commission to acquire historic landmarks.”

The early 1830s Greek Revival style James G. Torrance house, also called Cedar Grove, in Huntersville, North Carolina, is being preserved by Preserve Mecklenburg.

There’s more to Charlotte’s history than you might think, Morrill says, especially in its early 20th-century neighborhoods. That’s what brought him, Bragg and Springsteed on a February afternoon to the Akers house, set in a clearing of trees about 50 yards off busy Sardis Road.

The country estate of James Akers, an insurance company executive, and his wife, Nancy, was designed by architect Louis Asbury Sr. Asbury built several other early 20th-century structures in Charlotte including the old Mecklenburg County Courthouse, Myers Park United Methodist Church and the First National Bank building, the tallest building in the Carolinas when it was completed in 1927.

“Charlotte doesn’t have many houses like this,” says Springsteed, who’s marketing the 7,800-square-foot house and 6 acres for $4.95 million. “To save one, it’s worth the effort, and I believe we’ve got it done.”

The homeowners had already turned down offers from several developers who planned to tear the house down before turning to PMI. PMI paid the homeowners a $1 option to purchase the house for a specified time period, which gave it time to come up with a plan. Once Springsteed sells the property, PMI will assign its option to the buyer, with a preservation easement attached, but infill redevelopment will be allowed on the edges of the property. (As of Feb. 22, an offer was pending on the property.)

The preservation easement, or a deed restriction, prevents a historic structure from ever being torn down. It’s more protection than offered by the National Register of Historic Places or being listed as a local historical landmark, which can delay, but not prevent a house from being torn down. (The Akers house is not on any historic registry, but is certainly worthy, Morrill says, and PMI will work with the new owners if they pursue that.)

About 15 minutes away from the Akers house, Morrill points to another success for PMI, the 1928 Colonial Revival Knowlton-Shaw house, near the Charlotte Country Club. The house was built by Duke Power engineer James Knowlton. Charlotte mayor Victor Shaw, who pushed for construction of the original Charlotte Coliseum and Owens Auditorium, and his family lived there during his two terms in office in the 1940s and 1950s.

1928 Colonial Revival Knowlton-Shaw house, near the Charlotte Country Club.

The property was going to be redeveloped because of its valuable location, Morrill says. The only question was whether the house could be saved. PMI bought an option to purchase the property, then found a developer willing to accept a preservation easement to preserve the house, while being allowed to redevelop the rest of the property. The developer is already building new cottages beside and behind the historic house.

“People say you either save it or you destroy it. That’s not necessarily true. There are other options, but you have to be creative,” Morrill says. “The owner got his money, the developer will get their money and the house is preserved for perpetuity. Everybody wins.”

Preservation doesn’t have to be an “all or nothing” strategy, he says. “I’m a realist, not an idealist. Preservation is real estate. If the numbers don’t work, you’re not going to save anything.”

PMI’s list of projects covers a wider view of the community’s history — from grand manor houses to a tenant house and an African American grocery store — than would have been normal when Morrill first started in the field. Preservation was all about saving “Old South, pre-Civil War” properties then, he says. Now, “there is a lot more interest in the African American community and a growing sense of the importance of (their) heritage. Preservationists are more attentive to include a broader range (of properties) than they were in the 1970s.”

For someone who’s spent the better part of his life preserving the past, with no plans to stop, he says historic preservation isn’t really about the past. “A lot of people think that. That’s a big mistake. Preservation is about the future and creating a sense of cultural continuity in the built environment,” he says. “You never win in historic preservation; it’s a never-ending battle to save what you can.”

The Patterson-Logan grocery store that served an African American neighborhood, one of the last of its type in Charlotte, is being preserved by Preserve Mecklenburg.