Following the death of Apple co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs in 2011, COO-turned-CEO Tim Cook and chief design officer Jony Ive, who created the iMac, iPad and iPhone, battled over the company’s future.

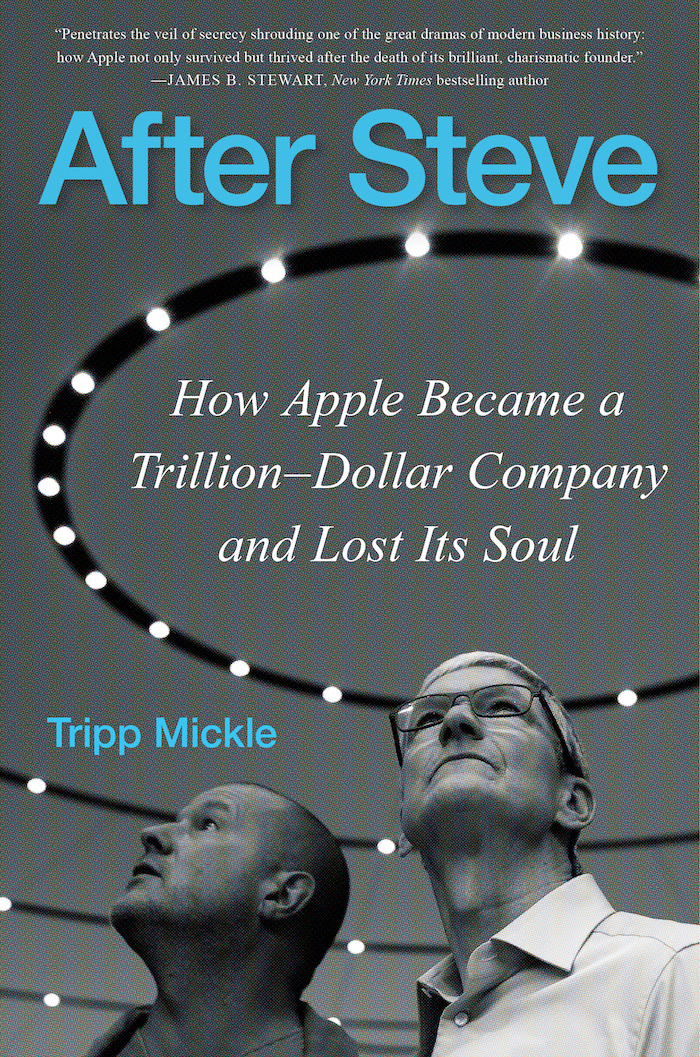

In a new book, “After Steve: How Apple Become a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul (William Morrow),” Tripp Mickle (’03) reveals how the rise of Cook and the decline and eventual departure of Ive led to Apple’s focus on expanding services rather than designing innovative products. “The creative soul of Apple had been eclipsed by the machine,” Mickle writes. “Without Jobs, some thought, Apple had become a machine with a heart of stone. … (O)ver time, the company’s bureaucratic caboose had become its engine.”

Mickle, 41, is a technology reporter for The New York Times. He previously wrote about Apple, Google and other Silicon Valley giants at The Wall Street Journal. He and his wife live in San Francisco. His parents, Russ Mickle Jr. (’72) and Marilynn Strowd Mickle (’74), and sister and brother-in-law, Jennifer Mickle Cooper (MD ’10) and Joshua Cooper (MD ’11), are also alumni.

“After Steve”: Reviewed by The New York Times and Business Insider

Let me start at the end of the book. In the acknowledgments, you mention Justin Catanoso (MALS ’93), professor of the practice in journalism.

He’s become a great, great friend.…a professor who had a profound influence on my life who I’ve stayed in touch with for two decades He opened my eyes to the things in journalism that I would’ve never come across otherwise. He gave me my first opportunity to be a business writer and intern at the Triad Business Journal. He’s been a big advocate and supporter as I’ve pursued my career. On this book, I reached out to him early as I was trying to figure out how to proceed. He spent a lot of time talking to me about structure and helped me think through some of the structural things that I would eventually have to tackle as I built the book out.

You interviewed more than 200 current and former Apple employees to provide a rich level of detail to help the reader understand Tim Cook and Jony Ive and what was happening inside Apple following Steve Jobs’ death. How did you get so many people to talk to you despite Apple’s penchant for secrecy?

Because it was a book, it lent itself to approaching someone and saying, “Look, this is an important moment in corporate history. Seldom do you see a company that’s lost or had a co-founder die. How you navigated that is really an important part of our understanding of the business world.” And asking people to see the value of sharing their story. Many times people said no, but the luxury of a book is you can come back to people later. You have the privilege of time. I was able to come back to people and say, “Hey, I’ve made this much headway. You could help me here.” And, with time you’re able to accumulate the details. Those make the story come alive for the reader and create these two figures (Tim Cook and Jony Ive) as foils to each other in a way that makes them resonate.

Did you interview Cook and Ive?

I can’t really go into all the sourcing on the book. I had to seek the perspective of people around them and court the feedback of their representatives so that I made sure that the book was accurate and a true representation of the events that it portrays.

Can you set the stage for what was happening right before Steve Jobs’ death in 2011, which is when your book begins?

He knew that he’s going to die. He’s extremely concerned that the product that he cares about most in the world survives and carries on. And the product he cared most about was Apple itself. He began obsessively looking at other companies that lost important founders to try to figure out what mistakes they made. The three that he focused on, as the book covers, are Sony, Polaroid and Disney. All three of those companies floundered after their founder died.

He sought to set Apple up in a position to avoid that. He empowered two figures to carry on the work – Jony Ive, who was focused on the product side of Apple and who Steve Jobs said was the second most important person at the company after Jobs himself. And Tim Cook, who took the products that Jony Ive and Steve Jobs dreamed up and made them a reality by having them manufactured, in China primarily. He empowered them to lead the company. Meanwhile, the outside world is looking at what’s happening at Apple and says, “There’s just no way this company is going to survive without him.”

Tripp Mickle ('03) is a technology reporter for The New York Times and the author of "After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul."

I thought one sentence in the book really summed up Apple’s inexorable shift the last 10 years to focus on lucrative services rather than innovative products. “After years of being hounded by the same question – What’s the next new device? – Cook had finally delivered his answer: There isn’t one.”

Apple reached a point where the demands and expectations of Wall Street were so great because it had become the world’s largest company. It continues to hold onto that perch, which is unusual. The pressure from Wall Street to deliver growth was unrelenting. Tim Cook ultimately looked at what they had already available at their disposal without having to create something totally new and embarked on the strategy of releasing subscription services, like Apple Music and TV. The products were new, but they were on the back of the iPhone that fueled so much of the company’s growth years earlier. And that strategy is ultimately his greatest conquest. It’s what unlocked a lot of shareholder value for investors in Apple.

Was it inevitable that Apple would go down this road, or, and I know this is impossible to really know, would Jobs have pushed Apple’s innovation to the next level, as he had before?

A lot of people who were close to him think that the company probably would not have been as successful over this decade under Steve Jobs as it was under Tim Cook. The challenges that it was facing had less to do with making and releasing new products and more to do with navigating tricky political issues, like Donald Trump waging a trade battle in China and Apple being caught in the middle. In many ways, Steve Jobs disdained politics. He famously refused to dine with President Obama until his wife persisted and drove him to do it. Tim Cook embraced that aspect of his role, which was important because Apple, by that point, had become an empire, a borderless country almost. Tim Cook sits at the table with Donald Trump and (China’s) Xi Jinping and influences actions across the world, because Apple’s such a big piece of the stock market.

“Without Jobs, some thought, Apple had become a machine with a heart of stone. … (O)ver time, the company’s bureaucratic caboose had become its engine.”

Your book isn’t so much about technology as the human drama that unfolds as Ive tries, and fails, to replicate Apple’s past by creating the next great product, and Cook moves in an entirely different direction. Like any good novel, you have a hero, Ive, and a villain, Cook. I don’t know if that was your intent, but I found myself rooting for Jony Ive.

I think that’s a fair read, but I’ve also heard people read it the opposite (way). Jony Ive grows disillusioned with the company, goes part-time and hangs out with more and more celebrities. He’s less involved in making sure that the business is running the way it should. Jony Ive became a bit of a villain in their eyes, and Tim Cook became the hero. He (Cook) was steering the ship and being the responsible executive.

I think that (the different conclusions) speaks to the fact that each of these figures are uber examples of our right brain and our left brain. Each of us has some creative inclination; Jony Ive is the uber example of the uber creative. Tim Cook is the uber example of the numbers guy. I think there are a lot of reasons to find sympathy with Jony Ive and his artistic sensibilities and feeling like he landed in a world that he no longer recognized.

Which is kind of sad.

Right. When Jony Ive first left the company and I was writing about this, I thought about David Byrne and the Talking Heads song, “Once in a Lifetime.” This is not my beautiful house. This is not my beautiful wife. Where am I, what have I done? And that just seemed to be a point that he arrived at shortly before leaving the company.

So which side do you come down on?

I’m sympathetic to Jony. I’m a writer, and I’m sympathetic to the idea that he relied on an editor, Steve Jobs, to make sure he was designing the best products he possibly could. He went through a period of grief (after Jobs’ death), and worked really hard, got burned out and left. It’s hard not to look back at the arc of his story and not be sympathetic to it. But you have to have adults in the room, and Tim Cook is the adult in the room. Just because the adult in the room tells you, “Don’t pour your water on the floor” doesn’t mean that they’re not a sympathetic figure or that they’re not doing the right thing.

And it’s hard to argue with Cook’s success, isn’t it?

Absolutely. He’s the most successful successor that you see. That’s just rare. I like to think of it in sports analogies, like (legendary Alabama football coach) Bear Bryant and how long it took to find Nick Saban for Alabama to have success again. That’s more what you see in the world of succession, when you go from a great leader to whoever may come next. In Steve Jobs’ case, it’s hard to argue with the achievements of Tim Cook.

"The presentation ... depicted a future in which Ive – and the company's business as a product maker – would matter less and Cook's increasing emphasis on services – such as Apple Music and iCloud – would matter more."

You mentioned earlier Steve Jobs’ obsession with a succession plan. What lessons are there in what happened at Apple for other businesses, particularly those who have iconic dominating founders?

In tapping Tim Cook, Steve Jobs recognized the one thing that was going to be most important to Apple’s longevity in the near term. And I would say near term being the first, roughly, five years after his death. And that was going to be the expansion of the iPhone. At the time of his death, Apple was selling about 20 million iPhones a year. They now sell about 200 million. And if he tapped the wrong person, i.e., somebody who didn’t appreciate how important it was to efficiently make those products and make 200 million of them perfectly, Apple wouldn’t be as successful today as it is. He rightly recognized that Tim Cook was the person to lead the company forward because he knew that aspect of the business best.

You’ve covered Apple for years, but what did you learn writing the book that surprised you the most?

I’m going to answer this twofold. One on Tim Cook and one on Jony Ive. As a Southerner who came into this curious about how somebody from the South wound up leading a California company that is the most influential and successful in the world, I was curious about how Tim got there. I went to his hometown (Robertsdale, Alabama) expecting that people would be proud of his story. Instead, they don’t have a lot of love for Tim Cook, and that surprised me.

Around 2013, 2014, he gave a speech about seeing a cross burning in his hometown. A lot of people in town question whether that story was true. More than that, they didn’t appreciate that it put the town in a bad light. Even close friends questioned and challenged him. I just didn’t anticipate that. I think it speaks to the lingering frictions and tensions in the Southeast and race-related matters and our collective effort to make peace with things from the past.

Did their feelings about Cook have anything to do with him being gay?

I wondered that, too. I left unpersuaded that was the issue there. That being said, it was the ’70s in Alabama (when Cook was growing up there). It was not an easy time to be different, as Cook said he was at that time. But I didn’t leave with the impression in talking to people locally that their issues or qualms with Tim Cook were because he’s gay. I left with the distinct impression that it had everything to do with the fact that he said there was a cross burning and racial tensions in the town.

And what surprised you about Ive?

I found it really interesting that people around him question whether he has X-ray vision or an ability to see the world in a way that the rest of us can’t. There’s just some great anecdotes. One of my favorite ones, after working several days on the factory floor in China, he goes to the airport to fly home. He’s sitting at a bar that’s silver and about 30 feet long. He looks at it and turns to the guy to the side of him and says, “I can see every seam in this bar.” The guy looks at the bar and is mystified because to him it just looks like smooth metal. He looks at him (Ive) and says, “Your life must be miserable.” People joke that he could, quote, see dead people, because he almost had a sixth sense that others don’t have. I found it really fascinating that people think he saw the world differently from the rest of us.

Cook delivered "one of the most lucrative business successions in history by squeezing more sales out of the business he had inherited. ... Whereas Jobs had given Apple its identify by orchestrating leaps and upending industries, Cook focused on preserving the product he considered to be Jobs's greatest: Apple itself."

You also write about Apple’s spaceship-like headquarters, Apple Park, designed by Ive, that opened in 2017.

It’s beautiful. It’s breathtaking. The image that stays with me is this monstrous cafeteria. It’s so big that they have trees, literally trees, inside the cafeteria. I remember sitting at a table (looking at) a walkway against a full glass wall that looks back onto the interior of the campus. People are walking across this walkway with the sun behind them, so they were backlit. And they looked exactly like the silhouette from the iPod commercial. They’re just these dark figures. They looked like they were walking on air. That’s the moment I was like, “Wow. They really did build something truly special.” The book goes into a lot of the (building’s) flaws and the moving pains of inhabiting that space. But it’s still a modern marvel when it comes to architecture.

Are Apple’s best days, in terms of innovation, behind it?

Apple has the power within itself to still be innovative, but it needs to have an individual come forward, based on the way the company’s designed, who can lead and spur that innovation. I think that’s the open question in Jony Ive’s (creative) department. He was the last individual to really drive a new product category for the company, the watch and AirPods. It’s an open question as to who fills that void.

What is Apple working on now?

The two projects that are most anticipated and reported on right now are AR glasses and goggles, which could come sometime in the next few years. And then the other is a car which is anticipated in 2025 or later. They’ve really struggled with those projects. Both require huge technological leaps. The glasses, because it’s a relatively small form factor, and you need to have battery power for it and then not overheat because it’s near your head. On the car, the challenge is that they want it to have some sophisticated autonomous capabilities, more so than even Tesla has. And that takes a lot of software refinement and development, and they haven’t cleared those hurdles yet.