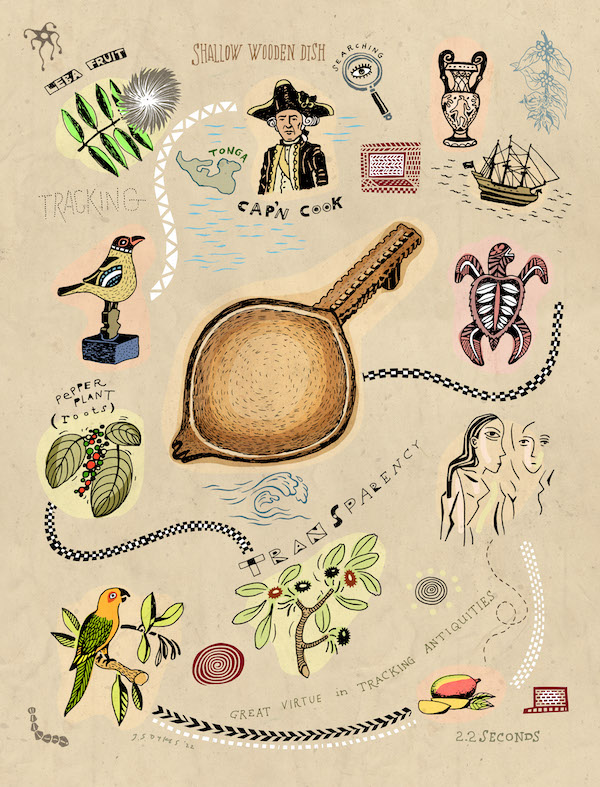

In the mid-1700s, an artist on an unknown island in Fiji intricately carves a piece of wood into a shallow dish, the shape inspired by a tropical leba fruit, or perhaps a bird. The bete, or priests, of Fiji have commissioned the bowl for mixing coconut oil, fruit and pigments into their favored body oils, colorful and perfumed.

At 13 inches long, it is one of many wooden containers serving the powerful priests in the South Pacific archipelago. Using their larger, deeper wooden bowls, the bete concoct an earthy liquid of water and grated pepper plant roots. They drink this potion in sacred rituals to induce a trance state, inviting ancestral spirits to enter their bodies and channel visions and wisdom for the chiefs and their tribes.

What if the bete could have envisioned the destiny of their humble shallow dish? They would see it cross seas in the hands of a legendary explorer and centuries in collections of curiosities and art, eventually to rest under glass in the Timothy S. Y. Lam Museum of Anthropology at Wake Forest. The dish would acquire title as the oldest known historical wooden object in existence from Fiji, with a history that includes obsessed collectors and a connection to a kidnapping.

TODAY, steered by Wake Foresters and a New York City arts leader, the dish has gone even farther without moving an inch, as a piece of the inspiration for a Wake Forest novel experiment that will cross invisible realms, through space and time, in 21st-century cyberspace.

Susan de Menil (P ‘19)

Susan de Menil (P ’19), a design consultant and cultural heritage thinker, is leading the project, driven by innovative blockchain technology and an equally innovative interdisciplinary Wake Forest group.

Two law students and a physics major formed the core for the group’s radical collaboration, which spans anthropology, computer science, art, law and business. They are creating a white paper laying out the case for a first-of-its-kind tool they envision for museums, dealers and others to track treasures of antiquity.

The goal is to equip guardians and purveyors of art and cultural objects with a blueprint that could create new ways of managing intractable issues of practice and ethics. The envisioned tool will address how to share ownership of objects, often with histories as complex as that of the Fiji dish, across disparate cultures and vast expanses of time.

The three students, all now alumni, are developing a plan for a prototype with programs based on blockchain technology — heralded and notorious for its use in cryptocurrency, often mysterious to laypeople, yet holding a mother lode of possibilities beyond Bitcoin. A blockchain is a unique type of database with advanced security features. “Blocks” containing data are “chained” together. Users can add but not delete anything.

Wake Forest’s blockchain and cultural property project is deeply collaborative around a technology topic difficult for many to comprehend, says Provost Rogan Kersh (’86), whose office oversees the project. “It’s radical because it involves such widespread, non-obvious, almost unnatural disciplinary collaborations,” he says. “They’ve come together to do something really, really useful in a space that nobody understands. I just cannot think of a more fruitful example of radical collaboration in an academic setting.”

Raina Haque, a professor of practice of technology in the School of Law and a key leader in the group, says, “What’s exciting about our project is we’re really juxtaposing something ancient with something that’s cutting edge, and then seeing how we can bridge the two.”

A FORTUNATE CONNECTION

The Wake Forest project sprouted from a casual question in August 2019 as Kersh had lunch in New York with de Menil, whose son Conrad (’19) graduated that year.

“What are you working on?” Kersh asked her.

“I’m actually into the strangest space — art and antiquities in the blockchain,” she told him.

Only the blockchain aspect was strange for de Menil. For more than 30 years, with her husband, architect François de Menil (P ’19), she has been active in the arts and museum world. A 1986 story in The New York Times about the de Menil family and their Houston art museum was headlined, “The Medici of Modern Art,” referring to the patrons who fueled the Italian Renaissance.

The matriarch, Dominique de Menil, was a visionary force with her husband, John. She had a keen eye for artwork and an equal ability to spot illegally acquired objects long before equity and social justice were named as ethical values in American society.

In 1983, Dominique de Menil rescued what she suspected were valuable, sacred pieces of Byzantine frescoes pitched to her by shady characters in a dimly lit room in Germany. The experienced art collector immediately sent out letters and determined eventually that the frescoes originated in Lysi, Cyprus, at a small monastic Greek Orthodox Church looted after Turkish occupation in 1974.

She established a foundation that bought the frescoes and restored them, costing millions. François de Menil designed the Byzantine Fresco Chapel in Houston to display them in the family’s Menil Collection, which includes the Rothko Chapel named for Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko.

Interior of the Byzantine Fresco Chapel when it held the 13th-century restored treasures on loan until they were returned to Cyprus in 2012. To see a 10-minute video of the complex de-installation of the frescos, search "Byzantine Chapel Fresco De-installation" on youtube.com. Photo by Paul Warchol, Courtesy of Menil archives, The Menil Collection, Houston

When Dominique died in 1997, the museum’s board asked Susan de Menil to serve as president and lead the complex negotiations on whether and how Cyprus would reclaim the frescoes, as her mother-in-law had agreed. More than 450,000 people visited the Byzantine Fresco Chapel in Houston, “probably more than all the people who had seen them since the 13th century,” Susan de Menil says. The frescoes returned in 2012 to their native country.

In the last few years, de Menil became inspired by the new social justice conversations and museums’ awareness of the need to acknowledge and share equity with the cultures where ancient objects originated. She saw museums and auction houses unwilling to sell, acquire or accept treasures whose transactional history — known as their provenance — could not be confirmed as legal or ethical. This made it hard for families to donate treasures.

“Every time (an auction house) would take a consignment, it would get questioned,” de Menil says, “so it became a losing economic reality for them. … Suddenly you had all these so-called orphaned objects all over the world. That seemed like that’s not really serving anybody terribly well.”

De Menil learned about blockchain from a friend, previously at Christie’s auction house, who had seen it used for a buyer. De Menil, her friend and a handful of other women prominent in law, academia and business in New York began gathering regularly to talk about the possibilities. They formed the Arts & Antiquities Blockchain Consortium (AABC).

After the lunch in New York, Kersh connected de Menil with the law school’s Raina Haque, who has deep knowledge of blockchain. They met in the fall of 2019, and the brainstorming began.

The group expanded to include Christina Soriano, the associate provost for arts and interdisciplinary initiatives, along with professors of art, computer science and business. Andrew Gurstelle, the anthropology museum’s academic director, rounded out the dynamic group, bringing with him the background of the Fiji dish as one of the touchstones for the project.

CAPT. COOK AND THE FIJI DISH

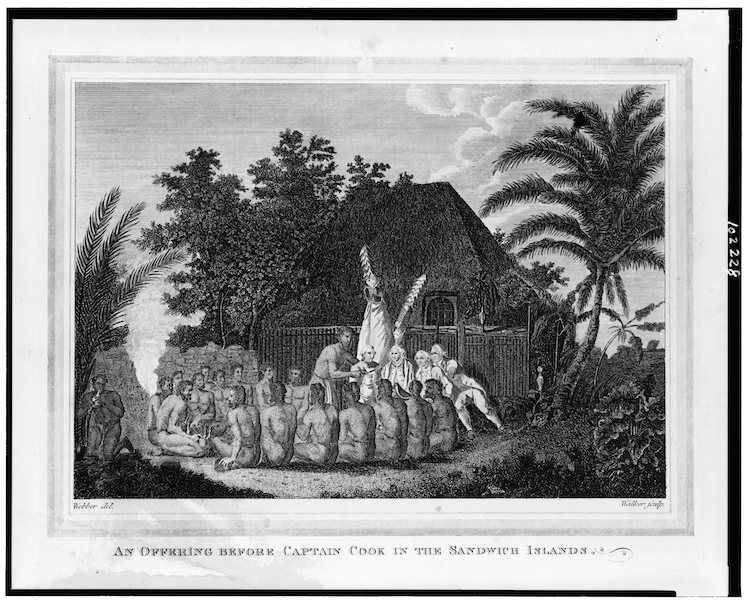

Fiji first came literally onto the horizon of British explorer Capt. James Cook in 1774 as he made his second of three voyages ‘round the world. The fabulous success of his first voyage had earned him renown and a major upgrade from his first ship, HMS Endeavour, a Navy research vessel known as a bark, faster and lighter than a full-rigged ship and often favored by pirates.

For his second voyage circumnavigating the icy waters of Antarctica, Cook needed a stouter ship. The British Navy royally outfitted the 14-month-old HMS Resolution with “the most advanced navigational aids of the day, including … ice anchors and the latest apparatus for distilling fresh water from sea water,” says the Captain Cook Society.

Cook called her “the ship of my choice, the fittest for service of any I have ever seen.”

Fiji did not manage to impress the great captain nearly so much.

On July 2, 1774, his men spotted land and hurried toward Vatoa, a southeastern islet among more than 300 islands in Fiji’s archipelago. But it proved to be “an Island of so little consequence,” Cook’s journal says, that he landed only briefly and encountered no residents.

How, then, did Cook acquire the Fiji bowl?

Gurstelle at the anthropology museum and his father, Bill Gurstelle, who is pursuing his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota, spent nine months researching the bowl’s past. Andrew Gurstelle says the most logical conclusion is that Tongans gifted the bowl to Cook, or he received it from Fijian traders staying on Tonga, a more appealing island that Cook called the “Friendly Archipelago.” South Pacific islanders practiced diplomacy by bestowing many gifts on the Europeans, Gurstelle says. Cook gathered plants, animal specimens, delicate earrings of shells or pearls, woven bark cloth and other exotic treasures.

WHAT IS BLOCKCHAIN, ANYWAY?

Exotic might be a fair way to describe how some modern citizens view blockchain technology. Mention it or its eponymous companions — cryptocurrency, Bitcoin and NFTs (digital “non-fungible tokens” of ownership) — and a furrowed brow or a grimace often follows. But those who follow technology see blockchain holding a permanent place in the future, and de Menil saw its potential for connecting that future to tracking artifacts of the past such as the Fiji dish.

How cryptocurrency works as an economic exchange is much harder to understand than the core concepts of blockchain technology itself.

Will Caulkins (’22) came into the Wake Forest project as a physics major eager to expand his expertise in his computer science and math minors. He has learned how to program using a well-publicized global blockchain and functions as the team’s programmer.

Blockchain’s secure ledger function is key. “If something is tampered with in your previous transaction, … you can easily recognize if something has been entered,” Caulkins says, making it “an environment that is the most secure on the planet.”

That transparency is a great virtue in tracking antiquities, whose analog documentation has always been subject to forgery, fiction or the fragility of a paper trail — or no trail at all.

“What’s exciting about our project is we’re really juxtaposing something ancient with something that’s cutting edge, and then seeing how we can bridge the two.”

–Raina Haque, professor of practice of technology in the School of Law

The second crucial aspect of blockchain is its decentralized network, with all users giving up a little part of their network’s memory rather than one entity controlling the database.

“A bad actor wanting to take over the blockchain or alter something, they would have to surpass the computing power of (a majority of) everyone in the blockchain, which is an enormous (number of) people. Basically, you can’t tamper with it at all, and it exists forever,” Caulkins says.

Programming on a blockchain requires no massive computer power.

“It’s really cool because you don’t have to have this huge data center with lots of security protocols and all that,” Caulkins says.

This is especially useful for museums and smaller institutions without big budgets.

While programming on a blockchain isn’t itself energy intensive, some cryptocurrency companies are in the news for heavy energy use in their security features. Facing criticism, many are working on ways to reduce consumption.

Gurstelle notes that the tool envisioned by the Wake Forest team can’t eliminate the need to verify historical provenance, but once a piece of an item’s history is verified, the documentation going forward will be more useful and trustworthy.

INFINITE POSSIBILITIES PAST THE CHALLENGES

Blockchain carries the potential to track items directly from archaeological digs, to open avenues for diplomacy and negotiation and to share exhibit revenues and ownership, de Menil’s New York consortium wrote in the International Journal of Cultural Policy in 2020.

For example, Gurstelle says, a museum could divide ownership of a collection among 5,000 individuals from the region where the items originated. Each person would get a USB thumb drive documenting the person’s or family’s ownership. “They can sell (their shares) to someone else. They could acquire other shares. They could subdivide that further and give their children equal shares,” he says.

The nonprofit Wake Forest museum continues to research the provenance of various objects, and Gurstelle has reached out to officials in other countries to determine appropriate and ethical ways to honor objects’ source cultures.

As Walmart developed a blockchain system, the company used mangoes in a contamination scenario. Normal tracking took a week to find the culprit. Blockchain identified the source in 2.2 seconds.

The tracking prowess of blockchain is an important issue across society, beyond the art and museum worlds, says law professor Haque.

Consider that Walmart has been moving its food suppliers to blockchain, she notes. Both Walmart and farmers had lost millions as the company froze purchases to investigate the source of E. coli contamination, for example. As Walmart developed a blockchain system, the company used mangoes in a contamination scenario. Normal tracking took a week to find the culprit. Blockchain identified the source in 2.2 seconds.

Cryptocurrency, susceptible to misinformation and scams, is fogging the visions for blockchain innovation, says Haque. The law and regulators — generally slow to change — are just figuring out that this uncharted virtual economy will need new thinking, she says. They will need critical minds with fresh perspectives like those of her law students, she says.

“Blockchain technologies are so hyped up, and most of the articulated cases I’ve seen for implementing a blockchain really just don’t make sense. They’re riding the hype to get investment money,” says Haque.

The Wake Forest project, however, “really struck me because it made so much sense because we’re talking about a need for efficient transactions across borders … and cultural diasporas.”

FROM CAPT. COOK TO THE HOLOPHUSICON

The Fiji dish might never have made it out of the South Pacific but for a moment of fate. As Cook prepared to depart the “Friendly Archipelago” of Tonga, a Tongan chief was plotting to assassinate him. Thanks to a change in Cook’s timing and infighting among the chiefs, the plot failed.

Upon Cook’s return to London in 1775, he gave many items to his friend Ashton Lever, whose family’s fabulous wealth in textiles freed Lever to pursue his passions of archery and collecting cultural objects. Cook “so much admired this good Ashton’s intellect, that he gave him a complete collection of all kinds of South Seas curiosities,” a visitor wrote at the time, according to the Gurstelles’ research. Lever acquired the Fiji dish in that 1775 gift or possibly from Cook’s wife when the HMS Resolution returned with more bounty after Cook’s death in 1779.

The dish probably survived because of its relatively swift arrival in London within a year or so of Cook’s acquisition, Gurstelle says. Museums have stone artifacts from Fiji that have survived many thousands of years, but wooden objects generally decayed in the Polynesian humidity. That’s why Gurstelle estimates the dish’s creation at 250 years ago. He hasn’t found references to any older wooden objects from Fiji.

“We know that museums really were invented by showmen like Barnum, and … while museums have a more serious focus today, our role is still to give people a sense of wonder at the world.”

– Andrew Gurstelle

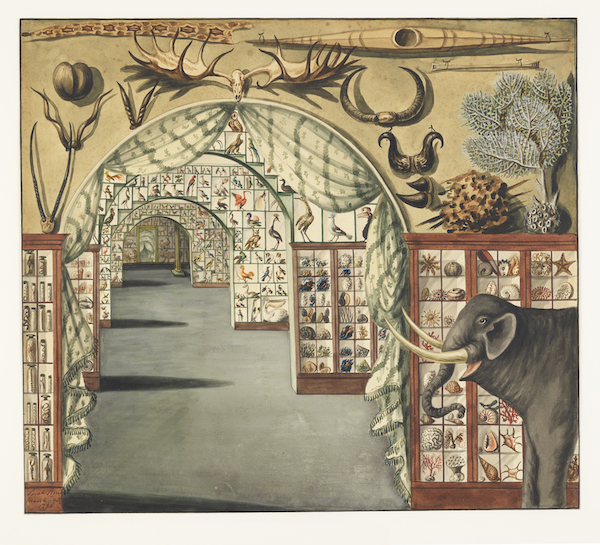

Lever displayed the dish in the somewhat protected environs of his museum, named the Holophusicon (HO luh FOO suh kahn) — “the place that embraces all of nature.”

Visitors flocked to see Capt. Cook’s riches and thousands of scientific, historical and ethnographic objects and taxidermied animals that Lever had amassed since 1760.

“This was the Disneyland of its time period,” Gurstelle says. “It was intended to be an overwhelming sensory experience.”

Gurstelle understands why exotic cultures and species awed the British people. The unusual fascinates him, too, as does stoking the public’s curiosity. He talked his way at 14 into his first job as a carnival barker. As a teen working in a juggling shop, he earned a scar on his palm when a little boy tugged at Gurstelle’s shirt and distracted him as he juggled machetes.

Andrew Gurstelle with the Fiji dish

“We know that museums really were invented by showmen like Barnum, and … while museums have a more serious focus today, our role is still to give people a sense of wonder at the world,” he says.

The Holophusicon grew into the largest private museum in the world. But by 1786 its operating expenses exceeded revenues.

The Fiji dish was soon evicted.

CREATING A BLOCKCHAIN HACKATHON

De Menil saw value in the new perspective of young people to grapple with the larger cultural questions around treasures. She and the Wake Forest professors began discussing how to incorporate blockchain and antiquities into WakeHacks 2021, the annual hackathon by the student computer science club and the Department of Computer Science. Student teams compete in 24 hours of nonstop planning and programming to propose solutions to a problem presented to them.

Contributing to the yearlong work to prepare for the hackathon were Haque, de Menil, Soriano, Gurstelle, Assistant Professor of Computer Science Sarra Alqahtani and Professor of Art History Morna O’Neill, as well as the Arts & Antiquities Blockchain Consortium. Students could take courses on blockchain in law, computer science, anthropology or art.

De Menil wanted real items to give meaning to the challenges students faced and to spark their creativity. Gurstelle had already begun researching the Fiji dish for an introductory class on museum studies. Besides enlisting his father in the time-consuming online research, Gurstelle had help from Z. Smith Reynolds Library, the Smithsonian and the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

The dish turned out to have a very long, complicated journey that well illustrates the challenges of building a verified provenance, de Menil says.

“The dish … was very inspirational because it was a real, live cultural artifact,” de Menil says. “It encompassed so much of the underlying issues and thoughts that everybody was trying to explore. The fact that it had been in so many different places over time, the whole travel in the life of that object became kind of an anthem on a certain level for the whole project.”

For the March 2021 hackathon, students could choose their challenge from three scenarios involving museum objects — the Fiji dish, a ceramic bowl from Mexico and a funerary statue from Niger.

“What was interesting about all of them was that they had different backstories, different provenance-related stories,” de Menil says.

Documents and a video series gave students the background in concise chunks — the law of antiquities, short histories of the objects, guidelines for questions to ask and how the solutions would be judged.

“We didn’t give them a ton because a huge asset, especially to these ancient intractable problems, is having a beginner’s mindset and not being so entrenched in how things have always been done,” the law school’s Haque says.

Haque says the professors’ discussions to create a hackathon rubric were an enlightening example of interdisciplinary work. She saw how each discipline’s perspective played into a professor’s focus, with color and physical qualities important for art but not so much for computer science, for example.

“Our values would start to show,” Haque says. “Even if we don’t agree or see the same things …, what movement forward right now can we make? Then later on we … can improve it some more.”

“The dish … was very inspirational because it was a real, live cultural artifact. ... The fact that it had been in so many different places over time, the whole travel in the life of that object became kind of an anthem on a certain level for the whole project.” –Susan de Menil

Sarah Stone illustration of the interior of Sir Ashton Lever’s Holophusicon museum in London in 1785/State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

CROSSING THE THAMES AND LOSING PRESTIGE

With his Holophusicon failing in 1786, Ashton Lever decided to raffle its contents as a whole rather than auction his precious collection piecemeal.

A raffle ticket cost 1 guinea (enough for velvet breeches or a week’s wages for a skilled tradesman). The lucky winner, James Parkinson, with no museum experience, collected his jackpot.

Parkinson, variously described as lawyer, retailer of legal supplies, land agent, dentist or proprietor of a “pleasure garden,” moved the huge collection to a cheaper part of town across the Thames River. He lowered the ticket price and simplified the futuristic name to Leverian Museum.

It worked for 20 years until public interest waned. The British Museum wasn’t interested, so the collection succumbed at last to a piecemeal auction in 1806. A Baptist minister bought the Fiji dish and about 150 other items. He shipped them off to Devonshire to his wealthy brother-in-law, Richard Hall Clarke, who was obsessed with Capt. Cook.

As large British estates continued their decline á la “Downton Abbey,” Clarke’s heirs auctioned off the museum’s contents in 1967.

Three years later, his collection overflowing, Clarke built a fine new stone building on his Bridwell estate, with the unabashed purpose of paying tribute to his celebrity hero.

The dish resided quietly for 158 years in that Chapel Museum in western England, drawing occasional travelers hungry for a taste of Cook’s voyages.

As large British estates continued their decline á la “Downton Abbey,” Clarke’s heirs auctioned off the museum’s contents in 1967.

The dish would soon transform into a work of art.

Bridwell estate

HACKING AWAY FOR 24 HOURS

For the first time, the Wake Forest hackathon in March 2021 had to take place online because of COVID-19 restrictions. Students used a chat platform popular with video gamers.

It’s called Discord — an ironic twist, Haque notes, for an event calling for collaboration, creative thinking, quick decisions and bonding in the wee hours when silliness takes over tired minds. To help with the absence of pizzas delivered to conference rooms, students received snack packages at home.

The winning team consisted of Caulkins, Caitlin Kelly (JD ’22) and Kristen Kovach (JD ’21).

Caulkins handled the programming duties. He will begin in August as a satellite communications engineer with Peraton, an aerospace technology company, in the Washington, D.C., area, where he was an intern last summer. Kelly, with an undergraduate degree in art history from Mary Washington University and a freshly earned law degree, is headed for a job at entertainment startup Gala Games and its blockchain-based platform. Kovach is a patent attorney at Bookoff McAndrews, a Washington, D.C.-based firm.

Kelly focused as an undergraduate on community approaches to culture and repatriation, so the hackathon topic was “perfect for me,” she says. “I’ve always been about taking art history and trying to drag it into the future through the law.”

Kovach, drawn to the hackathon by Haque’s class, recognized that understanding blockchain “opens up my avenues for work” as a patent attorney.

The three students chose the Mexican ceramic piece for their hackathon proposal, and their win immediately earned them the chance to move to the next level: developing the framework and arguments for a blockchain tool that could handle histories of any object, including those as long and deep as the Fiji bowl’s.

De Menil connected the team to another not-for-profit called the Blockchain for Social Impact Coalition (BSIC) in New York City.

Ravi Srinivasan, a global technology consultant and BSIC board member, volunteered to help the team with key elements and workflow for a functional prototype of an app or system that museums could use.

During the summer, Caulkins taught himself how to program using a blockchain. All three team members spent nights and weekends on the project while working full-time.

“It’s really interesting stuff that we’re doing, all totally revolutionary, innovative,” Caulkins says.

Kelly says she recognized that attorneys can be the “the killjoy” by always looking for potential obstacles, but the team appreciated a cautious perspective.

Kovach says taking action rather than working in hypotheticals was rewarding. “Creating something new is something that we don’t always get to do.”

They doubled down to find answers. “We’re doing new things every single day, so it’s not like you’re going to Google your issue and find somebody who’s done it,” Caulkins says. “You’re going to have to solve those problems. And we have, so I’m really proud of our whole team.”

“We’re doing new things every single day, so it’s not like you’re going to Google your issue and find somebody who’s done it. You’re going to have to solve those problems. And we have, so I’m really proud of our whole team.”

JOINING THE 1960s BOHEMIAN ART WORLD

In the 1967 auction of the Chapel Museum contents, the Fiji dish drew the attention of London art dealer Ernest Ohly. He bought it for the Abbey Art Centre, an art colony with a small ethnographic museum in an old barn, where artists borrowed objects to sketch.

The dish didn’t stay there long. Its time had come.

Western societies did not initially consider non-European cultural objects as art. But in the 1960s, the high-priced art market grew enamored of the beauty and craftsmanship of African and South Pacific tribal art, which had influenced cubism and artists such as Picasso. Ohly was a trendsetter in making London the center of attention for tribal art. Another top dealer, Ralph Nash, bought the dish and resold it to Alexander Martin for his new African and Oceania art gallery in posh St. James Square.

George Ortiz/Courtesy of George Ortiz Collection

Martin’s catalog caught the eye of George Ortiz, one of the foremost collectors of African and Oceanic art in the world. Ortiz’s father was the Bolivian ambassador to France, and his maternal grandfather was the “Andean Rockefeller,” Bolivian tin-mining magnate Simón I. Patiño.

George and Catherine Ortiz plead on TV in October 1977 for the return of their kidnapped 5-year-old daughter, Graziella. Photos/Radio Télévision Suisse

George Ortiz, who began collecting in 1944, grew up in Paris, was educated in the United Kingdom and the United States, then briefly read philosophy at Harvard before a journey to Greece changed his life. He began amassing one of the premier collections of ancient art in private hands.

In October 1977, kidnappers snatched Ortiz’s 5-year-old daughter, Graziella, from her chauffeur’s car in Switzerland and issued a $2 million ransom demand. Ortiz had spent much of his family wealth on collecting and had to borrow the ransom money. The kidnappers returned the little girl a week later. One kidnapper was found dead, and the others were caught and imprisoned, but most of the money was never recovered.

The dish was on display at a Honolulu museum for an exhibit on Capt. Cook, but before the exhibit ended, Ortiz announced that he would sell some of his collection to repay the ransom loans. His alternative was to lose the 18th-century Swiss manor house he had lovingly restored. “My family needs somewhere to live, so I had no choice,” he told The Washington Post. He consigned 234 pieces, including the dish, to Sotheby’s in London.

AN IDEA EMERGES AT CASA ARTOM

In 1978, J. Gordon Hanes Jr. (LL.D. ’92) was visiting with Professor of Anthropology E. Pendleton “Pen” Banks at Wake Forest’s Casa Artom during a vacation in Venice when the two devised a plan.

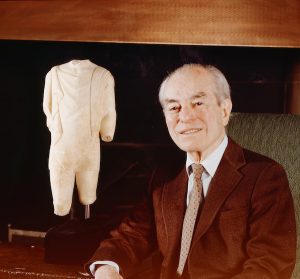

J. Gordon Hanes Jr. (LL.D. ‘92)

Hanes, the head of textile manufacturer Hanes Corp., was a well-known philanthropist and supporter of arts and cultural institutions. Banks had founded Wake Forest’s anthropology museum in 1963 as the Museum of Man.

Banks had little funding to acquire permanent collections, so Hanes resolved to buy pieces from the Ortiz collection for Wake Forest. The 31 pieces he donated included the Fiji dish. The gift launched the growth of acquisitions, and he donated hundreds more items before his death in 1995.

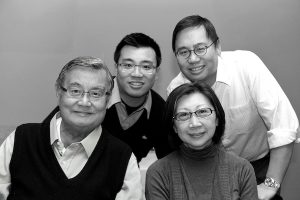

The museum has flourished, with 30,000 items from more than 90 countries. It moved in 2020 to a newly renovated, larger space in Arnold Palmer Hall. It was renamed last year for the late entrepreneur and philanthropist Timothy S. Y. Lam (’60), who donated his collection of more than 500 Chinese ceramics from the Tang Dynasty (618-907). A historic gift from Lam’s wife, Ellen, and their sons, Tim (’93) and Marcus (’98), made the expansion possible.

ASIDE FROM THE DISH AND 233 PIECES

In 1994 the Royal Academy of Arts in London had exhibited George Ortiz’ remaining collection. The trove was considered “breathtaking,” The Independent newspaper reported. Many museums have shown the collection, which remains in Switzerland.

Not everyone lauded Ortiz. British archaeologist Lord Colin Renfrew criticized the Royal Academy exhibit for “the large-scale looting which is the ultimate source of so much of what he is able to exhibit.”

Ortiz’s collection had not managed to escape the large network of smugglers, looters and market dealers who turned a blind eye. After 15 years of legal struggles, he received a short, suspended sentence on a 1961 charge of receiving stolen property. Ortiz was emblematic of those caught between saving treasured ancient objects and receiving looted artifacts.

With only her fascination with the small Fiji dish connecting Susan de Menil to George Ortiz, de Menil nevertheless knows the ethical conundrums antiquities can raise, and such issues are gaining more attention.

France is examining how to repatriate 90,000 museum artifacts from sub-Saharan Africa. The Association of Art Museum Curators organized its 2021 virtual conference around issues of appropriation, colonialism, identity and a culture of silence among curators.

The group at Wake Forest was still working on its project as this story was being written. By this summer, the team expects to have completed a white paper laying out how and why their blockchain tool is possible and useful, perhaps in the form of an app, Srinivasan says.

Timothy S. Y. Lam (‘60), his wife, Ellen, and their sons, Marcus (‘98), center, and Tim (‘93).

He is helping the team assess the business prospects, which could lead to investors or interested parties developing a marketable tool. The students’ longer-term involvement remains to be seen, but they are members of the founding team with whatever that brings. With millions of artifacts in private hands, Srinivasan says, owners who want better provenance records are the most likely users.

Like Srinivasan, Christina Elson, a business-oriented Wake Forest faculty member, sees the possibilities for a tangible outcome for the Wake Forest blockchain experiment. Elson, who leads the Center for the Study of Capitalism, says she came to the project to help drive thinking about the many business implications of blockchain technology. She is the center’s John A. Allison IV executive director and also is an anthropologist.

The ability to track antiquities benefits museums. The ability to track art, from a physical painting to digital art, offers value to an artist who can continue to receive revenue rather than a one-time payment under the one-owner model. And new models of ownership create the opportunity for new business models, as well as new ethical issues, Elson says.

“You want as many people as possible to be able to engage in the market and be able to have opportunities in the market,” Elson says. “And these kinds of technologies help provide that.”

De Menil says of the project: “Honestly, the winds could not have blown more in our favor if we had tried to arrange a wind machine.”

“Blockchain for good — we’re helping to define what this is. And most people don’t even know what blockchain is. –Rogan Kersh

AN ACADEMIC SHIFT

The multidimensional team at Wake Forest is part of an academic shift, too.

Universities have become accustomed to “two close cousins who collaborate together,” such as chemistry and biology (biochemistry) or political science and economics, Provost Kersh says. The Wake Forest project brings together parties that are much farther apart on the disciplinary chart.

Kersh says de Menil is “doing something really pathbreaking. We’re providing some of the intellectual underpinnings, … then … it’s taking the radical collaboration even farther to go outside the University, to partner with a nonprofit, thanks to a connection with a Wake parent.

“Blockchain for good — we’re helping to define what this is. And most people don’t even know what blockchain is.”

As for the Fiji dish, it sits serenely in its case on campus, with a mini-exhibit that tells the story of its travels through time, and its provenance — so far.