Frank Telewski knows where the bodies — make that bottles — are buried on Michigan State University’s vast campus in East Lansing. But he’s not telling.

Somewhere on the campus is a time capsule of bottles filled with seeds, buried more than 140 years ago to measure how long seeds can lie dormant underground and still germinate. Scientists at MSU dig up a bottle every 20 years to unlock the mysteries of the seeds. Already one of the longest-running science experiments in the world, it is scheduled to last another 78 years, until 2100.

The secret location of the bottles was passed down through several generations of

MSU professors until Telewski (Ph.D. ’83) was given the map marking the spot and entrusted to lead the Beal Seed Experiment. The only clue he shares about the location is that it’s somewhere on the 5,300-acre campus, which isn’t much help considering MSU is 15 times larger than Wake Forest’s Reynolda Campus.

When I ask him if thousands of students walk by it without knowing what lies beneath their feet, he offers only, “I don’t know that there are thousands, but yes, people walk by it every day. It’s not a heavily trafficked area. It’s a little bit off the beaten path.”

Telewski, 67, retired last year after nearly three decades at MSU as a plant biology professor and director of the W.J. Beal Botanical Garden and Campus Arboretum. He first heard about the seed experiment when he was studying for his Ph.D. in biology at Wake Forest, never imagining that he would lead the project one day.

The experiment began in 1879 when Rutherford B. Hayes was president of the 38 states in the United States. William James Beal, a botanist at what was then the State Agricultural College, wanted to help local farmers with a common problem that still vexes gardeners today: Why do those pesky weeds they hoed from their fields every year keep coming back year after year? As farmers plowed their fields, they would expose new batches of seeds previously not exposed to sunlight, and the freshly plowed field would fill with weeds again.

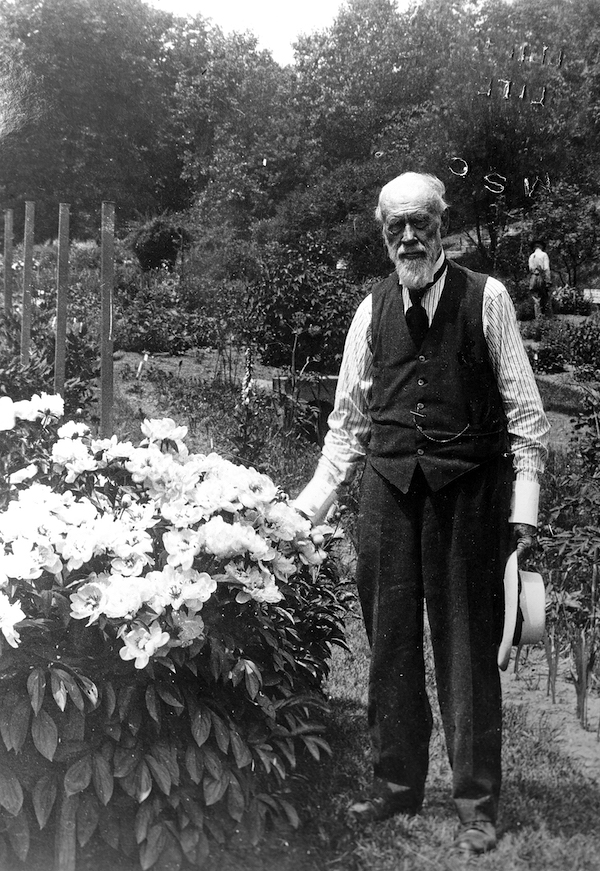

Botanist William James Beal started the garden in 1873 and his seed experiment six years later. (Photo: MSU University Archives & Historical Collections)

To try to find out how long seeds can survive in the soil, Beal collected freshly grown seeds from 21 species of farm weeds found in the area, including chickweed, ragweed and black mustard. Then he filled 20 ordinary, pint-sized glass bottles with a mix of moderately moist soil and seeds. He put 1,050 seeds — 50 seeds from each of the 21 different species — in each bottle.

Beal buried the bottles along a sandy knoll on the campus. His original plan was that he — and his successors — would dig up a bottle every five years. The study, intended to last 100 years, was prolonged by extending the time between digging up bottles to 10 years, then 20 years. What would have been bad news for Beal’s farmers is good news for MSU scientists today: Some of the seeds from 1879 are still sprouting.

Telewski joined the project in time to carefully remove a cracked bottle from its hiding place in 2000. In 2021, a year behind schedule because of COVID, he led the team that dug up the most recently recovered bottle. The experiment stokes the imagination with enough mystery and intrigue to captivate even nonbiologists among us.

He marvels at the convergence of history and science as he shows me

the bottle recovered last year, unglamorously stored in a small Walgreens cardboard box. “The last person to touch this bottle was professor Beal when he buried it in the ground,” he says. “This bottle has been waiting for us for 142 years with its secrets.”

Telewski can’t resist a reference to Woody Allen’s 1973 movie, “Sleeper,” in which Allen’s character wakes up 200 years in the future, but in this case, it’s the seeds waking up in the future.

- Telewski holds the Beal bottle recovered in 2021.

- An older bottle.

Only four bottles remain from the original cache of 20. As Telewski prepared to retire, he passed the map on to the next generation of scientists, including the first women on the team. Like Beal, he knows that he’ll never see the end of the experiment. “Beal planned it that way. I inherited it. He had the vision to say this unknown, this question, could take decades to answer. … It will literally cross three centuries and 220 years.”

He speaks for the trees

I met Telewski on the MSU campus on a sunny Tuesday morning in May. He’ll get around to talking about the Beal Seed Experiment soon enough, but first he gives me an introductory course on the history of MSU’s trees. After all, he dug up a bottle only twice in his time at MSU; he spent most of his time teaching about the trees and plants on campus. His graduate students called him The Lorax — the character from the Dr. Seuss book of the same name who tries to save a forest — an apt nickname given his mustached-appearance and his role as the keeper of MSU’s trees.

The Red Cedar River winds through the MSU campus.

We set off on a tour of campus, crossing a pedestrian bridge over the Red Cedar River that meanders through campus beneath a canopy of overhanging trees that create the feel of a forest. The historic part of campus is filled with trees but largely deserted with most of MSU’s 50,000 students on summer break. Some 9,600 students graduated earlier in the month, but a few students in green caps and gowns are posing for photographs with the larger-than-life bronze statue of the school’s mascot, Sparty, near Spartan Stadium. (No, the bottles aren’t buried under Sparty. That would be a little too obvious, the professor tells me.)

As we walk under red oaks and white oaks, some as much as 350 years old, Telewski is in his element: outdoors, teaching and sharing his love of nature. “This has been my joy my entire life,” he says. For nearly 29 years, in addition to teaching undergraduate and graduate students, he led the Beal Botanical Garden, the oldest continuously operated university botanical garden in the country, and oversaw the campus arboretum, about 2,100 acres in the developed part of campus.

The Beal garden includes flowering shrubs, wetland plants, endangered and threatened species native to Michigan and “useful plants,” such as those used to make medicines, dyes, perfumes and fibers.

William James Beal, the same professor who buried the bottles, started the botanical garden in 1873 as an “outdoor laboratory” for students. Today it’s a lush oasis on a normally busy campus, sandwiched in a hollow between several buildings and across the river from the football stadium. Although it’s been redesigned over the years, it’s remained true to Beal’s vision with collections that include endangered and threatened species native to Michigan and “useful plants,” such as those used to make medicines and textiles.

Telewski is most at home in the garden. He feels a special kinship with Beal, described by MSU as “the father of Michigan forestry,” who was well ahead of his time in promoting the conservation of forests. As we stroll through the garden, Telewski shares the stories of old friends: a Dawn Redwood, a Katsura tree and a Norway spruce planted in 1865.

“Every Spartan tree has a story,” he says. If it seems that he knows every tree on campus, it’s because he does.

He doesn’t talk to the trees, but the trees talk to him. “Every Spartan tree has a story,” he says. If it seems that he knows every tree on campus, it’s because he does. He led the mapping of an online guide of 22,000 trees in the developed part of campus. You can’t preserve the trees if you don’t know what you have, he says.

And like The Lorax, he fights for the trees. He once persuaded the MSU president to abandon plans to construct a building on a wooded lot that would have required the removal of swamp white oaks that grew from acorns planted by Beal in 1874. Another time, he talked planners into shifting the footprint of an academic building to save 150-year-old oak trees. If a tree rare to campus had to be removed for construction or because of damage or disease, he ensured that it was replaced.

Telewski counts the rings in a downed white oak on campus.

He has had a lasting impact preserving the trees on campus, says MSU campus planner Steve Troost. “His legacy is making sure that the arboretum has a diversity in its collection and it’s used as a teaching and research tool. He’s kind of a walking historian, too. He knows the history of Professor Beal and what he did for the campus and was very passionate about wanting to maintain that.”

As we continue walking around campus, we stop at a stubby, hollowed out trunk of a once mighty white oak, near the “sacred space,” a large pastoral expanse of grass and oak trees anchored by the 1928 gothic Beaumont Memorial Tower. Toppled during a 2016 storm, the tree doesn’t look like much, but wait, there’s a story. “That tree is about 400 years old,” Telewski says. “This was an old tree when the American Revolution happened. There were native Americans harvesting, maybe camping under that tree when it was a sapling. The things that tree has seen. And then somebody says, ‘It’s ugly, just cut it down.’”

The “sacred space,” anchored by the 1928 gothic Beaumont Memorial Tower, protects some of the oldest trees on the MSU campus; no buildings can be constructed in the space.

Not on his watch. The tree has one green branch jutting out from its trunk, and it has become an unlikely symbol of resilience on campus. “Where many of us saw only destruction, Professor Telewski saw life,” Christopher P. Long, dean of the College of Arts & Letters, wrote to first-year students in 2017, encouraging them to remain resilient, like the Resilient Tree.

A tyke bounding toward the greenhouse

Telewski’s path to MSU started in Fort Lee, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York. His father, an engineer for CBS in New York, planted a blue spruce tree in the family’s backyard every time a new child was born into the family; Frank was the last tree, No. 4. His father instilled in him a love of science and astronomy. His grandmother instilled a love of nature; his earliest memories are of her working in her vegetable and flower garden.

Curiosity makes the scientist, he says, and he was a curious little kid. He knew as far back as he can remember that he was going to become a botanist. When the other kids in his first-grade class ran to see the animals on a trip to the farm at Rutgers University, he ran to the greenhouse where he found a guy in a lab coat and peppered him with questions.

When friends bought pumpkins before Halloween, he grew his own. At Christmas one year, he put rooting hormones on the trunk of the family tree trying — unsuccessfully — to re-root it. He looked forward to the arrival of the Burpee seed catalog every year and read books on garden design to plan his own garden. By high school, he was treating potatoes and pines and Douglas firs with growth hormones.

“He’d be out hugging the trees and trying to find the oldest one and thinking about another project.”

He went to college at nearby Montclair State University, where he double majored in biology and chemistry and took care of the orchids and succulent plants in the school’s greenhouse. He earned a master’s degree in botany at Ohio University in Athens, studying under Professor Mordecai “Mark” Jaffe (P ’85, ’91). When Jaffe was named the Charles H. Babcock Professor of Botany at Wake Forest, Telewski followed him to Winston-Salem to study plant physiology for his Ph.D.

He found a diverse group of scientists and welcoming professors in Winston Hall: Charlie Allen (’39, MA ’41), Jerry Esch (P ’84), Tom Olive (’53), Bob Sullivan and Walter Flory (P ’66, ’67), all deceased now; and Robert Browne, Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74, P ’23), Ray Kuhn (P ’94), Carole Gibson and Pete Weigl. He heard about the Beal Seed Experiment from a classmate’s presentation. He thought it was interesting, but he was more focused on his research on Thigmomorphogenesis, how wind stress affects the growth patterns in trees.

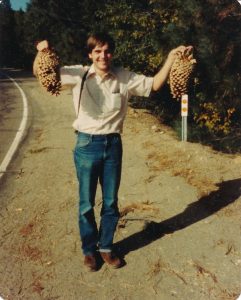

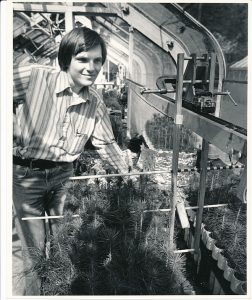

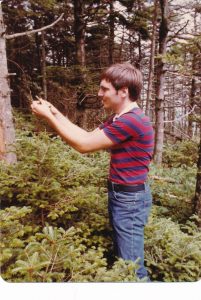

- Telewski found these pine cones during a visit to Palomar Mountain in California with Professor Mark Jaffe. He later hung the pine cones in his office at MSU. He first visited Palomar Mountain in high school when he presented a project on growing conifers exposed to growth regulators at the International Science and Engineering Fair in San Diego. (Photo by Mark Jaffe)

- Telewski set up an experiment with a model train and loblolly pines in a greenhouse at Reynolda Gardens. (Photo by Charlie Buchanan)

- Conducting research on Fraiser firs on Roan Mountain in North Carolina. (Photos by Jim Ha)

- Conducting research on Fraiser firs on Roan Mountain in North Carolina. (Photos by Jim Ha)

Jim Ha (MA ’83), who was studying animal ecology with Weigl, got to know Telewski. Ha’s research on fox squirrels required frequent trips to a longleaf pine forest near Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Telewski would tag along to help. “If it was pine trees, he’d go anywhere,” says Ha, a retired animal behaviorist and research professor in psychology at the University of Washington. “He’d be out hugging the trees and trying to find the oldest one and thinking about another project.” In turn, Ha helped Telewski conduct research on Frasier firs on Roan Mountain in North Carolina.

Telewski rigged his own experiment in a greenhouse at Reynolda Gardens by setting up a model train track — model railroading is a longtime hobby — over trays of loblolly pine seedlings. Once a day, a timer would go off, sending the locomotive up and down the track; a dowel attached to the locomotive brushed back and forth over the seedlings, duplicating the effect of wind on trees in nature.

Professor William James Beal started his seed experiment in 1879 when he buried 20 glass bottles filled with seeds on the campus of what was then the State Agricultural College. (Photo: MSU University Archives & Historical Collections)

Ken Bridle (MA ’85, Ph.D. ’91) was an undergraduate at Ohio University, working in Jaffe’s lab, when he met Telewski. Bridle also followed Jaffe to Wake Forest. He and Telewski were roommates in Ohio and then in an apartment in Bethabara, a 15-minute bike ride for them to campus. By the time Telewski ended his greenhouse experiment, Bridle had already bought the house he still lives in today in Walnut Cove, North Carolina, and he planted some of Telewski’s pine seedlings in his yard. “I have some of his babies that are 40-something years old now.”

His friend “has a childlike enthusiasm for the things that he likes, like trains and all things Disney, and a passion for trees,” said Bridle, who retired in June as stewardship and inventory director of the Piedmont Land Conservancy in Greensboro, North Carolina. “He’s always been interesting and entertaining and eclectic.”

After receiving his Ph.D. in 1983, Telewski joined the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona in Tucson as an assistant professor. He moved back across the country in 1990 to become director of the Buffalo and Erie County Botanical Gardens, designed partially by Frederick Law Olmstead, and an associate adjunct professor of biology at the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Wanting to teach more, he joined the MSU faculty in 1993 and rediscovered the Beal Seed Experiment.

The “secret society” begins digging for the bottles in 2021.

The ‘secret society’ repeats the dig

Only time can answer some questions — such as how long seeds can last in the

soil — leading William James Beal to bury his artificial seed bank in the Michigan soil in the fall of 1879.

Beal buried his 20 pint-sized bottles 18-inches deep, surrounded by 10-inch concrete walls, but open at the top. He placed the bottles close enough to the surface to replicate natural conditions, but not close enough to be accidentally dug up. He wrote that he left the bottles “uncorked and placed with the mouth slanting downward so that water could not accumulate about the seeds.”

Beal dug up his first bottle in 1884 and planted the seeds. He kept good records; seeds from 13 of the 20 species germinated that first year. All 50 seeds of Capsella bursa-pastoris (shepherd’s purse) grew, but only one of the 50 Malva rotundifola (low mallow) seeds did. Some of the species never germinated, but at least one seed of more than half the species germinated for the first 25 years before tailing off. By the 100th year, in 1980, only a handful of seeds from three species were still germinating.

When Beal retired, he passed the experiment on to a colleague, who passed it on to another and so on. Professor Jan Zeevaart invited Telewski to join the project in 2000 when they dug up the cracked bottle. When Zeevaart died in 2009, Telewski became the seventh keeper of the map and the only scientist who knew where the bottles were buried. (Groundskeepers at MSU also have a map, to prevent backhoe mistakes.)

Years later, Telewski gave a copy of the map to David Lowry, an environmental plant physiologist, “just in case” something happened. Lowry was in college when he first heard about a “secret society that goes out in the middle of the night and digs up a bottle and plants the seeds.”

A few months later, Telewski suffered a stroke. Although he’s largely recovered, Telewski says his health scare reinforced the importance of being a good steward of what Beal started and “passing the ball to the next generation.” He later added three other scientists to the team: Lars Brudvig, a restoration ecologist; Margaret Fleming, a molecular biologist who previously worked at the U.S. Department of Agriculture seed vault in Fort Collins, Colorado; and Marjorie Weber, an MSU expert in ecology and evolution.

“Wow! Oh, wow!

Hello, bottles!”

Snow flurries were falling when Telewski and his fellow scientists gathered on campus one cold April morning last year to dig up the 16th bottle. The “excavation,” as Telewski calls it, always takes place in the dark to keep the location secret and to make sure the seeds aren’t prematurely exposed to sunlight.

For the first time, MSU videographers were allowed to come along to film the dig. (The New York Times, NPR and other national media outlets later ran stories on the experiment.) The video opens with Telewski and his colleagues, armed with a shovel, trowel and headlamps with green filters, trudging off to the secret location.

Telewski uses his map and a tape measure to triangulate where the bottles are buried. He begins digging, but they don’t find the bottles. Lowry realizes they’re reading the map wrong, and they move 2 feet to the left and begin digging a new hole. With sunrise quickly approaching, Weber leans into the hole, digs with her hands and pulls out a glass bottle. “Wow! Oh, wow! Hello, bottles!” Telewski exclaims, as the group breaks into applause.

Later that morning in the plant biology building, they take turns dumping the bottle’s stash of seeds into a black tray filled with sterile potting soil. The soil mix is lightly watered and placed in a growth chamber. Then the waiting begins. The video ends as Lowry sees the first shoots of Verbascum blattaria, or moth mullein, push their way through the soil.

The seeds are later exposed to a cold treatment to simulate a winter and smoke treatments to simulate a wildfire. More Verbascum blattaria and a Verbascum hybrid sprout over the next several months as the soil is occasionally disturbed.

Even if nothing had grown, it still would have been a scientific result, although Telewski tells me later that he’s happy that his colleagues had the joy of seeing seeds sprout. “Going back to my childhood and seeing the magic of a seed come out and grow, … it’s the promise of nature,” he says.

Verbascum blattaria didn’t appear until the 1930 bottle was unearthed; now it’s the last survivor. But it’s also a bit of a mystery, Telewski says. Beal didn’t include Verbascum blattaria on the list of seeds in the bottles, although he did list a close cousin, Verbascum thapsus, the common mullein, which germinated for decades. Beal, or perhaps students helping him collect the seeds, might have misidentified the tiny seeds of the two species. But it really doesn’t matter, Telewski says, since seeds buried in 1879, whether they’re Verbascum blattaria or Verbascum thapsus, are still germinating.

- Telewski spreads seeds from the bottle in a sterile soil mix to see if any germinate.

- A week later, verbascum blattaria, or moth mullein, emerges.

Lowry tells me that Beal’s experiment is moving beyond seed viability to greater questions “about life in general and how it’s evolved into all these different forms. Some of these forms include seeds that last a long time in the soil … while others do not. This one species (Verbascum blattaria) just lasts so much longer, and it doesn’t have anything particularly noticeable about the characteristics of the seeds. All of them have very small seeds; small seed plants tend not to last long in the soil, but this one happens to last a really long time. The size of the seeds or the dormancy of the seeds may evolve in response to climate change.”

Telewski takes me to Fleming’s lab, where she shows me trays of 2-foot high Verbascum blattaria plants grown from the 1879 seeds and planted in 2021. Fleming says extracting and analyzing DNA from some of the species that haven’t germinated in decades can reveal what’s going on inside the seeds. Are the seeds really dead, or could they still be metabolically alive but have lost their ability to germinate?

“Finding that seeds can be in-between alive and dead is new and exciting because with the right conditions, ‘zombie’ seeds might be able to germinate,” says Fleming, who is starting a new long-term seed burial experiment, Beal 2.0, to follow up on Beal’s work. “Also, we don’t know why Verbascum seeds have such great longevity, so examining their DNA might also identify genes involved in longevity.”

Beal’s experiment holds the promise of spurring applications for agriculture and conservation for another 80 years. Plant ecologists are gaining insight into how natural seed banks can restore ecosystems after fires, floods or high winds. It can unravel the mysteries of why some plants have seeds that persist for decades while others don’t. Seeds don’t all respond to the same cues to germinate; the seeds of plants thought lost may still be alive underground, waiting for the right signals to come back to life.

Beal’s original question — how long can seeds remain viable in the soil? — still remains unanswered.

Verbascum blattaria, or moth mullein, grows from the seeds buried underground for 142 years.

Everyone has a seed vault

Telewski ends our campus tour back in the Beal Botanical Garden. Lush trees and shrubs on the slopes surrounding the garden screen the adjacent buildings. Some of the plants grown from Beal’s seeds end up here in the garden he started. Noise and crowds spill over into the garden on fall football Saturdays, but today it’s quiet and peaceful.

“We have something in the botanical gardens field called ‘plant blindness,’” Telewski says as we sit on a bench under Eastern flowering dogwoods and Kousa Dogwoods by a small man-made pool. “How many people walk through their daily life and have no idea what’s going on around them in terms of plant life? Whether it’s in downtown Manhattan, with street trees, or whether you’re out in the middle of the country or in a forest, … we depend on all plant life for our survival.

“One thing that I think everybody senses,” he continues, “especially if you live in an urban environment, when you walk into a green space, if it’s a park or a garden and you’re surrounded by trees and plants, or if you go for a walk on Roan Mountain (on the North Carolina/Tennessee border) or along the Appalachian Trail or on the Outer Banks or walk amongst the longleaf pines in North Carolina or the pines in Northern Michigan, you can just feel your body relax.”

Telewski lives with his wife, Jill, in Mason, Michigan, about a 20-minute drive from MSU. There, on 7 acres, he has a vegetable garden and flower garden — inspired by Claude Monet’s garden at Giverny, France, minus the pond and lily pads — and a mini forest of black walnut trees, elms, fir trees, oaks, sugar maples and white pines that he planted himself.

“How many people walk through their daily life and have no idea what’s going on around them in terms of plant life?”

Look no farther than your own backyard to discover the secrets of nature, he says. “Dig a hole, mess up the soil and see what germinates, and ponder how long that seed’s been there. From last year? From a hundred years ago? We all have a seed vault in our backyard. Any patch of dirt is a seed vault.”

I try one more time to learn where the last four bottles are buried. And this time, he answers, sort of, with a hearty laugh, but I was still no closer to finding them.

“Somewhere, while we were walking around today, we did walk past the bottles.”

Telewski in the Beal Botanical Garden.<br /> <br /> (About the photographer: Derrick L. Turner, a graduate of MSU, has been a photographer there for 34 years. He knows where the bottles are buried but is sworn to secrecy.)