Illustration by Jeffrey Smith

Not long ago there was a golden age of newspapers.

One of the giants of that age, who was also a prime mover of the modern Winston-Salem, had deep Wake Forest roots. His name was Wallace Carroll.

Carroll (D.Litt. ’73) was the editor and publisher of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, one of America’s best regional newspapers. Then, from 1974 to 1984 he taught “An Editor Looks at the Rights of American Citizens, 1965 – present,” which reinforced Wake Forest students’ understanding of the precious rights we’re afforded under our system of government.

Earlier, in the 1930s, he had been a United Press correspondent and bureau chief in Europe, covering the lead-up to and start of World War II and interviewing, among others, Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin and Dwight Eisenhower. In between two stints at the Journal and Sentinel, he ran news coverage of The New York Times’ Washington bureau, where famed Times columnist James Reston once told me: “I’ve never known a newspaperman with better judgment than Wally.”

All this is captured in the magnificent new biography “Century’s Witness: The Extraordinary Life of Journalist Wallace Carroll” by Mary Llewellyn McNeil (’78). She was inspired by Carroll while taking his class, only later discovering her brilliant but self-effacing professor was a journalistic legend. She decided to write a book about him.

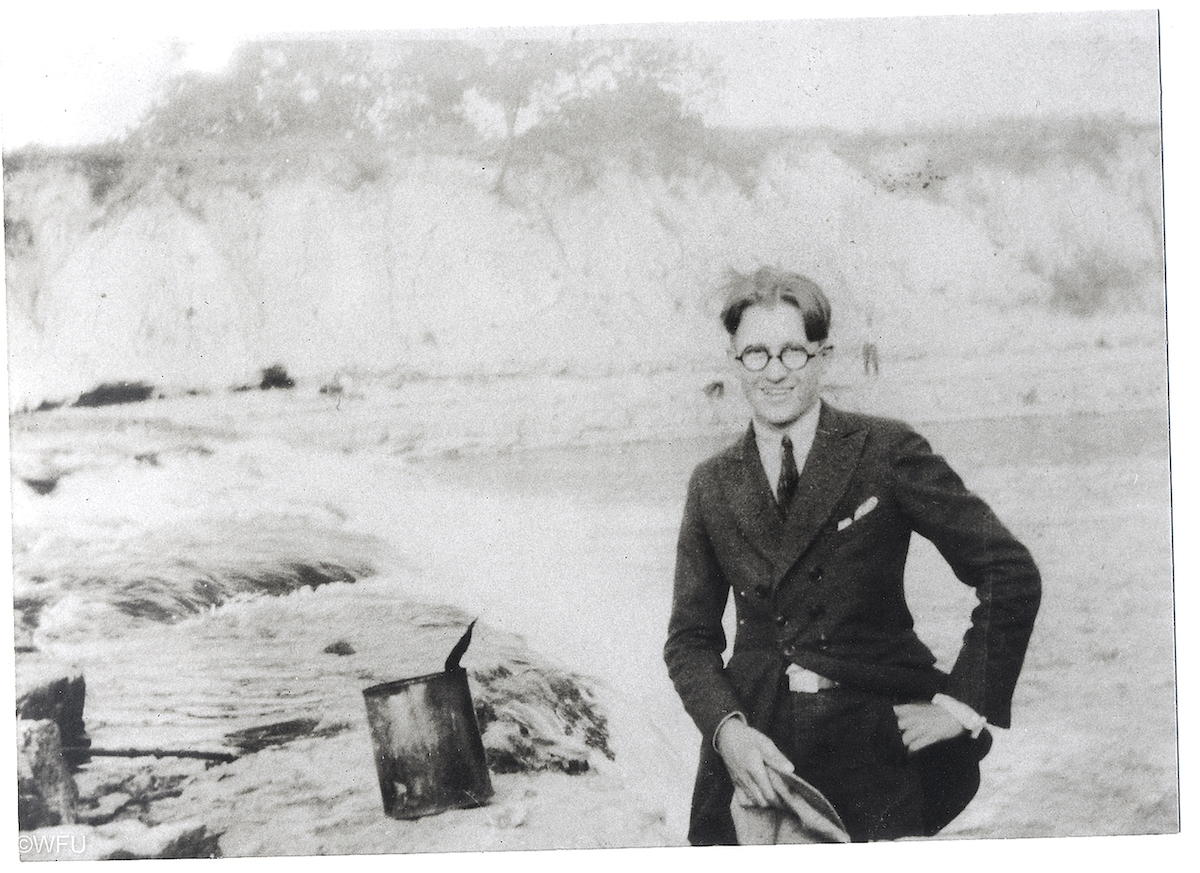

Wallace Carroll outside Paris in his early years. He became a London-based correspondent for United Press news service at age 22 and spent 14 years there and in Europe. Photo/Courtesy of Carroll family

Carroll’s story serves as a reminder of the importance of journalism in a liberal democracy and the daunting challenges it faces today. He would be horrified at the priority many newsrooms place on how many clicks a story gets. He rarely if ever did television programs; he was a newspaperman. Carroll died in 2002, and as much as I admired him, I sort of hoped he didn’t catch me on one of those ubiquitous cable programs. His close colleague Reston once asked me why I did those shows. I explained it was an opportunity to reach a broader audience, news habits were changing, blah, blah, blah.

“I see,” he replied. “Mid-life crisis.”

In Carroll’s age, newspapers played a central role in community life, political discourse and accountability. Today local news, to borrow a phrase, looks more like a vast wasteland.

Carroll believed, McNeil writes, that “journalism had a higher calling and that was to give citizens the information they need and deserve to know in order to preserve democracy.”

A handful of great national newspapers, The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal, are flourishing. They produce great journalism and are essential reading, adapting to the digital age. About 90 percent of the Times’ circulation of 9.2 million subscribers is digital.

But the business model has soured for most local papers. Since 2005, the country has lost more than a quarter of its newspapers. Others, such as the Chicago Tribune, once one of the country’s largest and most influential papers, are a mere shadow of what they once were due to huge staff reductions. Much-needed investigative reporting and accountability at most local news organizations are in sharp decline. Alden Global Capital, a hedge fund, has bought some 200 papers, usually cutting them to the bone and selling assets. The citizens of those communities suffer.

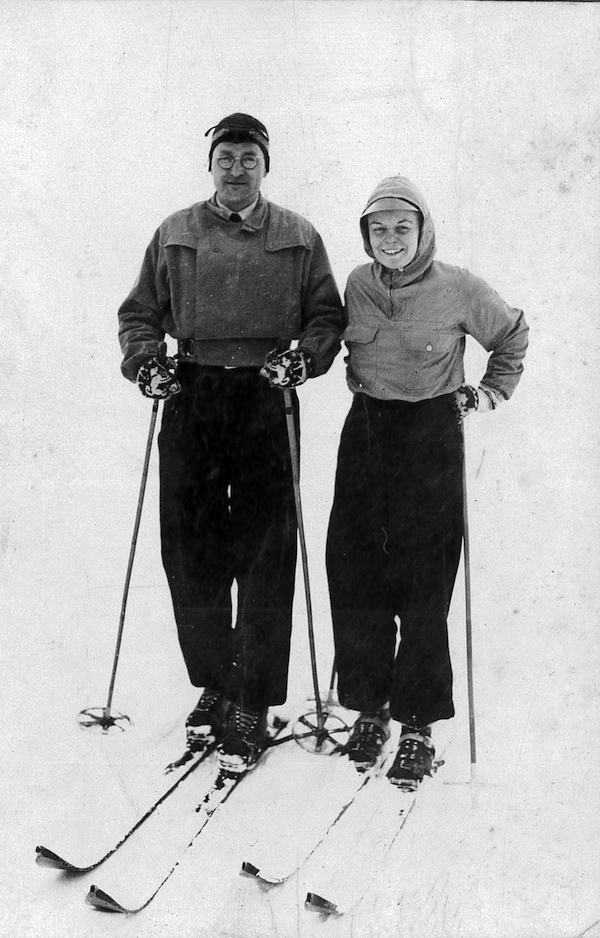

Wallace and Peggy Carroll in the Alps in 1938. Photo/Courtesy of Carroll family

There still is good journalism in North Carolina, though local ownership is rare. The Winston-Salem Journal and Greensboro News & Record are among the publications owned by Davenport, Iowa-based Lee Enterprises in 77 markets across 26 states. The Charlotte Observer and The (Raleigh) News & Observer are owned by Chatham Asset Management, headquartered in Chatham, New Jersey. This makes us even more appreciative of the journalism of Wallace Carroll. His stewardship of the Winston-Salem Journal began in 1949, when his high-powered diplomatic sources recommended him to the Journal’s owner, Gordon Gray (LL.D. ’51), later Secretary of the Army.

It was a good professional marriage — a committed local owner giving independence to a top-flight, experienced editor. Carroll hired talented young reporters like Tom Wicker (D.Litt. ’76), who would go on to national fame at The New York Times. Carroll set exacting standards for aggressive but careful reporting and clarity in writing.

“We would do well to remember the power of one man to speak truth and right wrong. It was journalism — and humanity — at their best.”

He left Winston-Salem in 1955 to direct the enormously talented New York Times Washington bureau. He returned to Winston-Salem eight years later as editor and publisher of the papers.

The second act was even better. North Carolina newspapers were playing an important role in the tense civil rights struggles; their leadership was a major reason North Carolina witnessed less violence and disruption than in other Southern states. Carroll and his paper were at the forefront of this effort.

There were no sacred cows. The paper gave extensive coverage to the 1964 U.S. Surgeon General’s report on the dangers of cigarette smoking. Carroll knew that would incur the wrath of the town’s largest employer, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. He took on the National Rifle Association and the gun lobby long before this became a popular cause. And the paper won a Pulitzer Prize in 1971 for its environmental reporting, which exposed the ravages of strip mining.

Children in a London suburb who were left homeless by German bombing in September 1940. Photo/The New York Times Paris Bureau Collection (USIA)

Carroll also played an integral role in the effort to locate what is now the UNC School of the Arts in Winston-Salem, and he was deeply involved in the life of the community. As Wake Forest Provost Emeritus Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) and his wife, Emily (MA ’62, P ’91, ’93), noted, the evolution of the city was due to “the intellectual work emanating from Marshall Street” (home of the Journal and Sentinel offices). Carroll and his equally talented wife, Peggy, “made us all citizens of the world,” they recalled.

He influenced national policy too. In 1968 Carroll wrote an editorial, “Vietnam — Quo Vadis,” (“Where do we go from here?”) in which the long-time Cold Warrior argued America should withdraw from Vietnam, as it was distracting us from the more important interests of countering the Soviet Union and Communist China. His old friend, former U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson, read the editorial to President Lyndon B. Johnson. A few days later, Johnson said he wouldn’t run for re-election and proposed de-escalating the conflict. (The same editorial might have been written about Afghanistan.)

Upon retirement, Carroll was a natural teacher for his courses on constitutional rights — including the First Amendment — at Wake Forest, and he furthered his teaching by bringing distinguished guests to campus: Reston, Acheson and columnist George Will, among others. “Everything Wallace Carroll said seemed relevant to the real world outside the Wake Forest bubble. I could sense everything we learned would be important,” remembers Maria Henson (’82), who spent 27 years at newspapers and is now the editor of this magazine. “I remember how regally he stood, how elegantly he dressed and how regularly he strolled across the campus for his swim sessions.”

A January 1942 news story in the Marquette Tribune in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Carroll’s hometown. He is shown with Russian generals after the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. He was among the first correspondents in the fall of 1941 to enter the country and report that Soviet troops could resist the invasion. Photo/Marquette Tribune

Regal and elegant, but also self-effacing and more daring than many imagined. Students had no idea he had been a renowned reporter or knew the danger he faced in covering Hitler’s bombing blitz of London or reporting from Moscow when the Nazi invaders were on the doorsteps. McNeil’s book captures his harrowing 2½-month trip in 1941 from Russia back to New York: rickety planes, flying low to avoid anti-aircraft fire; unsteady rail travel; a 100-mile taxi ride through the Iranian desert trying to avoid nomad bandits; and ultimately completion of a journey that took him through Asia and across the Pacific. One of his final stops was in Hawaii a week after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Carroll was the first reporter to see all the devastation

- Wreckage at the U.S. Naval Air Station at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii after the Japanese bombing on Dec. 7, 1941. Carroll was early on the scene. Photo/Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images from Alamy

- London buses en route to King’s Cross bombed by the Nazis. Photo/Shawshots/Alamy

In his “retirement,” as well as teaching at Wake Forest, he and Peggy fought the power companies’ efforts, backed by Big Labor, to put dams on the New River, which would have been a disaster for the environment and farmers. Carroll used his contacts with public figures and journalists in a remarkable campaign to win its designation as a wild and scenic river, prohibiting such development. When President Gerald Ford (LL.D. ’80, P ’72) signed the legislation protecting the river and its valley in 1976, the Carrolls were in the Rose Garden. The New River has now become this country’s most recently designated national park: the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve.

Mary Llewellyn McNeil (’78)

“Century’s Witness” captures all these stories about a great man and his era, and it provides lessons to contemporary journalists. The dark days of U.S. Sen. Joe McCarthy’s Communist witch hunt in the 1950s caused Carroll to decry journalism’s “tyranny of objectivity” by reporting without verifying or questioning, which rewarded the “Big Lies” spun by the Wisconsin demagogue. (Something we should take note of today.)

Carroll believed, McNeil writes, that “journalism had a higher calling and that was to give citizens the information they need and deserve to know in order to preserve democracy.”

“We would do well to remember the power of one man to speak truth and right wrong,” Ed and Emily Wilson observed. “It was journalism — and humanity — at their best.”

On a personal note, Carroll changed my life. My last year at Wake Forest I worked part time at the Winston-Salem Journal. That spring editors offered me a job, but I had already accepted one at The Wall Street Journal.

The Charlotte Observer had held an annual North and South Carolina college newspaper contest and, for pieces in the Old Gold & Black, I had won several awards. At the Charlotte awards dinner, an editor offered me a job. I told him I was headed to The Wall Street Journal. “That’s a big mistake,” he said. “They are notorious for hiring young reporters, and you never hear about them again.”

Petrified my career was over before it began, I went to see Mr. Carroll to ask if the Winston-Salem Journal offer still stood. “That man doesn’t know what he’s talking about,” he said. “There is no paper in the country that better achieves its objectives than The Wall Street Journal. Whether you stay for a year or 10 years, you will learn and be a better journalist.”

I stayed for almost 40.

Al Hunt (’65, D.Litt. ’91, P ’11), writes a weekly column for “The Hill” and is a co-host of the Politics War Room podcast. He is the former executive editor of Bloomberg News and previously served as reporter, bureau chief and Washington editor for The Wall Street Journal. For almost a quarter century he wrote a column on politics for The Wall Street Journal, then later for the International New York Times and Bloomberg View. He is a Life Trustee on the University Board of Trustees.

Al Hunt (’65, D.Litt. ’91, P ’11), writes a weekly column for “The Hill” and is a co-host of the Politics War Room podcast. He is the former executive editor of Bloomberg News and previously served as reporter, bureau chief and Washington editor for The Wall Street Journal. For almost a quarter century he wrote a column on politics for The Wall Street Journal, then later for the International New York Times and Bloomberg View. He is a Life Trustee on the University Board of Trustees.