With some philosophy programs under attack because of higher education budget cuts and notions of “What are students going to do with that major after graduation?”—here’s a happy surprise:

Wake Forest’s philosophy program has more majors and minors than ever.

As of Spring 2022, there were 96 declared majors and 81 declared minors (177 sophomores, juniors and seniors), according to Wake Forest’s Office of Institutional Research.

In 2021-22, there were 67 students with a major or minor in philosophy who graduated, compared with 17 in 1997-98, according to data in the research office’s annual Factbook collection. That’s an increase of nearly 300%.

Top, Tarantula Nebula by the James Webb Telescope; above, Messier 82 starburst galaxy. Cosmos photo credits below the story

Philosophy is still among the smaller departments chosen as a major, but the undergraduate program has accomplished its growth without even offering graduate-level programs.

By comparison, the larger Department of Politics & International Affairs, with 180 majors and minors graduating in 2021-22, grew 125% during the same period. History graduated fewer majors but more minors during that time frame, data indicate, and English graduated fewer majors but attracted students by establishing new minors in writing and creative writing.

"Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing wonder and awe,

the more often and the more intensely the mind of thought

is drawn to them: the starry heavens above me

and the moral law within me."

Above: Close-up of the Tarantula Nebula

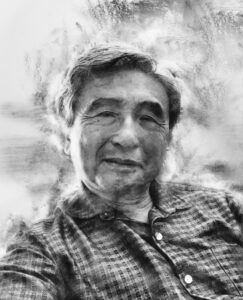

To get a sense of how far the philosophy department has come, just talk to Win-chiat Lee, a philosophy professor who holds the Tatum Family Faculty Fellowship. He came to Wake Forest in 1983 and chaired the department for nearly 20 years, 1993-2001 and 2012-2021.

Win-chiat Lee

“When I came into the department, we were struggling with the number of majors. It rarely went beyond a single digit for each graduating class,” says Lee.

Wake Forest’s philosophy department has done better than the national trends in attracting majors over the last two decades.

The numbers of philosophy undergraduate degrees nationally rose steadily from the mid-1980s through 2013, began dropping, then began recovering slowly from 2017 to 2020, according to the National Center for Education Statistics and DATA USA.

Some colleges have eliminated philosophy programs during the pandemic or ongoing budget squeezes. But other universities have seen interest resurging before and during COVID, perhaps, some higher education watchers have suggested, reflecting the search for meaning in a world of global threats and a renewed popular media focus on the big questions in philosophy.

Helix Nebula

Let’s take a closer look at some of the theories of what has driven Wake Forest’s growth and how philosophy degrees have helped alumni find success in all sorts of fields — not just the ones you might expect, such as law, divinity and academia.

A DECADE OF INTENSE CHANGE

Of course, Wake Forest has more students today than it did decades ago, but the number of graduates majoring or minoring in philosophy has grown at a much faster rate than the nearly 40% increase in undergraduate degrees conferred since the Class of 1998 walked the stage.

One pivotal period for the philosophy department was 2001-2012, when Professor of Philosophy Ralph Kennedy, now emeritus, was chair. “Those were the boom years in terms of hiring new faculty,” says Lee. During that time, the department grew most years.

With new and more faculty came a greater variety of courses offered. For example, in the 2021-2022 academic bulletin, mixed in with classes revolving around ancient giants like Aristotle, Aquinas and Kant, you’ll now find classes with a modern twist, such as “Philosophy of Love and Friendship,” “Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art,” “Global Justice,” “Philosophical Theories in Bioethics,” “Contemporary Moral Problems,” “Main Streams of Chinese Philosophy” and “Freedom, Action and Responsibility.”

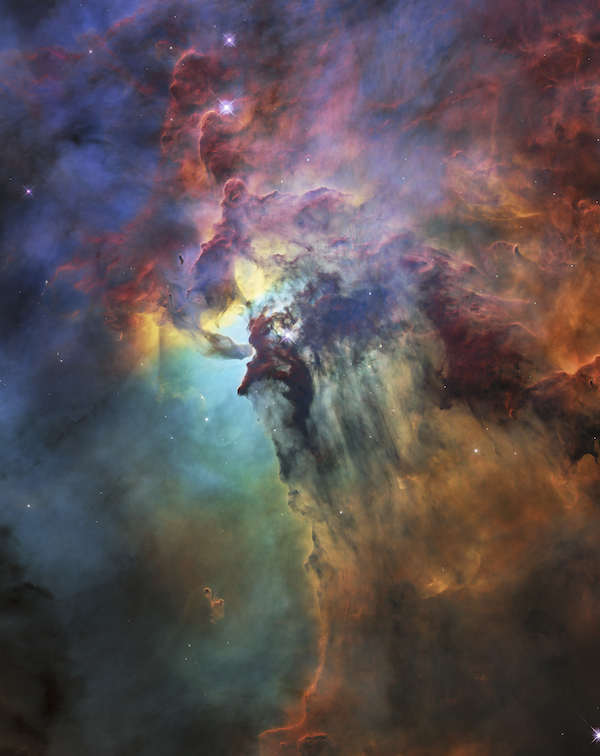

Lagoon Nebula

THE GIFT OF GIFTS

A statistic that distinguishes Wake Forest’s philosophy department is the gift funding it has received. The department has one of the highest levels in the College of Arts and Sciences, says Mike Haggas (P ’21), assistant dean of College Development.

To cite just a few examples, the funding helps pay for research leaves for faculty, professorships, conferences and curriculum development. It provides meals for the Braswell Philosophy Society, a club that meets Thursday nights for an hour in Tribble Hall to discuss political, social and moral issues. The club is so popular that an Old Gold & Black article in March 2022 titled “Philosophy Society Increases Intellectual Engagement” featured a photo with two dozen students in the philosophy library.

Gift funding allows the department to bring in cutting-edge philosophers as guest speakers. In this academic year, they include philosophy faculty from Dartmouth College, Georgetown University, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California, Berkeley.

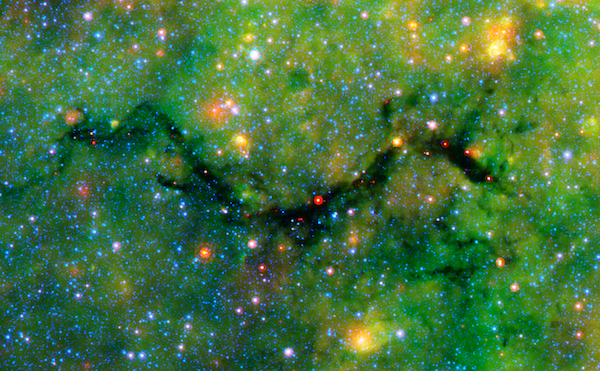

The Snake

Hiring talented and committed faculty adds to the positive experiences of students who become successful and capable of giving or facilitating funding for their alma mater. For philosophy, two multimillion-dollar endowments have helped the department thrive, Haggas says.

MOTIVATED PRACTITIONERS

Stavroula Glezakos

“The people in the department are really special,” says Associate Professor of Philosophy Stavroula Glezakos, who was hired in 2004 during the growth period of the early 2000s and has chaired the department since 2021. “There are people where, I’m like, ‘I knew they were productive researchers.’ And then you read the teaching evaluations and the way students write about them — they really are teacher-scholars. Everybody’s willing to put in extra time or extend themselves.”

Studies show that philosophy alumni in general often do well, in business and in pursuing graduate degrees, including law. Nationally, median earnings of those with bachelor’s degrees in philosophy exceed those of other humanities majors and were 16th among 50 majors overall, a study of 2016 data in The Wall Street Journal showed.

Many highly successful people — including LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, Flickr founder Stewart Butterfield, Nobel Prize-winning novelist Kazuo Ishiguro and the late civil rights activist and U.S. Rep. John Lewis — have lauded their study of philosophy and its impact on their lives.

Philosophy majors consistently perform at the top or near the top in graduate school admissions tests, according to the American Philosophical Association (APA). Philosophy majors are tops in law school admissions and generally trail only economics majors on law school exam scores, APA data show.

Pismis 24 star cluster

ASKING THE BIG QUESTIONS

Even as division requirements at Wake Forest changed and gave more students the chance to avoid the infamously difficult philosophy classes, growth continued. Before fall 2007, all students were required to take one introductory class in philosophy, one in religion and one in history. From fall 2007 to spring 2018, students could choose two classes from just one of those three departments. Students kept choosing philosophy. Today, students can choose two classes among four disciplines: philosophy, religion, history or women’s, gender and sexuality studies.

Alumni point to the impact their philosophy study produced in their professional and personal successes and explain what drew them to the esoteric discipline.

For Lysle Evans Betts (’82), it was a philosophy major and friend at Davidson College who inspired her to consider the subject, and she ended up double majoring in philosophy and religion at Wake Forest.

Charles M. Lewis

“I liked to ask around and say, ‘Who are the hardest professors?’ They tended to be the most interesting. My favorite thing was to be fascinated in class, and my least favorite thing was to be bored,” she says.

She took three philosophy classes — “Philosophy of Religion,” “Plato” and “Hegel, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche” — with Charles M. Lewis (’63, P ’13), professor emeritus and A.C. Reid Distinguished Teaching Fellow.

“He would come in with a small stack of index cards, sit at the head of the table and then ask deep questions and listen to what we said. We didn’t have a textbook or syllabus — only reading assignments from the original texts. We were graded on class participation and papers. He said the only way to get an A in his class was to make him think a thought that he’d never thought before. Isn’t that amazing?” she says.

"Let us permit nature to have her way. She understands her business better than we do."

Above: Witch’s Broom Nebula

Lewis confirms that Betts received an “A” in all three classes. His class notes, which he still has in his retirement, say, “She was well-prepared for involved seminar discussions. Good dialectical engagement. Personally invested in the ideas.”

The experience gave her a new sense of confidence. “I came away with a lot more trust in my own mind and my own ability to reason and think for myself. At that time, all the philosophy professors were male. Except in two philosophy classes, all my fellow classmates were male. Yet there was a clear gender egalitarianism; I was treated as a peer.”

Another perk for majors was getting a special key to the philosophy library, which Betts could enter any time, day or night. “It was so fun because only about seven or eight people who weren’t professors had keys. It was like our own special Hogwarts,” she says.

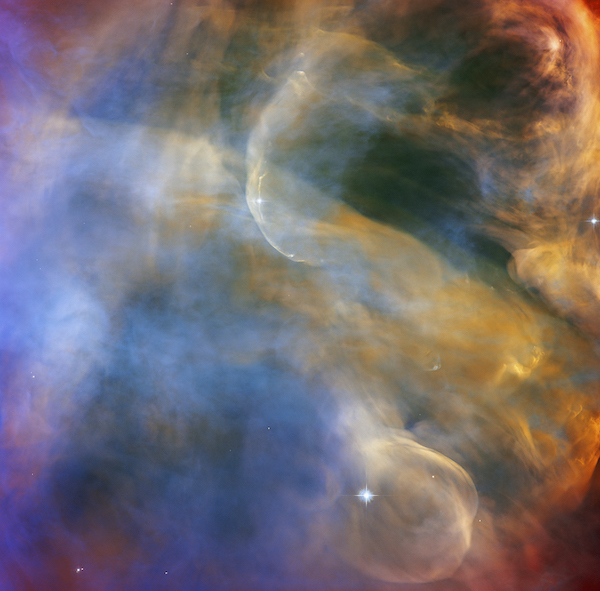

A celestial cloudscape in the Orion Nebula

After college, she worked as director of Christian education in a Presbyterian church and then as a county social worker, but a transformative experience with a therapist during troubles in her first marriage made her want to become a therapist.

“I’m from the small town of Henderson, North Carolina, and growing up, therapy was thought of as something mainly for people with severe mental illness,” she says.

Lysle Evans Betts

But overcoming her reluctance and talking with a therapist made her see her life through an entirely different lens. “The first time I saw a therapist, she said, ‘I don’t think your self-esteem is strong.’ And I said, ‘But isn’t that a good thing, to not think much of yourself because we’re taught as Christians that we’re supposed to be humble and not be proud?’” says Betts. “(The therapist) was a member of the same church I had grown up in, yet she saw positive self-regard as vital to health and well-being. That opened an important door for me.”

Betts later went to graduate school at North Carolina Central University and became a clinical mental health counselor, in private practice in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, since 1995.

“One of the ways my philosophy major helps me as a therapist is that lots of the people I work with are thinking about meaning, value, identity and purpose. They’re asking questions about themselves and their lives, like, ‘Who are we and why are we here?’ For me, those questions are familiar ground. It’s come full circle,” she says.

Crab Nebula

Betts says some therapists might get uncomfortable when patients bring up hot-button issues such as God, sex, death, religion or politics.

“One of the great things about a philosophy major at Wake Forest is that it explores all the nooks and crannies of any questions anybody might ask about being human, like how should we live and what’s the meaning of life? It pushes students to inquire all the way out to those edges, and that helped me a lot.”

DOUBLE MAJORING

Christian Miller

The relative ease of a double major in philosophy at Wake Forest — at least half the philosophy graduates in 2021-22 were double majors — might have encouraged the department’s growth. Requiring nine classes, or 27 hours, is “on the low end of what’s required for a major,” says A.C. Reid Professor of Philosophy Christian Miller. (English majors must complete 33 hours; history requires 31 hours.) “If a student can major in philosophy and something else, that can make the students — and maybe also the parents —feel a little calmer about us.”

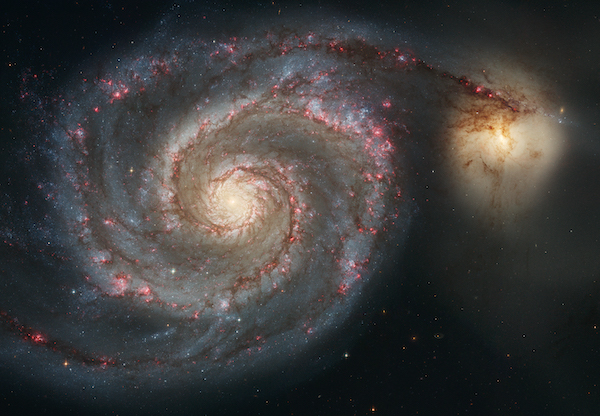

Whirlpool Galaxy

Faculty also have made a concerted effort to target younger students, helping to counter students’ impulse to procrastinate until their senior year to take a class known for difficulty in earning a high grade. When Miller arrived in 2004, “a lot of students … had heard that it was hard — a GPA killer — and maybe not so interesting,” he says. “We were slowly able to chip away at the reputation of the department to the point where it became a desirable place to go.”

For the past decade or so, he has taught his introductory “Problems of Philosophy” class only to first-year students, usually in the fall. “They’re brand new, very excited, highly motivated — not jaded or burned out. They do the reading and have a lot to say, and hopefully, they get hooked on it and want to take more.”

We wrestled with the question of identity over time. As a confused, aimless 19-year-old, it just blew me away. I thought, ‘You can study material like this and ponder these kinds of concepts?’”

HONING PERSUASIVE ARGUMENTS

David Klenk (’09) got hooked in an introductory philosophy class with Glezakos, “a wonderful professor who was just so accessible and made the material so interesting,” Klenk says.

“In her class, we’d do the Ship of Theseus thought experiment. If the ship is anchored in a port and you slowly replaced every single piece of it — every plank, every nail — is it still the same ship? If it isn’t, at what point did it become a different ship? And if you took all the old pieces and moved down the port and reassembled them, is that still the same ship?” says Klenk.

“We wrestled with the question of identity over time. As a confused, aimless 19-year-old, it just blew me away. I thought, ‘You can study material like this and ponder these kinds of concepts?’”

“We wrestled with the question of identity over time. As a confused, aimless 19-year-old, it just blew me away. I thought, ‘You can study material like this and ponder these kinds of concepts?’”

Philosophy professors insisted on essays that were thought out and well constructed, improving his writing, he says. “It truly did teach me how to make an argument.”

He applied that skill as a proposal writer for ClearBridge Investments, an asset management firm based in New York with several offices around the world.

Organizations with capital to invest would put out a request for proposal (RFP) to several asset management firms, and Klenk’s job was to answer dozens to hundreds of questions in 100 to 200 pages and create a compelling PowerPoint presentation to earn the business. “I’ve helped secure wins in the eight- to nine-figure range,” he says.

Klenk, who earned an MBA in 2021 at Baruch College in the City University of New York system, has risen at ClearBridge to vice president, channel marketing and advertising. He is grateful to Glezakos for inspiring him to take the philosophy route.

OUTSTANDING LEADERSHIP

Glezakos says the past chairs for whom she worked, including Lee and Kennedy, created an environment that helped the philosophy department flourish and retain faculty.

“I just started as chair, but everything that we’ve become — a lot of it is due to past chairs, … the kind of climate they developed and the ways that they supported faculty and students,” says Glezakos. “They’re both genuinely modest. They offered guidance, but it was never about putting themselves in front.”

Kennedy, she says, is soft-spoken and clear-minded, and he inspired trust in his judgment. One of Lee’s many strengths, she says, is bringing a cheerful, positive energy — as well as snacks and drinks — to meetings. “He gives this feeling of ‘We are a community, and it’s fun to be a part of it.’”

Boomerang Nebula

CONNECTING WITH OTHERS

Lee was someone who made a huge impact on Jason LeVasseur (’94).

Jason LeVasseur

LeVasseur distinctly remembers not knowing how to deal with a breakup during college. “I thought I was the most heartbroken person in history. Romeo had nothing on me,” he says.

Instead of asking for advice from his peers, who might not have understood, he knocked on Lee’s door and was immediately welcomed. “I got to vent and say things that I couldn’t say to other people. Dr. Lee asked me thoughtful questions about my motives and did I want to get back together and was this the right fit for me. He helped me feel good about me. And he asked me questions about how I thought she felt, which helped me see things from her perspective,” LeVasseur says.

Lee’s generosity made the conversation one of LeVasseur’s fondest college memories. “I never felt like he was in a hurry. He made time and space for me. My biggest takeaway from that experience was: The philosophy faculty really, truly care about their students,” he says.

LeVasseur, a double major in philosophy and English, took that memory with him as he launched his career. His initial plan was to teach English for a few years, then go to law school and focus on environmental law, but music lured him away. A presidential scholar, LeVasseur joined a band called “Life In General” and began performing at venues and writing songs.

“Majoring in philosophy and having the ability to see things from different perspectives helped my songwriting. The words I would sing weren’t necessarily my story. I was able to write songs in somebody else’s voice,” he says.

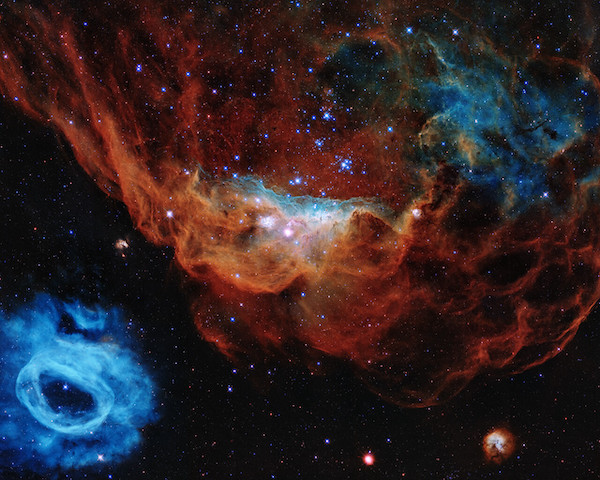

Stellar nursery with a giant nebula and its neighbor

During summers, he’d take a break from touring to work at a summer camp in Maine. An adviser from Central Connecticut State University visited the camp and walked in on LeVasseur leading a fun, inspiring staff training event and persuaded him to do a workshop with her college students.

“It was the first time I was on stage without a guitar or drums,” he says. That keynote address was such a success that it drove him toward another career: motivational speaking. He went on to create The Rock Star Project,® a leadership development program infused with his passion, music.

“I help celebrate your ‘instrument’ (the skills and strengths that make you unique) and how you make an impact on your ‘band’ (your team, your club, your family or your professional organization). I help students who don’t feel like they’re influential realize that they’re powerful. Part of being a rock star is embracing that your instrument matters,” he says.

He credits his positive, well-received talks to the bond that he experienced roughly 30 years ago with Lee. Now he’s paying it forward. He says: “I think I have a way of helping people feel comfortable. I can break down the wall or the barrier and help people feel connected to me.”

A SENSE OF COMMUNITY

Glezakos says the department’s professors make studying philosophy a good experience for students, even in a time when expressing themselves can be stressful in contentious discussions. Professors emphasize “fostering a climate that is supportive of dialogue,” says Glezakos. “(Students) can be questioned and challenged, but we do our best to not have an environment where people feel judged or shamed.”

The department has moved toward offering classes “with issues and concerns that students have and really giving them a setting to think carefully, slowly and intensely about these things,” says Glezakos.

“Young people right now have so much to contend with that feels important: social issues like historical and ongoing racism and its effects, environmental issues, political instability. Students are, like, ‘A lot is at stake, and we’re the people who are going to have to address these things. We’re going to have to find ways to work cooperatively with

people — maybe with people whose views are not the same.’”

That is the gift that philosophy professors aim to give to students.

Jane Bianchi (’05) became associate director of strategic communications and marketing for Berkeley Preparatory School in Tampa, Florida, in July. Previously, she wrote and edited for magazines and worked as a freelance writer.

But nature flies from the infinite; for the infinite is imperfect, and nature always seeks an end."

Above: Carina Nebula

Photo credits:

Tarantula Nebula: NASA, European Space Agency, Canadian Space Agency, Space Telescope Science Institute, Webb Early Release Observations Production Team

Messier 82 starburst galaxy: NASA, European Space Agency, Canadian Space Agency and Hubble Heritage Team at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI)/Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy from J. Gallagher of the University of Wisconsin, M. Mountain of STScI and

P. Puxley of the National Science Foundation

Tarantula Nebula closeup: NASA, European Space Agency

Helix Nebula: NASA, European Space Agency, C.R. O’Dell of Vanderbilt University and M. Meixner, P. McCullough and G. Bacon of the Space Telescope Science Institute

Lagoon Nebula: NASA, European Space Agency, the Space Telescope Science Institute

The Snake: NASA, California Institute of Technology, Sean Carey of the SNIC (Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing) Science Cloud, Spitzer Space Telescope

Pismis 24 star cluster: NASA, European Space Agency (ESA) and Jesús Maíz Apellániz of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Spain, with Davide De Martin of ESA/Hubble

Witch’s Broom Nebula: NASA, European Space Agency, The Hubble Heritage Team

A celestial cloudscape: European Space Agency/Hubble Telescope, NASA, J. Bally with

M.H. Özsaraç

Crab Nebula: NASA, ESA, G. Dubner (IAFE, CONICET-University of Buenos Aires) et al.; A. Loll et al.; T. Temim et al.; F. Seward et al.; VLA/NRAO/AUI/NSF; Chandra/CXC; Spitzer/JPL-Caltech; XMM-Newton/ESA; and Hubble/STScI

Whirlpool Galaxy: NASA, European Space Agency, S. Beckwith of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), The Hubble Heritage Team at STScI/Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy

Boomerang Nebula: NASA, European Space Agency, The Hubble Heritage Team (Space Telescope Science Institute/Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy

Stellar nursery with a giant nebula and its neighbor: NASA, European Space Agency, Space Telescope Science Institute

Carina Nebula: NASA, European Space Agency, Canadian Space Agency, Space Telescope Science Institute