Walk into Ben Farmer’s law office — with its crystal chandeliers, decorative molding, oil paintings, ceiling murals, custom wall coverings, Italian marble floors inlaid with oak strips and 19th-century hand-carved wooden furniture from Ireland — and you might think you’ve wandered back in time to a British barrister’s manor home.

It’s not your typical lawyer’s office. That would be correct, says Farmer (JD ’70), with considerable understatement, as he shows me around half a dozen sumptuously appointed rooms. Even the bathroom, with its hand-painted door and red wallpaper, is worth a stop. There’s not a computer in sight. (Computers for Farmer and his assistant are in two back offices.)

Farmer, 77, looks surprised when I ask him the obvious question: Why did he decorate his office in such opulence? “No one’s ever asked me that before,” he says. It all goes back to his childhood, when he learned to appreciate antiques, fine design and designers, he says.

It’s also about his love of history and, of course, there’s a practical aspect, too: “If you have to work, you might as well work in beautiful surroundings and surround yourself with beautiful things.”

The wall coverings in one room are real leaves, dried and glued to backing.

He bought most of the antiques during a treasure hunt in Ireland with his friend, designer John May, during the mid-1980s when he built his office. “Feel that,” he tells me, pointing to a cushion on a handmade chair beside a huge 1799 cabinet from Ireland. “That’s horsehair.”

His small two-story office looks more like a cottage, largely hidden behind a white-picket fence and trees and shrubs along a busy two-lane road in the small town of Jamestown, North Carolina, about 30 miles from Winston-Salem.

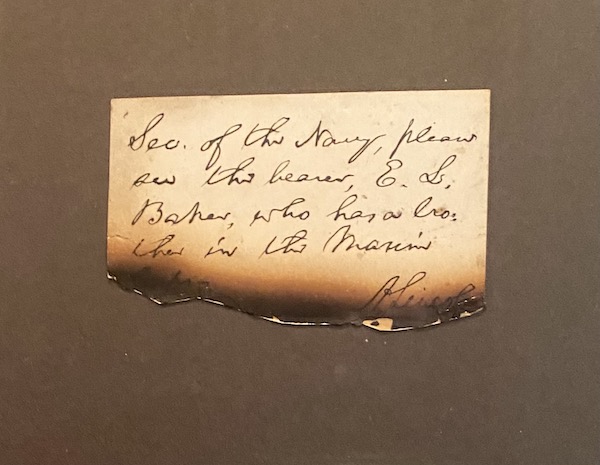

In more recent years, he’s collected dozens of autographs of authors, musicians and historical figures, including Abraham Lincoln’s signature on a fire-singed piece of paper, and historical documents dating to the 1700s.

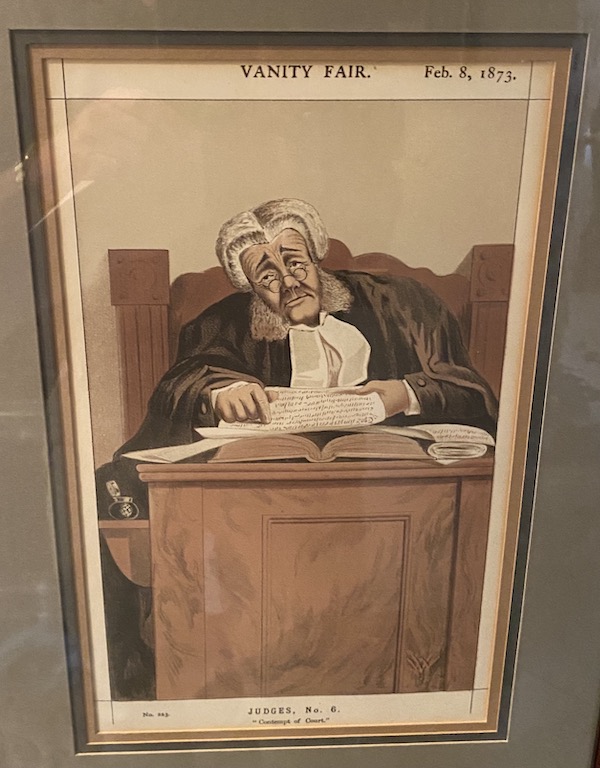

Appropriate for an attorney, he’s also collected more than 100 lithographs of caricatures of judges and barristers printed in the British magazine Vanity Fair from the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

Lincoln's note reads: "Sec. of the Navy, please see the bearer, E.L. Baker, who has a bro. in the Marines."

We finish our tour in a conference room with green-striped wallpaper, a crystal chandelier and doors brought back from Ireland; designer May found the artist to paint the nature scene on the door. The ceiling seems to disappear, thanks to a mural of a trellis covered in wisteria vines against a blue sky.

It’s hard to miss a large throne chair, with faces carved into the arms and legs, from the 19th or early 20th centuries, that Farmer purchased in an online auction. “I saw it and I liked it,” he says simply.

When I jokingly suggest that he pose for a photograph sitting on the throne, he proves to be a good sport. “Let’s do it,” he says. He runs into another room to grab a scepter, a red beret and a black cape with a red lining to put over his red shirt and black pants.

He wore the cape to get students’ attention when he taught a class to paralegal students at nearby Guilford Technical Community College. It worked, he says, and he was named outstanding teacher of the semester.

Farmer grew up in nearby High Point, North Carolina. His father restored high-end antiques for interior designer Otto Zenke, who designed and decorated mansions along the East Coast in the mid-1900s.

Zenke, a graduate of the Parsons School of Design, had studios in London and Palm Beach, Florida, but his main studio was in Greensboro, North Carolina. Farmer and his father often visited Zenke’s home.

After graduating from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Farmer came to Wake Forest for law school. He shares stories of professors Hugh Divine, Henry Lauerman and James Webster (’49, JD ’51, P ’81); parties at Reynolda Gardens and the Graylyn estate; watching Deacon golfing great Leonard Thompson (’70, P ’93) hit buckets of golf balls at a time; and working in the art gallery at Salem College, where he was exposed to more fine art.

He entered the U.S. Army — he received a draft deferment as long as he was in school — after finishing law school. He’s firmly convinced that it was his Wake Forest law degree that landed him a coveted spot in the judge advocate general’s office at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, instead of the rice paddies and jungles of South Vietnam.

After leaving the Army, he practiced law in High Point before moving to Jamestown. He is a former litigator who does mostly contract and estate work today.

When he was looking for a spot for a new office in the mid-1980s, Farmer and his business partner bought the 1834-44 William Reece House — once a stopover on the stagecoach line between Charlotte and Goldsboro, North Carolina — and the surrounding property on Main Street in Jamestown.

Ben Farmer's law office in Jamestown, North Carolina.

They restored the Reece House and built two cottage-like offices on either side; one houses Farmer’s law office. The exterior of the office is a visual treat in itself with a copper roof, red wood siding, a cast iron staircase and a postage box from Ireland from the Queen Victoria era.

Farmer turned to his friend and designer John May to design and decorate the office. They spent several weeks in Ireland finding antiques for the office. Farmer insists he was just the van driver on the trip; he trusted May to buy quality antiques and figure out where they would fit, such as the huge lead glass window from an Irish factory that became an interior wall in the office.

May selected the stunning wall coverings from a New York studio. The walls in one room are covered with real leaves, dried and glued to backing.

Abraham Lincoln's signature and an 1896 letter signed by Lawrence Weldon, an Illinois attorney, politician and friend of Lincoln's.

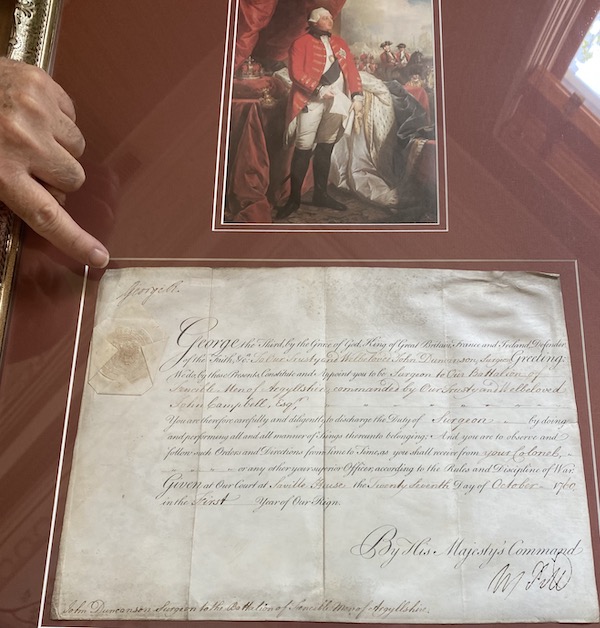

As beautiful as his office is, Farmer is more eager to talk about some of his collections. “Let me tell you a story,” he says frequently, as he shows me the piece of paper signed by Lincoln, an 1899 typed letter from Lincoln’s oldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, and a 1760 document from King George III.

The latter is beautifully written, if a bit difficult for 21st-century readers to decipher, but you can clearly read “George the Third, by the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith.”

1760 document from King George III

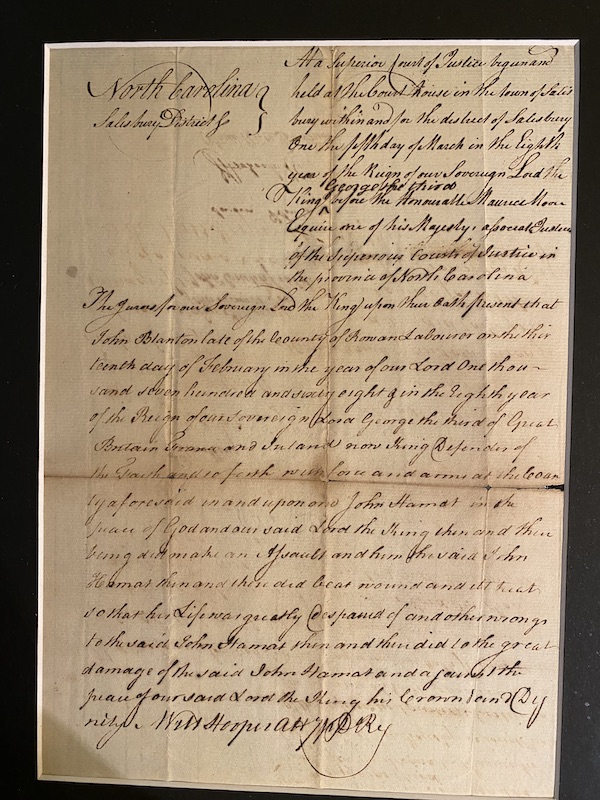

One of Farmer’s favorite items is a 1768 legal document signed by William Hooper, one of three North Carolinians who signed the Declaration of Independence. Hooper doesn’t get the attention that he should, Farmer says.

Hooper was strongly loyal to the British crown before changing allegiances and predicting that the American colonies would build a nation upon the ruins of Great Britain. (Hooper was still loyal to the crown when he wrote the document in the “Eighth year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord George the Third.”)

1768 legal document signed by William Hooper

Alongside the historical documents, dozens of framed Vanity Fair caricatures line the hallway in Farmer’s office. The magazine, published from 1868 to 1914, was known for its full-page color caricatures of well-known people.

Farmer shows me his favorite: an 1897 caricature of barrister Henry Fielding Dickens, son of author Charles Dickens. He loves the caption under Dickens’ caricature: “His father invented Pickwick.”

He points out the artist’s signature on many of the caricatures: “Spy,” a pseudonym for British artist Sir Leslie Matthew Ward, who painted more than 1,300 caricatures for Vanity Fair.

Vanity Fair lithograph from 1873

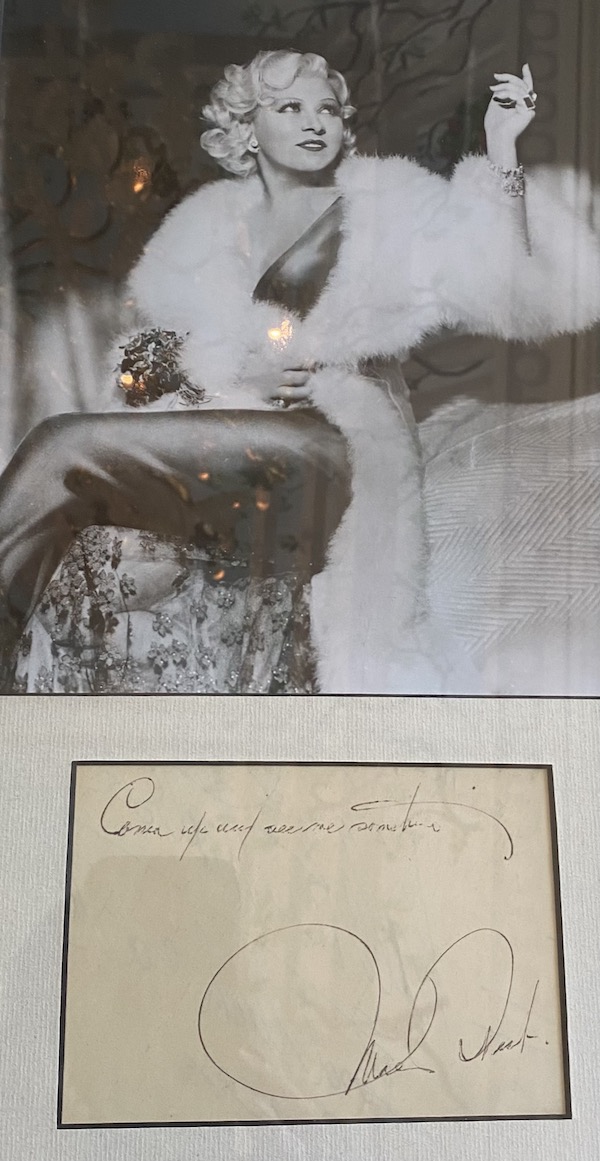

Under the blue-sky trellis mural, a conference table is piled high with framed autographs and photographs that Farmer has collected. He tells a story about each as he shows me autographs of composer Irving Berlin, author O. Henry (William O’Henry Porter), boxer Muhammad Ali (who also signed his birth name, Cassius Clay), actress Mae West and playwright Tennessee Williams.

He’s especially proud of an autograph of musician Count Basie. He purchased his other autographs online, but he got this one himself when he was a high school band student and met Basie backstage at a concert in Greensboro.

It’s not the person’s signature that’s important to him; it’s the significance of who the person was. “Sit down. This may take a while,” he suggests, as he shares more stories.

Mae West autograph with her famous line, "Come up and see me sometime."

Farmer has more “stuff” in his home and a second house that he also owns. He bought his home, the historic Jeduthun Harper house (circa 1815), in Trinity, North Carolina, from May when the interior designer moved to Charleston, South Carolina.

As I leave Farmer’s office, I ask him what’s next? He’s following several items on online auctions, he admits. Stay tuned. There’s literally more to come.

Even the bathroom in Ben Farmer's office is a visual delight.