Caitlin Berry ('09). Top photo, Kehinde Wiley's "Sleep" and El Anatsui's "Man's Cloth" were in the group show that opened the Rubell Museum DC in August. Museum photos courtesy of the museum.

Caitlin Berry (’09) has been especially busy in the past year.

She and her husband, Kyle Walden, welcomed their baby girl, Rosie, in December. That was just two months after Berry welcomed guests at the October opening of the new Rubell Museum DC, where she assumed the role of inaugural director in August.

The museum rose from the ruins of a segregated Black junior high school in Southwest Washington, D.C. Don and Mera Rubell and their son, Jason, bought the historic 1906 building and transformed it into a second location for exhibiting their formidable modern art collection.

The Rubells have showcased their works — more than 7,200 by 1,000 artists such as Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman and Jean-Michel Basquiat — in Miami since the 1990s and opened a museum there in 2019. The couple, who began collecting art in 1964, have said they chose the Washington neighborhood as a place to enlarge public access to art with a cultural, community focus in the nation’s capital, a city of political and social power.

Berry says leading the museum is a dream job. She has honed her skills from her beginnings at Wake Forest as the first manager of the stArt Gallery for student work, to working in galleries in New York and Washington, to representing artists as a dealer, to directing the art museum at Marymount University. She says running the nonprofit Rubell Museum DC is about making people feel special, whether they are artists or community members. “I want to create this environment where people feel seen,” Berry says.

Managing Editor Carol L. Hanner talked with Berry about her work and her life. Excerpts from the conversation have been edited for clarity and brevity.

CH: What drew you to Wake Forest?

CB: I grew up in Winston-Salem, … really straight through the neighborhood public schools. My father (Joel Lyman Berry, Ph.D. ’00, P ’09) actually taught at Wake Forest in bioengineering. … I knew how rigorous Wake Forest was academically. It was a great fit. I applied early decision. I applied to one school; it was Wake Forest, got in, and that was it. I never looked back.

CH: Did you know that art management was in your future? (Berry majored in communication with a minor in studio art.)

CB: The short answer is no. I had no idea I would end up doing what I’m doing now. … I always loved fashion and style and worked in retail environments. … But when I … started taking communications classes, I realized that this was an area in which I excelled and thought maybe PR or advertising would be for me.

But my whole childhood, I was making art and always took art classes and felt most at home in those environments. … I knew I didn’t have the talent to make a career of my own artistic abilities, but while I was in school, I always worked (in a cosmetics store in high school, a jewelry store in college). My dad made a deal with me: “Whatever you make this summer, I will match it, and you can put that toward your first car.” I worked on commission, … and I think the number truly shocked him.

I realized I had a knack for sales, a knack for communication, and I loved art. So, it was, “How do I put all these things together?” And that’s how this management and the visual arts course came into play to pull all of those things into a field that I didn’t really even know existed.

CH: What is it about this particular work that makes you happy?

CB: I believe in the power of art to reflect back on society, where we are at any given moment in time and that that sort of mirroring in life and in culture is very important. I also feel like that reflection is important in conversation when you relate to other people, which boils down to what is essentially empathy, right?

CH: Describe how you work with artists.

CB: (Berry describes a Wake Forest friend who works at Amazon as a liaison translating between product users and coding engineers who speak in technical language.) In a weird way, I feel like I do that in the art world. I can get in a studio with an artist, talk to them about their process, what their vision is and package that and make it attractive and understandable for a potential collector. Now, I’m doing this in this nonprofit museum space where it’s not so much about acquisition, it’s about connection.

Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77) said, “People won’t remember what you said, but they’ll remember how you made them feel.” I bring all that into what I do on a day-to-day basis and try to create the most positive, easy, natural, encouraging special environment that I possibly can for them.

CH: What did you learn as the founding manager of Wake Forest’s stArt Gallery for student work, in your post-graduate fellowship?

CB: It was foundational to my growth as a professional and laid the groundwork for me to understand at a very basic level what it’s like to run a small business and have many different missions and visions and try to articulate them all.

There was the educational focus in creating a gallery that could be a workshop for students to figure out, “… How do I then interface with a gallery who might be able to sell it?” …

And our programming to encourage other students to come visit. And the community and looking at numbers, budgeting, operational logistics, you name it, we all had to figure it out together. It was very much a collaboration between myself, (director of art galleries and programming) Paul Bright (P ’12), (business associate professor) Gordon McCray (’85) and the (former) provost (Jill M. Tiefenthaler).

CH: What was surprising about your stArt Gallery experience?

What surprised me (was) how much it intensified my desire to do that for a living. I couldn’t wait to get to New York. I had been there the summer prior (as an intern) and worked for (gallery owner) Cristin Tierney (’93). She’s the fairy godmother of the Wake Forest art world and has been a major influence on most art alumni who decide to enter the art market.

It was that experience that I think made me an attractive candidate to the galleries I was applying to back in New York.

Berry in the stArt Gallery in 2009, when she was the founding manager who helped set up the Reynolda Village space for showing student work.

CH: What was your next position?

CB: The next position was as the gallery manager at Eykyn Maclean, which was a small, private gallery on the Upper East Side run by (Christopher Eykyn and Nicholas Maclean) who used to run the Impressionist and Modern department at Christie’s (auction house). But also we were doing these crazy blockbuster exhibitions, and I was entrusted with a lot of responsibility at a very young age. That was really baptism by fire. It was the most fun.

CH: What was one of your most memorable moments from that time?

My bosses traveled all over the world for different auctions and exhibition openings. One day I happened to be the only person at the gallery, and a very well-known collector called. I answered the phone. We were doing an exhibition of Andy Warhol’s flowers, large works on canvas. And he said, “I understand that you have this particular painting. Could you bring it to my house … tomorrow?” In the art world, moving a $10 million work of art in a matter of hours is very logistically challenging.

So, I said, “Of course, yes, no problem,” and then hung up the phone and screamed and panicked and called my bosses and, like, how do we make this work? I was able to find a truck and art handlers to help me take it over there. …

We got up to his penthouse, and. … we were making small talk. He looked at me and said, “What does it look like?” And I thought, “What does he mean?” If I had done my homework, I would’ve known that this collector didn’t have access to his entire visual scope.

In the moment I had to rely on, “OK, four flowers, green, pink, blue, the intensity of the color is more muted in this area of the canvas.” He had all the art historical knowledge of what these flowers meant to Andy Warhol’s career, but he wanted me to just describe it.

I took that lesson with me throughout the rest of my career. A lot of the time, the most accessible way to talk about art isn’t to give all of this deep, theoretical, ivory tower sort of description of the work. It’s to meet people where they are and just talk about what you see on a canvas.

CH: What brought you to Washington, D.C.?

CB: This is kind of the tale as old as time. My husband — he was my boyfriend at the time — he’s worked in the defense side of government. I loved New York but was young and thought, Washington, why not? Yeah. Let’s do it.

CH: What were your moves in D.C.?

CB: The first job I landed in (2013) was this small gallery (of 19th-century art) and then hopped over to what became one of the most formative experiences of my life (at) Hemphill gallery. George Hemphill, the owner, has been in business for (more than) 25 years. … I learned so much from him about the Washington Color School (of abstract expressionist art), how this was the nexus of creativity on the East Coast in the late ’60s and what a unique voice Washington artists have in the scope of art history.

I was also working with contemporary artists, which was very new for me because all of the artists whose work I was dealing with prior to that were dead, so I couldn’t ask them any questions about their work. (She laughs.) In this instance, I was able to walk into their studios and hear what they had to say and ask them about their lives and what brought them to use this kind of material. I enjoyed every minute.

After that, I left to found my own art advisory (company) and worked with clients all over the country and during COVID started working with artists because the playing field was leveled for galleries because nobody could go see art in person. I ended up launching a series of these virtual galleries … for each artist. I had a great amount of success with that venture.

And then, because I can’t ever work enough, I decided to get into the educational space once again and curate exhibitions for Marymount University’s Cody Gallery as their director.

CH: How did the pandemic affect people in the art world?

CB: In the beginning, March, April, May (2020) was really, really scary for anyone in business in the art world or maybe in business at all. When my industry realized that the pivot online was relatively easy and actually kind of exciting, everything just picked back up. I’d never been busier. My colleagues reported unreal sales during 2020, 2021, 2022.

People still want to see art. They still want to talk about art even if it’s not in person. We had all this time on our hands all of a sudden, so, yeah, it was an opportunity. I will say this: It was very, very, very, very hard for most people. I was in a privileged position to be able to pivot, (as were) a lot of collectors who have the disposable income to buy art.

CH: How did you connect with the Rubell Museum DC?

CB: An artist I had worked with … texted me one day. I was actually at Wake Forest for an arts event. She said, “Do you want to be a museum director?” And I said, “Well, sure, but what are you talking about?” When she told me it was Mera Rubell (to discuss the DC museum project), she said, “Would you want to talk to her?”

(The answer was, of course yes.) I got on the phone with Mera and her husband, Don, when I was in Winston-Salem, and we had a wonderful conversation. To hear Mera and Don and their son, Jason, … talk about the way they think about work, artwork and how they talk to artists and their collection, and just this history of their family, it’s such a privilege to be a part of that. I’m just loving it, loving working with them.

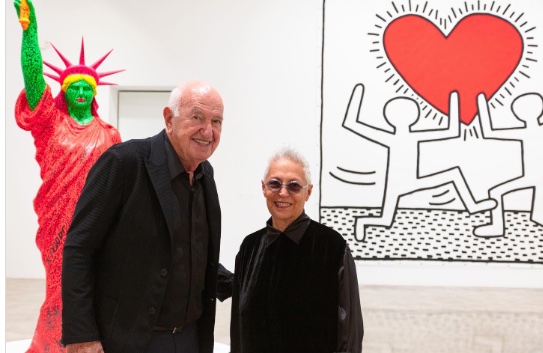

Art collectors Don and Mera Rubell. Don Rubell told The Washington Post in 2022: “Contemporary art is a catalyst for serious conversation.” He said that artists don’t shy from complex issues such as race, immigration, violence and identity, so what better place than in the shadow of the Capitol could the couple have chosen for a second museum to generate conversations around art? The couple built the Rubell Museum DC on the site of an abandoned former junior high school for Black students that closed in 1978.

CH: You had this big museum preparing to open and you were pregnant with your first child. What a big time for you.

CB: I spoke to Mera and Don on a Friday and found out I was pregnant on a Saturday. It was “Oh, my gosh.” I thought, well, neither one of these is necessarily a guarantee. I’m going to proceed and see what happens. And both of them ended up becoming viable paths forward.

For any woman in the workforce, one really has to ask themselves: Can I do this? Do I want to do this? Is this practical for me to balance these two life-changing things? And I thought, “Hell, yeah. I mean, of course, I can do both.” I’m walking in the footsteps of women like my mother, my grandmothers who worked really hard for me to have this opportunity. …

The Rubells … have been so supportive of me as a director, of me as a mother, and I’m getting to do both of the things that I love and am passionate about. And I’m really, really grateful for that.

CH: What were the highlights for you of the museum opening?

CB: Of the first five people in line, there was a group of three women who were graduates of Randall Junior High School. And they had their yearbooks and report cards from their time. The school closed in ’78, and so they were some of the last graduates.

To meet them and … to hear them say, “I never thought I’d walk in here and see artwork on the walls that are representative of me and who look like me by artists who look like me.” That was the highlight, absolutely.

A woman at the opening of the Rubell Museum DC holds her copy of her 1962 yearbook from Randall Junior High School, a segregated school for Black students that was closed in 1978. The building was remodeled from disrepair to become the Rubell Museum.

Singer and Motown icon Marvin Gaye was a graduate of Randall Junior High School in the mid-'50s. … We had a wonderful suite of Keith Haring works on paper (for the Rubell Museum DC opening). … In the notes Haring talks about having listened to Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” (also the name of the museum’s opening show) for the first two hours he was making the work. To be able to show that in this space was really special.

CH: What are your priorities for the museum?

CB: My first priority is creating programming for our community and our membership that pulls in the history of this place with the artists and the artwork we are showing here, … creating the opportunity for people from all walks of life, from different industries in Washington to be able to come here and have unique reactions and unique conversations around the artwork.

CH: How do you learn about this huge family collection?

CB: (She describes the great knowledge shared by the staff at the Miami museum and their collaborative approach.)

There’s no shortcut. I’m learning this collection one artwork, one artist at a time. … You can’t know everything about art, you just can’t. So, I learn something new every day, and, and that’s why I love what I do.