The Great South Window in Canterbury Cathedral. Top image, stained glass panel depicting Nathan, an ancestor of Christ. Photos of Canterbury from the cathedral and Bridgeman Images.

ithin the majestic stained glass windows of England’s celebrated Canterbury Cathedral, a lost secret of medieval history hung in plain view for more than eight centuries.

ithin the majestic stained glass windows of England’s celebrated Canterbury Cathedral, a lost secret of medieval history hung in plain view for more than eight centuries.

In 1987, an art historian with a sharp eye and deep knowledge had posited the secret, but her theory about the Ancestors of Christ window series gained little traction without hard evidence. It was not until 2020 that Laura Ware Adlington (’10) created an innovative process to help solve the mystery scientifically, using chemistry, math and an adaptation of a handheld device that looks like a space gun.

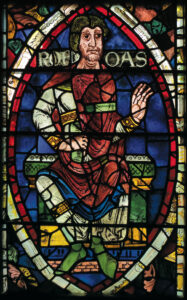

The secret? The glass in a window panel depicting Nathan, an ancestor of Christ, is much older than experts had believed. The art historian had proposed that Nathan dates to 1130 to 1160, and Adlington’s chemical analysis supports that theory. This appears to make the panel the oldest figurative stained glass window still in place in the United Kingdom — and among the oldest in the world.

Nathan’s panel contains glass older than most of the other windows in the Ancestors of Christ series, which depicts the genealogy of Jesus from Adam to the Virgin Mary. The windows were installed to replace those lost in the cathedral’s catastrophic fire in 1174. The estimated age of Nathan’s window means it predates the fire — as do possibly three other as-yet untested windows with the same stylistic differences noted decades ago by the art historian.

Laura Ware Adlington (’10) at her home in Pennsylvania. / Photo by Dave Moser

dlington’s post-doctoral work supports the art historian’s conclusion that monks salvaged Nathan and the three similar windows from the ashes until the sacred images could be restored to their proper place of glory.

dlington’s post-doctoral work supports the art historian’s conclusion that monks salvaged Nathan and the three similar windows from the ashes until the sacred images could be restored to their proper place of glory.

Full panel of Nathan in Canterbury Cathedral

The discovery has excited historians’ imaginations. It would mean that the assassination of Archbishop Thomas Becket on Dec. 29, 1170, unfolded under Nathan’s gaze. On that infamous day, four knights of King Henry II unsheathed their swords to murder the king’s nemesis. They chased the archbishop to the altar, acting on the monarch’s angry admonition that his court should not let him “be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric!”

The spilling of Becket’s blood on the ornate floor, in front of stunned worshippers at this English center of Christian power, set off political and religious turmoil across the kingdom and made Becket a martyred saint three years later by papal decree.

Besides enlivening history and resolving the mystery of the mismatched Canterbury panels, Adlington’s innovations have opened new windows to previously inaccessible investigations of stained glass history. Her work has blown fresh breath into interdisciplinary collaborations among scientists, art historians and conservators, whose concerns have sometimes collided, say colleagues and experts.

Stained glass depicting martyred Canterbury Archbishop Thomas Becket, made by Samuel Caldwell Jr. in the early 20th century using a few medieval fragments.

Adlington’s achievement was to adapt a handheld spectrometer that aims X-rays at glass or other material and measures the elements inside. The spectrometer does this in a non-invasive way, without the need to risk disassembling windows or chipping off samples for a lab analysis. She invented a simple but critically important, 3D-printed plastic device that attaches to the spectrometer with Velcro. She gave the attachment a cheeky name, the Windowlyzer. It allows measurements with previously impossible precision for testing glass panels that are still installed in a building, or in-situ.

Adlington, 35, is low-key and humble about confirming the art historian’s theory that was published the year Adlington was born. But Leonie Seliger, Canterbury’s stained glass conservator, says Adlington’s creative approach was inspiring. It “really, really is a game-changer.”

A Classic Deacon

That Adlington chose Wake Forest for undergraduate studies is no mystery. Her family is filled with Deacons: her parents, Rick Ware (’72) and Debbie Darden Ware (’75), who met at Wake Forest; a brother, Don Ware (MBA ’12); her late grandfather, Jim Darden Jr. (’45, MD ’47); her uncle, Jimmy Darden III (’81, P ’16), and two aunts, Sally Ware Mims (’83) and Charlotte Darden Miller (’79) and Charlotte’s husband, Dr. Mill Wayne Miller (’80). The family endowed the Ware Family Scholarship at Wake Forest.

Laura grew up going to tailgate parties and games and seeing her parents smile with old friends. “It was my ideal college,” Adlington says.

She arrived on campus certain she would major in physics and her mother’s major, mathematics. As so often happens with Wake Foresters, Laura’s horizons widened. “I started right in with physics courses, and I kind of fell in love with social studies along the way,” she says.

Growing up in Pennsylvania, she was so enamored of Latin in her high school classes that she chose it exclusively over modern languages. At Wake Forest, she ultimately majored in classics with minors in mathematics and anthropology. She studied abroad in Florence, Italy, and immersed herself in history, art and archaeology. Fittingly, she lives in a 17th-century renovated log cabin in Wayne, Pennsylvania, with her husband, Edward, who is a printmaker and an elementary school art teacher, and their son, Jonny, just shy of 2 years old.

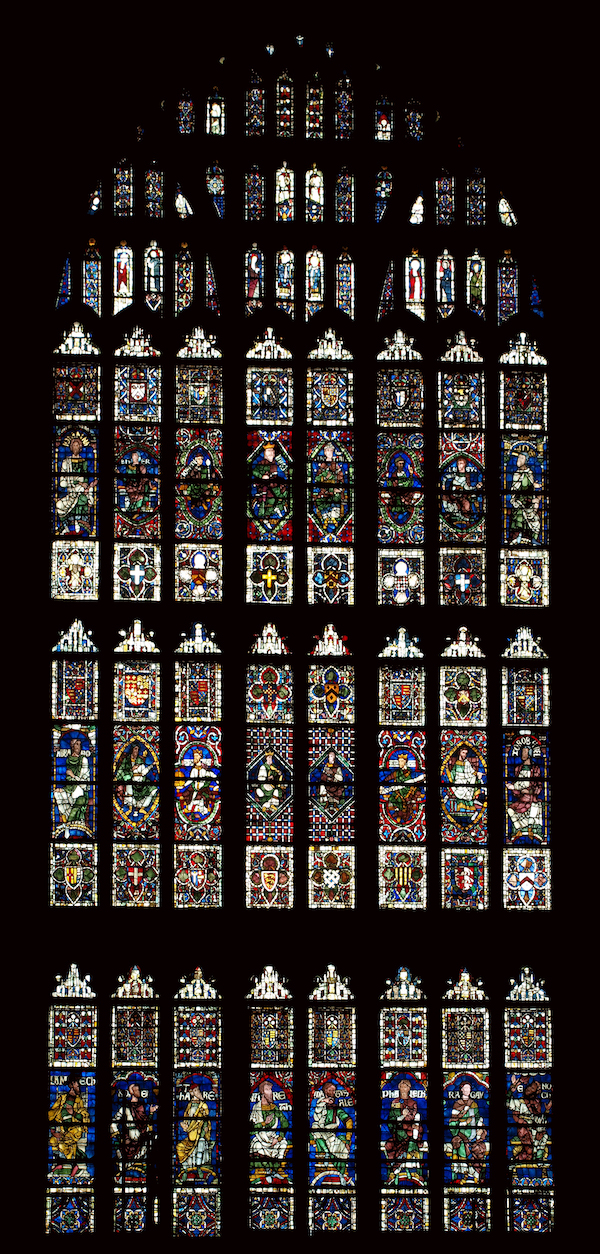

Canterbury Cathedral’s Great South Window contains some of the panels in the Ancestors of Christ series, including Nathan, with a red background, fourth from right in the top row of the largest panels. Beside Nathan is the crowned King David, also with a red background. Chemical analysis supports the theory that Nathan dates to 1130 to 1160, earlier than believed, as is suspected of King David’s untested panel. Two other untested panels believed to be made in the same earlier period hang in the Great West Window.<br />

“It’s just so finely, beautifully painted in such minute detail. They labored over this, and most people are going to be quite far away from it and not be able to see such amazing details.”

The Road to Stained Glass

How did Adlington land in the world of stained glass archaeology? “I kind of fell into it,” she says. “Like early adulthood, I just kept following different opportunities, and I didn’t really have a plan.”

She credits her adviser, Tom Phillips (’74, MA ’78, P ’06), with the prescient suggestion that he could see her in art conservation one day. It was Paul Thacker, an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at Wake Forest and director of the University’s Archaeology Laboratory, who urged her to apply for the Richter Scholarship Program. That led her to Italy for a summer dig studying Etruscan culture, which bridged ancient Greek and Roman cultures. The women of Tuscany held an unusually elevated place in male-dominated Roman society. The topic became her senior thesis and lured her into archaeology.

“I’ve always loved history,” she says. “I always really loved the mythic stories and Homer, … these older expressions of ourselves as humans and how much they still resonate today.”

When the time came to look for a job, Adlington reached out to the editor who curated a favorite book on Etruscan women, and the connection led to an internship at the British Museum in London. Adlington learned about a master’s program at University College London to specialize in scientific archaeology or archaeological science.

Canterbury Cathedral

The program aims to bring humanities students into science, and “you don’t get any more humanities than the classics,” says Adlington’s UCL adviser, Ian Freestone, a professor of archaeological materials and technology who drew her into the post-doctoral Canterbury work. Initially, he wondered whether Adlington’s classics focus would challenge her in a scientific program, but “it turned out she was a natural as far as applying the science was concerned.”

In fact, merging her love of science with her fascination with cultural history was just what Adlington craved. She began pursuing her Master of Science in the Technology and Analysis of Archaeological Materials.

She was drawn to stained glass more than ceramics or metals as her material of choice. Glass played to her strengths and her desire for certainty in results, she says.

“You analyze it. You get a list of numbers of its composition, and you can apply statistics to it. It’s just really straightforward to me in the information you can pull from it. … Of course, it’s a bit more complicated than that,” she says.

A 13th-century stained glass panel in Canterbury Cathedral depicting Samson and Delilah

The beauty of the work also drew her in, she says. She felt privileged to see the glass up close. “It’s just so finely, beautifully painted in such minute detail. They labored over this, and most people are going to be quite far away from it and not be able to see such amazing details.”

Freestone pulled her into a conservation project at York Minster, one of the world’s great cathedrals. The work in York became her master’s thesis, which received the highest mark among the program’s 272 students in 2013 and won an Institute of Archaeology Master’s Prize.

She extended her work at York to earn her UCL doctorate in archaeological materials science, which laid the foundation for her postdoctoral work at Canterbury Cathedral.

What Makes Stained Glass So Important

Pondering the great art of the world brings to mind the European Renaissance of the 14th to 17th centuries — Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael — rather than the Middle Ages preceding it. But stained glass is an art form with its own magnificence.

Stained glass brought light into the Dark Ages.

“The first words we hear come from the mouth of God in the Book of Genesis are ‘Let there be light,’ and Christ identified himself as the light of the world,” says Sarah Brown, director of the York Glaziers Trust at York Minster, where Adlington conducted her graduate work.

Theologians regarded light as the means for infusing God’s spirit into the church. The windows were a way to “bathe the devout, could transport you psychologically and in terms of your imagination and your senses,” Brown says. She has seen seasoned, modern travelers gasp as they step into the cathedral.

"These were cutting edge works of art. They were masters who grabbed the art of their time and shook it by the scruff of its neck.”

“The language in which the Book of Revelation describes the heavenly Jerusalem is comparable to what you would experience walking into a medieval cathedral, … the closest experience you can get to heaven on earth,” she says.

The chance to work at York Minster and then to do post-doctoral work at Canterbury Cathedral in Kent were huge opportunities for Adlington.

Canterbury, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was founded in 597 AD, establishing Christianity’s foothold in England. Besides its fame as the site of St. Thomas Becket’s murder, the cathedral is home to the Ancestors of Christ stained glass series, considered among the most famous works of medieval painting. Originally 86 windows, with 43 surviving, the series depicts the male ancestors of Christ in colored glass with the faces and clothing painted on the surface. The life-sized seated figures inspired awe and told visual stories to the many illiterate worshippers of medieval days.

Leonie Seliger, the Canterbury conservator, says the ancestor windows were as bold and fearless for their day as modern Abstract Expressionism was in the 1940s. “These were cutting edge works of art,” she says. “They were masters who grabbed the art of their time and shook it by the scruff of its neck.”

York Minster, the First Synchronicity

In just the first of several well-timed connections, Professor Freestone introduced his grad student Adlington to York Minster, which was engaged with York Glaziers Trust in one of the world’s largest and most complex conservation projects from 2005 to 2018, restoring its Great East Window. It is the largest medieval stained glass window in England and beloved for its beauty, sophistication and iconography.

In a shock to conservators in 2005, a piece of stonework around the window fell to the floor. Repair became mandatory, says Brown. Fixing the stonework required taking down the windows. Experts grappled with whether to simply fix the stonework and return the glass as it was or seize the chance to correct the many piecemeal restorations done through the centuries.

The risky decision was made: dismantle, repair and restore while staying true to the original design. The experts drew on the window’s extensively documented building contracts from the 1400s and discussed each tiny piece of glass to assess whether it should stay or go and whether to alter a panel in any way.

A detail from one of the late 12th-century Bible windows in Canterbury Cathedral depicting the Magi following the star toward the birthplace of Christ.

Conservation of medieval glass has changed over time, Adlington and Brown note. In earlier centuries, art and historical value played second fiddle to expedience and cost in patching up holes to keep worshippers secure from the weather. Some restorers were closer to plumbers than artisans, Brown says.

As the art of making medieval glass was lost, restorers often inserted 19th-century stained glass, with brighter but harsher colors, into medieval windows, creating noticeable mismatches. Then 20th-century conservators set out to remove this inserted 19th-century glass, sometimes with equally dismal results such as a head too big or too small for the figure. In the Great East Window, “we did have a small number of 1950s interventions which frankly were so gruesome that we didn’t retain them,” Brown says.

Pulling History from Medieval Glass

Adlington was not the first to use an X-ray spectrometer to assess the chemical makeup of materials. Stained glass researchers had used it to determine broadly a window’s era or whether windows, mostly post-medieval, were original to a home or church, Adlington says. She refined the process further to focus on medieval stained glass.

She analyzed just one panel at York for her master’s thesis, hoping to unpack glaziers’ methods and the craft of European studios from which English artisans imported their colored glass. The elements in glass differed by region, according to the sand, trees and plants found there.

“It was pretty surprising to us actually that we were able to detect (individual) batches … from the same glass house,” Adlington says. They could see distinct compositional differences between one sheet and another made just a short time later.

Traditionally, researchers take samples to characterize glass based on the lighter elements present, which make up the majority of glass. But the spectrometer had poorly analyzed those lighter elements when glass had decayed in the humidity or water seepage of England’s soggy weather. Adlington recalibrated the spectrometer to focus only on the heavier elements in glass that can identify its origins, yielding meaningful data.

Luckily for Adlington, York had dismantled the glass from its surrounding lead profiles, called cames, that hold each piece of glass in place. With the glass freed from its cames, researchers could do lab tests on discarded glass or on pieces sturdy enough to withstand having a tiny sample chipped off the side. Reinserting the glass into its cames would cover the surgical sampling scar.

“The risk of breaking the glass is there, but it’s a small risk,” Adlington says. Skilled conservators know what they’re doing, she says.

For her master’s research, Adlington benchmarked the spectrometer’s accuracy by comparing lab data for 30 samples of a single 4-foot panel against spectrometer data for 100 samples of the same panel. She was excited to learn that her results not only matched the trustworthy lab analysis but also aligned with the conclusions of the veteran experts who worked on it.

Brown says Adlington’s analysis helped York create new learning about the craftsmen’s methods, enlarging their story in history. It also formed the proof of concept for Adlington to apply for a larger sampling for her doctoral degree.

Brown says the project “demonstrated the power of interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary working. It really turns a whole page in terms of how we can all work together so profitably.”

“It’s not carbon dating (which works only for organic material.) It’s all the weight of the evidence. It’s circumstantial. … We are piecing together a mosaic."

Adlington and conservation manager Nick Teed of York Minster in 2016 examine a panel of stained glass whose pieces are dismantled during an ambitious restoration in the cathedral.

At Canterbury, Another Mishap

For Adlington, synchronicity continued. Falling stonework had set off the York restoration. Four years later and 4½ hours away, another surprising stonework freefall bedeviled Canterbury Cathedral.

“In 2009, our biggest window spat a surprise at us,” says Seliger, Canterbury’s conservator. The 60-foot-tall perpendicular Great South Window has many transoms and mullions, the vertical stonework that separates window units. “One day a large chunk of one of the major mullions ended up on the floor,” she says.

Inspectors scour the cathedral every five years, and it has an architect on site, but “this was a perfect storm of extremely hot summers and a leaking drain and an earthquake a few years before,” Seliger says.

Canterbury had to immediately install supporting scaffolding. “That window had to go into a corset,” she says. “We needed to evacuate the stained glass. You don’t leave that sort of important stained glass in a window that isn’t structurally sound.”

Seliger is director of Canterbury’s Stained Glass Workshop. It not only cares for the cathedral, which she says holds the best collection of early medieval glass outside France, but has resources to collaborate with other churches and museums to expand historical and technical knowledge.

A stained glass panel in Canterbury Cathedral shows English King Henry II visiting the cathedral tomb of St. Thomas Becket in 1174 in a public act of penance for the king’s soldiers assassinating Becket four years earlier. Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry’s ally-turned-nemesis, was slaughtered at the altar in front of worshippers. Henry took 300 lashes from the monks as penance, quelling unrest and giving his endorsement to the cult of pilgrims who sought miracles at the cathedral after Becket’s death.

As York Minster’s leaders had done, Canterbury’s experts had to decide how much restoration to undertake while the precious stained glass was out of the wall and accessible.

The stonework had been installed in the late 1700s to hold much older, medieval stained glass in very high windows. “They thought, ‘Hey, nobody sees it up there. Let’s just grab it from (another spot), stick it in the Great South Window … and we don’t have to pay for new stained glass,’” Seliger says.

“You have to imagine this window being the world’s craziest, most glorious and most expensive patchwork quilt. It’s full of really important medieval glass that doesn’t belong there.”

Ultimately, Canterbury chose massive restoration of the stonework only.

About the time the endangered panes moved into storage, Seliger heard from Professor Freestone about his hopes that he and his student Adlington could expand their research at York Minster into Canterbury.

“There was a certain amount of serendipity,” Freestone says. And with no pun intended, “Everything fell together just at the right time.”

Solving Canterbury’s Mystery

It was British-American art historian Madeline Caviness who wrote in 1987 about the stylistic differences that set apart four figures in Canterbury’s Ancestors of Christ panels.

Caviness, who retired from a distinguished career at Tufts University in Massachusetts, began her lifelong study of stained glass with a fortuitous purchase as a young woman. “I love stained glass. I think the colors are beautiful, … and I found some in an English antique store and bought it for a few shillings,” says Caviness, 85. “I took it to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which is kind enough to give you some advice about what you have.”

The answer? Her piece wasn’t worth much, but she learned that the last great stained glass expert in that department had died, with no real successor in England. She says many women of her generation hesitated to join a field crowded with men. “So it seemed like a perfect challenge for me to see if I could step in and begin to learn about glass,” she says.

She won a scholarship to learn with the best people in France, published an article and “got going along well with it.”

As she prepared a catalog for Canterbury in the 1980s, the dissonance she saw in the four ancestor portraits nagged at her. But a catalog is a reference work, she says. “You have to be very careful to be sure you proved everything. It’s not a place to publish risky theories or hypotheses.”

She held onto her hunch and published the theory elsewhere, first in 1987.

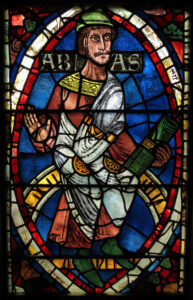

Her essay focused on the panels depicting King David; his son, Nathan, brother of King Solomon; Roboam, Solomon’s son; and Abia, Roboam’s son.

From top left clockwise, King David and Nathan are in the Great South Window, and Roboam and his son, Abia, (the spelling of their names varies in historical references) are in the Great West Window.

“The evidence I had in front of me was … the way the glass felt to my touch, the way the different glasses had weathered and broken down compared with other figures in the series, and largely the style, which is quintessentially Romanesque as opposed to beginning to look like early (Gothic) art,” she said.

The four figures were smaller and more squat than the others, perhaps indicating previous placement in a smaller frame. The folds of their robes, the size of their hands, their heavily drawn eyes and noses, their beards and other features differ from the surrounding ancestors but match the style of wall paintings from 1130 to 1160. Well-documented building records meshed with her theory, she says.

“The reason I could go out on a limb has to do with how art historians are trained as opposed to people in the sciences, and I think we need to work together,” Caviness says.

Her conclusion was that monks rescued the four figures after Canterbury’s 1174 fire. A historian of the time, Gervase of Canterbury, described grieving monks wailing and howling at the fire’s ravages in the sacred cathedral area he called “the glorious choir.” Caviness concluded that the four panels were repurposed during the restoration through the early 1200s.

Disaster with an Upside

Seliger had long known of Caviness’ theory but also knew that taking down the windows to investigate the theory was too dangerous for the historic stained glass — until the stonework disaster created a partial opening.

Seliger had admired Caviness’ chutzpah in publishing her theory and wondered if it could be confirmed.

“In 1987, making a stylistic analysis purely based on a person’s training was really poo-pooed by art historians,” Seliger says. “Her article had always been sitting there, and nobody had really worked on this any further because it was one person’s opinion.”

But there was a snag. Unlike York, Canterbury was not going to dismantle its glass during the restoration of the stonework. “It didn’t need that,” Seliger says.

“When we were approached by Laura and Ian about access to the window for testing, I said, ‘You’re very welcome to look at it and (do) whatever you can do with it without taking samples. You’re not going to get permission to interfere with the substance. Over to you,’” Seliger says with a laugh. The decision was not hers alone anyway; numerous councils would have had to sign off, she says.

Adlington uses an X-ray spectrometer on stained glass at York Minster cathedral.

Despite her resistance to lab sampling in this case, Seliger has joined with other voices calling for more collaboration among art historians, the materials scientists eager to physically dig into treasures and the conservators and curators who protect the integrity of objects.

“When I started here in 1991, I was told, ‘You are a conservator. You are not to have any opinions on the materials you are working on. That is for historians, art historians and scientists,’” Seliger says. “But I’m the one who looks through the microscope for weeks and years on end … building up an awful lot of empirical knowledge. How is it that they don’t want the information that I can help with? And I was really disturbed by that. And I was not the only one.”

Over the past 25 years, various groups have begun to recognize that by working together, “we can actually come up with results that are greater than the sum of the individuals.”

Seliger says Adlington and Freestone responded with enthusiasm to the “you can look, but you cannot touch” gauntlet she threw down. “That meant that Laura had to become an inventor,” she says.

Adlington worked well with the team, Seliger says. “I felt completely safe in asking her to explain (her processes).”

Depressing Discovery

The four Canterbury windows in question had been split up during a restoration in the 18th century, with Roboam and Abia installed in the Great West Window and Nathan and King David in the Great South Window that needed current repair. Adlington tested and compared Nathan, installed between 1213 and 1220, with a control group — the panel of Methuselah, documented as made within six years after the 1174 fire, and the Great South panel of Ezekias, known to be made in the 1200s. Although Nathan and Ezekias were installed about the same time, Adlington found that Nathan contains glass matching the older type of glass in Methusaleh, making a pre-fire date for Nathan possible.

Before beginning work at Canterbury, Adlington returned to York to re-analyze the panels she had tested there when they were disassembled. Those panels were now back in their lead cames, like Canterbury’s windows, and she had to be sure the spectrometer produced accurate results on framed pieces, too.

Stained glass from the late 12th century in one of the Bible windows at Canterbury Cathedral shows the three Magi kings asleep and dreaming with an angel over them. <br />

“When I saw the results, it was really bad,” she says. “I was, like, ‘Oh, this is a failure. My research has been great up until this point, and now I just feel like I’ve hit a complete roadblock, and it’s over.’”

At issue was the distance between the spectrometer and the glass. With thick lead cames, sometimes the glass inside was slanted and thus slightly farther from the spectrometer, enough to skew the results.

Adlington’s easy personality has a steel core — her persistence. She loves solving a puzzle, and she says she can’t stop until she finds the missing piece. After her disappointment passed, “I don’t know, I’m just kind of stubborn. I just wanted to find a way around that.”

For worshippers in the Middle Ages, “walking into a medieval cathedral (was) … the closest experience you can get to heaven on earth.”

She needed something to keep the measuring distance consistent.

Her first attempt was pretty rudimentary, she says — a bit of sawed-off PVC pipe attached to the spectrometer with duct tape. “The machine heats up, and the duct tape actually can melt a little,” she says, able to laugh now.

Her other doctoral adviser suggested using the Department of Engineering’s 3D printing workshop. She taught herself the software, and she wouldn’t stop until she had created her device. She named it the Windowlyzer.

She has shared her Windowlyzer design with colleagues around the world. Because the attachment is lightweight, researchers can easily add and remove it. “And it’s cheap, which is good for archaeologists,” she says.

Adlington’s verification of spectrometer readings of framed glass meant she could investigate the Canterbury Cathedral windows and rely on the results without taking physical samples from the stained glass treasures.

Canterbury Cathedral’s Great West Window

Happy Historian

Caviness has not met Adlington, but the confirmation of the theory delighted the art historian.

“It’s always wonderful when people reconfirm each other’s results. And ideally we would always work with scientists as well. That would be wonderful. Laura broke through what was a very difficult problem,” Caviness says.

Seliger at Canterbury grew more and more excited as preliminary results firmed up into conclusions that led to international coverage about Adlington’s work, from British newspapers to the Smithsonian magazine. Stained glass windows that pre-date 1150 or 1160 “are as rare as hen’s teeth,” she says.

Germany’s Augsburg Cathedral, consecrated in 1065 in Bavaria, had been considered to have the oldest stained glass window in Europe, but its Prophets panels were recently dated to the early 1130s or later, putting Canterbury in contention as one of the oldest in the world.

“The trouble is, of course, they don’t come with a date … like 1136 or 1152,” Seliger says. “It’s not carbon dating (which works only for organic material.) It’s all the weight of the evidence. It’s circumstantial. … We are piecing together a mosaic.”

New Ideas on a Regular Basis

Freestone says Adlington was a great student. “She’s not scared to try anything. … She came to see me with new ideas on a regular basis, new plots, new graphs, new ideas about doing something. And she wasn’t frightened to be shot down by me, which she sometimes was.”

Seliger says Adlington was a pleasure to work with.

“She was extremely respectful of what we were able to bring to the table, and … she’s a fantastic communicator,” Seliger says. “She will never, ever take any questions you have lightly. She engages with my colleagues, with myself in such a way that we were all really excited about this.”

Adlington says finding that last piece of a puzzle, whether to bring a historical story into focus or to cinch a solution, gives her satisfaction. Seeing conservators’ passion for their work and their connection to history makes her happy. “They were recognizing humans in the past. I like that sort of kinship. … It’s really tangible how close they feel to these artists just by working on the same glass.”

Adlington says she revels in small moments, such as finding a tiny signature left by craftsmen working on York’s Great East Window in the 19th century.

Adlington demonstrates at Canterbury Cathedral how she uses the X-ray spectrometer, for which she invented the Windowlyzer attachment to allow precise measurements of the glass. She doesn’t normally work in the dark but took advantage of the lighting contrast to highlight the stained glass.

Getting at Knotty Questions

The future holds more discoveries, Seliger says. UCL and the University of York acquired limited funding to continue examining the windows in Canterbury. Personnel on site can do the spectrometer tests, and Adlington has analyzed their results remotely as a consultant.

Adlington would love to stay in stained glass research, but she wants to remain close to her Pennsylvania home and family, and the United States has less stained glass than do European cathedrals, so she is considering positions in related fields while she works as a freelance technical consultant and editor.

Freestone says the real significance of Adlington’s work is showing that the spectrometer technique works.

Just recently, Freestone says, researchers have “got up the scaffolding and been able to analyze windows which beforehand were completely inaccessible to scientific studies. She laid the groundwork for this.”

The new technology, the non-invasive technique and new collaborations will create research in other cathedrals, churches and museums, Seliger says. “This is a really thrilling time for us.”

The work reaches into the past and holds promise ahead.

Adlington says the project “gives us this vivid glimpse into the past,” and her innovations offer a way to shine a light on “this beautiful and unique art form and craft,” where more secrets await discovery.