Curt Baum couldn’t bring himself to talk about the letters he saved in a brown paper bag.

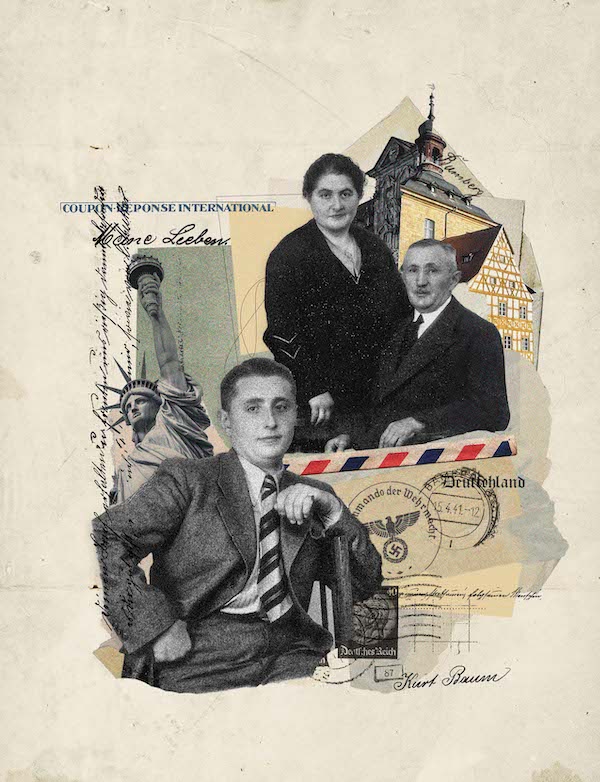

The letters had come to him beginning in 1937 and ending in 1941. He kept them inside a wooden trunk, which had accompanied him in 1937 as a 17-year-old traveling alone, barely speaking English, from his hometown of Bamberg, Germany, to the United States.

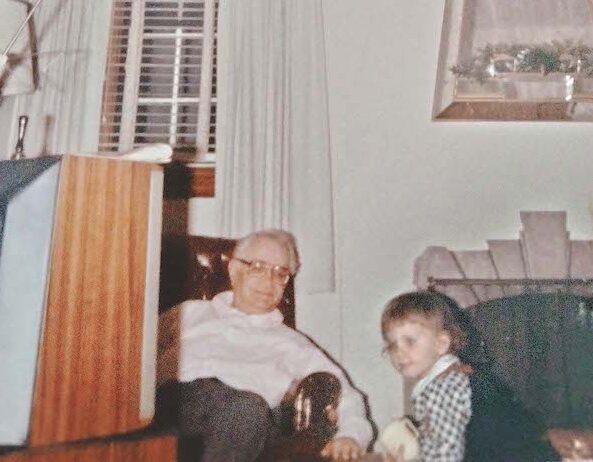

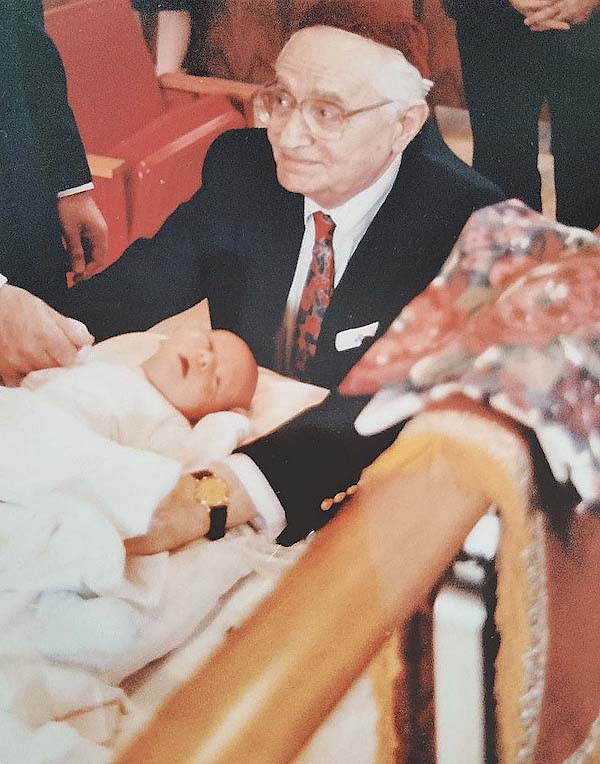

Curt Baum, born Kurt David Baum, would earn U.S. citizenship and a Bronze Star as a U.S. Army medic in World War II and in occupied Germany at the end of the war. He would do the hard work of a butcher in a Cincinnati meat-packing plant for 42 years. He would raise two successful daughters, play family pranks with his grandson and enchant his granddaughter with games and candy. And he would die in Cincinnati in 2004 at age 83 with dementia, after calling out every day for Rose, his wife of 55 years, who had passed away three months before him. “They were a package deal,” says his granddaughter, Lauren Postolski Cane of Charlotte.

Curt Baum was Jewish. His parents, Josef and Marie Baum, had booked passage to America for their only child to keep him safe. They saw the emerging Nazi threat in 1937 without knowing how far it would go — first to remove Jews from society, then to push them out of Germany, ultimately to the unthinkable, trying to kill all Jews and erase their history.

Curt Baum was collateral damage of the Holocaust. He escaped physically, with his story buried inside him under the debris of his grief and trauma.

But his history will not be erased. His story will be known.

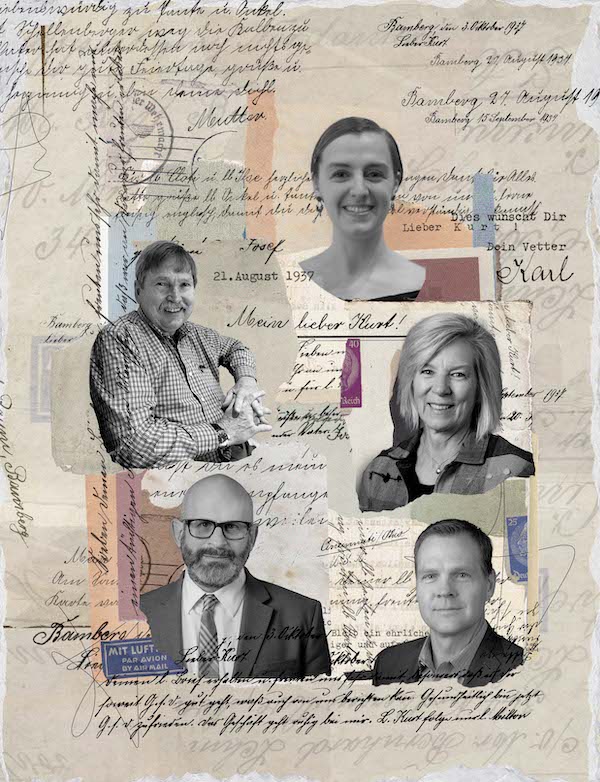

The letters, donated to Wake Forest in 2021 by Curt’s family, form the foundation of an innovative academic project and a pending book, thanks to an undergraduate’s senior honors project and the relentless work of four Wake Forest professors.

The monogrammed trunk where Curt stored letters. On top are the bag for Curt’s tallit, or prayer shawl, which was buried with him, and the bag for his tefillin, ritual leather straps wrapped around the arm during prayer. His grandson, Josh Postolski of Cincinnati, cares for the trunk and other mementos.

The project began in the University’s German department. Professor Rebecca Thomas (P ’04, ’12) and Associate Professor Grant McAllister (P ’26) supervised Fiona Burdette (’21), a German and mathematics major, as she transcribed and translated more than 100 pages of the letters mailed to Curt Baum, most handwritten by his parents. Josef and Marie Baum wrote in a historical script, a form of cursive writing, that is unreadable by most Germans today, but McAllister specializes in the script and taught it to Burdette.

When they were young, Curt’s daughters, Maralynn and Rita, explored Curt’s treasure trunk of mementos and found the letters, tucked under linens with the Baum monogram stitched by his mother. The daughters didn’t ask about the indecipherable German until they were older. “Every time we brought that up, he would be very upset and wouldn’t discuss them,” says Rita Baum Postolski, who lives in Winston-Salem. “He would cry.”

- From left, Rose Baum, daughters Rita and Maralynn, Curt Baum

- Curt, right, as a boy, with family

To help research the Baum family history and put the letters in historical context, the German professors invited two colleagues from the history department, Professor Charles “Chuck” Thomas (P ’04, ’12), who is married to Rebecca Thomas, and Professor Barry Trachtenberg, the Michael H. and Deborah Rubin Presidential Chair of Jewish History. The four professors plan to publish the book in the next year. It will include the letters, re-transcribed and re-translated by McAllister and Rebecca Thomas at a professional level, with essays by the four professors.

The Kurt D. Baum Family Collection, with letters, documents and photos, now resides in Special Collections & Archives at Z. Smith Reynolds Library. The professors hope the digital collection offers a resource to family historians, students and faculty, especially in researching the immigrant experiences of the Jewish diaspora. That aspect of the Holocaust has received less attention in popular culture and research than the death and direct destruction of that time, the professors say. The Baum story shows the complexity of the damage done by the Nazis to family relationships in indirect ways.

Curt’s mother, Marie Krauss Baum, center behind the chair, with family

Rebecca Thomas and her colleagues envision the work as the cornerstone of a larger digital humanities project that can produce collaborations at Wake Forest and with other universities.

The letters “can be used in history studies, Holocaust studies, translation studies and literature … by lots of people who have various ways of looking at this material and give them something very specific that’s a narrative they can build on,” Rebecca Thomas says.

She says the letters portray Nazi policies affecting individuals day to day, “like a seismograph where you could look at the historical record and then map that onto the experiences of this family.”

The letters, she says, offer “a set of flesh-and-blood characters in Germany, … and the symbiosis of what’s going on on (the German) side of the Atlantic and the United States. … So, we really have both sides of the Atlantic all in one story.”

Clockwise from top: Fiona Burdette (’21); German professors Rebecca Thomas (P ’04, ’12) and Grant McAllister (P ’26); history professors Barry Trachtenberg and Charles “Chuck” Thomas (P ’04, ’12)

The letters portray Nazi policies affecting individuals day to day, like a seismograph where you could look at the historical record and then map that onto the experiences of this family.

A son suppresses his pain

What started as an academic training ground in transcription and translation for Burdette evolved into a heartbreaking journey into the trauma of Curt Baum and his parents.

The biggest gap in telling Curt’s story is that his voice is missing. The family has no letters written by him, only letters to him from his parents and other relatives in Germany and the United States. He spoke little of his experiences to his daughters. If he discussed them with his wife, she didn’t share it with their daughters.

What was it that was so painful to Curt Baum in these letters?

At first, nothing.

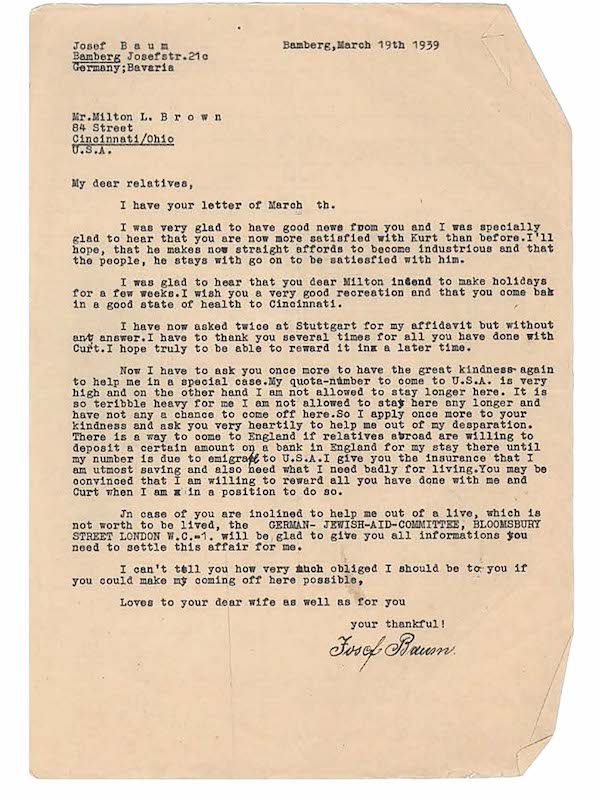

His parents express love and concern, along with normal, if persistent, parental nagging. But over time, the letters show Josef Baum’s fear and panic engulfing him, and he writes searing words to his son. Josef sees his teenage boy as his only lifeline to survival, and Curt is not responding as Josef thinks he can and should. The letters stop in 1941.

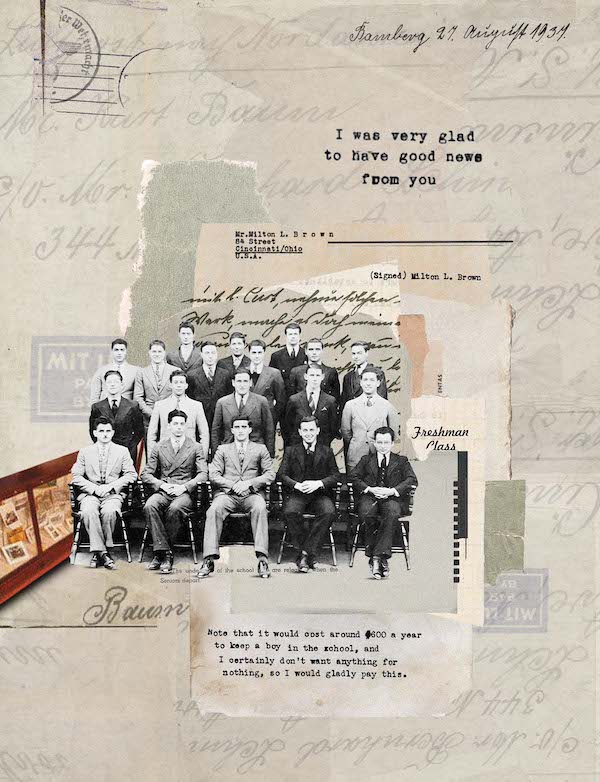

Curt arrived in the United States in September 1937 because his mother, Marie, had reached out to a wealthy cousin, Milton Brown, to sponsor Curt’s move. Brown, known to the family as Uncle Milton, owned Jenny High-Fashioned Apparel for Women and Misses in Cincinnati, as well as a farm.

"Uncle Milton" Brown, Curt Baum's U.S. sponsor

U.S. immigration law required a major commitment from a sponsor. Uncle Milton had to provide housing and show sufficient funds to support Curt until he earned citizenship, found work or left the country. This was to ensure that immigrants did not burden American welfare systems. The United States was in the Great Depression of the 1930s, and conflicts around the world were sending large numbers of refugees from many continents.

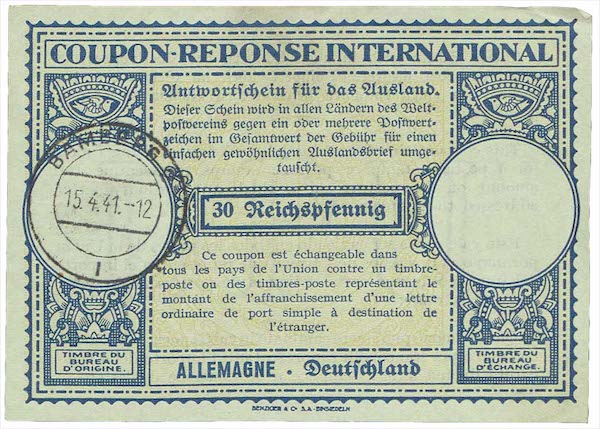

Uncle Milton, the U.S.-born son of German immigrants, and his wife, Flossie, from Montgomery, Alabama, had no children. He promptly found a place for Curt to live in another state, at the National Farm School in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. The school was founded by a rabbi in 1896 to teach science-based agriculture on a 1,200-acre working farm. Uncle Milton appealed to a longtime friend who was board chair at the school, suggesting that it seemed a logical place for Curt, a cattle trader’s son who could later work at Uncle Milton’s farm or elsewhere. He paid $600 for Curt to go there for a year.

Uncle Milton writes to the board chair: I hope they can take this boy on at once, as it is practically impossible to have him live with me in Cincinnati and get any sort of an English education at all, as we are living away out in the country where there are absolutely no facilities for him to obtain same.

Professors Barry Trachtenburg and Chuck Thomas uncovered a trove of correspondence about Curt — but nothing by him — in the archives of the farm school, which evolved into Delaware Valley University today.

Brown’s home in Cincinnati<br />

Students at the National Farm School in Pennsylvania, where Brown sent Curt in 1937. Curt is not listed in any yearbook photos.

Solicitous parents write regularly

Josef and Marie mailed their first letter to their son in August 1937 before Curt had disembarked from the SS Manhattan in New York and traveled on to Cincinnati. Marie writes to him in the language of a mother who already misses her only child and sends kisses and greetings: My dear Kurt, I hope you are healthy and in good spirits. Surely you survived the beautiful crossing without getting seasick. … I’m sure it was a warm and touching welcome. Please write and tell us all about it. Mother

Josef urges his son to be a respectable, capable person so they hear only good reports about him: I also send you kisses and greetings … from, your Father, who thinks of you always.

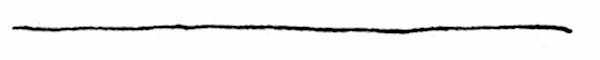

They had included in his luggage a typewriter and international coupons with which to buy postage stamps, as well as his most valuable items, a Leica camera and his suit coats.

In October 1937, Marie addresses her son for the first time as Curt, rather than Kurt, indicating he anglicized his name, though his parents spell his name both ways in ensuing letters.

On Oct. 4, 1937, he entered a daunting environment at the farm school, about 30 miles from Philadelphia. He had learned some English in Bamberg but not enough to join classes mid-semester. The school had no room he could share with any of the eight to 10 German refugees among the 185 students, so he shared quarters with an English-speaking student in a dorm with a few Germans.

One of the many coupons Curt’s parents gave him for international postage stamps

Curt faced six months of milking cows and feeding chickens and hogs before he could begin classes in April 1938. The dean later writes that Curt has picked up English amazingly well. Uncle Milton quickly criticizes the school for not giving Curt the promised formal instruction in English. In letters over the next months, Uncle Milton alternates between harsh criticism of the school and harsh criticism of Curt, often at the same time.

Uncle Milton’s letters do not depict an easygoing or patient guardian, despite his largesse.

Tension builds in the first year

Throughout 1937, Curt’s parents and other relatives share a steady stream of news about family and friends leaving Germany. They are fleeing the thunderclouds of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP). This Nazi government sees Jews — as well as many others, including Slavs, Jehovah’s Witnesses and gay or disabled people — as inferior and malignant.

Over and over, Josef and Marie stress to their son the importance of proper behavior and good morals. From his mother: I implore you to be careful in everything you do, especially when it comes to cars, horses and the farmer’s pretty daughter! Don’t get too friendly with the ladies. It leads to no good.

Photos from National Farm School yearbooks<br />

His parents begin a perpetual refrain of questions and requests: Write more, write every week, you’re not writing enough; quit smoking; send photos; describe your room, what you do every day. Who is doing your laundry and darning your socks? Send birthday cards to your grandmother, your aunt. Did you hang the picture of us we sent?! We need to hear from you.

In another often repeated point, Josef urges Curt to write regularly with gratitude to Uncle Milton and other U.S. relatives “because Americans want to be acknowledged when they do something for you.”

Curt never fulfills these expectations. Maralynn Baum Martin says her father told her and her sister, Rita Baum Postolski, that he regretted not writing often enough to his father, but Curt didn’t elaborate.

“It becomes clear very early on that Curt is being told that the honor of the family rests upon his behavior, which seems to me such a tremendous burden to be placed on a boy in this situation,” Professor Trachtenberg says.

Circumstances would grow much worse in the coming years, both for Curt and his parents.

The Baum Letters Timeline

Skip timeline and continue reading

January 1933 Adolf Hitler appointed chancellor of Germany.

February 1933 Curt Baum, born Kurt Baum to Josef and Marie Baum, celebrates his Bar Mitzvah in Bamberg, Germany.

September 1937 Curt, who is Josef and Marie’s only child, arrives to a safer life in Cincinnati, sponsored by a wealthy cousin, Milton L. Brown, called Uncle Milton. Curt’s parents write regularly to their son.

October 1937 Kurt anglicizes his name to Curt. Uncle Milton sends him to the National Farm School in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

January 1938 The Nazi government cancels Josef Baum’s cattle-trading business license.

March 1938 Curt’s mother dies March 18.

April-June 1938 Curt spirals into a breakdown when news of his mother’s death reaches him. He also has surgery for appendicitis, receives harsh letters from his father and reads judgmental words from Uncle Milton, who threatens to send him back to Germany.

August 1938 Josef tells Curt he has shamed the family and must realize he could end up in a labor camp or worse if he is sent back to Germany. Josef, hoping to gain sponsorship, too, tells Curt he must make Uncle Milton happy.

February 1939 Josef writes that he will likely perish and blames Curt. Uncle Milton removes Curt from the farm school and finds him a job as a butcher’s helper in Cincinnati.

April 15, 1941 Josef finally receives Uncle Milton’s sponsorship and awaits a seat on a ship. It is his last letter to his son.

Curt Baum (born Kurt), left, with his parents, Josef and Marie Baum, in Bamberg, Germany <br />

Wake Forest tackles a translation puzzle

Rita and Maralynn entrusted Rita’s daughter, Lauren, with Curt’s letters, and Lauren was determined to get them translated. “I was so close with my mother’s parents that I really felt like we needed to know what was in those letters,” Lauren says.

The family members are all close. Rita, who retired as a social worker and director of a Jewish-supported assisted living center in Cincinnati, moved with her husband, Sam Postolski, a pharmacist, to Winston-Salem in 2013 to be near Lauren, a speech therapist. Lauren and her husband, Dr. Zachary Cane, a podiatrist, now live in Charlotte, and Lauren is a full-time mother to Curt, 9, and Rose, 3, named for Lauren’s grandparents. Lauren’s brother, Josh Postolski, is a pharmacist in Cincinnati.

Curt Baum’s older daughter, Maralynn, was a special needs teacher and administrator of group homes in several states before retiring in Cincinnati, where her husband, Ed Freeman, is administrator for a pediatricians’ group. Maralynn has three stepchildren and six step-grandchildren. Lauren, 38, and Josh, 31, consider her a second mother.

It was Maralynn who suggested approaching Wake Forest’s German department, Lauren says. Professors Grant McAllister and Rebecca Thomas say they routinely get requests for translations but can’t take on those time-consuming projects in addition to teaching and research.

McAllister transcribed and translated a couple of letters for Lauren because she was persistent, and he is the only faculty member who knows the historical script, thanks to his work with the archives of the German-speaking Moravians who founded Winston-Salem. Germany replaced the script with a modern one in 1941.

I was so close with my mother’s parents that I really felt like we needed to know what was in those letters.

Overloaded as department chair at the time, McAllister couldn’t translate more letters. Into the picture came Fiona Burdette, a student with a love of languages and deciphering scripts and codes.

McAllister often entices students into learning the script. Burdette took the bait enthusiastically as a sophomore. She translated Moravian material at a pace that amazed McAllister. “Fiona is just possibly the smartest human being I’ve ever met in my life,” McAllister says.

Burdette, who grew up in Winston-Salem, was a Presidential Scholar in Cello Performance. She played cello and mandolin with the regional Martha Bassett Band and the Dan River Girls, an award-winning folk music band with her two younger sisters. In her first year at Wake Forest, she won a W. D. Sanders Scholarship for promising students in German and spent four weeks in Berlin in a summer immersion program. After graduating in 2021, she won a Fulbright Scholarship to study Egyptology at Humboldt University of Berlin and expects to complete her master’s degree early next year.

Fiona Burdette (’21), right, playing mandolin at the UNC School of the Arts with her younger sisters, Ellie, left, and Jessie, in their folk band, the Dan River Girls

Her father, Dr. Jonathan Burdette (P ’21), is a neuroradiologist at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist. Her mother, Shona Simpson (P ’21), is an author with a Ph.D. who taught English for several years as an adjunct at Wake Forest. Fiona studied German at Wake Forest for five semesters when she was 12 and 13 and read German literature with her high school French teacher, who spoke German.

She has considered various professional pursuits, from music to medical school, but puzzles remain irresistible. Burdette compares decoding scripts and hieroglyphics to writing proofs in mathematics, her other major. “You have to try out a lot of different things in your head in order to find the correct path through to the end,” she says.

Rebecca Thomas and McAllister worked with Burdette in what Thomas sees as quintessential Wake Forest.

The initial goal was to give Burdette practice with the script in her junior year by transcribing and translating five letters for Lauren to give to her mother as a birthday gift. The professors would “double-team Fiona, and she would have the full attention a couple of hours a week from two full-time Wake Forest faculty members,” Rebecca Thomas says. “That’s not an experience that undergraduate students get at many universities, right?”

The professors then proposed to help Burdette translate all the letters as her senior honors project.

You have to try out a lot of different things in your head in order to find the correct path through to the end.

Burdette did a fantastic job, the professors say, but producing a book required their professional re-transcription and translation to meet peer review standards. The professors often spent two or three hours at a time together puzzling over one paragraph or just one word. “We had to go through it with a fine-tooth comb,” McAllister says.

Letters, archives show painful days for the Baums

Josef and Curt both confronted a year of crucibles in 1938.

In mid-January, Josef loses his license to trade cattle, as the government pushes out Jews to take their assets. Marie writes: So our business is done for. You have no idea how much we still need Uncle Milton’s help. Josef begins to see that he must go to America, and he will need Uncle Milton as a sponsor, so he wants Curt to make his guardian happy.

On Feb. 7, 1938, Marie and Josef criticize Curt’s “thoughtlessness” and “indifference” for forgetting Josef’s Feb. 2 birthday in his latest letter. Josef cautions Curt not to repeat his mistakes, referring to unnamed transgressions: I beg you again: don’t do as you did in Germany! Don’t be foolish. … If dear Uncle stops supporting you, then you’ll be on your own.

Curt learns in a letter dated Feb. 27, 1938 — two days before he turns 18 — that his mother is bedridden in great pain. Josef’s letters refer to phlebitis, an infection of the veins, and Marie’s descendants, Maralynn and Rita, say family members told them that a cow kicked Marie, and she didn’t receive treatment for her infected leg because she was Jewish.

On March 18, 1938, the worst happens. Marie dies at age 45.

Josef and Curt are bereft, but as the months pass, instead of comforting each other across the miles, Josef criticizes more, and Curt appears to communicate less.

This must have been one of the worst, if not the worst, periods of (Curt’s) life.

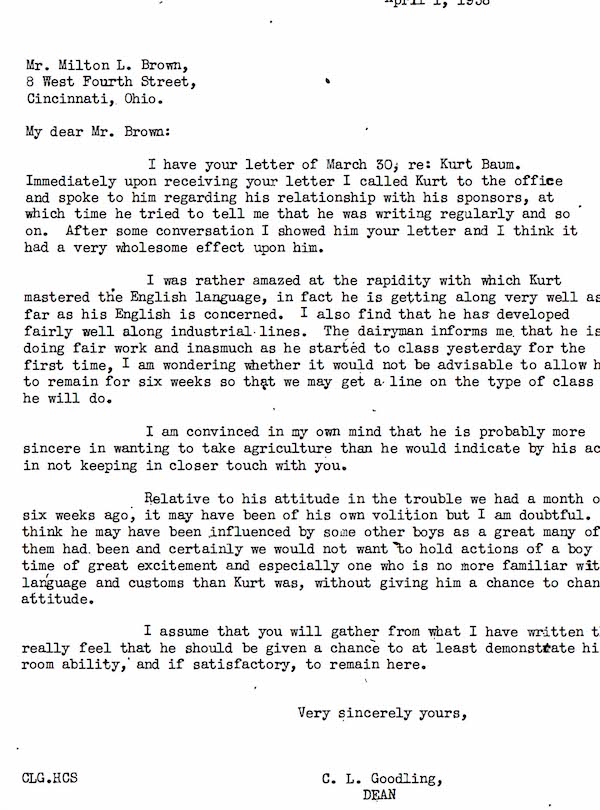

Curt meets April 1, 1938, with the farm school dean, who reports to Uncle Milton that Curt has rapidly learned English, is doing well at farm work and deserves a chance to succeed in the classes he has finally started. But when letters arrive soon after that with the news that his mother is gone, Curt’s grief overtakes him.

“This must have been one of the worst, if not the worst, periods of (Curt’s) life,” Professor Chuck Thomas says. “He leaves Nazi Germany, arrives at the home of a distant relative in Ohio who is speaking a different language, is almost immediately sent to the farm school to do day labor, loses his mother, suffers an attack of appendicitis and eventually leaves the school, all within a span of about 15 months. While there, he is also surrounded by about 180 boys and young men who are sufficiently dissatisfied with the conditions at the school that they go on strike, after which one of the strike leaders (a student) writes to Milton Brown that Curt is on the verge of a nervous breakdown.”

The student says Curt is “completely unbalanced” and has attempted suicide after the dean threatened to expel him and Uncle Milton accused him of hastening his mother’s death by failing to write to her often enough.

The dean and Uncle Milton deny the student’s account, with Milton writing that either the student is lying or Curt is. Uncle Milton withdraws Curt for 18 days in April, then sends him back, only to have Curt land in a hospital with appendicitis until June 5. He has missed many weeks of classes, is too weak for farm work and keeps skipping classes and tutoring.

Uncle Milton makes an existential threat

Uncle Milton learns of Curt’s poor attendance and makes an extreme threat — to ship him back to Germany.

Brown writes: I am tired of being bothered with your nonsense and your stubbornness. Either you see that I do not get any further complaints or I will take immediate action to have you sent back to Germany. … Now this is your last chance, and I am not bluffing or fooling.

Going home would doom Curt. The Nazis had not yet begun full-scale genocide but excluded Jews from virtually all public life and were imprisoning Austrian Jews in concentration camps after seizing the country.

When Josef hears about Uncle Milton’s threat, he turns his wrath on his son, rather than Uncle Milton, from whom he needs sponsorship, or the restrictive U.S. immigration system that accepts only a fraction of desperate Jews, or the Nazis, who censor all letters and need little excuse to terrorize Jewish citizens.

The dean of the farm school writes to “Uncle Milton” Brown that he is optimistic Curt can succeed, but Curt will spiral into grief when he learns days later of his mother’s death. National Farm School letters and documents courtesy of Delaware Valley University

If Curt returns to Germany, Josef writes on Aug. 22, 1938: You’ll be arrested as soon as you get off the ship and sent to a labor camp. … Not only did I lose dear Mother first, but she is turning over in her grave. The shame. … You are a worthless son. If someone has all the good luck you have had and has squandered their chances, that person should be hanged. — your despairing, Father.

Curt never recovers at the farm school. Records show a long list of violations and punishments. Uncle Milton withdraws him for good on Valentine’s Day 1939.

Meanwhile, the relationship between father and son is deteriorating as fear besieges Josef. The infamous “Kristallnacht” rampage against German Jews in November 1938 burns through Bamberg, though Josef’s house is spared. A month later, Josef writes that he has registered with government officials for permission to leave Germany, as still allowed. But the list has 24,400 names: It’s going to take a long time until my number is called.

Josef’s panic builds

Josef writes on Feb. 8, 1939, a week before Curt departs the farm school in failure: Dear Milton would have taken care of me and sponsored me, but now he’s leaving me in the lurch, too. I now also have to stay in Germany and perish, all because of you, because you are a disobedient, dishonest person.

The wreckage of those words to a son is hard to fathom.

Uncle Milton relents and submits a sponsorship application, but it is delayed by omitted details. On Nov. 4, 1940, Josef begs Curt to sponsor Josef’s immigration himself: I ask that you respond to me immediately when you receive my letter, otherwise I will never write to you again.

One of Josef Baum’s few letters translated into English for him as he implored “Uncle Milton” Brown to help him flee to the United States<br />

Josef believes Curt would need $3,000 in the bank — 2½ years of the median income in 1939. Curt doesn’t respond.

But five months later, Josef writes again. He has Uncle Milton’s sponsorship, and Milton has paid $490 for Josef to sail from Lisbon, Portugal,

if he can catch a rare departure.

While still chastising his son — I don’t deserve this from you — Josef signs off as he has since 1937: from your ever-loving, Father.

The letter of April 15, 1941, is the last one from Josef Baum. He is 61 years old.

A family grapples with Curt’s story

The letters from Josef Baum and other relatives paint Curt as an irresponsible, heartless son, and they are painful to read, say Curt’s daughters and grandchildren. They don’t match the Curt Baum they loved.

Lauren Cane says, “It’s like I was reading about somebody else. That wasn’t my grandpa.”

But she says her grandfather was too important to her not to uncover his story.

Her grandparents took care of her in early childhood. Curt had retired from E.Kahn’s and Sons meats, a company famous for its hot dogs.

Curt and Rose Baum on their wedding day in 1948

Curt with his elder daughter, Maralynn Baum Martin, at her wedding

Although Maralynn and Rita say Curt was a strict father, he loosened up, as many parents do, with grandchildren. Lauren says Curt and Rose Baum were “the definition of grandma and grandpa,” and Lauren’s brother, Josh, agrees.

Lauren savors memories of helping Curt trim the bushes and playing horsey with him by tying chairs together with string for a buggy. He kept Bulls-Eyes caramels and hard candy in his pocket and would lean over conspiratorially to say, “Want some candy?”

She recalls the scent of his aftershave and the feel of stubble on his handsome face. He always wore his red Kahn’s jacket and his Cincinnati Reds baseball cap, and he listened to games on the silver radio in his pocket. He took her to the social gatherings he organized for Kahn’s retirees.

Curt with his granddaughter, Lauren <br />

Lauren, a night owl, often called her grandparents after midnight when her anxiety flared up, and they would calm her. They ended every call by telling each other, “I love you, heart and soul.”

Josh Postolski says he remembers throwing a rubber ball around the living room with Curt at family gatherings, until the ball knocked over a lamp or, the final straw, hit Rose.

Josh also has sadder memories of his grandfather’s decline with dementia. Josh stood by Curt’s deathbed at what was then Cedar Village, a Jewish assisted living center, where his mother worked until 2013. He held Curt’s hand and soothed him with wet washcloths on his forehead in his final hours.

Curt with his grandson, Josh

Lauren, a night owl, often called her grandparents after midnight when her anxiety flared up, and they would calm her. They ended every call by telling each other, "I love you, heart and soul.”

Isolation growing up in Bamberg

The professors’ research helped put the harsh words of Josef and Uncle Milton into historical context, showing the pressure Curt faced as a distressed young man, even before leaving Germany. Bamberg deteriorated for Jews during Curt’s adolescence.

By the time Curt was born on Leap Day 1920 in Bamberg, Jews had inhabited Germany for at least 1,600 years, with ebbs and flows of acceptance and persecution. Many Jews, including Josef Baum, served their country in World War I, a loyalty worth little to the Nazis, even those who had fought beside them in that war.

The synagogue in Bamberg in flames during pogroms against Jews across Germany on Nov. 9-10, 1938, known in German as Kristallnacht, or Night of Broken Glass. Photo courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute for the Study of German-Jewish History and Culture<br />

Just in that moment when he is kind of growing into an awareness of the larger world, he learns that his entire society is poised against him.

Curt celebrated his Bar Mitzvah upon his 13th birthday in February 1933 — a month after President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as chancellor of Germany.

“Just in that moment when he is kind of growing into an awareness of the larger world, he learns that his entire society is poised against him,” Professor Trachtenberg says.

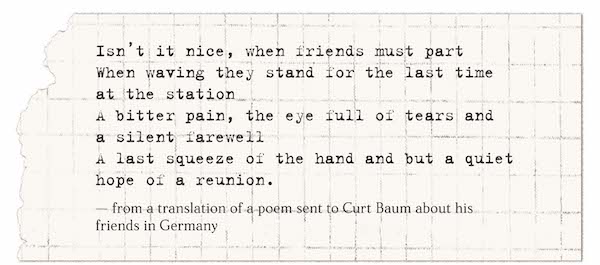

But Curt had friends who loved him. A poem by an anonymous family member or friend about Curt’s departure from Bamberg captures his melancholia and the mischievous side his grandchildren would see in him.

The poem teases that he often “fled your mother’s scolding” and annoyed her “as a defiant lazy boy.” It honors him as “the one who thought up so many good tricks to play.”

It chides him: How often did you sit on the bench in the little garden, sulking, no answers to our questions/But now your moods are all forgotten/We only want to carry your friendship in our hearts. … Even when you are far away, you will always be near to us.

Nazi policies imposed damage capable of producing Curt’s “moods” in adolescence.

— from a translation of a poem sent to Curt Baum about his friends in Germany

In April 1933, the government declared a Jewish boycott, and stormtroopers with bayonets stopped people from entering Jewish stores. When Curt was 16, Bamberg banned Jewish students from sports, social groups and educational programs. Then the city banned Jewish students entirely from public schools and isolated them in a makeshift school in the synagogue. Hitler Youth ambushed Jews on the streets.

Different anxieties pressed Curt in the United States, where Americans expected immigrants like Curt to pull themselves up by the bootstraps, regardless of whether they were seeking opportunity or fleeing as refugees from war, Professor Trachtenberg says.

Curt’s daughter, Maralynn, says her father never lost his sense of guilt about his rift with Josef. And Curt never gave up trying to find out what happened to his father, as Curt built a life that would have made Josef proud.

Modern Bamberg. Photo by Sebastian Puskeiler/Unsplash

As a medic with the U.S. Army’s 126th Evacuation Hospital in Belgium in late 1944 and early 1945, Curt would have cared for injured troops from the bloody Battle of the Bulge, says Professor Chuck Thomas, who specializes in German military history. In the spring of 1945, Curt’s unit deployed into Germany and treated German prisoners of war, newly released Allied POWs and people rescued from concentration camps.

“He would have been among the first to offer aid and medical assistance to survivors of Nazi Germany’s brutal 12-year reign,” Chuck Thomas says.

In July, Professor Barry Trachtenberg took this photo of a sign that says “livestock business” at Josef Baum’s former home in Bamberg, Germany, where Curt grew up. The current residents told Trachtenberg they found it on the property, where Josef Baum lived and operated a cattle-trading business. Professors are still researching a claim Curt filed for German compensation for the Nazi seizure of the property. <br />

Curt searches for his father’s fate

Curt’s daughters say he told them he drove an Army Jeep to his home in Bamberg in search of his father. The Germans who answered the door wouldn’t talk to him, but he still gave them a box of chocolates. (Andreas Goeller, who joined the Nazi party in 1937 and served in both World Wars, had claimed Josef’s home, Trachtenberg found in Bavarian records.)

Curt knocked next door. As a boy, he had played with the family’s son, who also became a soldier. The family would say only that someone took Josef away.

The former Baum home in Bamberg today

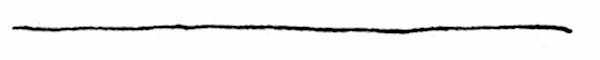

When Curt and Rose Baum were 70, Maralynn helped them try to determine Josef Baum’s fate through a Holocaust documentation service. Professor Trachtenberg found the request forms Curt submitted in 1990 in both German and English, the only documents found so far in Curt’s handwriting besides his signature. Curt writes in block letters: I want to know what happened to my father + where he is buried.

Curt’s request in English at age 70 to a Holocaust documentation service for information on his father’s fate. Also submitted in German, the requests are his only handwriting found so far, other than signatures.<br />

The initial response to Curt in 1994 reported Josef’s final destination as Buchenwald or Mauthausen concentration camps, but that referred to a different Josef Baum. A followup response in 1996 said Curt’s father was deported to the east and died at an unknown time and place.

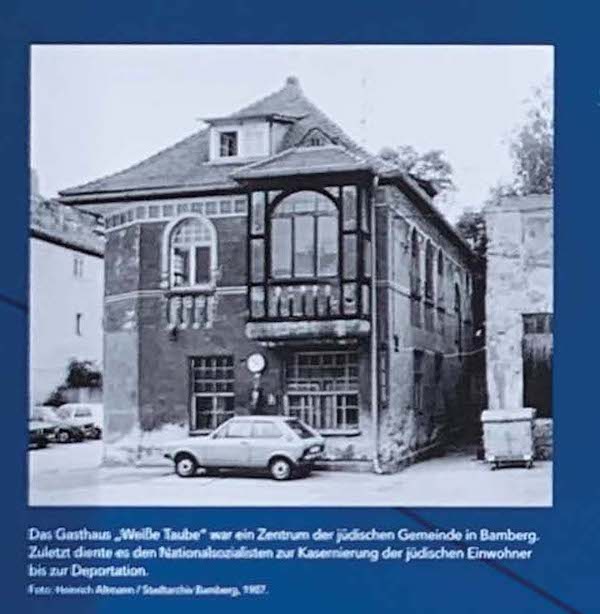

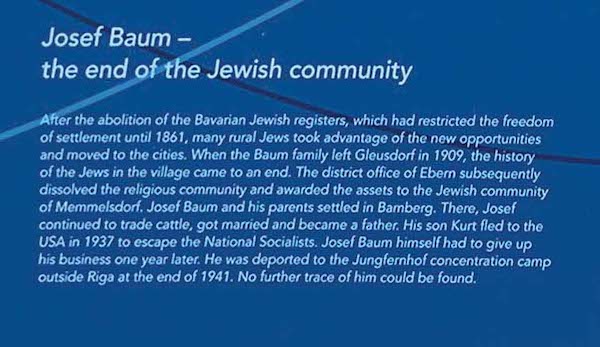

Trachtenberg discovered more detail in multiple records. In late November 1941, the Nazis ordered Josef, with two days’ notice, to show up at the former White Dove tavern in Bamberg with clothing, supplies and money. He boarded a train that delivered more than 1,000 Jews, including 118 from Bamberg, to Jungfernhof concentration camp outside Riga, Latvia. Only three Bamberg passengers were among the few who survived the brutal camp. Josef perished there.

He might have died from disease, starvation or the severe cold, Trachtenberg says. Or soldiers might have murdered him in the forest, where they shot thousands after ordering them to lie in a trench that became a mass grave. The scenario is unknown.

Marie Baum’s gravestone, discovered and photographed in Bamberg by Professor Trachtenberg

The White Dove tavern in Bamberg, a Jewish gathering place later used for organizing deportations of Jews to concentration camps

A museum plaque with Josef Baum’s history as the last Jew to leave his village birthplace of Gleusdorf, Germany, in 1909 after cities opened trades to Jews. The surprise discovery while visiting Gleusdorf deeply moved Professors Grant McAllister and Chuck and Rebecca Thomas, bringing Rebecca to tears. Jews turned over the synagogue there to non-Jews who promised not to desecrate it with animals. They honored their promise. It is a museum now.

Honoring memories in present day

Trachtenberg provided a bit of peace to the family when he and a longtime colleague, a German-Jewish historian, searched last year for hours in Bamberg and found Marie Baum’s gravestone.

“We just cried,” Trachtenberg says. “It meant so much to find it.”

He placed stones on the grave, a Jewish tradition, and recited the Kaddish, or Jewish mourner’s prayer.

“As important as the letters are, there’s something kind of ephemeral about them,” Trachtenberg says. “To find a permanent site for Marie just seemed a very important connection for this family, whose history has been marked by movement and migration and deportation and destruction, just to see that she had a resting place in a cemetery that was not destroyed like so many in the Holocaust.”

These Stolpersteine, or Stumbling Stones, are 4-inch concrete cubes with brass plaques inscribed to commemorate those killed or persecuted under Nazi political doctrine. The stones are usually embedded in pavement, to be discovered, or “stumbled upon” in everyday life. The three Baum memorials will go in front of the former Baum house in Bamberg in a ceremony next year, to be attended by Curt Baum’s grandson, Josh Postolski, and possibly other family members. The Stolpersteine project, initiated by German artist Gunter Demnig in 1992, had created 100,000 memorials as of May, most for Jewish victims. Photo: Fiona Burdette (’21)

Rita says she understands her father’s reluctance to talk about his pain. Her mother-in-law survived Auschwitz concentration camp but could never discuss it, and neither could the several dozen Holocaust survivors Rita cared for in the retirement home she led. But Rita says her father would approve of telling his story.

Lauren Cane agrees. She is sad that her grandparents had passed away before young Curt and Rose were born, though Curt, a precocious boy who reads at college level, knows about his great-grandparents. As a toddler, little Curt told Lauren one night of a vision: he was seeing the couple outside his bedroom window. They told him they were proud of Lauren and that she had beautiful children. Lauren hopes to take Curt and Rose to Bamberg someday.

Clockwise from left: Rita Baum Postolski, Lauren Postolski Cane, Rose Cane and Curt Cane in front of ZSR Library, which houses their family photos and documents. Photo: Lyndsie Schlink

Maralynn says the letters have made the family proud of the man their father became.

“Because of all that happened to my father, one might expect that he would have spent much of his life being angry, but he never was,” she says. “He taught my sister and I about Tikkun Olam, which in Hebrew means to heal or repair the world.”

Her family has done that, she says — Rita with elderly people, Maralynn with teens and adults with special needs, Lauren as a speech therapist and Josh as a pharmacist.

Maralynn Baum Martin with her nephew, Josh Postolski, in Cincinnati. Photo: Margaret Li

“Until the day he died, my father questioned why he survived while his parents perished. No one can answer that question, but I do think he led a successful, meaningful life and most assuredly did his part to heal the world. Furthermore, he left a legacy of future generations to carry on that tradition.”

The Nazis did not succeed. Curt Baum is not invisible.