James Brim ('87), director of the Food Bank of Northeast Georgia in Clayton. Top: A driveup food distribution

FOLKS looked out for each other in Slab Fork, West Virginia, the coal camp town where singer Bill Withers was born. The town inspired him to write “Lean on Me,” his No. 1 hit in 1972:

“Lean on me

When you’re not strong

And I’ll be your friend.

I’ll help you carry on.”

The song tells it true, as James Brim (’87) sees it.

Brim was 8 years old and growing up in Slab Fork when that song topped the charts. He remembers Withers — his mother’s cousin — jamming at their house when his band rolled into town in a tour bus.

Brim says his father, a coal miner, worked 12-hour shifts deep inside the earth. He cleaned off the day’s black coal dust and came home to his wife and six children in their shotgun home with two bedrooms and one bathroom.

Yet Brim’s dad found time to tend a huge garden whose bounty the family shared with anyone who came calling. “My dad said, ‘Well, everybody needs food. Everybody is not as fortunate as we are.’ That’s how I got started.”

Slab Fork, West Virginia in 2011. Photo: Creative Commons. Below, the coal town in 1947. Photo: National Park Service

Brim’s father retired after 33 years as a miner and moved his family back to his hometown of Mount Airy, North Carolina. That was where Brim discovered his talent for sports. He excelled at football in Mount Airy and at Wake Forest and made his way to the NFL.

But James Brim always nurtured a soft spot for hungry people. Today, using his expertise from more than two decades in a food manufacturing career, he pours just as much energy into helping needy families in the Appalachian mountains as he did catching passes for the Demon Deacons and the Minnesota Vikings.

manufacturing career, he pours just as much energy into helping needy families in the Appalachian mountains as he did catching passes for the Demon Deacons and the Minnesota Vikings.

“I love this job,” says Brim, 59, a man always in high-energy mode as director of the Food Bank of Northeast Georgia’s six-county mountain operation in Clayton, near the North Carolina border. “I never get tired of it.”

He has carried with him the compassion his parents instilled in him in the coal camp, where “everybody in the community was together and cared about each other. … Nobody went without anything,” Brim says. From Wake Forest, Brim carried forward not only Pro Humanitate values, but the importance of teamwork — and an eye for entrepreneurship so many Deacons parlay into success.

Brim gets to know people — and their pets — as he loads groceries into their vehicles at the food bank’s monthly distribution.

“He’s just a force of nature,” says Dr. Tom West (MD ’81), an Atlanta anesthesiologist who retired to Clayton and is president of the Wake Forest Medical Alumni Association. West and his wife, Dr. Laura Pinner West (MD ’81), also a physician, drew Wake Forest Magazine’s attention to the work Brim is doing.

“He just makes you feel good about community service,” Tom West says.

Food and other goods line the shelves inside the food bank’s “store,” where nonprofit partners select items to distribute to their clients.

A food bank with an entrepreneurial twist

Brim manages the 63,000-square-foot food bank in Clayton in a former grocery store that anchored the Covered Bridge Shopping Center. That is where he, a staff of five and a cadre of volunteers hold a monthly food giveaway of more than 30,000 pounds, one of the food bank’s many events and programs. They share bags of groceries to get people through the week or the month.

Nearby Rabun Gap Presbyterian Church gives away 40,000 pounds from the food bank in another monthly offering. Brim says those two events can sustain many families.

The church’s minister, Rev. Don Barber, is a board member of the original Food Bank of Northeast Georgia in Athens, which hired Brim in 2016 to run the mountain location. “What James has done here is unlike anything we know about in other food banks in the country,” Barber says.

What makes the food bank unusual is that Brim also manages the entire shopping center, which a donor bought and gave to the food bank. The leases from the businesses there feed the nonprofit’s coffers.

Brim and a food bank team designed and equipped food production lines and a commercial kitchen inside the former grocery building. Small businesses rent time on the lines or in the kitchen to make products they couldn’t afford to produce two hours away in Atlanta — high-end chocolate; sustainable protein bars; turkey, chicken and beef jerky; veggie burgers; frozen French fries that start as unwashed, uncut potatoes and emerge in bags ready for freezing. Brim rented the kitchen in 2021 to the catering team feeding the film crew making the movie “Dog Gone” with Rob Lowe.

A beautiful teaching kitchen, worthy of Bon Appétit and run by 13 volunteers, offers cooking and nutrition classes. Young children and parents learn to cook together. Teens learn to navigate cutting boards, stoves and ovens. Those with diabetes or other health challenges learn to manage their diets. Community folks show up to learn from top area chefs.

“I was helping other people because … that’s what life’s all about is helping people.”

The building holds a store stocked with food and supplies, including meats and other frozen goods in a giant freezer, most donated by grocery stores. Partner nonprofits or agencies pay pennies on the dollar to shop from the shelves for their clients.

Brim can list dozens of ideas he’s implemented, such as sending opened dry goods, which he can’t give to people, to hog farms in the area for feed. In exchange, the farms donate hogs for pig-pickin’ fundraisers.

When the pandemic squelched live events in the teaching kitchen, four women volunteers known as “The Kitchenettes” developed recipes for “The Little Cookbook.” Brim talked his fellow members of the Rotary Club of Clayton into financing it. The 2022 book, selling for $40, has brought in $8,000.

Dave Sweeney of Tiger, Georgia, cooks his gluten-free David’s Seed Bars in the commercial production kitchen in the food bank and sells them each week at farmers’ markets in Atlanta. “I couldn’t do it without this place,” he says.

No idea is too small. He asked for a donation of a dollar apiece from local folks to stand on the food bank’s rooftop vantage point and watch holiday fireworks fill the sky.

Businesses in the shopping center get a good rate and contribute back to the food bank. A heating and cooling business helps with repairs and maintenance. The Clayton Tribune runs food bank news.

Each time Brim tells a story of an “I’ll-scratch-your-back-You-scratch-the-Food-Bank’s” arrangement, he leans forward, makes eye contact and shows his winning smile, capping the story with “So that worked out pretty good.” Sometimes he adds with an extra twinkle, “That worked out REALLY good.”

Turning obstacles into opportunities

When Brim showed up for seventh grade in Mount Airy, he knew his parents were stretched financially. He didn’t want to burden them, but he wanted things his parents couldn’t afford. So, he took a job in the school cafeteria standing by a huge trash can, cleaning trays and clearing tables every day.

Young Brim asked the cafeteria workers why some children kept their heads down and wouldn’t look at him as their class filed in at lunchtime. The women told him those students had to stay in the cafeteria even though they didn’t have food money. They were embarrassed.

Brim was making $240 a month. “I said, ‘Well, give them some of my money,’” Brim says. “Then the cafeteria ladies started giving money; then the teachers started giving money.”

Brim kept giving. “When I left high school, there was no kid with their head down. Everybody as a community was helping each other out,” he says.

He's just a force of nature.

The obstacle? Hungry kids. The possibility? Share in the fruits of his work to fill children’s stomachs.

“I was helping other people because … that’s what life’s all about is helping people,” Brim says.

Learning to run and tackle

Brim didn’t get a total Mayberry welcome at school in Mount Airy, the feel-good model for “The Andy Griffith Show.” Some of his classmates called him “Trash Boy” and summoned him over in the cafeteria to take their trays. He didn’t take it seriously; they were just kidding, he says.

As he discovered his talent for sports — basketball, baseball, track and football — he learned to take a hit and give one on the football field, starting in seventh grade. As he grew into his 6-foot-3-inch frame, he admits, he got a bit of satisfaction in hard-tackling some of his Mount Airy High School teammates during practice and giving them a ribbing: “Who’s Trash Boy now?”

The obstacle? A little disrespect. The possibility? Go the positive route and turn it into admiration as a running back who made Parade’s 1982 All-American High School Football Team. He developed a football brotherhood. Brim was named to the Surry County (North Carolina) Sports Hall of Fame in 2011.

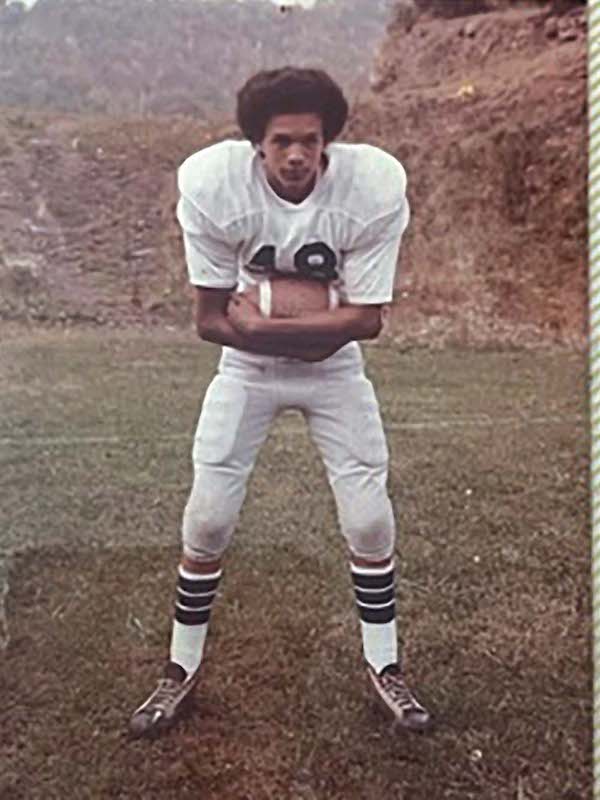

James Brim in his football uniform for a sixth-grade recreational league in West Virginia.

Football gave him even more. His high school team and their opponents in the Shrine Bowl of the Carolinas visited the Shriners Children’s Greenville hospital in South Carolina to meet the children there, some severely ill or missing limbs.

The boys grumbled on the bus ride to the hospital, but no one, including Brim, had dry eyes on the ride back, he says. He was so moved he later took his own sons, Marcus and Justin, there. “Those kids kind of showed my kids the way.”

Deacon days

Brim played sports, in part to keep himself out of trouble but also because he dreamed that “one of these sports is going to take me somewhere.”

Football offered a path to a Division 1 university. He had attended Governor’s School at Wake Forest in high school, and his parents could drive 30 minutes to campus to watch their youngest son score touchdowns, so Brim became one of the first Black students from his area to enroll as a Deacon.

“I had an offer from UCLA and other places,” he says, “but I wanted to be close to home.”

His family had functioned as a team, with his three brothers and two sisters always taking care of each other. “I wanted my family to see what I can do.”

He proved his value to the Deacons as a wide receiver. He stands ninth in program career receptions and 12th in career receiving yards. He was named to the 1985 All-ACC offensive team.

James Brim with the Wake Forest Dance Team during Homecoming 2021. <br />

He appreciated meeting students from all over the world at Wake Forest and majored in history to understand how people of all nationalities operate as communities. From his teammates, he learned to stick together through wins and losses. “Al Groh was a coach who cared about the players, and that meant a lot to me.”

Brim moved into the NFL in the summer of 1987, with a few credit hours left to complete his degree. He played briefly for the Vikings in Minnesota. Crossing the picket line during a players’ strike wasn’t an easy decision, but he had a family of his own by then. (He is divorced, and his two grown sons live in Winston-Salem and High Point, North Carolina. They often use his Deacon season football tickets.)

After the Vikings let him go, “I could have crawled in a hole and said, ‘Hey, I’m giving up.’ But … I wanted to go out and make a difference in the world.”

A natural progression

Brim worked at Cross Creek Apparel, then moved into a food manufacturing career at General Mills, then at Malt-O-Meal cereals in Minneapolis. He moved to Anderson, South Carolina, as superintendent of a bread plant for the Kroger grocery chain.

Brim never forgot that no one should go hungry and no food should go to waste. In his career, he found ways to supply nonprofits with perfectly good food that was headed for the trash, for reasons that didn’t affect food quality, such as managing shelf space.

All of those experiences made him the choice when a headhunter recruited him to lead the Clayton food bank. The Food Bank of Northeast Georgia in Athens wanted to expand beyond its eight counties with a new mountain operation, which serves six Appalachian counties and often helps nearby residents of Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Florida.

“We don’t say no to anyone,” Brim says.

Clayton, Georgia. Photo: Scott Poss/Skypop Aerial Photography

Tourism’s contradictions

In Clayton, elegant homes dot the steep mountainsides just minutes above the charming downtown district. Tourists fill the town and Rabun County in season for hiking, kayaking and rafting in the scenic gorges. They imbibe at local breweries or stroll through festivals.

Tourists may miss the harsher side of the area. Hunger and poverty have historically plagued the struggling agricultural economy that began with Scottish and Irish immigrants and now encompasses many Hispanic immigrants. (Locals aren’t fond of mentioning it, but the 1972 film “Deliverance,” a harsh depiction of Appalachia, was filmed in Rabun County.) In Rabun County schools, more than half the students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches.

Barber, the minister whose church gives away food each month, says Clayton and Rabun County are in the throes of a rural-to-resort shift.

Housing and rental prices have soared with the influx of affluent retirees, luxury vacation or Airbnb homeowners and families who fled Atlanta or other cities during the pandemic and continue to arrive. Multimillion-dollar homes sit on the banks of two large lakes in the area, including a home owned by famed Alabama football coach Nick Saban.

Within the rural-to-resort transformation, Brim is finding opportunities, all for Pro Humanitate purposes. The affluence, besides infusing property tax revenue, supports food bank fundraisers such as silent auctions and celebrity chef cook-offs. A sold-out, $300-a-plate dinner with each course by a different chef raised $12,000, Brim says.

Many new residents generously contribute to the food bank. During the pandemic, the wealthy owners of lakeside homes raised $360,000 in a giving challenge. Many serve on local nonprofit boards. Among them are the Wests, who knew Brim from his community work, including at Barber’s Presbyterian church, where they are members.

Dr. Tom West (MD ‘81) and his wife, Dr. Laura Pinner West (MD ‘81), at their mountain home in Lakemont, Georgia, near Clayton. They support the food bank that James Brim leads.

“James has made himself one of the most highly respected people in our community,” Tom West says. “He has won the trust of this community, and people have no idea how much he has done.”

The food bank charges Barber’s church only $1,500 for the 40,000 pounds of food the church gives away each month. Barber says the food bank estimates the value of that food at more than $1 million a year. New church members add contributions each year to offer more food.

The church sits next door to an expensive private academy, Rabun Gap-Nacoochee School, on a 1,400-acre hilltop campus. Barber says students who volunteer for the food event gain new perspective as they see lines of cars backed up from 5:30 a.m., waiting for groceries on the third Saturday of every month. The food distribution even rattled perceptions of some of Rabun Gap’s Black students from low-income urban communities, he says. “They couldn’t believe it when they saw hungry white people who needed groceries from the food bank to survive,” he says. “It was life-altering for them to understand the prevalence of hunger affects all people.”

He has won the trust of this community, and people have no idea how much he has done.

A man about town

Barber notes that Brim shows up every month with his truck driver to help with the church giveaway. “There wouldn’t be many directors of a food bank that would be on the truck at 5 a.m. bringing the food to my church.”

Brim and his small staff of five acknowledge every gift. “I don’t care if you give me a dollar or you give me $1 million, I’m going to write a thank-you card to that person who just gives me that $1, because maybe that’s all they had, you know?” Brim says.

Everywhere Brim goes, people know him — at the Italian restaurant nearby, at the dedication of a new business downtown where he cuts the ribbon, at a conference center holding a reception for a new book on women in Appalachian history by the Foxfire Museum in Rabun County. (“You should have had this event at the food bank. Would have saved you a bundle,” James says only half-jokingly to the museum director.)

Brim doesn’t miss an opportunity to benefit the food bank and the community.

He collects large donations from Walmart, which gives away more than any other local retailer in food and household necessities, diapers and other returned items. He persuaded Amazon to certify the food bank as a recipient of its returned merchandise slated to be discarded. Brim auctions or sells it all — televisions, appliances, housewares — to raise funds. Some items, especially shoes or clothing, are needed giveaways.

Brim moves pallets of food to replenish the lineup of bags his staff and volunteers fill for distribution.

He’s always checking for shoes on clearance, because school guidance counselors say it’s one of their biggest needs. As he gives us a tour of downtown, a friend joins us in an outdoor store. His friend says, “I know where I’ll find him. He’s in the shoe section.” He was.

He takes us on a driving tour in his Toyota 4Runner, with a Wake Forest license plate frame. Along a winding mountain road, rusting and decrepit houses could be mistaken as abandoned if not for the cars or toys in the yards. For some, Brim says, “Meth and alcohol are big problems, and there’s nowhere else they can afford.”

Never judge

Brim leads his work from the lines, not from an office or from a distance.

At 7 a.m. on the second Saturday in March, it’s sunny and clear in Clayton, but the Weather Channel says it’s 37 degrees and feels like 33. Brim is already at the food bank. He’s moving fast, as he always seems to do. He has kept in shape since his days as an athlete, he says, with gym workouts, running, hiking and kayaking.

We don't say no to anyone.

On this morning, the first half-dozen vehicles already form a line in the parking lot an hour before the 8 a.m. event. This is the monthly “mobile pantry,” so called because Brim and the volunteers drop supplies into truck beds or back seats as each driver stops at the food bank, an efficient method begun during the pandemic.

Driving a forklift, Brim delivers a pallet with 18 boxes of frozen pork patty packages. Volunteers add them to pre-packed paper and plastic bags. Each brown bag holds eight oranges, two sweet potatoes, a dozen eggs, almonds, canned goods, raisins, macaroni, frozen pie crusts and a flier listing other resources. The items change each month.

Volunteers line up the bags on sidewalk tables. At another table, a representative of Rabun County Head Start hands out applications for the preschool program. The director of a food bank partner agency called Rabun County Family Connection shares information about its crisis services.

Everyone knows what to do, except perhaps the teen whose mother dropped him off for community service, ordered after he got caught vaping at school. (Brim says he tells schools and courts to “send them my way, and I’ll put them to work,” and some court defendants can donate $320 to the food bank in lieu of service.)

Volunteers at the monthly food distribution <br />

Trucks, many shiny and expensive-looking, wait in line. Brim tells his volunteers they can’t assume they know anyone’s circumstances. Some are taking food to others in need. “My staff looks at it like this — how do you know that they just didn’t borrow that car? How do you know that they just didn’t lose their job? We don’t judge anybody. We don’t turn anybody away. There’s hungry people all over.”

The same is true every day. Volunteers deliver packages to people who can’t leave home, and Brim gives emergency bags to anyone who comes to the food bank for help.

Stephen and Cherye Weintraub help at every monthly giveaway, just one of their volunteer efforts. He retired as a computer programmer; she still works as a design consultant.

“It’s all about camaraderie and helping the people who need it,” Cherye Weintraub says. She’s had moments of hunger as everyone does, she says, but hasn’t experienced food insecurity. “I’ve been hungry but never been hungry.”

She tells of a man who came by in a car with his dog. “He said, ‘I don’t want to take food from someone else because I’m homeless and can’t cook. Do you have anything I can eat? Or something for my dog?’ James gave him food and dog food. I always wonder what happened with them.”

The line of cars seeking groceries handed out in front of the food bank office

Charming the clients

Brim takes the lead for the first rush of 15 cars in line, with more arriving. He knows many of the people and keeps them smiling as the volunteers play classic pop songs on a speaker.

One car has a handicapped tag on the rearview mirror. On the roof of another car, a rope holds down two sets of box springs and a mattress. Brim speaks to everyone.

“He’s going to want three (bags),” Brim says of an approaching truck. He tells the driver, “You’ve got one ham and two bags of frozen meats. Maybe you can invite them over to your house and cook the ham for everybody. … You have a good one, sir.”

To a driver with a gray-haired passenger, Brim says: “Look at that young lady over there with you.”

To a man driving alone, “Where’s your wife at?”

“At the house,” he replies.

“Be sure and tell her I said hello.”

Of his volunteers scurrying, refilling and handing out bags, Brim says: “Aren’t they great?”

With a half hour to go, Brim is back on the forklift, and volunteers are breaking down boxes to recycle them. The volunteers gush about Brim and praise the way he aims to delight children. “James is a super guy to work with,” says volunteer Renée Ramsay. She shows photos of him wearing an elf hat next to Santa Claus at Christmas, when volunteers give away age-specific toys for children, with batteries and other goods for their families.

By the time Brim and the volunteers have returned everything to its place inside, the sun has risen high and dispatched the cold. Brim and his crew have handed out more than 200 bags of food. They have done what they can on this Saturday morning to let their neighbors lean on them.

As Brim would say in the language of his own refrain, this day has worked out pretty good.

Help for a Heartbroken Mother

Thanks to the Sharing and Caring Thrift Store and Food Pantry, Tonya and Wade Scroggs and their son, Caleb, could give his disabled sister — their “angel” — love and care at home with a steady stream of live butterflies to delight her.

Caleb Scroggs with his sister, Celladonna, who died at age 5.

The women who run the store don’t know whether they could have continued helping families like the Scroggs without the Food Bank of Northeast Georgia’s mountain branch in Clayton and its director, James Brim (’87).

Brim’s organization owns the shopping center that houses the food bank in a former grocery store, and Brim handles leasing and managing the other spaces, including a Family Dollar, a pizzeria and a nail salon, to produce revenue for the food bank.

The store, operated by local nonprofit Rabun County Sharing and Caring, sells thrift items and offers free clothing and food from the food bank in the store’s pantry. Founded by a group of church women in 1984, the nonprofit helps families in need. It had operated in a large, free space in a county building until the county needed the space in 2021. The founders were desperate for a place to move.

Brim came to the rescue, says Gail Whitmire, the nonprofit’s vice president.

“I knew James,” says Whitmire. “He said, ‘I got a place. It’s smaller.’ As for rent, he said, ‘Don’t worry about it. We’ll figure it out.’ … We are so happy. James saved us.”

The location has improved sales and donations enough that the nonprofit’s two annual scholarships grew to $1,500 from $1,000 each, she says.

A short time on Earth

For Tonya Scroggs, life without the women who run the store is unimaginable. She says they kept her, Wade, Caleb and Celladonna fed and clothed for years, allowing them to make the most of Cella’s short but precious life.

Cella died in October 2020 at age 5. She had undergone surgery immediately after birth and lived with Aicardi syndrome, a rare neurological disorder. She suffered five to 25 seizures a day, had only a tiny field of vision and could not talk or move herself. Collapsed lungs required breathing and suction treatments every three hours.

Tonya Scroggs with Gail Whitmire, left, and Linda Giles, right, whose help allowed Scroggs to stay home with her terminally ill daughter.

Scroggs lost her job in Atlanta 12 years ago. She came to Clayton to live with her mother and walked 15 miles into town for supplies because they had no car. She married Wade Scroggs and gave birth to Caleb, now 10. Life was good.

It fell apart when Caleb’s baby sister was born. Cella needed 24-hour attention, in case her seizures or respiratory failure required an ambulance or air lift, which was often. Neither Tonya nor Wade could work.

“I couldn’t afford clothes for us or the children. We relied on the food (from the store),” says Scroggs. She learned emergency procedures that kept Cella alive so she could perform them at home, reducing Cella’s exhausting hospital trips.

“Every breath that child tried to take, I would’ve given her mine. I would have given her my eyes, heart, my lungs,” Scroggs says as she shares her story in the store’s office.

Cella ultimately succumbed to an incurable infection and took her last peaceful breath at home. Despite the grief, Scroggs wouldn’t trade one minute. “She was here for a reason.”

Scroggs says Cella taught her to be patient, to never give up and to stay calm despite sleep deprivation. “It’s the memories, … not your money. It’s not your things. It’s how important each moment is,” she says.

Scroggs now works as head cashier at the Clayton Home Depot and gives thanks every day for the job. But her husband has health issues, and she spent five weeks at home in the spring recovering from acute pancreatitis. They depend on the food bank and the store.

Linda Giles, the president of Sharing and Caring, says, “We owe this all to James. Without him, we wouldn’t be here.”