Even in this age of social media, friendships can be fragile. Vows to keep in touch — with roommates, fraternity brothers or sorority sisters, co-workers and drinking buddies — often are casualties of time and distance.

Often, but not always.

This is a story about one six-decade friendship, forged on Pub Row at what was then Wake Forest College, that recently culminated in a singular event: publication of a compelling memoir by a Wake Forest Distinguished Alumni Award recipient in 1983 and member of the University’s Writers Hall of Fame.

Jo DeYoung Thomas (’65), has written a memoir, “Striving: Adventures of a Female Journalist in a Man's World.”

The writer is Jo DeYoung Thomas (’65), and her memoir is “Striving: Adventures of a Female Journalist in a Man’s World.” A life story that reads like a novel, “Striving” is an inspiring tale of courage and persistence, not only in pursuing the news — wherever and whatever it takes — but also in breaching the barriers meant to deny women their rightful place in society.

Jo and I were reporters for the campus newspaper, Old Gold & Black, in the early 1960s. We learned on the job, working on the OG&B under the tutelage of the esteemed E.E. Folk Jr. (1921, P ’47).

Jo was the best writer on an unusually talented staff of journalists that included Al Hunt (’65, D.Litt. ’91, P ’11), who went on to be Washington bureau chief of The Wall Street Journal and executive editor of Bloomberg News, and Donia Whiteley Steele (’65), who became a respected film critic for The Washington Star (now defunct). Their talent was recognized in 1964 when OG&B won a Pacemaker Award, considered the equivalent of a Pulitzer Prize for college student publications, from the Associated Collegiate Press as one of the nation’s five best college newspapers.

The editorial staff of the 1963-1964 Old Gold & Black. Seated: Charles Osolin ('65) and Lineta Craven Pritchard ('65, P '93); standing: Charlie Winberry ('64, JD '67), Jo DeYoung Thomas ('65), Al Hunt ('65, D.Litt. '91, P '11), Donia Whiteley Steele ('65) and Rachel Floyd Harjes ('66, P '04). Photo from The Howler

The early ’60s were a turbulent time at Wake Forest. The Civil Rights Movement was gaining steam and the first Black students were arriving on campus. Wake Forest’s students and administration were under constant fire by the North Carolina Baptist Convention, with which the college was still affiliated.

OG&B covered the turmoil relentlessly and came in for its share of flak. The heavy guns, though, were leveled at The Student literary magazine after it published a parody of the Rev. Billy Graham’s visit to the campus in 1962. The headline: “WF to Forsake Sin!”

The pressure forced President Harold Tribble (LL.D ’48, P ’55) to ban publication of the magazine, outraging the student journalists on Pub Row and much of the rest of the campus. No one was more outraged than Jo. She led an intense lobbying campaign that finally resulted in reinstatement in March of 1964. She left OG&B to become editor of the resurrected publication.

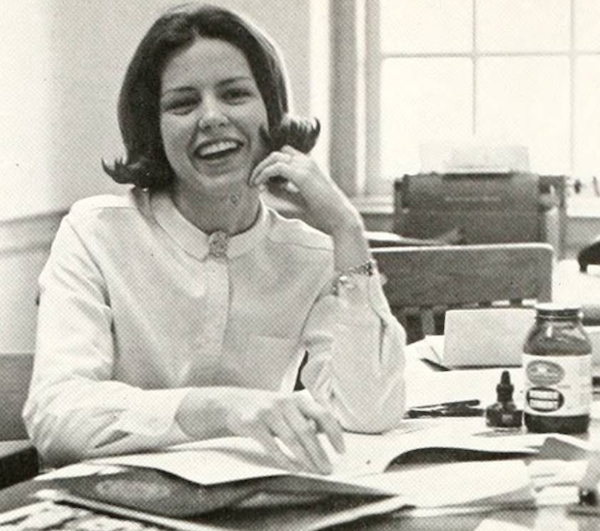

Thomas at the editor's desk of The Student. Photo from The Howler

We both graduated in 1965, Jo with numerous honors. I joined the Air Force, while Jo went to graduate school and later became one of the first female recipients of a prestigious Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University.

Resolved to pursue a journalism career in the face of stifling gender bias in the newsroom, Jo went on to blaze a trail for women reporters that many others soon followed. By chance — the city desk was short-handed — she became the first female reporter for The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star in 20 years. (When she asked why she was hired, the city editor affably told her, “Great legs. And you can write.”)

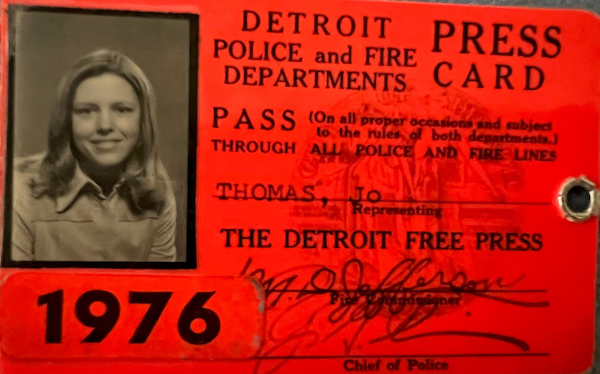

After completing her Nieman Fellowship, she moved to the Detroit Free Press, covering organized crime on the docks and in the trucking depots despite terrifying threats of violence. She was also co-winner of a 1974 Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for an 18-part series about psychosurgery.

Thomas rests on a curb to sooth her aching feet while covering a police siege during a strike at a Detroit auto plant. Photo courtesy of Thomas

She joined The New York Times in 1977 and set out on a distinguished 25-year career as an investigative reporter, foreign correspondent, bureau chief and assistant national editor. Her pioneering work was fraught with danger — she was once mistakenly targeted by assassins — along with triumphs, backstabbing and controversy. These and many other adventures are grippingly recounted in her memoir.

Meanwhile after four years in the Air Force, I pursued a parallel career but with none of the barriers or risks that Jo faced. I was Washington correspondent for newspapers in North Carolina and Florida before becoming national editor of the Atlanta Journal in 1978. Jo and I stayed in touch — writing letters, sharing thoughts about career choices, visiting each other’s homes.

Then life intervened. We both remarried. I left journalism for a rewarding career in government and private-sector communications. Jo turned, very successfully, to teaching. After an occasional phone call, we drifted apart.

“I feel extremely fortunate to have had a career doing something I love.”

Our friendship finally was resurrected thanks to the reach of social media. I found Jo on Facebook, and we reconnected. That’s when I learned that she was working on a memoir: She posted that a virus had infected her computer and destroyed much of her book. Fortunately, it was backed up and recoverable.

That wasn’t the last of Jo’s challenges — and here her book’s title becomes even more appropriate: “I had two years of rejections from agents, big and small,” she says. “The agents told me publishers only wanted memoirs from celebrities.”

Undaunted — of course — she undertook the arduous task of self-publishing. With the help of daughters Susan and Kathleen, she launched a website about the book and prepared an electronic version, which debuted Oct. 6 on Amazon. Hardback and paperback versions are also available. Her son-in-law Ismael Limardo, a sound engineer, helped her record an audio version. She even created her own aptly named imprint, “99 Cups of Coffee.”

“I feel extremely fortunate to have had a career doing something I love,” Jo says. “At a time when democracy is under attack, truth-telling newspapers are accused of publishing ‘fake news,’ and journalists are imprisoned or killed, journalism is more important than ever.”

Jo’s advice for young women aspiring to a journalism career, or a career in any field, for that matter: “Hang in there. Women can do anything men can do — only better!”

Charles Osolin (’65) is a science writer for the National Ignition Facility in Livermore, California. After eight years as a journalist, he worked for the White House Council on Environmental Quality, the U.S. Senate, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the National Safety Council and Argonne National Laboratory. He lives in Rio Vista, California, with his wife, Mary, and their son, Ryan.