Analyze a Film | Cook Like You’re in Venice | Make the Most of Your Happy Moments | Deliver On the Field and Off | Heal a Community Through Knitting | Make the Perfect Hot Dog | Stop the Spread of Conspiracy Theories | Get to Carnegie Hall | Be a Demon Deacon Mascot | Propagate Pro Humanitate | Talk to Your College-Age Daughter (for Dads) | Sail Around the World

__________________________

How to Analyze a Film

Don’t worry that examining a film will ruin it for you, says Professor of Communication Woodrow “Woody” Hood, director of film and media studies.

He often reassures his students that breaking down film into its components won’t disturb the magic. “Seeing how the magic works actually makes it even more magical. You kind of go, ‘Wow, that’s cool. That’s amazing that they did that,’” Hood says.

Hood, who is also director of critical and creative media, says analyzing a great film that you love can be difficult; you may not notice the technique if you’re caught up in a well-told story. He often has his students begin by critiquing a bad movie.

“They go, ‘Oh, my God, that acting is so bad.’ I’m, like, ‘Yes, it is. But why? What are they doing? Or what are they not doing?’” Hood says. Does the emotional tone or body language feel inappropriate, overdone or underplayed?

Photo: Samuel Regan Asante/unsplash

In cinematography, look for how the lens is directing light and how colors give a feel to the story. How are scenes framed? “A long shot can often mean that the character is isolated in some way. If it’s a closer shot, then we’re becoming more intimate, but they can play with those things,” he says. In editing, long takes might convey drama, while quick cuts convey action.

Hood, a director, sound designer and composer, says diegetic sound exists within the movie world, and characters can “hear” it, such as disco music in a dance-floor scene. Only the audience can hear non-diegetic sound, such as orchestral music during a deserted beach scene. How does this affect the viewers’ emotions or their perception of the story? Close your eyes to focus on the sound.

Hood sees sound as “a hidden weapon in filmmaking.” We often tune out ever-present background sounds in daily life since we can’t “close” our ears. “You can slip all sorts of things into an audio track, and the audience doesn’t notice it’s there, but it’s affecting you.”

Assessing a film can help push you past watching the same types of movies over and over, Hood says. “Sometimes, you need a tool to be able to crack open a film that may be not immediately to your liking. … I think it opens you up to all sorts of amazing new experiences.”

__________________________

How to Cook Like You’re in Venice

Bianca Artom is well-known among Wake Foresters for her role in helping to transform a neglected palazzo on Venice’s Grand Canal into the home of the University’s first residential program overseas. But she also inspired untold numbers of students to learn how to cook like a local. The herb garden she planted on Casa Artom’s rooftop terrace lives on today, along with recipes she scribbled on index cards for favorites, including insalata caprese — chunks of tomato, mozzarella, olive oil, wine vinegar and, of course, freshly picked basil.

Photo courtesy of Alessandra Beasley Von Burg (P ’14)

When she died in 1994, friends assembled her dishes into “Bianca’s Italian Table,” and a few copies of the spiral-bound book, along with her recipe files and newspaper clippings, reside in Z. Smith Reynolds Library’s Special Collections & Archives. She was never taught to cook while growing up in Venice, so she figured out by taste and feel how to recreate the flavors of her childhood after she and her husband, the late Dr. Camillo Artom, a prominent biochemist and medical doctor who was Jewish, fled fascist Italy in 1939 for Winston-Salem.

Here, she experimented with Southeastern U.S. substitutes for Venetian staples, such as “domestic” rice as a stand-in for the arborio traditionally used to make risotto. She relied heavily on fresh vegetables to carry off Venetian favorites from risi e bisi (rice and peas) to fagiolini soffogai (“suffocated” beans), with her version praised in the cookbook as “soft, but not mushy, and exquisitely flavored.”

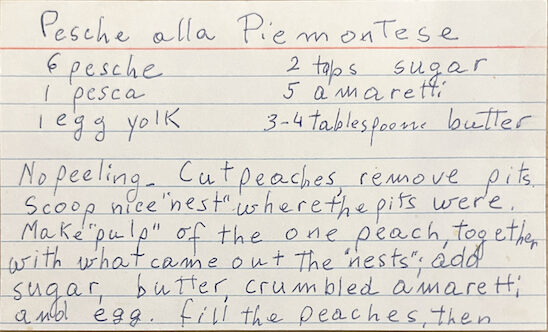

One dessert in Artom’s files, pesche alla Piemontese, or “peaches Piedmont,” dresses up a fruit that both regions love. The ingredients: seven peaches (“no peeling,” she notes), an egg yolk, two tablespoons of sugar, three tablespoons of butter and five amaretti (crumbled almond macaroons). After cutting the peaches in half and removing the pits, scoop out a “nest” and mash the pulp with the remaining peach. Mix the pulp with the other ingredients, fill the “nests” and bake in a buttered dish at 350 degrees for an hour. Delizioso!

__________________________

How to Make the Most of Your Happy Moments

Professor of Psychology Christian Waugh (P ’27) is wary of quick-fix suggestions on “how to be happy.”

“That is such a loaded thing for people,” he says. “It’s basically a lifelong massive journey of your entire soul and being and social life, so I would just be a little wary about oversimplifying that to just one little technique.”

That said, research does offer some suggestions: Express and clarify your emotions, and especially share good feelings verbally in the moment with the people who are with you.

Capturing colorful memories at the Holi Festival on Manchester Plaza in March 2023<br /> Photo/Tsing Liu (‘23)

“We asked the question, ‘What happens if you take the time to verbalize how you’re feeling about something?’ And what they’ve shown before with negative emotions is that sometimes verbalizing your negative emotion, saying literally the words, ‘I feel angry; I feel sad’ … helps clarify them and as a result can actually help decrease them because you have more of an idea of what’s going on and how to deal with it.”

Waugh wanted to know whether expressing positive emotions would decrease or increase them.

“In a couple studies we found that it increased them,” he says. Emotions tend to be amorphous and under the surface. “By saying, ‘In this moment, I feel good about this; this is amusing to me; this is exciting,’” the verbalization clarifies the emotion and brings it to the surface, he says. This allows people to savor the pleasure a little longer. Writing down your emotions can have the same effect.

Sharing positive moments with others by telling them in the moment what made you feel good can bring more clarity, deepen the emotion and make you remember it more vividly, Waugh says. It embeds those moments into the tapestry of your life.

“When we think … about ‘Who am I? Am I a happy person or am I a less happy person?’ essentially we’re kind of informally counting up the experiences in our lives that we count as happy or not, right? … Not only increasing those experiences, but making sure they get into your memory and your identity matters a lot for being a happy person.”

__________________________

How to Deliver On the Field and Off

Dr. Andrew “A.J.” Lewis (’94, MD ’98) has always breathed baseball, playing catcher in high school — and resuming that position as an OB-GYN, delivering babies for the past 25 years in Winston-Salem.

Lewis passed along his passion for baseball to his own two sons. And when they gravitated to pitching in middle school, “I realized that I needed to learn more about it so I could help them and keep them safe and healthy,” he says. Combining his love of science and sport, he crisscrossed the country to study pitching mechanics and coaching at Driveline Baseball in Seattle, spring training in Florida and the Texas Baseball Ranch.

“I learned a lot about how they should move the lower half of their body to accommodate this very violent motion with their arm in their upper half — how to take some of the stress off their arms and put it into their legs,” he says. Their high school’s pitching coach quit in the pandemic, and Lewis filled in. While the sons were being recruited to college teams (Appalachian State University and UNC-Chapel Hill), their dad was scouted, too.

“I learned a lot about how they should move the lower half of their body to accommodate this very violent motion with their arm in their upper half — how to take some of the stress off their arms and put it into their legs,” he says. Their high school’s pitching coach quit in the pandemic, and Lewis filled in. While the sons were being recruited to college teams (Appalachian State University and UNC-Chapel Hill), their dad was scouted, too.

The Carolina Disco Turkeys, a collegiate summer team formed in Winston-Salem in 2021, asked Lewis to be the team’s first pitching coach, despite his being on call occasionally at gametime.

And one balmy summer night, the doctor’s pitching and catching lives converged: Lewis checked on a patient in labor at Novant Health Forsyth Medical Center, then went to a game at Truist Stadium, assuming his patient had hours to go. But the labor sped up, and he got an urgent call from the hospital at the top of the seventh inning. “I jumped into my truck, broke a few traffic laws to get to the hospital, and the nurses threw a gown over my uniform while I ran down to labor and delivery,” Lewis says.

His patient pushed twice, the baby was born, “and everybody bonded perfectly,” he recalls. The new parents snapped a photo with their doctor-

coach; he was back at the ballpark for the ninth. The Turkeys won the game.

“I tell my sons,” Lewis says, “that if you can find a way to do what you love as part of your job, it makes life so much better.”

__________________________

How to Heal a Community Through Knitting

Sometimes an act of Pro Humanitate comes together naturally, as it did for Gretchen Zinn Seymour (’91) last year when a tragedy converged with her search for purpose.

On July 4, 2022, she was standing on the sidewalk in Lake Bluff, Illinois, with her husband, Jim Seymour, watching the town’s parade. Suddenly, the pager her husband wears as a volunteer firefighter “started blowing up — and his face just went white,” she recalls. They soon learned that two towns over, in Highland Park, a man had shot and killed seven people and wounded dozens during that town’s July Fourth parade. Among the dead were a married couple whose 2-year-old son was found wandering by himself.

A month later, with her younger daughter in college, Seymour was starting to consider what would come next for her when she noticed a little building that she walked by routinely on the way to a local coffee shop. After learning that it housed a nonprofit called Art Impact Project, which does art-based therapy with underserved populations, she knocked on the door and asked if its leaders had considered knitting, one of her passions.

Her inquiry turned into a project called “Knitting Communities Together.” The original idea was to recruit knitters (and those who crochet) from towns neighboring Highland Park to create a remembrance of the victims. The knitters met twice a week to create designs to wrap around trees in Highland Park’s Sunset Woods Park.

Gretchen Zinn Seymour (‘91), second from left, with Knitting Communities Together volunteers. Photo/Ann Marie Scheidler

But knitters from Highland Park soon joined them, and Seymour gradually realized that the process of creating their homemade tribute was even more meaningful than the result. “The magic happened in the room as we were knitting,” she says. “This woman who came every week had been sitting next to her sister when she was killed at the parade. The healing for these people, in knowing that we remembered what happened and that they could talk about it — it was incredible.” Friendships started to unfold among people from different towns and faiths. A few knitters who had rarely emerged from home since the pandemic got comfortable socializing again.

In the end, they created a bigger, more beautiful display than expected: Surpassing their goal of wrapping 10 trees, they covered 50. In September, they took up their needles together again, this time to knit hats and mittens for foster children.

__________________________

How to Make the Perfect Hot Dog

Why, you might ask, would a university magazine address such a frivolous-sounding topic as the humble hot dog? That’s easy. Wake Forest is home to one of the three anointed hot dog ambassadors in the USA.

Meet John Champlin (’06, MBA ’15). He works in Alumni Hall as director of engagement programs in University Advancement when he is not popping up at food trucks, dive bars and gourmet digs in search of franks, coneys, wieners and weenies. He is in his 10th year reporting his findings via his @TourDeFrank social media dispatches. From a Mexican-style dog wrapped in bacon and slathered in poblano lime cream to the dog with an Aloha theme of barbecue sauce and pineapple chunks to a Boston wine-bar dog covered in peppers, carrots and scallions, the Champlin chompathon over the years is nothing short of astounding.

Photo/Lyndsie Schlink

So are the stats. Champlin reports having eaten 673 hot dogs at 524 different hot dog joints with 213 family members, friends and strangers. “The goal? Not necessarily to find ‘the best,’” he says. “No, that’s incredibly subjective. As cliché as it is, the goal is to enjoy the ride.”

Experts noticed. In July the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council in Washington, D.C., named Champlin a 2023 Hot Dog Ambassador.

With the warning, “Divisive opinions ahead!” Ambassador Champlin offers advice for making the perfect hot dog.

The bun: Please, get something sturdy. For me, steaming a bun is … unwise. You’ve got to toast that bun. My favorite toasting method is melting butter — a “healthy amount,” as any Southern grandmother might say — in a pan, then putting buns split side down, (taking them) to a deep golden brown.

The meat: We don’t need to get into the nitty gritty of what’s in a hot dog. My choice is frequently going to be an all-beef brand that is grilled or sautéed. I prefer a broil over a boil.

The toppings: I firmly believe that everyone should love what you love. My go-to toppings are chili, slaw and mustard. Good hot dog chili should be richly beefy, not too watery, have a gentle spice and, for goodness sake, be bean free. Coleslaw should be creamy, a touch sweet and still have a bit of crunch. My nontraditional opinion is that spicy brown/deli mustard is the best with this combo. Wild card topping: french fried onions!

__________________________

How to Stop the Spread of Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories have abounded in the United States since George Washington was accused of trying to reinstate a monarchy, says Jarrod Atchison (’01, MA ’03), the John Kevin Medica Director of Debate and professor of communication. Atchison teaches students the argumentative features of conspiracy theories with case studies on 9/11, the MMR vaccine (given to prevent measles, mumps and rubella), President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and more in his class, Conspiracy Theories in American Public Discourse.

Conspiracy theories often break down into several themes, he says, including: scientific claims (Climate change must be a hoax because the winters are getting colder.), personal observations (How can you watch the Zapruder film and not believe that Kennedy was shot by two assassins?) and personal anecdotes (My friend told me something, so I believe it.). Conspiracy theorists often challenge traditional forms of authority, such as the media or science, and position themselves as protecting “victims.” (QAnon followers, for instance, often argue that they’re saving children, Atchison says.)

“Theorists will spout facts, and each individual fact may not be wrong, but it’s the extrapolation from the facts where we get to the conspiracy. It’s incredibly difficult to argue against conspiracy theories.” It’s often like playing “Whac-A-Mole,” he says. If you refute one argument, the conspiracy theorist will pivot to another round of facts to refocus the argument.

It’s almost impossible to change the mind of someone who already believes a conspiracy theory, Atchison says. Instead, focus on the people who haven’t made up their minds. “Imagine the Thanksgiving table, and one relative says, ‘I believe this conspiracy, and you should, too.’ Your goal is not to persuade that person that they’re wrong, because the chances you’re going to pull that off are very small. Instead, argue for the rest of the table to stop it from reaching a critical mass where your relatives are so moved that they take action to support it by donating money or voting for particular politicians.”

Atchison advises focusing on the credibility of the source, rather than arguing facts, to persuade your Thanksgiving guests to be skeptical of a conspiracy theory. Can the information be fact-checked? Does it come from a single type of source (anecdotes, social media, online videos)? “Slow the conversation down and utilize the most important tool you have at your disposal — your brain,” Atchison says.

__________________________

How to Get to Carnegie Hall

The old joke is right.

Larry Weng, assistant professor of piano, has shown that the best way to get to Carnegie Hall is to “practice, practice, practice.” He has performed there many times, most recently in May, to rave reviews: The New York Times once described him as playing with “steely power and incisive rhythm.”

Photo/Christina Soriano

But Weng didn’t exactly follow a traditional path. For starters, he didn’t discover the piano until he was 7 years old, “late for professionals,” he quips. A family friend gave his parents a hand-me-down upright for their Boston home, and Weng remembers being drawn to it right away.

Still, he wasn’t sure about piano as a career until he had gutted out a bachelor’s degree in economics at Columbia University in three years while also studying piano at The Juilliard School. That meant routine 12:30 a.m. to 2:30 a.m. practices on pianos in dorm lobbies far from residents trying to sleep.

Early on, Weng grasped what he sees as the key to everything that followed — his understanding that discipline is “one of the foundational, bedrock skills you need to be successful at anything,” he says. “Having the persistence to do something day in and day out is increasingly rare, and I talk to my students about it all the time. … Talent doesn’t show up unless you do.”

Photo/Lyndsie Schlink

He also finds motivation in challenges akin to climbing a mountain. Just 10 months into lessons, he asked his teacher to let him play Beethoven’s “Für Elise,” and she said he wasn’t ready. He kept asking at every lesson, until she finally relented on one condition: “I couldn’t tell her it was too hard,” he says. “It was such a satisfying thing to develop the skills to accomplish it.”

His second teacher fed his love for competing, which in turn sparked his passion for performing. “There’s something really wonderful about playing music for people, and it’s doubly wonderful when I can compete for something,” he says. He has won numerous international competitions, and his performances have taken him all over Europe, Asia and South America.

Critics frequently describe Weng’s style as physically and emotionally expressive: “When the motion matches the intent and the effect of the music, that’s when you communicate well,” he says. “You’re trying to get at the soul of the piece — what it’s trying to say.”

__________________________

How to Be a Demon Deacon Mascot

He’s the classiest, the most intelligent, the most suave, the most loved. He’s the hippest old-timer we know. He is the big man on campus, but he makes everybody feel like a somebody. He’s the Demon Deacon.

Why wouldn’t you want to be him?

Since the early 1940s, a lucky few students have gotten to suit up in the coattails and the confidence of our favorite oxymoronic mascot.

Students try out for the position on Wake Forest Athletics’ spirit team, just as cheerleaders and dance team members do. Typically, during the year, as many as three to six students take turns handling the Deacon’s busy schedule, even switching off each quarter during football games.

Photo/Ken Bennett

The men — and, yes, women — with the honor of being a Deacon bond over their love of Wake Forest, and, says one current mascot, their love of “making memories that make people love Wake.” They share stories of children’s faces lighting up after Deacon fist bumps and the laughter of older adults.

Almost like a secret society, Deacons keep their identities private until the long-awaited mascot reveal at the senior night football game. Finally, they can stop making excuses for why they can’t sit with their friends at games.

In the meantime, Deacons must wear the suit responsibly, especially in the age of social media; breaking character even briefly can go viral on Barstool Sports or Fizz. They carry the weight of Wake Forest’s image on their shoulders. Plus, that thick head gets heavy! For getting comfortable and dealing with temperature conditions in the suit, current and former Deacons shared tips:

Hydrate, starting two days before a game.

Face the wind to feel a breeze through the Deacon’s mesh eyes.

Play the “old man” card. While the Deac is more spry than most golden-agers, he can get away with wiping his brow and taking a seat every once in a while.

Launder with care to get rid of the suit’s less-than-gentlemanly aroma after a game. The head and shoulder covering, pants and gloves are machine washable. (And yes, that means that the suit is washed in dorm laundry rooms across campus.) Careful with the jacket, though — dry clean only.

Wear long socks when strapping the 15-inch-long kicks over your feet. One current Deacon has an ankle scar from wearing low socks for a whole game.

It’s worth the smells and the scars, though, for the magic. “This summer I was standing on top of the (baseball) dugout, and I was dancing like I was just in my room alone in front of the mirror,” a current Deacon said. “I was having the time of my life.”

__________________________

How to Propagate Pro Humanitate

Chuck Neaves (’79, JD ’82, P ’12) and Susan Templeton Neaves (’80, P ’12) established their mission field in the red clay soil of Wilkes County, North Carolina.

Chuck started a small garden in 2010 with the idea of giving away vegetables to whoever needed food. The plot didn’t produce much that first year, but today the Fellowship Garden produces about 10 tons of food and helps feed hundreds of people a year.

“A few seeds and plants sown 14 years ago have grown to provide so much for so many,” says Chuck, a retired chief district court judge turned farmer. “The garden is one way we can ‘love our neighbor’ in our little corner of the world,” Susan says. “Find what you love, and use it in a way that can help other people.”

The Fellowship Garden occupies 3 acres of a former vineyard outside Elkin, North Carolina. (An Elkin lawyer lets the Fellowship Garden use it at no cost.) It provides fresh produce nearly year-round — beans, cucumbers, potatoes, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, squash, watermelons and more — to about a dozen community partners, including churches, a homeless shelter, a food pantry and a men’s rehabilitation house.

It takes a community of volunteers to run the garden, Chuck says. “Fellowship” in the garden’s name comes from the fellowship among the volunteers —

who are from different churches and of various ages and ethnicities — as they work side by side and bond during breaks over homegrown tomatoes and fresh zucchini bread.

About 15 to 20 volunteers, mostly retirees, regularly work in the garden, with Boy Scouts, church groups and high school agriculture students helping occasionally. A beekeeper tends hives on the property; proceeds from honey sales are plowed back into the charity. Wilkes Community College donates seeds and grows new plants in its greenhouse for the garden. The Neaves’ church, First Baptist Church in Elkin, provides funds for supplies.

Their parents instilled in them the value of helping others long before they came to Wake Forest and learned about Pro Humanitate, Chuck and Susan say. “We both grew up with parents who were all about helping their neighbors in any way they could,” Susan says. “Chuck’s vision of planting with a purpose all those years ago has yielded blessings in abundance.”

__________________________

How to Talk to Your College-Age Daughter (for Dads)

When daughters encounter struggles, many fathers jump in to help right away. But Professor of Education Linda Nielsen, who has spent decades researching father-daughter relationships, has ideas for more effective ways to communicate. She’s such an authority on the subject that toymaker Mattel Inc. consulted her on ways dads can bond with their daughters while playing with Barbie dolls.

Fathers have been socialized to fix problems, so their impulse to act is “loving, it’s nurturing, it’s well-intended,” Nielsen says. But she advocates a different, more effective approach using “The Three H’s”: Ask your daughter if she wants to be hugged, heard or helped. Often, daughters want all three, in that order. First, your daughter may want to be consoled and comforted — without getting any advice. Next, she may want you to listen while she vents or cries, again, without offering advice. After that, she may be ready for advice. But before you dive in, ask if she’s ready for it yet.

About that advice: Don’t try to solve her problems for her, Nielsen advises. Instead, try to help her find ways to navigate obstacles on her own. “Dads should be preparing the child for the road instead of preparing the road for the child,” she says.

Try carving out an hour or two during family visits to campus and on breaks for the two of you to spend time alone on a father-daughter walk or coffee date. You could also take the initiative to text, call, Zoom or send a funny card. “These are the four years when both of you have the chance to strengthen your communication skills with each other,” she says.

Nielsen suggests using that one-on-one time to share stories about your own college struggles. Open up about the tough times and how you got through them — not just your academic problems, but the challenges of dating, roommates and figuring out your future. “Let her see that you’re not Superman with special powers that allowed you to escape the disappointments, frustrations and pains that she faces,” Nielsen advises. “You’re just a guy wearing a red cape without any superpowers.”

__________________________

How to Sail Around the World

Eric Bihl (’10) and Kennon Jones (’10) set sail in January 2018 to circumnavigate the globe. By the time they returned to the United States in June 2020, they had sailed about 30,000 nautical miles with stops in about a dozen countries, including French Polynesia, Vanuatu, Indonesia and South Africa.

Eric Bihl (‘10), left, and Kennon Jones (‘10) on board the Temujin

They have a bit of advice for anyone considering following them: Don’t say “one day.” Pick a day and stick to it.

Bihl and Jones met at Wake Forest rushing Sigma Pi fraternity. After graduation, the two buddies frequently sailed along the East Coast and hatched the idea of an around-the-world trip. “To spend time doing what you love, to see the world, to challenge yourself,” Bihl says, recalling their inspiration. “Is this possible? Can we do it?”

They traded in their smaller boat for a 34-foot sailboat named Temujin and took short jaunts to make sure the boat was ship-shape and “to make sure we wouldn’t kill each other,” Jones says. “Make sure you get along with the other person, because there’s not a whole lot of space to hide.”

The Temujin in Indonesia

American Samoa

After bidding farewell to family and friends, they sailed down the East Coast. After passing through the Panama Canal, there was no turning back. They packed all the water, rice, beans, potatoes, canned goods and eggs they could carry with them. They picked up fruits and vegetables at port stops and became good fishermen. Bihl missed having cold Gatorade on a hot boat; Jones missed Chick-fil-A. Their longest stretch at sea was 34 days from Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean to the U.S. Virgin Islands, when many ports were closed because of COVID-19.

Bihl and Jones in Namibia

Before their trip, Bihl was a salesman for a winery, and Jones worked at the U.S. State Department in Washington, D.C. The trip “changed the trajectory of both of our careers,” Bihl says. He learned more about the wine industry working for a winery during a long layover in New Zealand. He is now an assistant winemaker for a small winery in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he and his wife, Lauren Leifeste Bihl (’10), live — “ironically,” he notes, “pretty far from water.”

Jones lives in St. Thomas and captains the Altesse, a charter catamaran that sails the U.S. and British Virgin Islands. “Apart from the obvious career change, for me this trip underscored that you don’t need a lot of things and stuff that we tend to accumulate,” Jones says. “It is the memories you make that are the most important.”

Jones and Bihl in Suwarrow Atoll in the Cook Islands

__________________________

More How-to stories:

How to:

How to:

How to: