Get the Most from Mentoring | Think about Privacy in the Age of Surveillance | Have Difficult Conversations | Cement Your Deacon Friendships | Reduce the Stigma Around Mental Health Issues | Make the Most of Your Nose | Play the Carillon | Get Back to Nature in Death | Overcome Business Challenges for Women | Explore the Tunnels Using a Robot | Rewire, Not Retire | Widen Opportunity

__________________________

How to Get the Most from Mentoring

Having a growth mindset is one of the two most important skills you can develop over the course of your career, says Allison E. McWilliams (’95). The other is the ability to build relationships with people who support you as you grow and achieve your goals.

McWilliams, assistant vice president of mentoring and alumni personal and career development, returned to her alma mater in 2010 to help alumni, students, faculty and staff build relational skills. She also writes “Your Awesome Career,” a blog for Psychology Today about the personal and professional development of young adults.

Photo/Ken Bennett

Mentorship is not the only type of relationship you’ll build during your career, but it’s one of the most important. You will likely have a number of mentors, and mentees, over time as your needs change, so mentorship doesn’t have to mean finding that one “be all, end all” person.

Here are McWilliams’ tips for making the most of mentoring relationships:

Set goals. Mentees should do the work of setting and achieving their goals. The mentor “should never care about your growth and your development more than you do,” McWilliams says.

Be committed and present. Show up on time. “Hold that time sacred, and be prepared and there in the conversation,” she says. Mentees, think through questions in advance. Mentors, be intentional as you consider a commitment to a potential mentee. If you might have to back out of the relationship, it is better to say no and help the mentee find another person instead.

Give and receive feedback. A mentor can help and encourage a mentee by offering insights into the mentee’s strengths and growth areas. But before you do, McWilliams says to consider, “Are you doing it to help them make progress on those goals? … Or is it just an opportunity to sit on your soapbox and give feedback?”

Mentees should be open to learning from feedback, but so should mentors, who can grow in knowledge about shortcomings and biases.

Be grateful. Mentees, always say thank you.

McWilliams believes the fundamentals of great mentoring relationships make all our relationships better. “Ultimately, it is about showing up and being present with another person,” she says. It’s about “building trust and rapport with another person, asking great questions and listening. … It’s about providing encouragement to one another, right? If we did that in all of our relationships, … everything wouldn’t be perfect, but it would take care of a lot of things.”

__________________________

How to Think about Privacy in the Age of Surveillance

Put away the trench coat and fedora. You probably don’t need to be on guard for computer espionage the way Shane Harris (’98) does, but you might want to heed his tips.

A staff writer covering intelligence and national security at The Washington Post since 2018, the award-winning Harris worked a similar beat at various publications after the 9/11 attacks. He has written books about national security, the rise of the surveillance state and spies.

Harris says he has experienced at least two instances in which foreign governments — Russia and Iran — tried to access his computer, communications and emails. As part of a broader effort in 2016, a Russian group was sending “spearfishing emails designed to look like they come from someone you know or to appear legitimate in some way,” he says. The trick lures the receiver into clicking on the link or file in the email, which then downloads spyware or malicious viruses onto the computer. Harris didn’t fall for it.

Vigilance about digital security is part of the job: “You just always assume that there is some organization that would be interested in accessing your communications and getting access to the people you know and what they’re telling you,” he says.

For security for anyone, Harris advises the first and most important step is two-factor authentication whenever you can set it up. Think about logging into your bank account. You typically need more than just a username and password to get in. Even Harris’ newsroom insists on such a system internally.

For sensitive texts and phone calls, Harris uses encrypted applications. In his case, it’s Signal. The app wins the vote of confidence for “journalists’ safety” from Reporters Without Borders, a nonprofit with a mission to defend independent journalism.

Sometimes Harris covers his camera on his computer. A Band-Aid can suffice. He’s careful about using social media. Traveling overseas on a reporting trip, he won’t post on Instagram or X and won’t allow his tweets to be geolocated to pinpoint his locations.

Try to shift to passphrases instead of passwords, Harris says. He points to the Electronic Frontier Foundation for guidance on protecting online privacy. He also advocates employing a password manager to keep passwords secure and generate hard-to-guess passwords. He uses the Keeper app.

In general, beware of the “misleading information swirling around social media,” just as Harris’ intelligence sources are. “It requires that consumers of news have to be so much more judicious, discerning and skeptical,” he says.

__________________________

How to Have Difficult Conversations

Nelly van Doorn-Harder, professor of Islamic studies, has a world of experience, literally, in observing how people with conflicting views and beliefs can find common ground.

A native of the Netherlands, van Doorn-Harder earned degrees in theology and Middle Eastern studies and a doctorate in religious studies, focused on women in the Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt. She set up a refugee program in Cairo for both Christians and Muslims from several African countries and Romania. She taught Islamic studies in the Netherlands and Indonesia, a primarily Muslim country where she created an interfaith dialogue program. She is married to an American and came to Wake Forest’s Department for the Study of Religions in 2018.

In her refugee work with Somali Muslim and Ethiopian Orthodox refugees, she began seeing the need for interfaith conversations.

The right environment is key for people to get to know each other as individuals with their own stories and personalities rather than as “other” or “enemy.” This opens people to trusting each other and talking about deeper issues without anger or fear, van Doorn-Harder says. People more easily connect when they face similar challenges, she says.

A celebration of the Diwali and Eid holidays in Benson University Center in 2018

Creating a safe space is fundamental. The ingredients are basic. First, people need a safe physical place to meet. “Our agency was connected with a church. Churches and mosques were one of the few places that allowed for humanitarian activities, … for being able to do something human together,” she says.

Food carries that magic. “They can understand each other’s food patterns and what they eat. Actually, people became very excited (about having meals together). So we found a little fund to give people grocery money so that they could make their own, an Ethiopian dish or a Somali dish to share. Sometimes it was a Western dish. Everybody loves pizza. … It opens up conversations.”

The next step was to introduce the topic of religions, van Doorn-Harder says, looking for places where beliefs overlapped. For instance, groups would look at how John the Baptist is portrayed both in the Bible and in the Quran, where he is venerated by Muslims.

“One of the tools of hatred is to make sure that you don’t meet the other side. And that is what we see in a lot of communities…,” she says. “You can vilify people as long as you don’t know them.”

Differences can lose their venom when “you actually get to know someone from the group that you hate or despise so much.”

__________________________

How to Cement Your Deacon Friendships

We always love hearing stories of the many Wake Forest friend groups that have continued after graduation day.

But what you don’t always see from the outside are the effort and commitment required for friendships to stand the test of time. One such group that knows what it takes adopted the name “The Wild Women of Wake Forest,” 14 women from the class of 1975 who met freshman year.

“It is those bonds that we’ve formed,” says Janice Kulynych Story, one of the Wild Women who shared the group’s advice for alumni who want to retain, or reignite, their college friendships. “They’re so precious to all of us that we want to keep it going.”

It’s never too late to reinvigorate your college friend group. The Wild Women rarely gathered during graduate school, moves, new marriages and children. It wasn’t until 2002 that Vickie Cheek Dorsey invited everyone to Cashiers, North Carolina, for a weekend. (Sometimes it takes one person to stand up and get the group organized, Story says.)

During their now regular trips, they shop, cook, hike and enjoy one another’s company. Night owls stay up talking until 1 a.m.; early birds drink coffee in their bathrobes. Last year, they threw themselves a 70th birthday party at the beach, complete with champagne and cake. The women make every effort to attend each gathering, freeing up their calendars if at all possible.

Back row, from left: Leslie Hoffstein Stevenson (‘75), Kathleen Brewin Lewis (‘75), Gail V. Plauka (‘75), Norma Pope (‘75, P ‘12), Lynn Killian (‘75), Vickie Cheek Dorsey (‘75, JD ‘78, P ‘08, ‘15), Janice Kulynych Story (‘75)<br /> Front row, from left: JoAnn Mustian (‘75), Jennie Bason Beasley (‘75, P ‘07), Cindy Ward Brasher (‘75, PA ‘76), Jan Rosche Aspey (‘75), Becky Sheridan Williford (‘75, P ‘08, ‘13)

Their effort goes beyond reunion trips. “Whether it’s a pat on the back, whether it’s a hug, whether you’re sitting there crying your eyes out with a friend because something tragic has happened, I think it is part of it,” Story says. When one woman was going through a divorce, another went without hesitation to stay with her for a few days.

The Wild Women are an opinionated bunch who mostly get along. (They recommend avoiding politics.) “No judgment,” Story says. “None of us are perfect, and we all realize that.”

They have exchanged long email chains for years along with cards, phone calls and letters, and now they share funny Instagram posts, too.

Yet, it seems like one of their keys to success is spending time in person.

“Nothing can replace just being right there, sitting at a table and saying, ‘These are my college friends. And this is 50 years later,’” Story says. “It’s pretty phenomenal.”

The Wild Women of Wake Forest:

Jan Rosche Aspey (’75), Jennie Bason Beasley (’75, P ’07), Cindy Ward Brasher (’75, PA ’76), Vickie Cheek Dorsey (’75, JD ’78, P ’08, ’15), Lynn Killian (’75), Kathleen Brewin Lewis (’75), Deborah Roy Malmo (’75, MBA ’79), JoAnne Green Marino (’75, P ’05), JoAnn Mustian (’75), Gail V. Plauka (’75), Norma Pope (’75, P ’12), Leslie Hoffstein Stevenson (’75), Janice Kulynych Story (’75), Becky Sheridan Williford (’75, P ’08, ’13)

__________________________

How to Reduce the Stigma Around Mental Health Issues

Juliet Lam Kuehnle (’06) is a therapist who goes to therapy, takes medication for her mental health and does not hesitate to talk about any of it.

“The more we can own our vulnerabilities and be authentic, it gives permission for others to do the same,” says Kuehnle, who lives in Charlotte. “We all have mental health, so I talk about it as kind of the ultimate trifecta — physical health, spiritual health, mental health. And to me, mental health is foundational to all of those.”

She uses platforms beyond her practice to aim squarely at the misconceptions about mental illness and knock them down. Her book is “Who You Callin’ Crazy?!: The Journey from Stigma to Therapy,” and her podcast is “Who You Callin’ Crazy?!” She seeks to normalize the dialogue around mental health and erase the stigma so that “we can all own our humanness and maybe even proudly claim, ‘Yep, I go to therapy!’”

Her tips for reducing the stigma? First is to have an awareness of it — from the “public stigma” often attached as a label to those with mental illness to the “self-stigma” that manifests in internalized shame. It’s important to be aware of different categories of stigma to stop perpetuating the behavior, she says, and to speak up when others make negative comments about mental illness.

Second is to pay attention to language. That’s the point of her catchy book title. “It’s like taking power back,” she says. It’s also about listening for language that minimizes or dismisses mental health issues. An example: “Don’t be so OCD!” is tossed around flippantly on social media, she says, without commenters showing they have clinical knowledge about the nature of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. (It’s described as a long-lasting disorder in which a person has uncontrollable, recurring thoughts and/or behaviors that he or she feels the urge to repeat over and over.) In other words, know the facts.

Third is to practice vulnerability, which gives others permission to do the same.

The pandemic underscored the need for addressing mental health issues, Kuehnle says. As a “stigma buster,” she hopes to turn “the moment into a movement.” And she continues to urge people to seek help when they need it. “You’re not the only one feeling whatever it is you’re feeling. Reach out to share what’s going on, to ask for support. There’s no need to walk through it alone.”

__________________________

How to Make the Most of Your Nose

The world once surrounded humans daily with Mother Nature’s perfume, but modern society encloses many of us in sanitized homes, work spaces and cars. Our goal often is to eliminate bad odors rather than experience pleasant ones. Evolution certainly favored those who could smell a forest fire or rotten eggs, but good smells have purpose and meaning, too.

Jude Stewart (’96) offers ideas for pumping up our neglected olfactory sense in her book, “Revelations in Air: A Guidebook to Smell.” It explores the amazing nature of our olfactory super powers, including evoking memories in a way no other sense can match. She is a writer in Chicago whose Stewart + Company creative agency specializes in content strategy and development.

A recent study showed a 226% increase in cognitive capacity for older adults after six months of fragrances wafting through their bedroom for two hours a night. “So, we have the science,” Stewart says. “The qualitative argument is about mindfulness.”

Smell is fleeting and requires physical presence, she says. “You’re pinning yourself in a moment, … not doing anything else, … and we need more of that in life.”

Stewart suggests sniff-strengthening exercises:

• Keep a daily journal of smells and focus on precise language to heighten awareness. Your smell will improve.

• Crush materials in your fingers to coax airborne smells from solid substances. Water unlocks smell, so use a spritzer. A moistened paper towel inside a glass jar (impermeable, so it doesn’t add any smell) will amplify the scent. Notice smells when it rains or the humidity is high.

• Movement sends more scent molecules into the air, and your own movement helps you capture them. Move your head back and forth, since one nostril often is more sensitive to smell than the other. Or wave the source under your nose, as perfumers or sommeliers do.

• Play a game, inspired by olfactory artist Maki Ueda. Have a friend hide smells around a room so you can search for them blindfolded. “You could blindfold yourself,” Stewart says, “(but) that’s dangerous.”

• Like actors who use scents to create memory and emotion for a scene, have a scent around you “that makes you feel like a million bucks.”

__________________________

How to Play the Carillon

When you enjoy the alma mater or a Beatles classic or even a Bruno Mars tune coming from the carillon in the Wait Chapel tower, remember one thing: “People often don’t realize there’s a real person up here,” says University carillonneur Anthony Tang (’11), who learned to play the carillon when he was a student.

Photo/Lyndsie Schlink

The carillon is played from a keyboard with two rows of 48 wooden batons, or keys, similar to a piano, and pedal keys. Carillonneurs — for whom previous experience playing the piano is a plus — “strike” the batons with the pinky-finger edge of a fist. It doesn’t take much force to push down a baton, but it does take concentration and coordination. Varying how hard and how fast a key is hit changes the mood, tone and sound.

“You can really emote,” says Tang, who is director of strategic development in Wake Forest’s University Advancement office. “It’s not like a computer where it’s the same every time.” Tang has mastered his playing style so that his hands glide across the keyboard, often using his fingers instead of his closed hands.

The small carillon room is sandwiched between the tower clock room and the space where the 48 bronze bells hang on a multilevel steel framework. Officially the Janet Jeffrey Carlile Harris Carillon, it was donated by the Very Rev. Charles Upchurch Harris (’35, L.H.D. ’80), in honor of his wife, Janet, and installed in 1978. The bronze bells, cast in Annecy, France, range from 28 pounds to 4,397 pounds and collectively weigh about 12 tons. Only three of the largest bells actually swing.

Photo/Ken Bennett

Five of the largest bells can be programmed from the carillon room or Tang’s phone to automatically play the funeral toll (striking one bell slowly over long intervals), the Westminster chimes melody (to mark the hour) and the celebration peal (familiar to anyone who’s rolled the Quad). Otherwise, it’s Tang or a student playing the carillon.

Tang’s favorite songs to play on the carillon (after the alma mater and fight song, of course) are:

1. “The Music of the Night” | From “The Phantom of the Opera”

2. “My Way” | Frank Sinatra

3. “Leaving on a Jet Plane” | John Denver

4. “Amazing Grace” | John Newton

5. “What a Wonderful World” | Louis Armstrong

“Every time I come up here is a special moment,” Tang says.

__________________________

How to Get Back to Nature in Death

Tanya Marsh, senior associate dean and professor of law, sees a death-care revolution in the United States when it comes to what happens to our remains. Don’t be surprised if you hear about “human composting.” It really is a thing, and Marsh’s students helped make it happen.

“For several generations, people were just happy to defer to the authority of the death-care industry,” says Marsh. She created the first course in a U.S. law school on funeral and cemetery law.

Before the Boomer generation, the question wasn’t whether you would be buried, but what kind of casket you would buy and what day to have a viewing, Marsh says.

But more people began looking for less expensive and more flexible options. Communities realized cemeteries take up valuable land. In 1972, fewer than 5% of Americans chose cremation, which had been legal for 100 years, Marsh says. By 2015, the rate had climbed to 50% and will soon exceed 70%, she says.

Younger people want even less environmental impact than cremation, which uses fossil fuels. “Green burial” is catching on as an option, even though it has been the predominant method for most of human history, she says. Americans didn’t embalm bodies until the Civil War, and “traditional” funerals only became customary during World War II, she says.

Clients of Recompose can choose to donate some or all of the soil created by human composting to revitalize conservation land in the Bells Mountain wilderness in Washington.

She notes “the irony of a minister standing over a grave and saying, ‘Ashes to ashes, dust to dust,’ and then putting an embalmed body inside a steel casket inside a concrete box.”

The speed at which states and the public have embraced new technologies allowing, also ironically, a return to nature “is unbelievable,” Marsh says. Besides cremation, options include green burial of bodies without embalming in biodegradable coffins, a shroud or laying bodies directly into the earth. Another option is “flameless” or water cremation, chemically reducing a body to fluid and drying the bones to ashes. The newest is human composting, a process created by entrepreneur and designer Katrina Spade. She founded Recompose in the state of Washington in 2017.

Marsh’s law students researched and gave Spade memos on the path to legalization in each state, and at least seven states have enacted statutes allowing human composting.

The Recompose composting vessel turns human remains into soil.

Just putting a body into the ground decomposes it, but that’s not composting, which involves sealing a body in a container with organic matter, the right soil microbes, oxygen and regular mixing. After a couple of months, the facility crushes the remaining large bones. After more composting, the result is pure, nutrient-rich soil, safe for a garden or just a resting place in nature. The service at Recompose costs about $7,000, on par with a typical funeral.

Some people react to this newest approach “with ‘Ick, that’s really weird,’” Marsh says. But others are intrigued: “They say, ‘That’s amazing. That’s great. It’s so natural.’”

__________________________

How to Overcome Business Challenges for Women

Jennifer Scherer McCollum (’91) still remembers the thrill she felt as a young public relations manager angling to get high-profile coverage for The Coca Cola Co.’s sponsorship of the 1996 Olympic torch relay — and the devastation she felt when an Olympics official described her as “a cupcake with a razor blade inside.”

After switching gears at Coke to internal consulting, she realized that her experience was a textbook example of the “double bind” that women face professionally as they toggle between expectations for the masculine stereotype of the ideal leader (forceful, assertive, competitive) and the stereotype of the ideal woman (warm, caring and collaborative).

Now it’s a key anecdote in her new book, “In Her Own Voice: A Woman’s Rise to CEO,” which provides advice on professional advancement for women and organizations that could use more gender equity in management. McCollum is CEO of Linkage Inc., a global leadership development firm that’s part of SHRM (Society of Human Resource Management). For her book, she draws from more than 25 years of Linkage’s research.

The “overarching hurdle” most women face is their own “inner critic,” meaning the critical voice in their head that’s judging and doubting themselves and possibly others, she says. McCollum recommends three ways to start quieting self-doubt.

First, focus on clarity, “asking what I want with my career and my relationships,” she says. “Most women say, ‘I have never thought about it,’ or ‘I want my team to be effective.’ But what do you want?”

Second, women should stop trying to prove their value by simply working hard and hoping others will notice. Instead, McCollum encourages women to learn to delegate rather than taking on extra tasks. Delegating allows them to “focus on the work that aligns with their strengths and passion.”

Third, learn to make the “ask” — not just for pay, but for resources, flexibility and other benefits that clear your path, she says. If you’re refused, negotiate instead of retreating.

Companies have work to do as well. Research shows that women leaders perform better and stay longer at organizations that effectively use four levers: culture (Do women feel valued?), people systems and processes (Do women have an equal shot?), executive action (Are executives truly committed to supporting women beyond saying the right things?) and leadership development (Do women have access to formal training, stretch experiences and coaching?).

“Women can do the work themselves, but they can’t fix the overall system,” McCollum says. “Getting more women into leadership will take all of us.”

__________________________

How to Explore the Tunnels Using a Robot

The maze of utility tunnels that run underneath campus may intrigue Wake Foresters imagining something out of Harry Potter — but the tunnels are quite dangerous. (These are not the ones you remember using to go between dorms in the 1970s.) A person entering the confined space finds heat, standing water, cables with thousands of volts and pipes releasing high-pressure steam.

Highly specialized utility maintenance teams regularly face these conditions for their work, which can include fixing steam lines or inspecting systems to avoid disturbances during campus construction. And there’s a high cost. Employees entering the tunnels deal with physical stress and undergo extensive training to navigate the tight spaces.

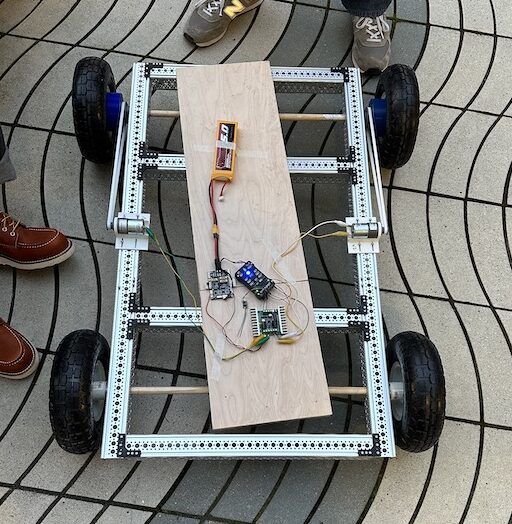

Nick Golden, environmental specialist in the University’s Office of Environmental Health & Safety, mentioned the challenging conditions to engineering students. They hatched an idea: a remote-controlled robot that could explore the tunnels, reducing the risk for employees.

Last year, students in the Robotics Club created a prototype tunnel robot. Then-juniors Shelby Horth, Benicio Costales and Farrell Fitzpatrick spent hours outside of class in Wake Downtown’s Innovation Studio and WakerSpace on Reynolda Campus, brainstorming and testing out ideas. They had a real-world client — the EHS office — and worked with Golden to understand what utility maintenance teams need.

Costales and Fitzpatrick, engineering majors, selected every element of the robot, from the metal chassis to the motor to the wheels. They managed a budget and got creative, using cardboard and a laser cutter to create a body for the top of the prototype.

In background, from left: Paul Hysell, associate director in the Office of Environmental Health & Safety, with students Shelby Horth, Farrell Fitzpatrick and Benicio Costales

Horth, a computer science and applied mathematics major, programmed a miniature computer that receives a wireless connection to steer the robot and transmit data. The team chose what looks like a handheld video game controller to steer the robot.

When team members were stumped, they asked for guidance from their engineering and computer science professors.

“We get to have fun together,” Horth says of the team, “but we’re all very driven and goal-oriented. … We get stuff done.”

Finally, the team tested the robot prototype in “the breezeway,” a tunnel area under Wait Chapel big enough to stand up in. It worked!

They used what they learned from the prototype to plan a smaller, more efficient robot for EHS, and this year, they are building it as part of an engineering capstone project. A skateboard motor would power the 15-by-20-inch robot, which is designed to collect tunnel data using a 360-degree camera, a gas meter and a thermal imaging camera. Using the robot’s reconnaissance, the maintenance teams will be able to do their work with less risk.

__________________________

How to Rewire, Not Retire

Many people will spend more time in retirement than they did working. Having a fulfilling retirement, rather than just filling time, takes planning, says author Rick Miners (’68).

“The thing that people miss is that they think retirement is one single block of time, like one long vacation, and it’s not. It’s a series of ages and stages,” he says. “It’s not a question of what’s right or wrong, but what’s best for you.”

Miners, 77, and his wife, Jeri Sedlar, 73, are life coaches and co-authors of “Don’t Retire, REWIRE! 5 Steps to Fulfilling Work that Fuels Your Passion, Suits Your Personality and Fills Your Pocket.” They wrote the book after finding in their work that most people understand the importance of financial planning, but fewer understand the need for life planning.

Retirement is going away from something — full-time work — but what are you moving toward? Don’t assume you’ll figure it out as you go along. Change your mindset to “rewiring” to figure out how you’re going to make the most of your next act, he says. That could include continuing to work but cutting back on your hours, taking a part-time job, starting a new career or volunteering.

Pursue your passion, whether it’s traveling or learning to paint or play the piano. “If you have a dream that’s never been realized, this is a point where you can pursue it, but you have to make the effort to do it,” Miners says. “People who don’t have interests are cast adrift in retirement. They don’t know how to spend their time. They can get depressed very easily.”

Take a “driver’s test” before you retire to figure out what drives you: Why do you work, beyond a paycheck? To make a difference? To have structure? To be creative? To learn new skills? To mentor others? Once you know what makes you tick, use your drivers to identify the opportunities that you’ll find most fulfilling, says Miners, who offers 85 drivers in his book. If, for instance, you crave recognition and power, you’re probably better off serving on the food bank’s board of directors rather than volunteering in a soup kitchen.

Use your imagination and dream big. Ask yourself to frame your future this way: “One of these days, I’ll …” It’s OK if you find out that painting is not for you, or that side gig doesn’t work out, Miners says. “Sometimes failure will lead to something totally different that you never expected, and that might be the right path.”

More at dontretirerewire.com

__________________________

How to Widen Opportunity

Former Wake Forest and professional soccer player Amir Lowery (’04) is using the game he loves to create opportunities on and off the field for young players from low-income families and underserved communities.

Lowery is executive director of Open Goal Project, a nonprofit he co-founded in 2015 in Washington, D.C., to level the playing field in a sport dominated by a “pay to play” model. But its mission is about much more than a game, he says. It’s about helping children and teenagers grow and develop.

“We’re striving to position our student-athletes to have a better life and encourage them to pursue higher education or develop necessary skill sets as they move into the workforce and into the next phase of their life,” Lowery says. “The game is a powerful vehicle for youth enrichment.”

Photos courtesy of Open Goal Project

An All-ACC second team selection at Wake Forest, Lowery played professionally for eight seasons before moving back home to Washington. Coaching youth soccer, he noticed a lack of racial and socioeconomic diversity because of the high cost of soccer camps and youth travel teams.

He started Open Goal to make youth soccer more accessible and diverse. All its programs are free, funded by grants and donor contributions. “No matter how much money their parents have, what their transportation situation is or whether their parents can speak English, we make sure that we bridge all those gaps and afford kids the opportunity to play at a high level,” he says.

Initially, Open Goal sponsored talented players from low-income families to play on travel soccer teams and offered free camps and clinics to help other players compete for spots on travel teams. In 2019, Open Goal expanded to reach more young people by launching its own travel program, the District of Columbia Football Club (DCFC), which has more than 150 boys and girls on eight teams.

DCFC eliminates financial and other barriers that often exclude kids from traditional teams, Lowery says. Practices occur near public transportation. Matches are played against clubs in Washington, Maryland and Virginia to avoid travel costs. Coaches speak English and Spanish. Open Goal also offers college counseling, SAT prep and youth development workshops.

“The game has had a tremendous impact on my life,” Lowery says. “So many of the things (you learn) translate off the field. Teamwork, discipline, confidence, resilience — all those qualities have a tremendous benefit for our kids, whether they pursue a career in soccer or any other field.”