Sona Tatoyan (’00), a Syrian-Armenian-American writer and actor, traveled from her home in Los Angeles to war-torn Aleppo, Syria, in 2019 on a mission: to save her great-great-grandfather’s 100-year-old Karagöz shadow puppets. He had taken the puppets with him when he and his family fled present-day Turkey to Syria in 1915 to escape the Armenian genocide.

Tatoyan hoped she would find a few surviving puppets in the attic of her abandoned ancestral home. Instead, she found more than 180 puppets in a wooden trunk. The puppets inspired her to create “Azad (The Rabbit and the Wolf),” a multimedia theatrical experience that she presented this month in Scales Fine Arts Center.

"I found a magic box in a war zone. Those puppets ... were just hanging out until it was time for us to meet."

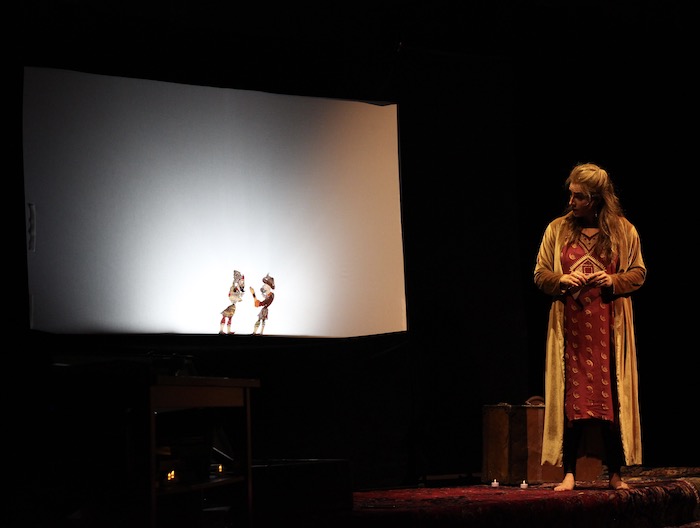

The puppets were used by her great-great-grandfather, Abkar Knadjian, in puppet shows as he traveled around the Ottoman Empire and later Syria. Karagöz puppet shows are a traditional form of storytelling — “cinema before cinema,” Tatoyan explains — that are still performed across the Middle East. They employ brightly colored two-dimensional puppets, a screen, lighting and shadows.

“(The puppets) sat in the attic for a hundred years, witness to a whole family’s life,” Tatoyan says. “Then the crazy great-great-granddaughter finds them and liberates them. … Those puppets are performing again. This is a quantum collaboration with my great-great-grandfather. I’m taking his art and continuing the story of what happened after him. It’s like this endless, great circle.”

Sona Tatoyan performs "Azad" on the Tedford Stage in Scales Fine Arts Center.

Tatoyan presented “Azad” (“free” in Armenian), directed by Jared Mezzocchi, during a visit to campus as artist-in-residence. It weaves together Tatoyan’s family story, the Armenian genocide, the Middle Eastern folktales of “One Thousand and One Nights” and the plight of Osman Kavala, a modern-day imprisoned Turkish human rights activist. The puppets help her along her journey from her childhood in Indiana to her college days at Wake Forest (and the influence of Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77) to her discovery of the puppets in Aleppo, as she overcomes personal trauma, accepts her heritage and heals ancestral wounds from the Armenian genocide.

She has also presented versions of “Azad” at Harvard and the University of Connecticut and in Berlin and Los Angeles. Performing at Scales was particularly meaningful, she told the audience, because she performed on the same stage when she was a student, and the late President James Ralph Scales had helped her father, Syrian immigrant Dr. Krikor Tatoyan (’73, MD ’77), get into medical school. (Her father is a surgeon in Los Angeles.)

Taatoyan never met her great-great-grandfather, but like him, she is a storyteller. She has created a nonprofit, Hakawati (storyteller in Arabic), to tell the stories of marginalized communities.

Wake Forest Magazine’s Kerry M. King (’85) caught up with Tatoyan during rehearsals for “Azad.” Excerpts have been condensed and edited for clarity.

About 40 of Tatoyan's great-great-grandfather's 100-year-old Karagöz shadow puppets and newer puppets appear in "Azad."<br /> <br />

King: You told me as you walked into Scales that you hadn’t been back to Wake Forest in 20 years. You became very emotional when you saw (theatre professors) Mary Wayne-Thomas and Sharon Andrews. (Theatre professor Cindy Gendrich helped arrange Tatoyan’s visit.) Were you expecting that?

Tatoyan: It feels really profound to be here again after so long, and after how pivotal and seminal, formidable, both Wake Forest and my experience as a theatre (and English) major has had on my life.

KK: What did you want to do when you came to Wake Forest?

ST: I’ve wanted to be a storyteller since I was 8. This is where I feel alive. It also intersects with things in the world that are not spoken about, that are hidden for various nefarious purposes and reasons. This thing I love to do is a way to talk about those things, not from a space of a cerebral lecture or government policy, but from a place where people can be moved and connect to their common humanity, which may actually provide a chance for something to change.

Sona Tatoyan on the Tedford Stage. All photos, unless otherwise noted, by Sydney Bowman and Julian Glasthal, Program for Leadership & Character. <br /> <br />

KK: You spent many childhood summers at your mother’s family home in Aleppo, but you didn’t know about the puppets until much later, right?

ST: I had always heard that Abkar Knadjian was a hakawati, which means storyteller in Arabic. In the early 2010s, I started asking, “Well, what did he do?” “Oh, he played with these figures called Karagöz.” My uncle, who fled from Syria to Armenia during the (Syrian civil) war, told me, “By the way, we still have those puppets. They’re in a trunk in the attic.” I said, “What?! You left them in the attic!” They survived the Armenian genocide and now they’re in another war. I kept making a joke that somebody needs to save the puppets, “Operation Save the Puppets.”

KK: What’s the significance of the puppets in the culture?

ST: Karagöz is a Turkish word. It’s the name of the main character in an art form that has stock characters and plays. These performances were bawdy, satirical and funny, and used to speak truth to power. They were rabble-rousers. They were saying the things that otherwise couldn’t be said but couching it in humor and satire to get around censorship in the Ottoman Empire. Sometimes they (puppeteers) would push too far and be arrested.

KK: Why did you decide it was time for you to save the puppets in 2019?

ST: I was on a 10-day meditation retreat in Finland and really downloaded the idea of hakawati and ruminating on my great-great-grandfather and survival. My ancestors were not able to speak. What happened to them? To this day, we still see the repercussions and denialism (of the Armenian genocide. In 2021, despite opposition from Turkey, President Joe Biden became the first U.S. president to recognize the mass killings and forced deportations of ethnic minority Armenians from the Ottoman Empire as genocide.)

How does that impact the psyche of a country to be traumatized and then have the trauma denied? You’re trying to fight for recognition before you can even get to the part where you’re healing those wounds. It’s important for people to be able to tell their own story. How do we speak the truth in a way that people will receive it?

(At the same time) I came across a BBC article on Syria’s last shadow puppeteer and how Syria was working to get UNESCO distinction of Karagöz as part of Syrian cultural and heritage. I thought, “I’ve got to meet this guy.” I got in touch with some colleagues that had worked with UNESCO in Armenia, and they connected me to (people in) Syria. I mentioned that my great-great-grandfather did this too, and we may have a few puppets in his house. And I was on my way to Syria for the first time since the war.

Sona Tatoyan in Syria in 2019, when she discovered more than 180 Karagöz shadow puppets in the attic of her abandoned ancestral home. Photo by Antoine Makdis

KK: What was it like going back?

ST: There were no flights into Syria. I flew from Berlin to Beirut, and a driver picked us up. It was about an eight-hour drive (to Aleppo). Usually it takes four-and-a-half hours, but this was wartime. It was harrowing — bribing people left and right at the checkpoints. Americans were persona non grata, so I was going in on my Armenian passport. That morning, Osman Kavala, a Turkish human rights activist, had been indicted in Turkey on trumped up charges of attempting to overthrow the government. One of my greatest friends and supporters of my work, the man who helped fund my nonprofit, was facing life in prison. It was an intense day. (Kavala remains in prison in Turkey; Tatoyan’s unlikely friendship with him features prominently in “Azad.”)

We finally rolled up to Aleppo, and it was destroyed building after destroyed building — just absolute rubble and devastation. We got to the western part of the city where my family home was, and my uncle was on the balcony waiting for me, which is where the family would always be waiting for us. … I had the experience (growing up) of being peripatetic. I was born in Baltimore, lived in Alabama for a few years, then we moved to Indiana and LA. I came to Wake Forest and then moved to New York City. In Aleppo, that family home was there for five generations.

KK: I’ve read that you hoped to find a few puppets.

ST: It felt like a comedy (routine) where (I pulled out) something else and something else and something else. There were over 180 puppets — house puppets, tree puppets, cows, horses, snakes, a whole world of puppets. There were also sticks, because Karagöz is two-dimensional, and you have a stick, and it moves (the puppet) across a screen and is seen through the screen; and magic tricks. I found a magic box in a war zone. All my life going there, those puppets have been there. They were just hanging out until it was time for us to meet.

KK: Did “Azad” start coming together then?

ST: A week after I found the puppets, I fell down the stairs (breaking a foot). There is a saying in Western Armenian that my father has always said to me, (translated as) “May you break your foot so that you sit at your place, so that you become still.” And that’s what I had to do, because I had been running around too much. On my way out several months later, I met a theatre colleague who knows the power and purpose of Karagöz who told me, “The puppets broke your foot. They wanted you to stay.”

KK: Did you have trouble getting the puppets out of Syria?

ST: Syrian news (media) ended up at the house. There was a lot of talk that the puppets are Syrian cultural heritage (and should remain in Syria). I said, “Wait, these are family objects. My great-great-grandfather was an artist. He’s ethnic Armenian. He was born in the Ottoman Empire, and he performed his shows in Turkish. Then he fled because of the genocide. Syria graciously took him in, and he continued to perform.” I was ripped up about it because I didn’t know if I should take them out. I was in a place that had experienced so much loss already. A friend in Paris said, “Those really belong to the world, and the best thing you can do in terms of sharing the culture and what’s happening in Syria is to get them out. God forbid, another thing happens, and they get destroyed.” I packed them up — they’re flat objects — in a small carry-on suitcase and took them out.

KK: What are the puppets telling you?

ST: “It’s time to understand the full spectrum of your inheritance.” All my life, I didn’t want this inheritance. I didn’t want to be a descendant of genocide survivors. I wanted to be American, not (part of) this sad, gruesome thing. The discovery of the puppets was a deep epiphany that I have that inheritance of trauma, but I also have an inheritance of storytelling.

KK: What is the message of “Azad”?

ST: The show in many ways is about the power of paradox. We live in a world that tries to be definitive; it’s good or it’s evil. I think that the more we can begin to inhabit nuance and understanding of the full spectrum of life, the freer we become. The thing that you thought was what broke you is actually the thing that helped make you. It’s this circular understanding … to embrace the totality of life and always question and not be so certain because things are always shifting and changing. That gives you the opportunity to discover more as opposed to shutting down. That’s the cornerstone of a great education and becoming caring, compassionate and powerful citizens in the world to question, to understand, to put ourselves in the shoes of another.

KK: When we first met 10 years ago, you talked about how you just wanted to be a normal American kid when you were growing up in Indiana. You’ve said that having Professor Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77) was a turning point in your life, and you mentioned this in “Azad.” How did she impact you?

ST: I had two classes with her, a poetry and performance class and a humanities course, the philosophy of liberation and literature. That (previous) summer I read all her books, which I was feeling a lot of affinity with as a woman and being kind of from another community in America.

In the midst of reading her books, I came across “Black Dog of Fate” by an Armenian-American writer named Peter Balakian. I was astonished to see it at the time. There’s someone else who had my experience. His book is about his experience growing up in (New) Jersey, his grandmother surviving (the Armenian genocide) and the geopolitical issues around how every U.S. president would say, “We’re going to acknowledge the Armenian genocide.” And that time would never come. I became incensed, and it was like a lightbulb went off.

On the first day of her (Angelou’s) humanities course, I went up to her after class, and I started crying. I told her, “I was reading your books, and I came across this other book, and I’m Armenian, and this and that.” She put her hand on my shoulder and said, “Miss Tatoyan,” — she always called everyone by their last name — “when something is the truth, you must speak it.” I will never forget that moment.

That semester I was doing a play that Sharon Andrews was directing called “Mad Forest,” which was about the Romanian revolution in 1989 and the overthrow of Nicolae Ceaușescu. It perfectly aligned with (Angelou’s) course. She (Angelou) came to the play and bought tickets for the whole class and several of her friends. … I remember getting off stage and saying, “This is what I’m doing with my life. This is what storytelling, that alive, communal, healing space is like.”

Tatoyan’s weeklong stay as artist-in-residence was sponsored by the Provost’s Office, Wake the Arts, the Interdisciplinary Arts Center, the Department of Theatre & Dance and the Program for Leadership and Character.

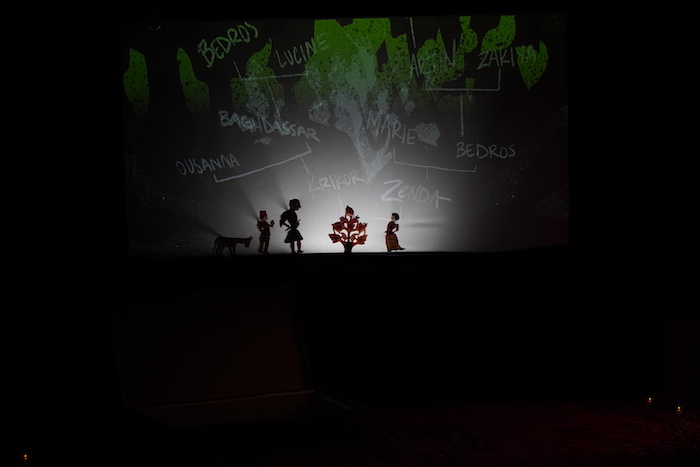

Sona Tatoyan's family tree is displayed on a screen during "Azad."