Editor’s note: Memorial Day honors the men and women who died while serving in the U.S. military. In 2022, a year after the conclusion of the Afghanistan War, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III said service in that war “demanded significant and selfless sacrifice. Many (s)ervice members still bear the wounds of war, to body and to soul, and 2,461 brave heroes never made it home.”

Capt. Connor Murphy (’18), a logistician in the U.S. Army Reserve, shared with us an account of his interview with Ethan Groce (’13), a veteran Army interpreter onsite during the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 who is committed to remembering the valor of fallen service members.

— Maria Henson (’82)

Ethan Groce (‘13) was stationed outside the South Gate at Hamid Karzai International Airport for the final days of the United States’ presence in Afghanistan. Photo above courtesy of U.S. Army. Other photos courtesy of Groce unless noted.

***

Ethan Groce (’13) grew up in a small town outside of St. Louis, Missouri, with an interest in different cultures.

“A liberal arts school was in my blood before applying for college,” he said. Wake Forest was a natural fit. It rekindled a childhood desire to serve — this time to serve his country.

“I knew I wanted to do something related to military intel,” he said, with its application of interpersonal skills.

After basic training, Groce went to Fort Huachuca in Arizona for training as a unit intelligence collector and later attended the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center in Monterey, California, to learn Persian Farsi and Dari.

He was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Liberty in North Carolina. Within a year, there were already whispers that the division would assist with the American withdrawal from Afghanistan as the U.S. occupation ended.

U.S. officials negotiated withdrawal conditions with the Taliban, who had been accused of sheltering the architects of the 9/11 attacks. The deal stipulated that U.S. forces had until Aug. 31, 2021, to remove American equipment and personnel, including Afghans who supported the United States, or risk their capture.

Groce and two fellow interpreters at the South Gate of Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) in Kabul, Afghanistan

The Taliban began sweeping across Afghanistan before the deadline, turning Kabul, the capital city, into a bottleneck for evacuation. The swift takeover created an urgent crisis: more than 100,000 Afghan nationals with Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) status needed evacuation.

With the Taliban arriving in Kabul on Aug. 15, 2021, U.S. forces had only 15 days to evacuate Afghan refugees. It would prove impossible to evacuate them all, and those who remained would become targets.

Groce was quickly tapped to help. “My platoon sergeant told me my name was on a deployment list,” he said. “I was one of six people plucked for language skills.”

On Aug. 18, 2021, Groce flew to Kabul. The rush to get interpreters into Afghanistan was so sudden that service members arrived at what was then called Hamid Karzai International Airport with their personal cellphones. Once there, Groce and his fellow interpreters were attached to infantry units at the airport, working to get refugees out of Afghanistan.

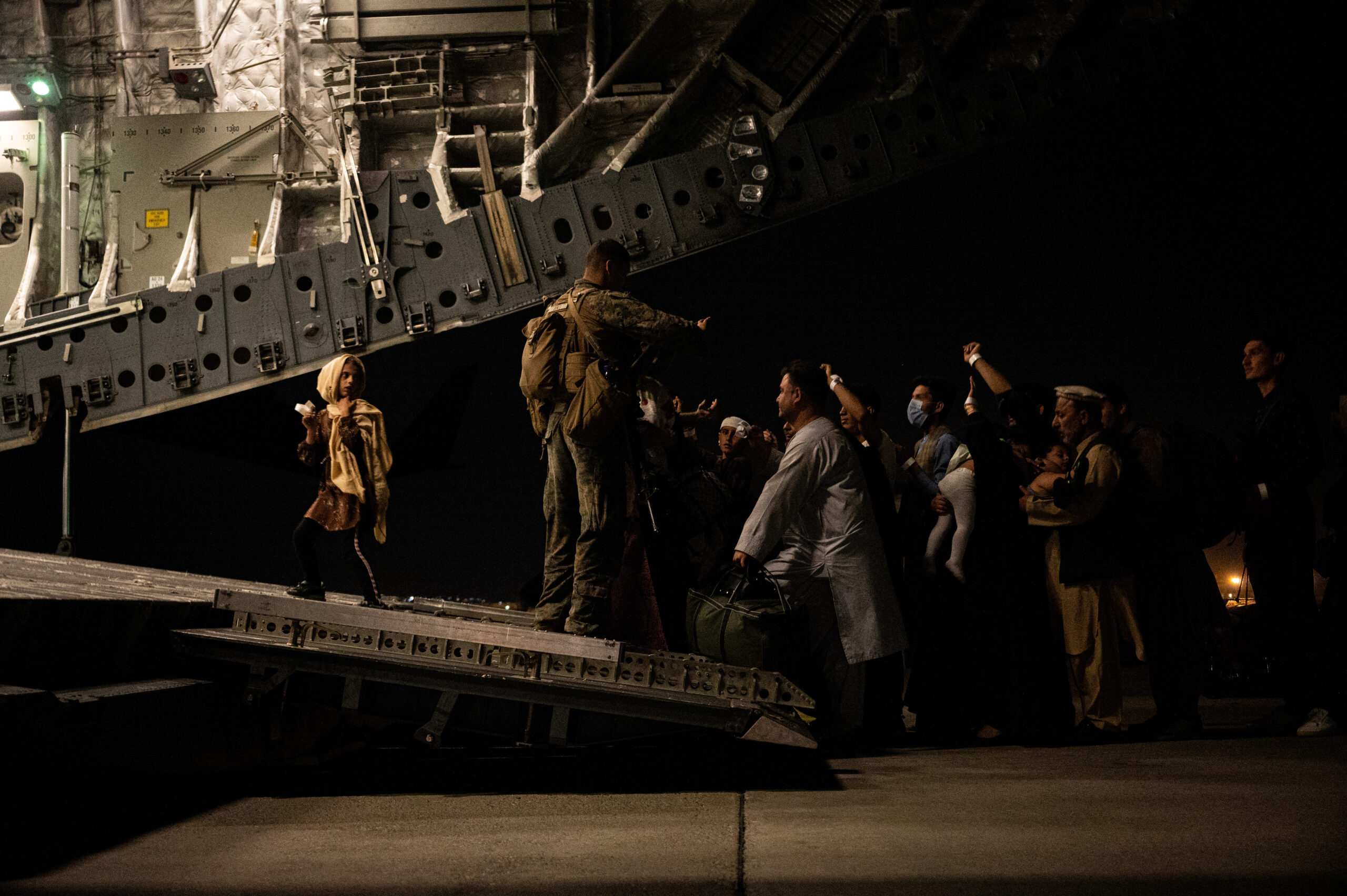

A child walks up a ramp during the airlift from Kabul in 2021. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Air Force

“We would speak with the Taliban directly, with our commanding officer behind us telling us what to translate,” Groce said. “Never in my life did I think I’d be speaking to Taliban members on behalf of the United States.”

The clock was ticking toward the Aug. 30 deadline to get refugees out.

“We had a list from the State Department of people we wanted to get out. We’d explain to the Taliban why we needed people through the gate,” said Groce. “The Taliban would come back with their own requests. They were just time-taking maneuvers because they knew our deadline. If we stayed longer, all hell would break loose.”

Thousands of Afghan nationals waited outside the airport, hoping to escape living under Taliban rule.

In the final days at the airport, Kabul took a dangerous turn. Groce had been working on Aug. 26 at South Gate, the primary gate for civilian entry, when he felt a quaking boom.

“To this day, I can still remember hearing the explosion and noticing how distinct it was from the many other loud noises we would hear on a daily basis,” said Groce. “We didn’t yet know what it was until about 15 seconds afterward.”

Groce in Afghanistan

An attack by a lone suicide bomber of ISIS-K on the nearby Abbey Gate at the airport killed 13 American service members and about 170 Afghan civilians.

“There was a lot of confusion on the ground for several hours,” said Groce. He added that while it may sound odd, it was a relief for him to learn the Taliban wasn’t responsible for the bombing after he had spent so much time mere feet from Taliban representatives.

Regardless, the attack left Groce with a sense of loss. He did not know anyone who died, but he felt a connection that was hard to shake.

“I shared something in common with one of the Marines, Lance Cpl. Jared Schmitz,” Groce told me. “He hailed from Wentzville, Missouri, a town near where my uncle lives and only about 45 minutes from where I grew up. …

“I thought about how Jared and I probably had shared experiences growing up outside of the St. Louis area and may even have joined the military for similar reasons,” he said.

Fallen U.S. Marines honored at a ramp ceremony at Hamid Karzai International Airport. Photo courtesy of U.S. Central Command Public Affairs via Wikimedia Commons

Groce wondered aloud to me if he ever had walked past Schmitz back home without knowing it. “When I read Jared’s obituary, I felt like I shared (a) moment with him.”

The Abbey Gate attack was the single-largest casualty event for U.S. forces in Afghanistan in a decade. With days remaining before U.S. forces departed, the attack iced refugee arrangements that Groce and his fellow service members had negotiated.

While President Joe Biden called the August 2021 operation one of the biggest airlifts in history, with more than 120,000 people evacuated to safety, there are no official estimates for the number of Afghans with Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) status who remain under Taliban rule. (Afghans could apply for the status by meeting various requirements, including facing an ongoing threat for having worked by or on behalf of the U.S. government for at least a year in Afghanistan.) U.S. State Department officials believe a majority of those eligible for SIV status were left behind.

“Two more minutes, and we would have hit the deadline."

Afghan families who escaped have been resettled across the United States and given the opportunity to create a better life in safety. Their escape was made possible by the sacrifices of fallen service members such as Lance Cpl. Schmitz.

As his plane — one of the last carrying American forces — left the tarmac, Groce checked the time. His last minute in Kabul was 23:58 on Aug. 30. “Two more minutes, and we would have hit the deadline,” he said.

Groce, now living in Cottleville, Missouri, left active duty last June, saying his time in Afghanistan was short but that his deployment left an indelible mark on his life. He continues to serve, both in the U.S. Army Reserve and through his work as a social services specialist for the Missouri Department of Social Services.

Capt. Connor Murphy (’18) is a logistician in the U.S. Army Reserve as an assistant operations officer in the 3rd Transportation Brigade, Expeditionary at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. He was commissioned from Wake Forest’s ROTC “No Fear!” Battalion to the 822nd Movement Control Team in Brockton, Massachusetts, where he was unit commander from 2019-2021. On the civilian side, Murphy writes as digital communications director for the advocacy organization Humanity Forward. He lives in the Washington, D.C., area with his wife, Emma, and their many houseplants.