Jump to:

- Jeanne Whitman Bobbitt (’79, MBA ’87)

- Thomas E. Mullen (P ’85, ’88)

- Jenny Robinson Puckett (’71, P ’00)

- Sandra Combs Boyette (MBA ’95)

- Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74, P ’23)

- Marybeth Sutton Wallace (’86)

- Nathan O. Hatch (L.H.D. ’21)

- Margaret “Peggy” Supplee Smith (P ’86)

- Al Hunt (’65, D.Litt. ’91, P ’11)

- Michele Gillespie

- Mary Dalton (’83)

- Debbie Best (’70, MA ’72)

- Barry Maine

- Rogan Kersh (’86)

Jeanne Whitman Bobbitt (’79, MBA ’87)

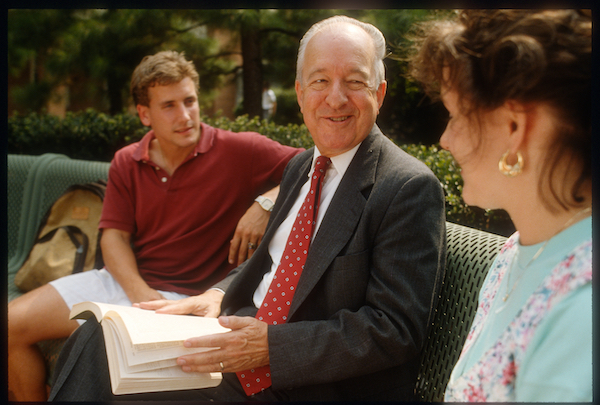

Jeanne Whitman Bobbitt (’79, MBA ’87) worked as Ed Wilson’s assistant for about four years after completing her graduate studies at the University of Virginia. She is vice chair of the University Board of Trustees.

GENERATIONS OF Wake Foresters came to know Ed Wilson — Provost Wilson, as decades of alumni will forever refer to him — not in his administrative roles but as the sonorous voice spinning from memory the opening lines of “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” on a warm April afternoon. In his tiered Tribble Hall classroom, its windows standing open to the scent of early magnolias, we were spellbound. Those times — and all the times he spoke, either his own words or the lines of one of the poets he admired — were mesmerizing.

He was teacher, eulogist, historian of Wake Forest, lover of literature and cinema, and most of all, lover of his family and his North Carolina home. He was also one of the chief strategists of a University built on intelligent and humane principles. His wisdom and values helped propel a small, somewhat underfunded North Carolina institution into the ranks of one of the nation’s most respected universities.

Ed Wilson knew that ideas and people build great institutions, and he sought and attracted both — and built an environment that valued both. He would interview a candidate for an appointment in accountancy, and the two would talk about the career of filmmaker John Huston. With a candidate in French language and literature, the topic might be W.J. Cash’s “The Mind of the South.” A budding law professor might be invited to tell of her relationship with the grandmother who reared her.

Ed Wilson looked for intellect, powers of imagination, character and heart. He sought for our Wake Forest those whose values put students first, community second and personal career third. Profoundly decent, he respected women and men equally and was disgusted by those who were dismissive of the frailties of others.

He reveled in complex and accomplished minds. Ed Wilson brought Germaine Brée (D.Litt. ’69), Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77), James Dodding to campus. He sought people whom he would enjoy around a dinner table at his Timberlake Lane home. Before “personnel” became “human capital” or “talent management,” Ed Wilson treasured people as the center and the engine of the enterprise.

"One of my fondest memories is of sitting on Provost Wilson’s living room floor one evening, after a spaghetti supper delivered from the Pit, and reading Dylan Thomas’s play, Under Milk Wood, aloud with classmates.”

His occasionally maddening habit of procrastination was more often than not a conscious strategy. He once told me that if one has the equanimity and, I would add, strength of mind, to wait out the first waves of response to a problem, better information will likely emerge. Emotions will shift. Solutions will disassemble and re-assemble themselves. And the community will likely become more prepared to accept the solution that shapes itself and is shaped by its leadership. Ed Wilson had a preternatural calm in the face of a crisis and, usually, exquisite timing for the implementation of resolution. Whether that discipline would have thrived in our 24-hour news cycle and the voracious maw of social media we will never know. But that practiced discipline saved the dignity and sometimes the careers of many over the years. Ed Wilson gave people time to come around to the positions that their “best selves” would espouse — because that “best self” was the one he was generous enough to recognize as the “real” self.

Finally, he had the heart of an idealist and the mind of a pragmatist. His instinct was to guard the well-being of the individual, especially those perceiving themselves ranged against the powers of traditional structures. But his pragmatic eye saw that safeguarding the institution could require canny compromise for the greater good. He was not a man to die in ditches. He lifted our eyes to the hilltop and urged us up together — but if the hilltop were unassailable, he had a Plan B in mind. Pyrrhic victories were not his way — nor were one-sided ones. Although he always took the moral high ground, he often found a way to accommodate a variety of interests. His first duty, even when it grieved him to act against the interests of an individual, was the strength and well-being of the institution.

And therein lie the lessons that have stayed with me every bit as strongly as the memory of “The Song of Wandering Aengus” recited, incongruously, by a smallish man in a business suit, hands thrust in pockets, rocking occasionally to the balls of his feet as the wash of language overtakes him and his listeners. Wake Forest awarded me degrees. Ed Wilson prepared me for life. His days were lighted by unexpected moments of whimsy and anchored in his love for his family and his joy in his friends. He was the same man at home, at work, in the classroom. He was, and remains forever, my North Star.

Thomas E. Mullen (P ’85, ’88)

Thomas E. Mullen (P ’85, ’88) succeeded Wilson as dean of the College in 1968 and served until 1995, and he was a history professor from 1957 until 2000.

EDWIN G. WILSON was more like an older brother to me than a “boss,” even though as acting dean of the College in 1958-59 and in his various leadership roles afterward, he was in every way my academic and administrative superior. This relationship continued with me as dean and Ed as provost until 1990, when he retired from the provost’s position. Throughout the years, he was my superior but also my very close friend, one who did not offer his advice but who would always give it when asked.

When Ed married Emily Herring in 1964, it happened that my wife, Ruth, and I were spending the summer in a student apartment in Paris, where we had more room than we needed. So, the honeymooners paid us a most welcome visit, and we four adults, with Renee, our 20-month-old daughter, drove to Chartres to visit the cathedral. Enjoying a picnic on the way, Ruth and I saw Ed without a coat and tie for the first time in seven years. He gave up much of his formality under the influence, I think, of Emily and later their three children. He had always been approachable for colleagues and students but, thanks to family, he became even moreso.

“What will future students find at Wake Forest? What students have always found, I hope: a place which men and women of goodwill everywhere might, if they knew it, be happy to call home.”

As dean and then through his many years as provost, Ed protected and preserved many of the academic and moral values he and others brought with them from the Old Campus in Wake Forest, North Carolina. At the same time, he took advantage of the opportunity to help expand Wake Forest’s library from 95,000 volumes in 1956 to 1 million volumes in 1989. The introduction of honors programs, interdisciplinary and departmental, was achieved through a committee he appointed in 1959-60. Some years later it was he, supported by President James Ralph Scales, who created an art department and sought out its first faculty members.

So far as I recall, he did not name planning committees but engaged in a great deal of planning with the help of other members of the faculty and administration. Much of the planning in the Scales administration took place in the brain of Ed Wilson, who neglected to take credit for himself. In the area of planning and bringing changes to his alma mater, as in so many other ways, Ed devoted all his efforts and talents to making Wake Forest a better undergraduate college and a stronger university. I doubt that anyone in the future, no matter how long Wake Forest lasts, will ever deserve more than he the informal title of “Mr. Wake Forest.” Should, however, a woman be called “Madame Wake Forest,” Ed’s generous spirit would give that step his happy approval.

Jenny Robinson Puckett (’71, P ’00)

Jenny Robinson Puckett (’71, P ’00) is a retired lecturer in Spanish who also taught a first-year seminar called Modern Wake Forest: A Living History. Puckett is the author of books about the University’s history; in 2016 she received the Medallion of Merit, the University’s highest honor.

He was a man; take him for all in all,

I shall not look upon his like again.

HOW WELL Ed Wilson knew those words from “Hamlet.”

Of course, Ed would never ascribe Shakespeare’s princely tribute to himself. Humility was a defining mark of this extraordinary man. In his later years, he always seemed a bit reticent and uncomfortable when people called him “Mr. Wake Forest.” He would smile and nod graciously, but one wondered if he might be imagining someone else he had known, to whom he would gladly bestow such a title.

Ed was much more at ease when others took the center stage. His interest in all people, and their stories, never ebbed. He loved to teach. For him, it was the highest calling. He wanted younger generations to experience an intellectual awakening to the power and beauty of language. He wanted students to understand that great literature belongs to us all, in any age or at any age.

I met Dr. Wilson when I finally secured a spot in his Romantic poets class. Immaturely, I had some initial doubts about the relevance of the subject matter, but everyone said that it was the class to take.

Poetry? Really? I was from the mountains. I already knew how to hike, camp, snow ski and read stacks of books during winter storms or rainy summers. Books of poetry were notably absent from those stacks.

But in the spring of my junior year, Ed’s class amended that viewpoint.

Each day that Ed stood in front of us, he talked to us as if we were his equals. He looked at us, one by one, as he spoke from the heart. We could see Wordsworth’s blazing yellow daffodils on the English hillsides. We could feel the wretchedness of Shelley’s Ozymandias as his statue languished on that lonely stretch of sand: Lo, how the mighty have fallen.

We learned from Ed Wilson that no generation is better or smarter than any previous one. As centuries pass and the world changes, forms of expression will evolve. But the human heart will always want to express the same fears, longings and hopes. We learned that poetry from any age or place can come alive for us if we only pay close attention.

Many years later, when it was my turn to teach at Wake Forest, Ed was my mentor. I often sought his advice on many subjects, which he gladly gave, over lunch or coffee, or in his library office. When he visited my classes, those were great days. I watched as Ed Wilson drew young listeners into a large and comfortable forum of thoughtful learning that was always uniquely his.

Ed was a gentle man, unfailingly kind and welcoming. In his lifetime the world around him changed radically, and sometimes terribly, but nothing could ever shake his kindness nor his optimism that things will probably turn out all right.

Ed Wilson enriched all of our lives with his intellect, affection, guidance and devotion. We, his Wake Forest family, shall remain in his debt for these gifts that we have cherished for so many years — and that cannot be repaid.

We shall not look upon his like again.

Sandra Combs Boyette (MBA ’95)

Sandra Combs Boyette (MBA ’95) was the University’s first female vice president and a recipient, in 2019, of the Medallion of Merit,the University’s highest honor.

KNOWING ED WILSONas colleague and friend was a happy, instructive privilege. Early in my Wake Forest career, I understood why he was regarded with such profound respect. He was welcoming and treated all with kindness and openness.

He instructed me and many others in the language of his beloved alma mater. One example: As a young foundations officer, I found it helpful to have an academic administrator or faculty member accompany me on calls. Having Provost Wilson on a visit with a foundation director was the greatest asset imaginable. He articulated, eloquently, Wake Forest’s history and place in higher education. His phrases informed my own vocabulary about the University. His presence, too — that rich baritone voice, his friendly poise and his academic gravitas — made his message memorable.

I was fortunate to share an office suite with Ed Wilson for my last seven years of service. Interacting with him on a daily basis was delightful.

I was fortunate to share an office suite with Ed Wilson for my last seven years of service. Interacting with him on a daily basis was delightful.

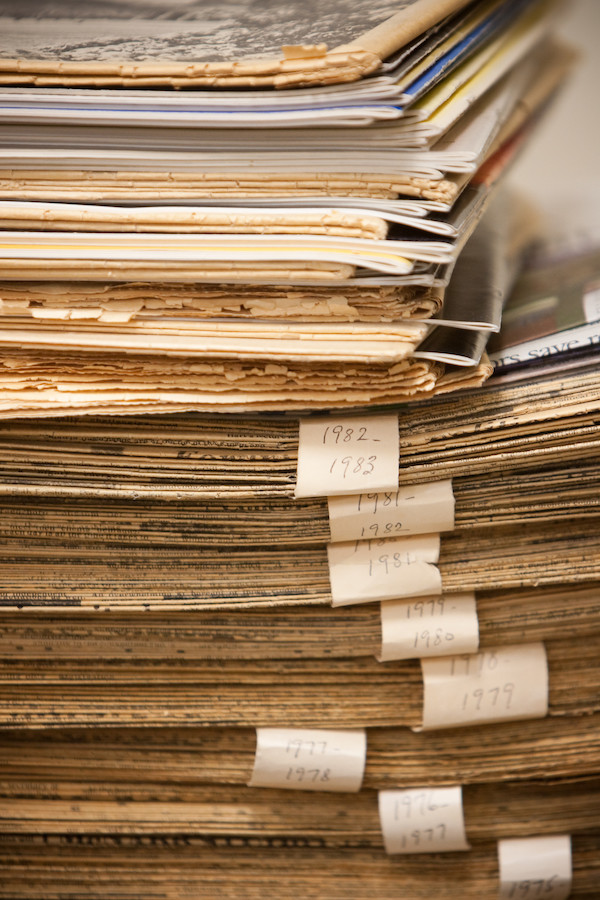

Conducting research for the fifth volume of Wake Forest’s history, he read every issue of the Old Gold & Black and every Howler from the James Ralph Scales years. Occasionally, he would emerge from his office and ask, “I recognize everyone in this picture except this one. Do you know who it is?” If I could identify the student, he would always exclaim, “Of course!” and instantly recount an anecdote about that person as an undergraduate.

Once, I mentioned a medical lecture I had attended in which the speaker advocated coffee as perhaps the best antioxidant in the American diet. Thereafter, around 3 p.m., Ed would say, “I’m going to Starbucks for my antioxidant. May I bring you one?”

And on the morning after the election of a presidential candidate whom we both supported, he arrived at the office, stood in front of my desk and sang “Happy Days Are Here Again.”

May all of us who learned so much from Edwin Graves Wilson honor and emulate his powerful example of a life wonderfully lived.

“Wake Forest has been the center of my life. Asking what I think about Wake Forest is like asking me what I think of my family.” — Ed Wilson<br />

Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74, P ’23)

Professor Emeritus of Biology Herman Eure (Ph.D.’74, P ’23) was the University’s first Black graduate student on the Reynolda campus, the first Black graduate student to earn a doctorate and the first full-time Black faculty member. He has been a University trustee and, in 2017, received the Medallion of Merit, the University’s highest honor.

MY FIRST real encounter with Ed Wilson was in spring 1974. I met with both Ed and then-Dean of the College Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88) for my job interview. My first impression was that Ed was a gentle, thoughtful man who had a clear sense of what he wanted in a faculty member and that he was committed to changing the faculty’s ethnic makeup. His questions were direct, thought-provoking and showed a genuine interest in who I was and what I could bring to Wake Forest. I decided to accept the University’s job offer in fall 1974.

I didn’t have many interactions with Ed again until 1976. The Black faculty wanted to create an office on campus to address the needs of Black students, who felt they were not being heard by the administration about biased treatment from some faculty and students. I worked almost exclusively with Ed, explaining why I felt the office was necessary to address these concerns and how it might affect students if they saw that Wake Forest was interested in their welfare by creating an office.

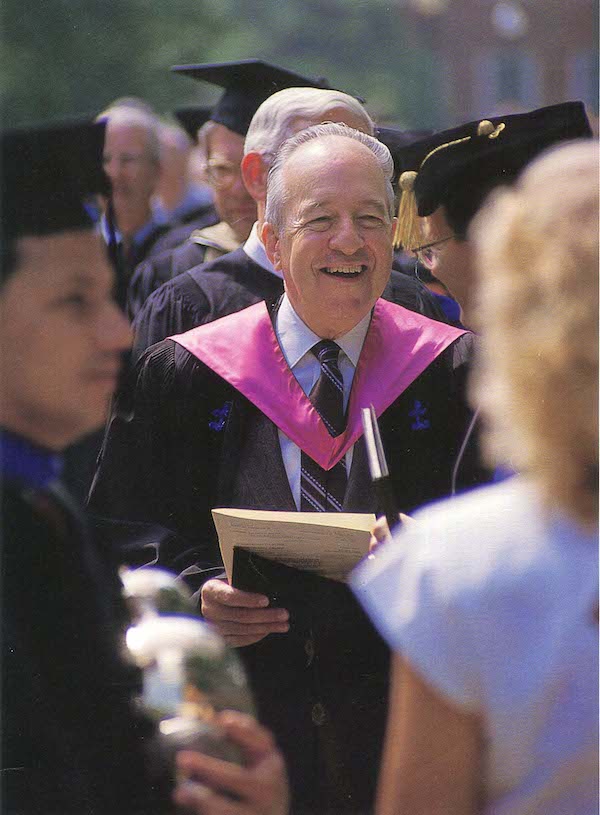

Wake Forest friends arrive to wish Ed Wilson a happy 100th birthday at the Wilsons’ home in the Faculty Drive neighborhood.

To make a long story short, Ed — I am sure with the blessings of President James Ralph Scales, himself a minority as a member of the Cherokee Nation — in 1977 created the Office of Minority Affairs. The office hired Larry Palmer as its first director. He served three years. At that time, Wake Forest was changing administrations, and my thought, along with that of the three other Black faculty members on campus, was that without a director, the office might be deemed unnecessary. Ed asked me if I would direct the office and continue as a biology professor. I agreed.

We worked together to make the office an integral part of the University’s administrative structure, and its creation and success owe a lot to Ed Wilson. That office changed how we taught, what we taught and whom we hired as faculty.

“When I think of Dr. Wilson, I think of Chaucer’s line ‘And gladly would he learn, and gladly teach.’ Thank you for showing us all the way.”

My relationship with Ed grew as I advised him on many issues dealing with race and gender, laying the foundation for a decades-long professional and personal relationship. I cherish that time. Ed had a commitment to fairness and equity that set him apart. He was the embodiment of what is good and right about Wake Forest. His genuine interest in making the University a more diverse place with respect to race, gender and socioeconomic equity owes a lot to his willingness to see a much different Wake Forest than the one he attended. He was the personification of our motto, and all of us who worked with him are richer because of that association.

Marybeth Sutton Wallace (’86)

Marybeth Sutton Wallace (’86) coordinates the Wake Forest Fellows program. She first met Ed Wilson in 1982 as a freshman in DeTamble Auditorium after a College Union film showing and took his classes as an English major in 1985 and 1986. After graduate school, she returned to work for him as assistant to the provost in the late 1980s.

I ONCE TRIED to explain to a friend why students never wanted to miss one of Professor Ed Wilson’s classes; why it was that at 2:45 p.m. on a Friday afternoon, a classroom in Tribble, 216-C, was filled from front to back with students thoroughly enchanted, and except for one deep resonant voice reading “The Song of Wandering Aengus” or “Kubla Khan,” not a sound or shuffle could be heard.

“You could have been on your way to the beach — or the mountains,” my friend exclaimed, “or throwing a Frisbee on the Quad.”

But how could the beach or mountains compare with the dizzying lake country of Wordsworth’s boyhood, the lush green of Yeats’ Sligo or the romance of Byron’s Italy, Greece and Spain?

“You just couldn’t skip Dr. Wilson’s class,” I protested, “because you couldn’t bear to disappoint him.” And you couldn’t bear to disappoint yourself, either. “Young and easy under the apple boughs,” we had that feeling that what we were learning was nourishing our souls and fortifying us for the years to come.

We left his classroom believing we could be better people. We left his classroom believing we could do something to make the world more beautiful. And we were merely one generation of students that Dr. Wilson touched in a teaching career that spanned more than a half-century.

When I was teaching high school English in Raleigh, a fellow teacher at Enloe, Sally Rigsbee Humble (’61, P ’91), recalled that same feeling of being swept away by Dr. Wilson’s classes. As she prepared her own lesson on Keats’ “The Eve of St. Agnes,” she remembered Dr. Wilson’s riveting lecture, the brilliant imagery, the rich language, pages of notes. When she gleefully retrieved the dusty notebook from the attic, eager to impart this wealth of knowledge to her students, she was stunned to find one sentence under “The Eve of St. Agnes.” Spellbound, she had written simply, “Dr. Wilson read the poem.”

One of the first things Dr. Wilson would do in the course of a semester was to invite each of his students by his office — just to talk — about hometowns (he loved the names of hometowns), families, favorite books, recent movies, plays — on Broadway or at the Stevens Center — perhaps even ACC basketball or Eastern North Carolina barbecue.

Though his life was anchored at Wake Forest, Dr. Wilson’s life’s work has extended to every town across this state, every corner of the country and beyond as his students everywhere, with the force of Shelley’s West Wind, carry forward that torch for the humanities, that acknowledgment that we are more alike than we are different.

He showed us that in the most difficult times in our lives, “all hatred driven hence, the soul recovers radical innocence… ” and that we can, “though every face should scowl and every windy quarter howl, or every bellows burst, be happy still.”

Nathan O. Hatch (L.H.D. ’21)

President Emeritus Nathan O. Hatch (L.H.D. ’21) was the University’s president from 2005-2021. He received the Medallion of Merit, the University’s highest award, in 2022.

ED WILSON REGULARLY described Wake Forest as a place of hospitality, a community in which anyone of goodwill could find acceptance, affirmation and intellectual engagement. My wife, Julie, and I felt that kind of embrace from Ed, and many others, when we came to Wake Forest, and I will always believe that quality lies at the heart of a Wake Forest education.

Ed took people seriously. His brilliance as scholar and teacher was coupled to a deep understanding of his colleagues and his students. He embraced them, took interest in them and longed that the community of learning at Wake Forest would serve, in the words of John Henry Newman, as “an Alma Mater, knowing her children one by one, not a foundry, or a mint, or a treadmill.” Ed embodied the conviction that intellectual rigor should be linked to deep personal relationships.

He knew how to see people deeply and make them feel seen.

Ed Wilson with Julie Hatch. Photo/Lauren Martinez Olinger ('13), Red Cardinal Studio

Ed’s presence — his teaching, his mentoring, his leading and his words — worked to define the essence of Wake Forest for generations of students. Ed worked hard at the task of widening the University’s embrace to include many who had been previously excluded. For him, hospitality was never sentimental, just hanging out with friends. It meant extending welcome to those who, for whatever reason, may have felt like strangers.

In the current age, which knows a scourge of loneliness and of smash-mouth partisanship, Ed Wilson has a powerful legacy. It reminds us to know each other deeply, to build strong friendships, to engage those with whom we disagree and to go the second mile to make Wake Forest a place of deep human connection for everyone.

“No one other than my parents made a greater impact on my life. He was a teacher, a mentor, a friend. I’m going to miss him terribly.”

Margaret “Peggy” Supplee Smith (P ’86)

Harold W. Tribble Professor Emerita of Art Margaret “Peggy” Supplee Smith (P ’86) arrived at Wake Forest in 1979 and taught art and architectural history, served four terms as art department chair and helped establish the women’s studies program (now the women’s, gender and sexuality studies department). She received the University’s Medallion of Merit in 2014.

I FIRST MET Ed Wilson when I interviewed for a job in Wake Forest’s art department in 1979. In those days, candidates met with Provost Wilson and Dean Mullen as part of the interview process. They were Wake Forest’s secret weapons. Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88) was charming and wry; Ed Wilson was gracious and erudite. Both men, clearly smart, imbued civility.

Ed recently had secured grants from the Mellon and Rockefeller foundations to develop a visual arts program commensurate with the new Fine Arts Center. He was committed to bringing the arts to Wake Forest — along with more mid-level faculty women. Educated in the Leaksville, North Carolina, public schools (and then Wake Forest College and Harvard University), Ed had a deep knowledge of history and literature. He embraced the arts with the enthusiasm and openness with which he approached life. Ed regularly attended concerts, plays, lectures, poetry readings and gallery openings, a practice he continued after his retirement.

Through the years, I realized that Ed’s philosophy was “yes,” which was great when his colleagues approached him with a project or proposal. He was inevitably curious and amazingly nonjudgmental. He liked British Romantic poetry and Vanity Fair magazine. He liked “Casablanca” and “Brokeback Mountain.” He liked the Winston-Salem Symphony and Bob Dylan.

Ed genuinely liked people, and they liked him. People approached him, saying, “Remember me?” At basketball games, everyone walking up and down the steps stopped to say hello. Ed was a fervent Deacon fan, and his induction into the Wake Forest Sports Hall of Fame delighted him since he was famously unathletic.

He had a sense of humor, which those who attended President Thomas K. Hearn Jr.’s inauguration in 1983 will remember. When President Emeritus James Ralph Scales forgot to introduce Governor James B. Hunt (LL.D. ’82, P ’88, ’90), to the consternation of the audience, Ed sprung to the microphone to rectify the oversight, adding that, yes, this was the job of a provost.

“Dr. Wilson’s ‘Essence of Wake Forest’ was the inspiration for my Senior Oration back in 2018. No one has “loved what Wake Forest stood for” — or shaped what that phrase could mean — more than Dr. Wilson. It was an honor to know him. Rest in peace, Mr. Wake Forest.”

Al Hunt (’65, D.Litt. ’91, P ’11)

Al Hunt (’65, D.Litt. ’91, P ’11) writes a weekly column on Substack and is a co-host of the “Politics War Room” podcast. He is the former executive editor of Bloomberg News and previously served as reporter, bureau chief and Washington editor for The Wall Street Journal. For almost a quarter century he wrote a column on politics for The Wall Street Journal, then later for the International New York Times and Bloomberg View. He is a Life Trustee on the University Board of Trustees.

WAKE FOREST has been blessed with great leaders, distinguished scholars, superb students and world-class athletes.

In a 190-year history, however, there has been only one Mr. Wake Forest: Edwin Graves Wilson, revered teacher of English literature and poetry, dean of the College, University provost, the school’s athletic representative.

Ed Wilson was so much more.

Arriving on the old Wake Forest campus, a place he always called “the holy land,” as a 16-year-old freshman in 1939, he stayed, except for several years in the U.S. Navy during World War II — he served during the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa — and then getting a Ph.D. at Harvard.

An extraordinary nearly 80 years, a gift to all those touched by him right up until he passed away at 101 in March.

I’ve never known a kinder, more caring person. I’ve never known anyone with more intellectual breadth and genuine strength. There’s an old observation that “nothing is so strong as gentleness and nothing is so gentle as real strength.” That’s Ed Wilson.

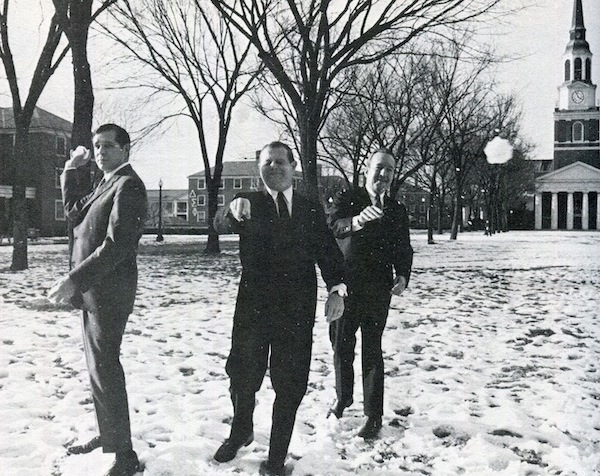

President James Ralph Scales; Gene Lucas, vice president for business and finance; and Ed Wilson in 1970

He could be remarkably prescient.

He was on the dean’s committee that kicked me out of Wake Forest for throwing a wild party. (It was so tame by today’s standards that my kids want to know what really happened.) During this hiatus I went to work as a copy boy for a Philadelphia newspaper and fell in love with journalism, returning to college in September.

A couple of days later, I ran into Dr. Wilson in Reynolda Hall. He wanted to hear all about my experience and to make sure I would write for the Old Gold & Black. He knew what I didn’t: that suspension could be the jolt my carefree life needed.

The next year was a seminal change in his life. He married Emily Herring (MA ’62, P ’91, ’93), also a professor and writer. For 59 years she has brought a zest to the Wilson home with three marvelous children and four grandchildren.

Emily Herring Wilson

Mr. Wake Forest loved literature, theatre, movies, ice cream and Wake Forest students to whom he always was accessible.

On campus, casual attire was a jacket and tie. Once I invited him to Washington’s Gridiron dinner, a white-tie gathering of the political and journalism elite. No one looked more distinguished that evening than Ed Wilson.

He conversed comfortably with prominent political figures. He also had engaging conversations with two of my close friends: Dick Flavin, a Boston television anchor and political satirist, and Steve Sabol, president of professional football’s legendary NFL Films.

The man had range.

Whenever I came back to Wake Forest in recent years, I tried to see Ed. (It always was hard not to call him Dr. Wilson.) He was a big fan of my wife, Judy Woodruff (LL.D. ’95, P ’11), who anchored the PBS NewsHour. She always wanted to make sure a visit with Ed and Emily was on the agenda. He wanted to talk about the NewsHour; Judy just wanted to listen to him.

I keep three books on my nightstand: one I’m reading, another I want to read but am procrastinating and Ed Wilson’s “Songs of Wake Forest,” more than 50 tributes to colleagues; they’re beautifully crafted and tell the story of our modern history. What a treasure he was.

Michele Gillespie

University Provost Michele Gillespie serves as Wake Forest’s chief academic officer. She is the Presidential Endowed Professor of Southern History and from 2015 to 2022 was dean of the undergraduate college. She arrived at Wake Forest in 1999.

WE MET DURING my on-campus interview in his Z. Smith Reynolds Library office. I was nervous about meeting this preeminent teacher-scholar-administrator, who had helped transform Wake Forest into a renowned national university. But he was so warm and witty, and our exchange about our favorite historians and writers was so much fun, that I almost forgot why we were there. What I experienced that afternoon was by no means unique. Ed Wilson made everyone he ever met feel welcomed, and he invited everyone he ever met to engage with him in what it means to be human.

Since that interview a quarter of a century ago, we have talked about books, plays, poetry and all things Wake Forest. We have shared a special affection for Professor Emeritus of History James Barefield. We served together on the search committee that brought us Nathan Hatch (L.H.D. ’21) to become president. I walked beside him when he toured the World War II monument in Washington, D.C., for the first time, and he teared up at the memories of the men lost in the Pacific theater. I have been at readings, celebrations, performances and lectures with Ed. I have attended too many brilliant eulogies that he has given in honor of so many wonderful Wake Foresters. My children have trick-or-treated at his house and sat mesmerized at his knee during his readings of Frost and Yeats. Some of my happiest, most meaningful memories are of special times spent with Ed, and I know I am one of thousands of Wake Foresters who have had similar experiences and feel exactly the same way.

As sad as I am at his passing, I am so grateful to Ed for all that he has bequeathed each of us and Wake Forest. He loved Wake Forest because it spoke to the values he believed in most deeply: friendship, honesty, integrity, beauty and justice. He never wanted us to forget that the humanities and arts are our core, our moral compass, our differentiator, and when aligned with our outstanding graduate and professional schools and powerhouse STEM and social science programs, can move mountains.

I have learned so much from Ed. I hope I can help pass on that learning to the next generation of Wake Foresters. For me, Ed’s legacy is about the transformative power of friendship and the transformative power of education, in its broadest, humanist sense, on behalf of Pro Humanitate.

Papers in Ed Wilson’s office from the research for Wilson’s WFU history book

Mary Dalton (’83)

Mary Dalton (’83) is professor of communication and film and media studies.

IF WE CONSIDER what is best about the essence of Wake Forest, surely Edwin Graves Wilson reflected those values in his unflappable integrity, his commitment to friendliness and honor and his quiet belief in the enduring value of learning for its own sake.

Our friendship did not develop in the usual way. I never had a class with Ed or worked with him on a Wake Forest project until after I became friends with his wife, Emily. This gave me the opportunity to meet him not as Dr. Wilson or Dean Wilson or Provost Wilson or even as “Mr. Wake Forest.”

For me, he has always been Ed.

Seeing him at his home as well as in the public spaces of our campus, I was always struck by how Ed presented the same genuine persona to the people he encountered in all of those spaces. Yes, he brought friendliness and honor but also insight and wisdom.

Our friendship solidified over our shared love of the movies. I continue to marvel at his recollection of films he had seen over the years, starting from the time he was a boy in rural North Carolina, and continuing throughout his life, a period that covers a significant chunk of film history.

At regular Unbroken Circle gatherings of Wake Foresters who enjoyed potlucks and old-time music, Wilson read a few poems for the occasions.

In 2016, I invited him to my introductory film class to talk about his favorite film, “Casablanca,” before the students saw it, and the following year recorded a talk with him about that movie for my students taking the same course in Copenhagen.

What a gift he had for connecting with people of all ages and how very generous he was with sharing that gift.

Ed, like me, enjoyed seeing all types of films. Periodically, we would sit down together and compare notes, and at Christmas he grew into the habit of selecting a book for me, most often a volume on some aspect of our shared passion for film.

Once Ed told me that if he were a student today, he would probably study film. Why not? Movies and, increasingly, television in its second golden age, are powerful engines of cultural transmission that tell us about our place in the world and what it means to be human, sometimes in an indelible currency.

In the later years of our friendship, Ed grew particularly fond of pound cakes I made from my grandmother’s recipe. I started making them for Wilson family events after his oldest grandchild developed a severe peanut allergy. Emily trusted me to provide something sweet that would be safe for everyone to eat.

Ed once said to me, “I’m always happy to see you coming, Mary, but doubly so when you are carrying a pound cake.” I will never again make a pound cake without thinking of Ed, and I will never think of my friend Ed without smiling and feeling happy inside.

“Wake Forest and the world just lost a truly beautiful soul.”

Debbie Best (’70, MA ’72)

William L. Poteat Professor of Psychology Debbie Best (’70, MA ’72) retired last year after 51 years on the faculty and with the distinction of having been the first female dean of the College.

Photo/Lyndsie Schlink

MY EARLY MEMORIES of Ed Wilson begin when I was an undergraduate, then a graduate student and a young faculty member. Across my 57 years at Wake Forest, Ed was a role model, teaching me how to be a faculty member, leader and administrator. Bob Beck, Ed’s back-door neighbor, was my departmental mentor, and on many occasions, the two of us would go to Ed, particularly when serious difficulties arose. Ed’s calming voice, insightful problem-solving and kind support showed me how to be a good listener and to care for others and their problems.

During the Heritage and Promise capital campaign, Ed and I were on the campaign trail together, and I always hated following his eloquent speeches and melodic voice. When I became the first woman dean of the College, Emily gave me a lovely luncheon with women faculty friends, and Ed became my most ardent supporter and secret adviser. One day, when I was dean, I had a group of women students swoon as they told me about a wonderful faculty member whom they could “listen to all day” — Dr. Wilson. When I relayed their praise to Ed, he gave me that familiar bashful smile we’ve all seen.

Over the years, Ed and I did many things together, but perhaps the hardest was speaking at our dear friend Bob Beck’s memorial service. In all that Ed did, it was obvious that he cared so deeply for his friends and family.

As he became less able to visit campus and attend events, I visited Ed and Emily at their home, learning about what their grown-up kids were doing, what Ed and Emily had been reading and whom they had heard from recently. Ed often wanted to talk about the Wake Forest things we loved to do — how we loved our students, teaching them, watching the wheels turn — what I called their “aha” moments. Several times, Ed recounted a magical story — when he first saw and then fell in love with Emily, his lifelong heart’s delight. I was never permitted to leave these visits without giving Ed a goodbye kiss on the cheek! I will miss those wonderful kisses and the man we all loved.

“I will always remember when a student came in late to class and said ‘better late than never’ and Dr. Wilson told him ‘but better never late’. He will be missed.”

Barry Maine

Professor of English Barry Maine has taught American fiction and literature and film.

ANYONE WHO HAS read Ed Wilson’s book, “Songs of Wake Forest,” must admire Ed’s remarkable gift for recognizing the best in people. He could only have developed this gift by taking an interest in people, especially people of Wake Forest. I feel blessed that he took an interest in me. I came to Wake Forest as an assistant professor of English in fall 1981. When, as provost, he interviewed me, he asked me what I wanted to teach, and I replied it was William Faulkner’s novels that most captured my interest at that time. He asked me several questions about “Absalom, Absalom!” I was surprised and delighted to talk with him about my literary interests. I soon learned that Professor Wilson was the most sought-after professor in our department, filling all 63 seats of Tribble Hall C-216 for his lecture courses every semester. Students were mesmerized by his learning and love of poetry.

Over the years, we found another basis for friendship in our love of cinema. My friend Doug Bland (’73, MAEd ’76) and I would often take Ed to the movies. He would see anything, from sci-fi blockbusters to art house films. We sometimes made up the entire audience at the a/perture cinema downtown. Doug and I soon developed a foolproof way of reviewing the quality of films we watched. If Ed looked at his watch during the screening, we knew it was a flop! In more recent years he had trouble getting himself out of movie seats without our help, but he loved to go regardless.

Edwin G. Wilson loved Wake Forest, from the moment he arrived as a student at the Old Campus, to his final days at home. His contributions to this institution of higher learning cannot be tallied. No one has given so much. But Wake Forest also gave something to Ed Wilson. If I may borrow a metaphor from a cinematic classic, Wake Forest was his “Field of Dreams.” It provided him with something commensurate with his capacity for dreaming of an institution that he and other campus leaders and faculty could shape to his vision of what a university should be. And we are all grateful for the place they have bequeathed us.

Rogan Kersh (’86)

Distinguished University Professor of Politics & International Affairs Rogan Kersh (’86) was Wake Forest’s provost from 2012 to 2022.

MY MOST MEMORABLE moment as a Wake Forest undergraduate came outside a classroom — literally just outside, in a Tribble hallway. Several of us seniors gathered secretly during the final session of Blake, Yeats and Thomas to hear Dr. Wilson recite Dylan Thomas’ “Fern Hill.” Most of us had already taken Dr. Wilson’s legendary course, yet our departure from this singular place was not complete without that benediction and farewell.

My Wake Forest education, interrupted by a quarter century, continued when Dr. Wilson generously indulged a rookie provost in hours of conversation. We met at Emily and Ed’s welcoming Timberlake Lane home or Ed’s office in the (ahem) Wilson Wing of Z. Smith Reynolds Library. We walked the Reynolda campus and the original campus, where I can give a passable Ed Wilson tour, including all boardinghouses he inhabited as an undergraduate. Here are two of many lessons Dr. Wilson conveyed.

On our first walk, three weeks into the job, I nervously recited for a patient Dr. Wilson the heap of challenges I sought to swiftly “solve.” Eventually we had wandered most of campus and were standing in the lee of Wait Chapel. “I often found it helpful,” he mused, “to allow some matters to mature on my desk.” Do no administrative harm; avoid action for action’s sake; focus on one or two priorities at a time: these vital lessons were all there in that gnomic Wilsonian utterance.

Soon again I was carrying on to Ed, this time about the University budget — a fiendishly complex machine, replete with amortizations and accrued liabilities, all magically kept aloft by Hof Milam (’76, MBA ’91, P ’00, ’04), then executive vice president and chief financial officer, and a heroic team of budgeteers. Dr. Wilson smiled and reached into his shirt pocket. Displaying an index card with a few lines of figures — had he anticipated my queries? Did he carry it daily still? — he said, “I always kept the budget here, referring to it as needed.” Again, message absorbed: simplify, while never losing sight of the greater whole.

Two among dozens of invaluable pointers about fulfilling a sacred trust: supporting students’ learning and development and faculty members’ research and artistic creations. All who are dedicated to serving that trust owe an indelible debt to Ed Wilson, who did more than anyone to shape a Wake Forest culture of service to education, discovery and the intentional difference-making we term Pro Humanitate.

Dr. Wilson’s own service to Wake Forest outshines the brightest diamond. As a young faculty member, he helped persuade colleagues — including his former professors — that the move to Winston-Salem was the right one. As dean of the College, he did everything from leading a historic overhaul of the undergraduate curriculum to convening the faculty committee that voted to end racial segregation at Wake Forest. As our first and longest-tenured provost, he shepherded our transformation into a nationally renowned university while working to preserve its finest aspects. As “Mr. Wake Forest,” he delivered addresses that affirmed the mystic blend of elements that mark this institution as truly, enduringly distinctive.

“Ed’s leadership sprung from his belief in the inherent goodness of human beings. For him the definition of education was friends seeking happiness together. And happiness was to be found in the pursuit of all that was good, true, and beautiful in life.”

At the heart of that distinction is, as Dr. Wilson so memorably described, a community marked by friendship and by goodness. Ed’s astonishing range of accomplishments did not owe only to his superhuman abilities. Instead, his special gift for connecting with Wake Foresters of all persuasions, helping build a circle of friends (with his wife, Emily, ever at its center) and willing collaborators, has sustained Wake Forest as a place where so many do not merely study or hold a job, but find a meaningful and rewarding home.

As we honor Ed Wilson, our own golden spirit, a few lines from his semester-closing “Fern Hill.” Fellow Blake, Yeats and Thomas alumni will also conjure up our teacher’s inimitable voice:

And as I was green and carefree, famous among the barns

About the happy yard and singing as the farm was home,

In the sun that is young once only,

Time let me play and be

Golden in the mercy of his means,

And green and golden I was huntsman and herdsman, the calves

Sang to my horn, the foxes on the hills barked clear and cold,

And the sabbath rang slowly

In the pebbles of the holy streams.

"Let us raise a glass of the finest to our once & forever ‘Mr. Wake Forest.’”