The story of Provost Emeritus Ed Wilson is the story of a life well lived, an odyssey of 101 years of a self-professed romantic who once proclaimed “What counts in life” are “family first,” a commitment to one’s ideals and a list of riches: poetry, movies, fiction, literature, visual arts and theatre.

The story of the late Ed Wilson is inseparable from the story of Wake Forest.

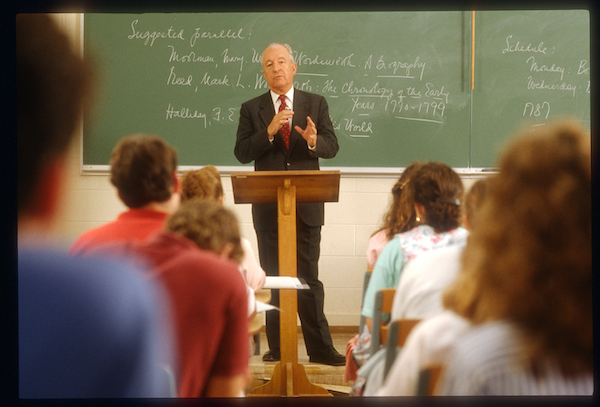

A few years ago, in his deep, mellifluous voice, Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) addressed students in a first-year seminar about the University’s history. He recalled a simpler time when, like them, he was a student — but on the magnolia-lined original campus 100 miles away in the town of Wake Forest, North Carolina.

“Do you know what an epiphany is?” he asked them.

“In my junior year, I went one winter night to a basketball game — I love basketball, by the way — in the gymnasium on the Old Campus. We won the game. I walked home, and the moon and the stars were out. … And I felt so good. Walking down that dirt road, looking at the sky, remembering the basketball game, I said to myself, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful to come back here someday and stay?’”

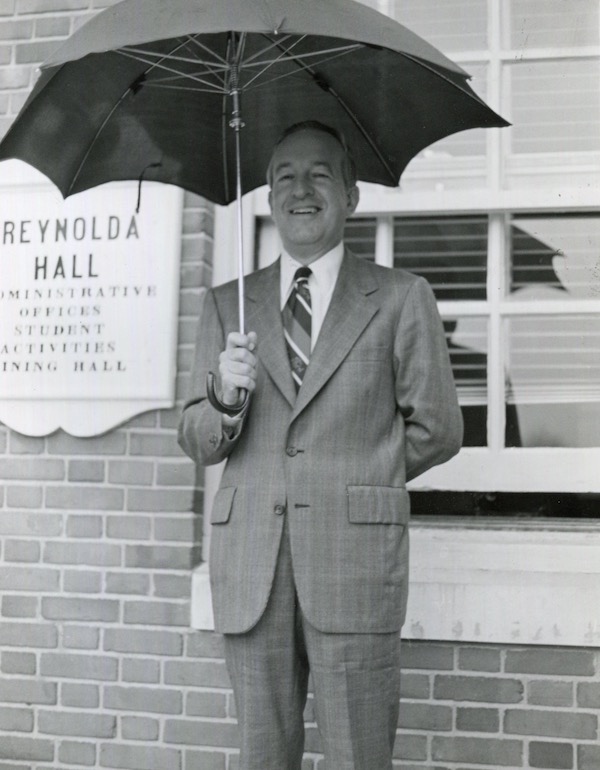

Eventually, he went to war and on to graduate school, but he did return to Wake Forest in 1951 for good. For the rest of his life, until his death on March 13, 2024, he became known as a paragon of excellence, first on the original campus and then, after the college’s move to Winston-Salem, in 1956, on the Reynolda campus of what would become a university.

Wilson’s epiphany to “come back here someday and stay” proved a blessing to Wake Foresters, no matter from which campus they graduated. At some point, others bestowed on Wilson the title “Mr. Wake Forest,” but he was much too modest to be comfortable about it. He once told students he’d prefer to be remembered as a devoted husband, loving father and grandfather.

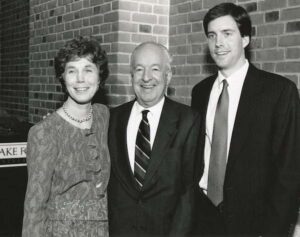

His family graciously shared him: his wife, Emily Herring Wilson (MA ’62, P ’91, ’93), poet, author and scholar in her own right; three children, Edwin G. Wilson Jr. (JD ’93), Sally Wilson (’91) and Julie Wilson, and their spouses, respectively, Laurie Turnage Wilson (’93, MAEd ’94), Carolyn Stevenson and John Steele, and four grandchildren.

From the time Wilson enrolled as a 16-year-old freshman in 1939 until his death at his home in the Faculty Drive neighborhood beside campus, he was associated with Wake Forest for 77 years. During those decades, Wake Forest awarded 93.4% of all degrees bestowed in the institution’s history — reflecting the profound changes from Wake Forest’s founding as a manual labor institute in 1834 with only 16 students.

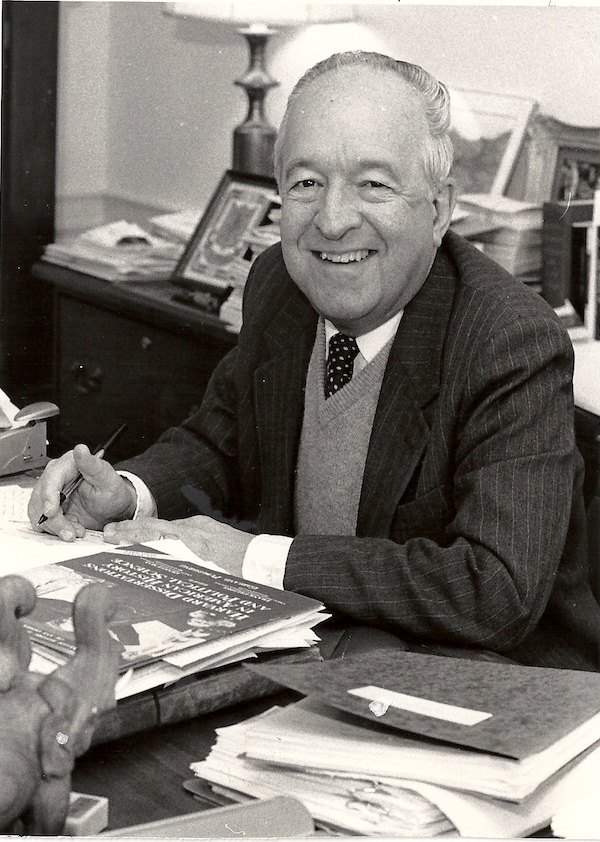

In those nearly eight decades of modern Wake Forest history, Wilson was an undergraduate student, professor, dean, provost, vice president and, always and until the end, encourager and confidant to alumni, faculty, staff, students and friends.

“When I begin to think of the Wake Forest I know and love, two words come at once to my mind: friendliness and honor. I heard them for the first time as Wake Forest words on the night of my own freshman orientation.”

He appealed to humanity’s better angels, urging those who listened to remain constant and true to values most important to him: friendliness, honor and integrity. Wake Forest, he believed, was at its best when combining head and heart.

Wilson was known for elevating virtues in the many eulogies and tributes he delivered for friends and colleagues. He published a book of those remembrances called “Songs of Wake Forest.” At the funeral of President Emeritus James Ralph Scales in 1996, Wilson praised his friend as a noble soul with a noble heart. The words Wilson selected that day from Ralph Waldo Emerson were meant to honor Scales, but they ring true all these years later for Wilson himself: “Wherever there is knowledge, wherever there is virtue, wherever there is beauty, he will find a home.”

Ed Wilson, at right, speaking on the original campus in 1989

WILSON’S DEATH has prompted countless heartfelt tributes and an examination of how one man of generous spirit reflected the quintessence of the highest ideals of humanity and an institution.

“It’s impossible not to be sentimental about Ed Wilson — he evokes in us both our fondest memories of a special time in our lives and also, by virtue of his personal integrity and humanity, a call to our best selves,” said Jeanne Whitman Bobbitt (’79, MBA ’87), Wilson’s former student and a Wake Forest trustee. “But to stop there in either the sentimental or aspirational falls far short of the role Ed Wilson has played as one of the most powerful forces in shaping the Wake Forest that today ranks among the best universities in the country.”

Wake Forest President Susan R. Wente acknowledged his place in history, remembering him as “a man of extraordinary character, grace and wisdom, … a beloved and influential figure at Wake Forest for many decades both as a professor and an administrator.”

Sidebar: Mr. Wake Forest Through the Decades

EDWIN GRAVES WILSON was a man of February, as he liked to say, born Feb. 1, 1923, two days before Wake Forest College celebrated its 89th anniversary. His values were rooted in a mill town called Leaksville, North Carolina, about an hour north of Winston-Salem. Founded in the late 1700s on a bluff overlooking the Dan River, Leaksville merged with neighboring communities in 1967 to form Eden.

Wilson grew up on Hamilton Street with his parents and his three older brothers and older sister. Neither of his parents went to college, but one brother went to the University of Virginia, his sister to Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina (now UNC Greensboro). Wilson’s father was Baptist, his mother an Episcopalian who took the children with her to church. Wilson’s father was an auditor for the textile mill.

Binkley Chapel on the original Wake Forest campus. Photo/Joe Martinez ('06)

Wilson, by his own account, was a quiet, bookish boy who fell in love with movies and literature. Several times a week, he walked the three blocks from his house to the Grand Theater to see whatever was playing — except Mae West movies, forbidden by the Wilson patriarch. The theater’s owner was a neighbor, and he shared the latest movie magazines with young Wilson.

As a boy, Wilson walked along the railroad tracks to the library in nearby Spray. There, he read Thomas Wolfe, Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. He eagerly read adventures about the sea, from Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” to Howard Pease’s “The Ship Without a Crew” and “The Tattooed Man.” At Leaksville High School and later Wake Forest College, he discovered his passion for poetry and Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Alfred Tennyson and Emily and Charlotte Brontë.

“Even now when I read a Yeats poem, I can still hear Dr. Wilson’s voice.”

Wilson traveled the world, for the most part then, only in his imagination. He had been to Washington, D.C., Charleston, South Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee. A family trip one summer to the Outer Banks for “The Lost Colony” play changed everything. The Wilsons decided to stop by Wake Forest at the suggestion of a Leaksville Baptist minister. Even with no students or professors around, Wilson fell in love with the campus.

“There was splendor in the grass that day,” he recounted decades later. “I was captured — for life, as it turned out — by the name and the place alone.”

What joy that young boy must have felt when he received a simple letter from the registrar welcoming him to the freshman class of 1939. Two weeks later, Dean D.B. Bryan wrote to offer a $25 scholarship toward each semester’s $50 tuition.

- Wilson’s acceptance letter to Wake Forest

- Wilson’s scholarship offer of $25 per semester

Wilson, quoting his favorite movie, later recalled how his arrival that first semester was, “in the immortal words of Humphrey Bogart in ‘Casablanca,’ ‘the start of a beautiful friendship.’”

EVEN IDYLLIC WAKE FOREST at that time grew increasingly attuned to the war brewing in Europe. On the day Wilson left for college, news hit about Germany’s invasion of Poland. “I saw the beginning of World War II that very day,” Wilson said. On a large map pinned on the wall of his bedroom in Mrs. Lillian Brewer’s boardinghouse, Wilson traced the Nazis’ march across Europe. In 1941, a friend burst through the door and interrupted Wilson’s studies with news that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor.

Ed Wilson

In those years, classmates answered the draft or volunteered, and professors left for war. As more male students left, women enrolled, which created a true coeducational Wake Forest. The U.S. Army finance school and more than 1,000 officers and soldiers took over many of the campus buildings. The Old Gold & Black ran stories about drives to sell war bonds and collect scrap metal and published regular updates on “the boys in the service.”

DESPITE THE WINDS OF WAR, Wilson savored his life at college. He was one of 412 freshmen in 1939 as total enrollment on campus reached nearly 1,100 students. “Life in this place was sweet and good, and … no man anywhere really needed much more than what we had,” he wrote. Those years were “full of hope and expectation” and spent “in the company of colorful and faithful friends.”

Wilson majored in English and history and distinguished himself as a scholar and campus leader. For the rest of his life, he remembered and discussed the influence of his teachers, especially Broadus Jones (1910, P ’44) and E.E. Folk Jr. (1921, P ’47) in the English department. He listened to the sounds of a Beethoven symphony wafting from the windows of Thane McDonald’s music room, and he heard his first aria, “Che gelida manina,” from “La Bohème,” played on a turntable in a physics professor’s office. (Wilson would become a regular opera-goer and later serve on the Piedmont Opera board in Winston-Salem. One alum recounted how Emily and Ed Wilson, the provost in black tie, stopped by on the way to the opera for a visit at a casual party thrown by former students in the West End. Wilson appeared comfortable in any social circle.)

“I don’t believe in learning as something that is cold and isolated. I believe that learning and friendship and literature and the arts ought to be intertwined into the fabric of our lives.”

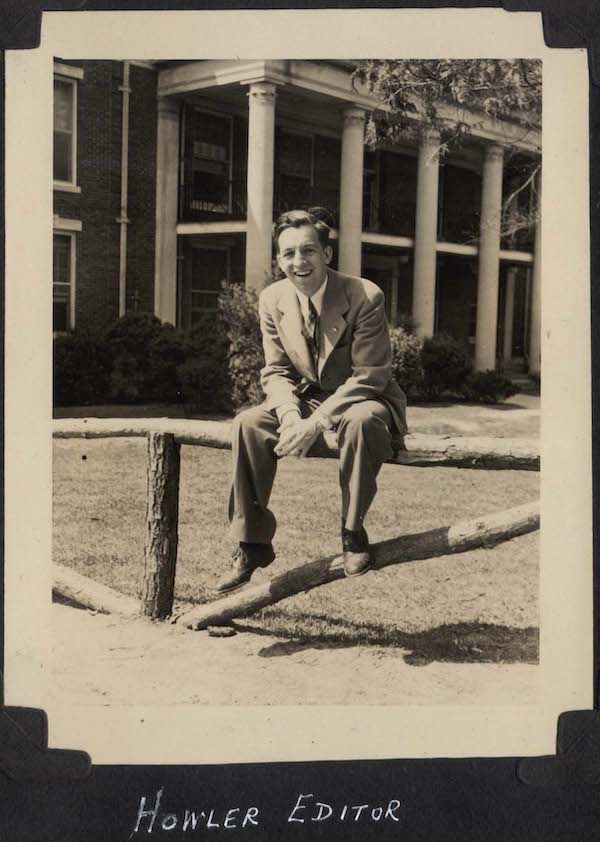

In college, he spent much of his time writing for the Old Gold & Black and The Student literary magazine. As editor of The Howler in 1943, in a hint of what was to come, he penned a dedication to Broadus Jones for having taught the “giants of English literature — Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson and Browning.”

His daily comings and goings confirmed the sweetness of life in a rural North Carolina town. Wilson ate at Mrs. Newsome’s boardinghouse — three meals a day for $22 a month — or he stopped at Shorty’s for a nickel hamburger on the way to the post office to check box 208, a number Wilson easily recalled 70 years later. He met friends for ping pong and bridge at the College Book Store and for movies at the Collegiate and Forest theaters. He joined classmates on the “bumming corner” along U.S. Highway 1 to hitchhike to Raleigh, once for the Wake County premiere of “Gone with the Wind” and a meal of Chinese food.

Students on the “bumming corner” on the original campus

On that small campus, Wilson found what he later described as the heritage of Wake Forest: “discipline and passion, friendship and imagination, wisdom and hope and faith.”

AS HIS GRADUATION APPROACHED and the world was still at war, Wilson did a “very impulsive and spontaneous thing.” He took a bus to Raleigh one morning to join the Naval Reserve. He thought it a better option than what two of his brothers had experienced, fighting on the ground, amid horrors, in Europe. “I’ve always loved stories of the sea,” Wilson once said. “I had never been on a ship. I had never even been in a rowboat. But the idea of going into the Navy had a romantic appeal to me.”

He received a deferment until after graduation, in 1943. Then came four months at Northwestern University’s “midshipmen’s school” and afterward, an assignment as an ensign to a destroyer escort in the Pacific theater.

There, he forged his own war memories, ranging from Okinawa to the Philippines. From his ship he saw the bloody battle of Iwo Jima. He watched as a Japanese kamikaze pilot crashed into a ship nearby. “We were close enough to see what was going on: ‘the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,’” he recalled in a talk with students.

The ship’s location was secret. As communications officer, Wilson found a task on board especially unpleasant. He had to read the love letters that sailors wrote to their wives and girlfriends back home and censor sensitive information.

"Getting into Dr. Wilson’s class was a ‘WFU must do,’ and it merited every bit of its hype.”

By the end of the war, Wilson was a lieutenant junior grade and executive officer aboard the USS Raymond. The ship returned to San Diego, where officers with more seniority were discharged and sent home. In a curious footnote to his war service, Wilson found himself captain of the ship for “one month of glory.” (A framed flag from the USS Raymond has long hung in the Wilsons’ home.)

It was also in San Diego where a newspaper announced that a small college in North Carolina named Wake Forest had accepted an offer from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation to move to Winston-Salem. Far away from the place he held dear, Wilson was heartbroken at the news.

AFTER HIS DISCHARGE from the Navy in 1946, Wilson joined the masses of veterans figuring out what to do next. English professor Broadus Jones laid out a path, inviting Wilson back to the original campus to teach the throngs of GIs returning to school. Wilson taught for a year before going to Harvard on the GI Bill to earn his master’s and doctorate in English.

He said of his time studying at Harvard with Keats scholar Hyder Rollins: “Since I was already a Romantic and already an Anglophile, I was drawn to what I think is the purest expression of literary form — that is to poetry.”

Like Jones, Wilson found happiness in sharing his love of the greats of English literature. With his freshly minted Ph.D., he returned to Wake Forest in 1951 to teach English literature — but not for long. The College, including its faculty and students, would be moving west in 1956. The 100-mile move became a seminal event for all concerned.

Wilson felt a deep sense of responsibility to ensure that the atmosphere and friendliness of the original campus be transplanted to the new home in Winston-Salem. As sentimental as Wilson was about the original campus of his youth, he also knew that education was about the future, and he had a part to play. “Seldom can anyone say with assurance, ‘This is it — the beginning of a new era!’” his mentor Broadus Jones said at the September 1956 convocation on the “new campus.”

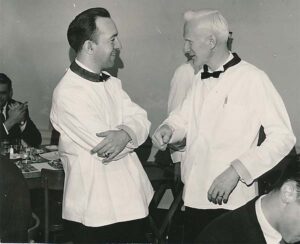

Wilson helped usher in that era. In 1958, he became acting dean of the College and in 1960 was named dean at the dawn of a tumultuous decade on U.S. college campuses, marked by Civil Rights marches, Vietnam War protests and challenges to societal and cultural norms. In the early 1960s, unlike some faculty, students, trustees and alumni, Wilson supported ending racial segregation at the College. One campus poll showed 55% of students voting against integration. Other students felt differently, organizing the African Student Program to raise money to bring an African student to campus to enroll. In 1961, the faculty approved a resolution encouraging trustees to allow Black students to be admitted. In 1962, the trustees agreed, and Ed Reynolds (’64), from Ghana, became the College’s first Black student. He found allies on campus, including Wilson, who, as Reynolds recalls and a photograph documents, participated in a fundraiser on Reynolds’ behalf: Wilson collected money by waiting tables in the Magnolia Room. In those early years of the 1960s, despite racial tensions on campus and in the city, Wait Chapel hosted the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and contralto Marian Anderson. When students marched on then-President James Ralph Scales’ house in 1970 to protest the Vietnam War, Wilson and other faculty members sat down with the students to hear their concerns.

- Wilson and University Chaplain Ed Christman (’50, JD ’53, P ’84, ’85) waited tables in the Magnolia Room and pooled their tips to help Wake Forest’s first Black student, Ed Reynolds (’64), of Ghana.

“I have two strong hopes: one, that all of you who love Wake Forest will remain understanding and loyal; and two, that Wake Forest will continue forever to be what it was when I first saw it and what it is today: a place where reason, imagination and faith flourish, a place eternally and fearlessly in pursuit of the truth, a place which is open, hospitable, generous, loving and free.”

Wilson’s love for the arts showed in his support of the founding of what is now the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art. Wilson accompanied students on the first art-buying trip to New York in 1963.

In 1967, the same year Wake Forest College became Wake Forest University, Wilson became Wake Forest’s first provost. With President Scales and later with President Thomas K. Hearn Jr., he helped Wake Forest gain recognition beyond the regional excellence the school had long enjoyed.

He shaped the University’s academic curriculum, programs and faculty. As an academic leader, he expanded graduate programs, including the graduate School of Business, and started an interdisciplinary honors program. He attracted potential faculty members who first had to pass what some called “the Ed Wilson test” — they needed to enjoy teaching and be committed to the well-being of students.

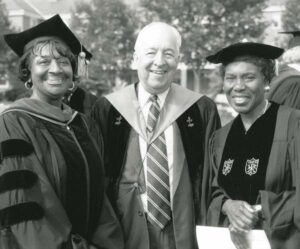

He hired women and Black faculty members and supported their promotions, including Elizabeth Phillips and Mary Frances Robinson, the first women in the College to become full professors. In 1974, Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74, P ’23) and Dolly McPherson became the first Black tenure-track professors. In the 1980s, Wilson hired the first Reynolds Professors, including poet Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77), who became a longtime friend.

The University’s residential houses for study abroad bear Wilson’s mark of promoting exceptional opportunities for students: Casa Artom in Venice, established in 1971, and Worrell House in London in 1977. Wilson had a special fondness for Worrell House, funded by his friend and former classmate Gene Worrell (’40, L.H.D. ’79).

“Absolute legend. Mr. Wake Forest was one of the greatest men I ever got the pleasure to meet. He lived life to the fullest, and inspired so many students, including myself.”

During the 1970s, campus was “alive … with a creative passion,” Wilson once wrote. Prominent politicians, authors, journalists and musicians regularly visited campus, and the Wilsons entertained many of them in their home.

Those who knew Wilson speak of how comfortable he was with anyone from any station in life, no matter how famous. Wilson told a story of how Harold T.P. Hayes (’48, L.H.D. ’89, P ’79, ’91), then editor of Esquire, encouraged his circle of New York friends to become involved with the University. One of them was National Book Award winner Ralph Ellison, author of “Invisible Man.” Ellison joined the University’s board of visitors in 1972 and later accompanied Wilson on a fundraising visit to the Henry Luce Foundation in New York. Two-time National Book Award winner and renowned poet A.R. Ammons (’49, D.Litt. ’72) was a dear friend of the Wilsons — Ed Wilson taught him freshman English on the original campus. Ammons was always a welcome visitor at the Wilsons’ home.

Wilson with the late Reynolds Professor of American Studies Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ‘77)

It’s no surprise that — with Emily Wilson as a successful poet and Ed Wilson as a beloved professor of British Romantic Poets and Blake, Yeats and Thomas —Wilson backed a daring idea endorsing poetry writ large. As provost in the mid-1970s, he became the original benefactor of Wake Forest University Press, now the major publisher of Irish poetry in North America.

Wilson with the late Chaplain Emeritus Ed Christman (‘50, JD ‘53)

None of the advances in Wake Forest’s new era can be attributed to any one person. Wilson would be the last person to claim credit, let alone sole credit, for anything. Throughout his tenure as dean and provost, Wilson worked with a cadre of trusted colleagues — many of whom lived near him in the Faculty Drive neighborhood — including Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88), John Williard, Lu Leake, Mark Reece (’49, P ’77, ’81, ’85), Bill Starling (’57), Ed Christman (’50, JD ’53, P ’84, ’85), Russell Brantley (’45, P ’72), Henry Stroupe (’35, MA ’37, P ’66, ’68) and Gene Hooks (’50, P ’81). They were mostly fellow alumni and all of them his friends.

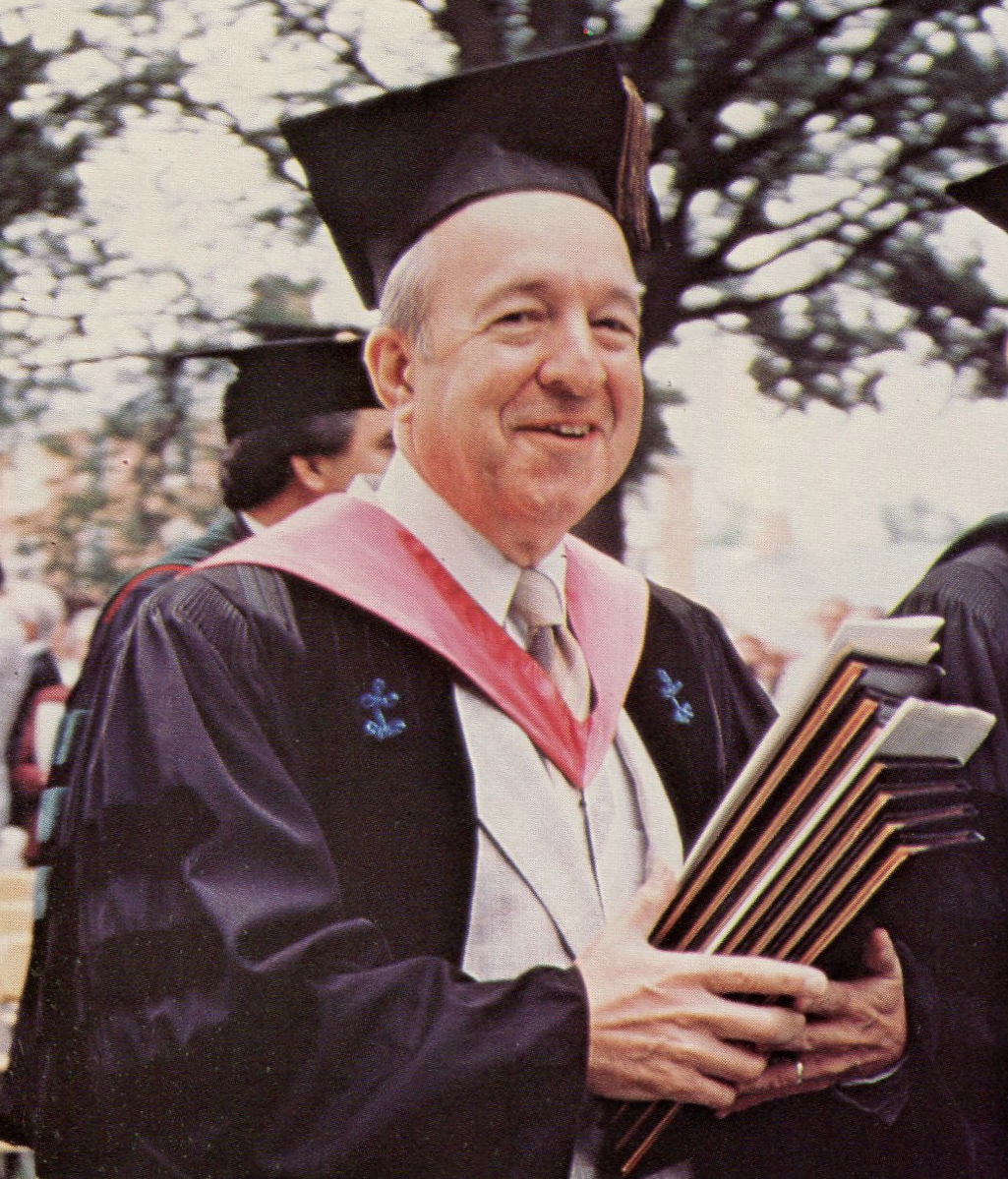

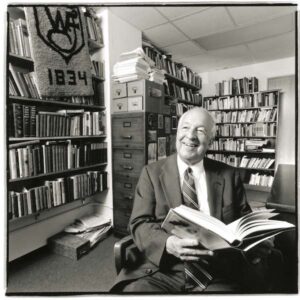

Wilson retired as provost in 1990 to become vice president for special projects and traveled around the country to tell Wake Forest’s story during a capital campaign. He returned to the administration in 1998 as a senior vice president in the provost’s office. Though he officially retired in 2002, he continued, for years, dressed smartly in coat and tie, to go to his office in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library. Alumni popped in to see him there or wrote him long, newsy letters. Homecoming and events around the country were occasions for alumni to mob “Mr. Wake Forest” and stand in awe of his uncanny ability to remember names and faces and treat all with kindness and respect.

Friends celebrate Wilson’s 100th birthday.

Friends and alumni often trekked to the home the Wilsons built in the 1960s in the woods on Timberlake Lane. They arrived with gifts of homemade cookies, cherry jam, pound cake, cinnamon rolls and ice cream. Drawing chairs close to Wilson’s in a den filled with books and family photos, the visitors and Ed Wilson talked about family, former students, literature, film classics, politics and the latest basketball game.

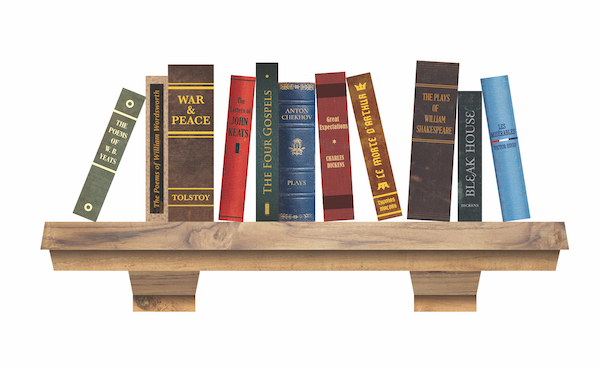

Marcus Keely (’10) once asked Provost Emeritus Ed Wilson which books would comprise his “ideal bookshelf.”

WILSON TURNED 100 IN 2023, an occasion that warranted celebration, blog posts and social media tributes. A line of people who wished to greet the provost emeritus in the library stretched into a hallway. This year, to mark his 101st birthday, students tied gold ribbons around trees on campus.

- Alumni, professors, staff and others wished Wilson a happy 100th birthday in 2023.

- Students tied gold ribbons around trees on campus to celebrate Wilson’s 101st birthday.

Forty-one days later, Wilson would die at home, according to a family member, “peacefully.”

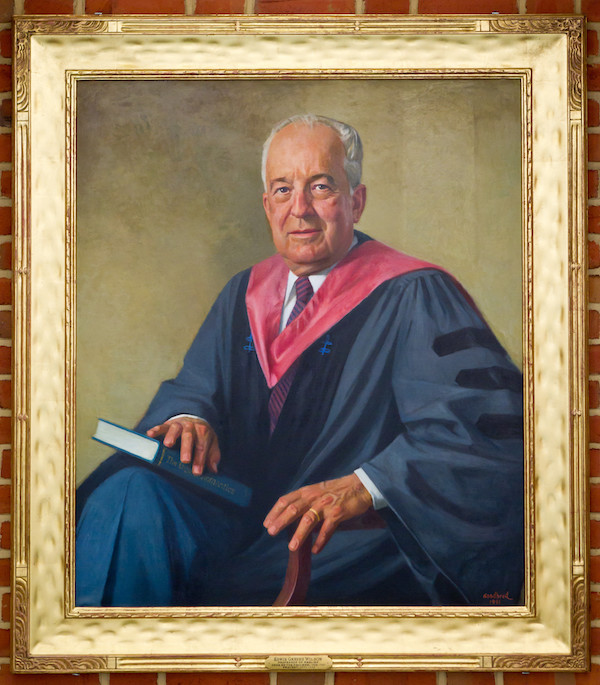

Wilson is no longer here physically, but he is here in ways that will last. Younger graduates did not have the pleasure of taking his classes, but they gaze up at his portrait in the Wilson Wing of the library, arguably the most popular building on campus. Older graduates share their memories and stories of having known a true son of Wake Forest who stood for the best of the ideals of the original campus and the new.

“Treasure this moment, treasure Wake Forest. … To me, one of the happy facts about Wake Forest is that on that day, way back when I heard about the new school for the first time (in 1939), the two words that leaped out were ‘Wake’ and ‘Forest.’ There is something wonderful about that name, Wake Forest. It suggests waking up to life itself at its best, and it suggests something green and verdant that lasts as far as to the years to come.”

There are Ed Wilson’s words. They live on.

Wilson spoke at the Founders Day convocation in 1992, before the dedication of the Wilson Wing. He recalled people in history who had inspired him with ideals and imagination: the poets John Keats and Emily Dickinson, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Nobel winner Elie Wiesel and Rev. King. Wilson quoted King: “One day we will learn that the heart can never be totally right if the head is totally wrong. Only through the bringing together of head and heart — intelligence and goodness — shall man rise to a fulfillment of his true nature.”

And then Ed Wilson shifted from the lofty to the humble by quoting from the wisdom of a children’s book. In “Charlotte’s Web,” a dying spider addresses Wilbur the pig. “You have been my friend,” Wilson recalled. “That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you.”

“I would conclude this morning,” Wilson continued, “by saying with Charlotte, to all of you: my family, my colleagues, my students — you have been my friends. That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you.”

"Ed Wilson’s legacy must rest most on that generosity of spirit for the concentric worlds — family, colleagues, alumni/ae, Wake Forest, North Carolina — through which he walked with confidence made humble, with complexity made simple by love.”