On the women’s basketball team, Porsche Jones (’06) made an impact at Wake Forest, despite her 5’2” frame. The record-breaking point guard still is the Demon Deacons all-time leader in assist-to-turnover ratio and the most steals in a game, among other high notes.

But when she finished her career, she was in a state familiar to many athletes not going pro — she had no plans for her own future. “I’m the perfect example,” Jones says. “I never thought (about) what is going to happen when the basketball stops bouncing. I never focused on any other skill sets or any other passions. I was involved in a lot of things, but I didn’t know what I was going to do next.”

Porsche Jones ('06) in 2005 in Joel Coliseum <br /> Header image: Women's basketball game against UNC-Chapel Hill in Joel Coliseum on Jan. 27, 2006

So she focused on what she’d been doing — basketball. And she found a calling — helping kids achieve what she did at Wake Forest, earning a college degree while playing the game they love. Through her program, which emphasizes not only sports skills but also academics and community service, Jones and other coaches using her system have, so far, helped more than 85 youth athletes attend college with scholarships.

None of it surprises Dwight Lewis (P ’24, ’26), Wake Forest’s associate athletic director for student-athlete engagement and diversity, equity and inclusion, who has known Jones since she was a high school basketball player in Winston-Salem. “She always had the spirit of giving back,” he says.

Jones coaching high school students for a college showcase event

‘We need this one here at Wake’

As a young girl growing up in East Winston, Jones honed her basketball IQ by playing with the boys in her neighborhood. “She was feisty; she was tenacious,” says Josh Howard (’03), the Wake Forest Sports Hall of Fame basketball player who went on to play in the NBA. The two grew up together; Jones’ uncle married Howard’s aunt.

Jones played at Carver High School, where her team won two state championships. Wake Forest’s Lewis remembers the sold-out crowd who came to see Jones play in high school and Jones’ composure and maturity at the first meeting. “She shook my hand the way you’re supposed to shake a hand, and she looked me right in the eye and introduced herself,” Lewis says. “And I thought, ‘Yeah, we need this one here at Wake.’”

Jones with her mentors. From left, Dwight Lewis, Porsche Jones, high school coach Alfred Poe and college coach Charlene Curtis.

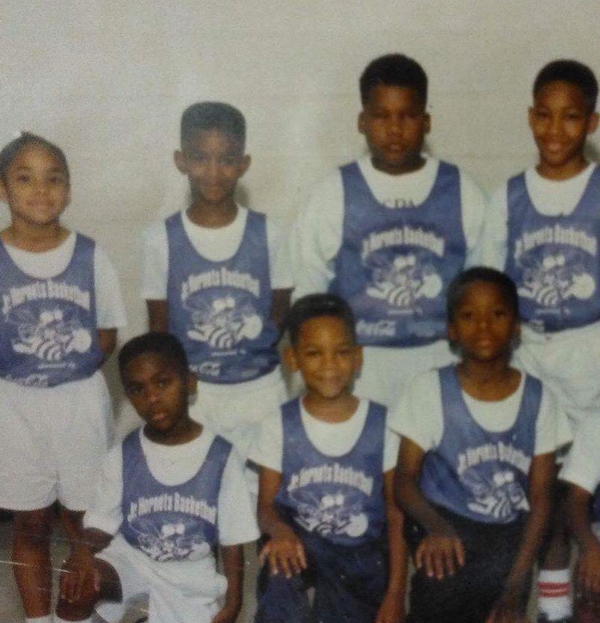

Jones (left) on a youth basketball team with all boys

Raised by her paternal grandparents, Jones didn’t limit her focus to basketball in her early years. Her grandfather, Robert Scales, was a leader in his church and local civil organizations. Her grandmother, Manderline Scales, was a longtime educator, serving as assistant vice chancellor of student affairs at Winston-Salem State University and credited with launching the school’s Spanish department.

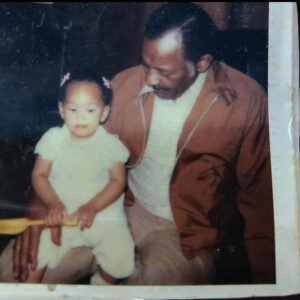

- Jones with her grandfather, Robert A. Scales

- Jones with her grandmother, Manderline Scales

Jones grew up attending community meetings and speaking at church. Her grandparents, who have both passed away, instilled in her the importance of being disciplined and driven and helping others succeed. Before Jones arrived at Wake Forest, she’d seen its Pro Humanitate motto lived out at home, she says. “It’s a thought process as well as it’s just a way of life that I witnessed.”

Jones' grandparents, Robert and Manderline Scales

Giving back was central to her student experience at Wake Forest as an athlete volunteering with the Santa’s Helper program or speaking to grade schoolers or in her sorority, Delta Sigma Theta. “Wake Forest has done amazing things for me not only from an educational standpoint, but (also with) the exposure to love and taking care of others,” she says.

A calling to help

The nearly year-round girls travel basketball team she launched after graduating was simply an extension of that calling to help others, nurtured at home and Wake Forest.

As a teenager, Jones hadn’t understood how college athletic scholarships worked until she was in the position to get one. “I wanted to be able to help young girls navigate that process, help parents navigate that process and to be able to be a beacon of light and a connector to help people navigate what they truly want,” she says.

An early BOND basketball team

Jones admits she was a “hard coach” to be around. She didn’t permit any messing around. Phones were confiscated during tournaments. Practices were serious, focused on learning skills and drills. Off the court, the team was always volunteering, and sometimes Jones gave assignments, among them a two-page paper during Black History Month.

“She was always on them about their academics, because she knew that if they weren’t academically sound, no matter how good you play, you’re not going to make it,” remembers Donna Claytor, whose daughter Dominique was on the team.

From the start, Jones told players that her goal was to get them what she’d enjoyed — a college scholarship to play basketball. By the time the girls graduated from high school in 2015 and 2016, all 18 had full rides to college.

A BOND team

For Claytor’s daughter, it was to East Carolina University, where she earned an undergraduate degree in business, and then Tennessee State University, where she earned a master’s degree. Basketball scholarships paid for both. Dominique Claytor is now in officer training school in the U.S. Navy. Another player recently earned her dental degree, and one is getting ready to go to medical school.

Just as the girls grew up through that process, from fourth or fifth grade to high school, Jones did, too. She earned a master’s in rehabilitation counseling from Winston-Salem State and began a career as a community health services manager at Novant Health. She works to eliminate barriers to health-care access, including taking a 38-foot mobile cruiser across parts of Winston-Salem to provide free health screenings.

In the meantime, Jones has built on her winning coaching formula. When her girls team moved on to college, Jones stopped coaching and let other coaches bring their teams, for both boys and girls, under her program. Young athletes are still winning scholarships through the program, but it has a broader mission now, part of Jones’ BOND Cares nonprofit. BOND stands for Building on New Development.

Jones and her "BOND family" for a back-to-school event

“When I first started, it was about winning; it was about being the best; it was about being dominant,” Jones says. “And over the years, I’ve understood that sometimes kids just need a place to call home. … So that’s what BOND has become.”

The emphasis also is on grades and conduct, ensuring that athletes are in good standing at school. And BOND works to support parents and family needs. At a back-to-school event last year, BOND distributed 300 bookbags and 300 pairs of shoes.

Jones has also concentrated her efforts in the low-income neighborhoods around East Winston. BOND teams practice on courts in the neighborhood. And she runs BOND Events, a for-profit organization that holds about 48 tournaments each year, mostly in east Winston, to help support the community’s businesses. Thousands of patrons — players and their families and coaches — visit local restaurants, stores and other businesses as they travel into the area for tournaments.

An early BOND team

“It’s a great opportunity to shine a light in a positive way on the side of town I grew up in,” Jones says. “People have to eat on that side of town, they have to get gas on that side of town, they have to experience a side of town that I think they otherwise would not. That point is very important to me.”

‘In my DNA’

On top of supporting youth teams, running tournaments and her full-time job, she also owns a trucking company, JMAC Prestige Hauling LLC, with a former Carver football coach, James McMillan. McMillan had started the company earlier and was driving the truck to Carver, where Jones had been working as a coach. Jones is involved in behind-the-scenes logistics work for the firm, working on bids, contracts and invoicing.

“I did my due diligence on it, and I realized that there weren’t many business owners who looked like me in that particular industry,” she says. “So, I saw it as a challenge just like playing basketball, just like being on the Dean’s List at Wake Forest. … I saw a gap that I thought would be interesting for me to be a part of.”

BOND boys' teams

Howard, the Hall of Famer, sees a bigger plan behind all of Jones’ roles as entrepreneur, business owner and community leader. “She’s just giving people an opportunity to touch, feel, see what she’s done and give them that drive to go out there and do it themselves,” says Howard, now the head men’s basketball coach at the University of North Texas at Dallas.

Jones doesn’t disagree, and she doesn’t shy away from the title of role model. Her grandparents prepared her for the job. “It’s just something that’s in my blood, in my DNA,” she says. “Even if I wanted to stop, I don’t think I could.”

Sarah Lindenfeld Hall is a longtime North Carolina-based journalist, former staff writer for the Winston-Salem Journal and The (Raleigh) News & Observer and founding editor of WRAL-TV’s popular parenting website. Today, she’s a freelance writer, regularly diving into stories about interesting people and parenting, health, education, business and technology topics.