Former football player and track star Steve Brown (’91) is watching the 2024 Paris Olympics with more than a passing interest. A world-class hurdler, Brown pursued his own Olympic dreams for 20 years, coming agonizingly close to making the U.S. track team in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics before representing Trinidad and Tobago, his father’s native country, in the 2000 Sydney Summer Olympic Games.

A native of Washington, D.C., and a high school hurdler, Brown had dreamed of going to the Olympics since he was young. He didn’t receive any college scholarship offers for track and only one Division I football offer — from Wake Forest. He would go on to excel as a four-year starter and standout wide receiver.

But he harbored larger ambitions. When he would walk by the athletic trophy cases, then in Reynolds Gymnasium, he noticed that there were few ACC or national awards for track. He decided he would change that.

He walked on to the cross country and track teams, coached by John and Francie Goodridge, and was soon bringing home ACC and NCAA awards and was Wake Forest’s first All-American in track. He was a four-time ACC champion — twice winning the 110-meter outdoor hurdles and twice winning the indoor 55-meter hurdles — and a two-time All-American in 110-meter hurdles.

Steve Brown ('91) at the 2000 Sydney Summer Olympic Games

As a senior, he received Wake Forest’s Arnold Palmer Award for the top male student-athlete. He was named to the ACC’s 50th Anniversary Men’s Outdoor Track & Field team in 2002 and was inducted into the Wake Forest Sports Hall of Fame in 2009.

Brown, 55, still marvels at his life journey. “Every one of the opportunities I’ve had, there’s no way to explain. My life is like a Disney movie because there’s no way I came up with all this stuff. You have to follow your dreams. Whether or not you succeed, the journey is incredible. I’m living proof of that.”

Brown, who lives outside Atlanta, founded the Steve Brown Academy, which offers programs to help student-athletes succeed in sports and beyond.

Wake Forest Magazine Senior Editor Kerry M. King (’85) spoke with Brown about his Olympic journey, the life lessons he learned along the way and why he’s passionate about what he’s doing today. Excerpts from their conversation have been edited for length and clarity.

Kerry King: What are some of your lasting memories from the 2000 Sydney Olympics?

Steve Brown: Walking into the Olympic Stadium … the opening ceremony was just what I had watched growing up, and I’m taking pictures with the tallest Asian man (Yao Ming) I’ve ever seen in my life. They give the athletes pins to trade with (athletes from) other countries, so I got a ton of pins. There are the moments that no one at home sees, like in the Olympic Village with all these (athletes from) different countries wearing their garb. Everyone had worked to be there, be it one or two years or an entire lifetime, or for me 19 years. I had worked towards that — I was 31 — since I was 12 years old. And I liked watching the trials of the different sports. (On television) you see the people who make the team, but you don’t see the people who just missed making the next round.

KK: I’ve heard you say that everyone should aspire to be an Olympian. What do you mean by that?

SB: You have to strive for your dreams because the journey is worth it. Your Olympics could be starting a business. It could be being the first in your family to graduate. I was fortunate to compete in one (Olympics), but there was a bunch of stuff that I failed at, and there were all these other cool things that happened in the process. The journey is amazing. It’s worth it, and you’ll inspire your kids and folks around you. And you might end up doing something great.

Steve Brown in front of the Sydney Opera House in 2000 <br />

KK: What are you looking froward to watching at this year’s Olympic Games?

SB: The United States hasn’t won a gold medal in the women’s 100-meters since 1996. There’s a chance for Sha’Carri Richardson to do that. Grant Holloway is going for his first Olympic gold (in the men’s 110-meter hurdles). There’s going to be some great races. The basketball team looks to have a tough draw. Swimming and gymnastics are always exciting. And there’s break dancing this year? I’ve got to watch that. And I will also be cheering for the 18 athletes from Trinidad and Tobago competing in three events (track and field, cycling and swimming).

KK: Do you have a special routine for watching the Olympics?

SB: Of course, I do! I visit the NBCOlympics.com schedule page before the start of the Games and determine what sports I want to view each day and when they are televised (streamed). I add them to my daily calendar throughout the “16 Days of Glory” starting with watching the Opening Ceremonies in its entirety. Typically, I will watch by myself during the day and with family in the evening. Staying up late is a must!

Steve Brown was a four-year starter at Wake Forest and the team's second leading receiver his last three years.

KK: You’ve had an incredible life journey. You visited the School of Business last year and spoke to students. You told them: “Someone is making a sacrifice for you to be here.” A big part of your message is gratitude. Did that come from your parents?

SB: My brothers and I were fortunate to have two great parents. My mother (who was a paralegal) is from rural South Carolina. My father (a dentist) was from Trinidad and Tobago. They came from humble beginnings to make a better life for themselves and their family. They gave us a blueprint that if you want something and you’re willing to work for it, then you should go for it. I’ve been very blessed and fortunate.

KK: You also said something else in that same talk that I found interesting. “Once your ‘why’ is greater than your ‘how,’ you can work for something greater than yourself.” What do you mean by that?

SB: That was from (football teammate) James DuBose (’90). He said, “If your why is greater than your how, you’ll figure it out.” We have a tendency that something has to be perfect in order to move forward. No. Your “why” has to be what drives you. You’ll make mistakes along the way, but you’ll figure it out. Once you get your “why” and your purpose, you’re going to have a much more enriching life and be able to help more people. Don’t stop just because you don’t know the “how.”

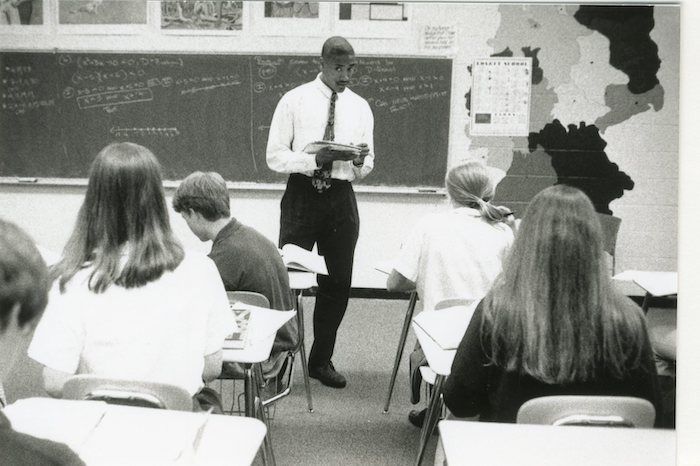

Steve Brown teaching a high school math class at The Lovett School in Atlanta, circa 1993

KK: When you came to Wake Forest, you decided to major in math. I mention that because math has played a big part in your life, right?

SB: In high school, I liked math. My math teacher, who was also one of my football coaches, said, “You might want to go to Wake Forest and study math.” It’s amazing how a seed is planted. I used to fall asleep at Wake Forest games — that I was playing in, when I was on the sidelines. I loved biographies and history, but I couldn’t read past three pages without going to sleep, so I started taking math courses. (Brown was diagnosed with narcolepsy at 48). Sarge (longtime athletic equipment manager David Tinga) suggested that I get certified to teach. “You can always find a job teaching math.” And he was right. (After graduating, Brown played briefly for the Chicago Bears and in the Canadian Football League before becoming a math teacher and assistant football coach at West Forsyth High School in Clemmons, North Carolina.)

KK: I’ve heard you say that you were prejudiced against white people when you came to Wake Forest.

SB: Growing up, no one in my family taught that mentality. But your friends and your peers know everything. And the message was constant: White folks don’t look after folks like us. I grew up in the Episcopal Church, went to a Catholic elementary and middle school and a Jesuit high school, so that wasn’t being taught there. I get to Wake Forest, and it was the same. “Why are you inviting me to your house for dinner? That’s not supposed to happen.” I had to learn the hard way that I had to look at people’s actions. I was asking people to look at my actions, but I wasn’t doing the same thing. I was being hypocritical, but experience is an incredible teacher.

KK: Who were some of the folks who were reaching out to you, inviting you to dinner?

SB: My Deacon football “parents,” Betty and Bobby Faulkner; Julie Davis Griffin (’69, P ’00) and Cook Griffin (’65, P ’00); Dr. (Larry) Hopkins (’72, MD ’77, P ’12, and Beth Norbrey Hopkins (’73, P ’12); Mutter Evans (’75); Leah McCoy in education; Richard Carmichael (’64, P ’03) in the math department was my adviser; and Gil McGregor (’71, P ’16). Bill Starling (’57) would come down (to Atlanta) every year for a college fair. That foundation has lasted me for going on 40 years.

I don’t have many regrets, but one of the regrets was I didn’t know Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77) taught at Wake Forest until two years after I left. And I’m thinking, “Are you kidding me?”

KK: Gil McGregor mentions you in his new book, “The Blind Truth: Lessons From a Basketball Life.” (McGregor was one of the first Black basketball players at Wake Forest and an athletics-academic adviser when Brown was in school.) What was your connection?

SB: He put me in touch with LeRoy Walker (LL.D. ‘93) (the longtime track coach at North Carolina Central University in Durham, North Carolina, and later the school’s chancellor). He was the first African American president of the U.S. Olympic Committee and coach of the first back-to-back Olympic gold medalist in the hurdles, Lee Calhoun, in ’56 and ’60. Gil asked him, “We have a freshman who’s a hurdler who needs some help. Would you mind working with him?” I started driving two hours one way (to Durham) to work with him. That led me to working with his protégé, Charles Foster (the top-ranked hurdler in the world at one time).

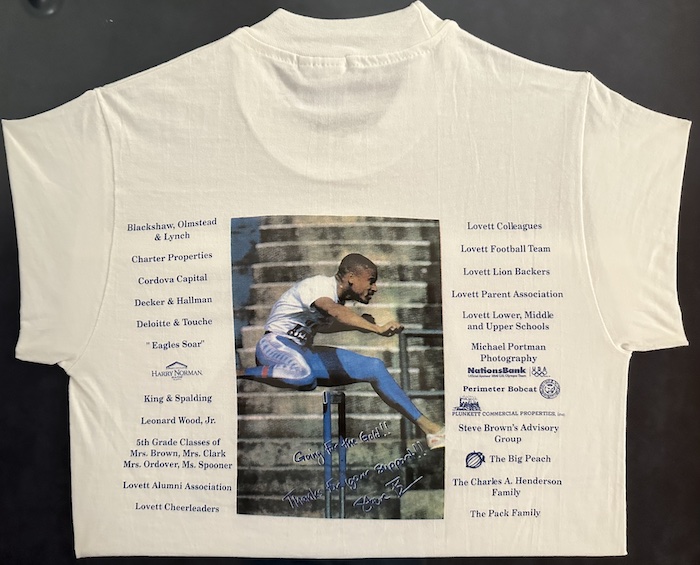

Students at The Lovett School sold special T-shirts to raise money for Brown's training before the 1996 Olympics.

KK: I know you tried out for the ’88 Olympics, but you didn’t make the team. You decided to skip the ’92 Olympics and set your sights on the ’96 Games in Atlanta. You moved there to train, but you needed a job. Rick Decker (’68, P ’00), who had two daughters at The Lovett School in Atlanta, helped you get a job there teaching math. Did you know him before?

SB: No. That’s the thing about the small but extensive, Wake Forest network. Wherever I went there were always Wake Forest alumni. (At Lovett) I was the only Black male teacher in the entire school, pre-K through 12, famously known for denying Dr. King. (The school denied admission to Martin Luther King Jr.’s son, Martin Luther King III, in 1963.) But everybody welcomed me with open arms.

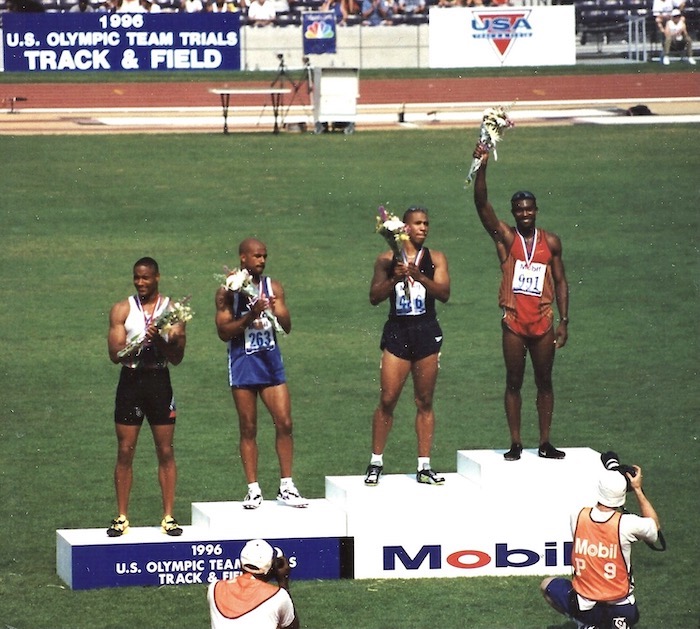

KK: You missed qualifying for the U.S. track and field team by 7/100th of a second for the ’96 Olympics. Tom Brokaw interviewed you for NBC News on your plans to start training for the 2000 Olympics. What kept you motivated?

SB: He said the reason he was doing the story was it was easy to do a story on a gold medalist or a world record holder, but there’s hundreds and thousands of athletes who train just as diligently and don’t make it. What happens to them? I learned that I could compete with these guys. I finished that year ranked No. 10 in the world and six of the top 10 were in the United States. Now there’s tangible evidence that I can perform on this level. You can do whatever you want in life, to a point. I’m not going to be a neurosurgeon. I’m not going to be Randolph Childress (’94, P ’20) hitting the game-winning three. Find out what you’re good at. You may not even know, but ask people around you and put all your energy there.

Steve Brown, far let, finished fourth in the 1996 Olympic trials and was the first alternate at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.<br />

KK: In the run up to the 2000 Games, you advanced to the semi-finals during the trials for the U.S. World Championship team, but were disqualified after two false starts. How did you find a way forward after that disappointment of not making the U.S. team?

SB: I hadn’t been that hurt since my father’s funeral. An hour later, I couldn’t even walk. I had a tear in my hamstring. I’m devastated. Then a buddy who ran for Trinidad said, “You ever thought about representing your dad’s homeland?” My father became a naturalized (U.S.) citizen after I was born. First-generation offspring can become dual citizens (in Trinidad and Tobago), and I was granted dual citizenship in 1998.

I walked into the Olympic Stadium in Australia in 2000 under my father’s colors. The last time I saw my father was at Senior Day (Brown’s last home football game at Wake Forest in 1990. His father died before he returned home for winter break.) That was another example of Wake Forest and a whole bunch of people coming to my aid during a very difficult time. Fast forward (to 2000) and to have the opportunity to represent his homeland was beyond priceless.

Steve Brown, second from right, was the flag-bearer for Trinidad and Tobago at the Pan American Games in Winnipeg in 1999.<br />

KK: You were very sick with the flu in Sydney and didn’t advance past the second round. After chasing this Olympic dream for 20 years, how did you change your mindset to consider other things that you can do?

SB: I didn’t. I went through four to six years of undiagnosed depression. When you compete at that level — and let’s be honest, I started being treated differently in fourth grade because I could run a little faster, jump a little higher — it’s a difficult transition. One of the things I considered studying in my doctoral work was the relationship between athletic identity and identity foreclosure. What that means is, if I put all my eggs in the athletic identity basket with the hope of getting a D-1 (Division 1) scholarship or (making) the league (NFL), when it’s time to transition away from that, that can be very difficult if you don’t know more about your identity. There are a lot of athletes who go down the wrong road because they don’t know what else to do.

KK: How did you turn that around?

SB: Therapy works, and I was fortunate to have a support system; having people around who cared enough not to give up on me because you can go to a dark place very fast. I had a foundation (academics) that I could fall back on. I’m not the most religious guy in the world, but I’m a pretty spiritual dude. And I just asked: “Why me? Why did you send me to Wake Forest? Why did I become a math teacher? Why did I go to the Bears and Canada and the Olympics? Why did I go to business school?” And the message kept coming back. You are going to be in a position to help someone who has similar aspirations. Every time I wanted to give up, it was like, “Dude, you don’t get it. There is a divine plan beyond you.”

Steve Brown with the Lovett School Lower School Orchestra in 2016.

KK: You went on to earn an MBA from Duke, work on Wall Street and eventually return to The Lovett School to work in admissions and financial aid until last year, when you founded the Steve Brown Academy. (Brown is also completing his Ed.D. at the University of Pennsylvania.) What do you hope to teach the student-athletes you’re working with?

SB: There’s a program called Breakthrough Collaborative in 24 cities. It’s a six-year program to help kids from underserved communities get to college. I want to mimic that for student-athletes, wherever they fall on the athletic lifecycle, and not just those from underserved communities. I want to help athletes succeed outside of athletics. They know how to set a goal and how to deal with success and failure. They have a skillset that is transferable into any classroom or any boardroom.

The book “I Dare You” (by William Danforth) led me to create and trademark the Complete Your Square curriculum. Completing the square is a way to solve a quadratic equation. Complete Your Square makes up the body, the brain, the heart and the soul. The body (athletics), you have to be healthy to perform at your best. The brain (academics), you have to be a lifelong learner. The heart (character education), you have to give back to your community through sound decision-making. The soul (servant leadership), you have to understand that service to others is the greatest example of Pro Humanitate. Too often, you’ll find yourself spending a significant amount of time on one of those, which causes an imbalance. If you can Complete Your Square, your probability of success will rise.

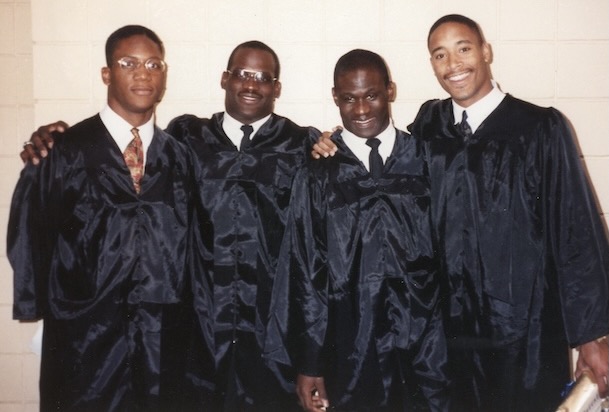

Graduation 1991, Steve Brown, far right, with teammates Phil Barnhill, Levern Belin and Warren Belin