Technological advances have sped up so much of our communication and daily chores, from shopping online to texting and paying bills. But what if, in our race against time, it turns out that technological progress isn’t really helping?

Nine years ago, Stuart Whatley (’07) was so drawn to that argument by Nicholas Agar, an ethics professor in New Zealand, that Whatley included it in a piece he wrote on the “myth of busyness” for HuffPost, where he worked as an opinion editor.

Whatley’s point of view often debunks conventional thinking. In one recent essay, “Toward a Leisure Ethic,” he argues against adding on projects for work’s sake, instead advocating for taking more control of your time and energy.

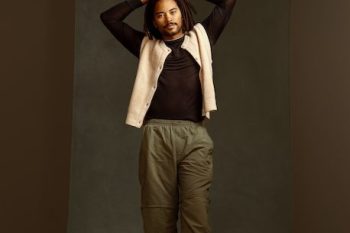

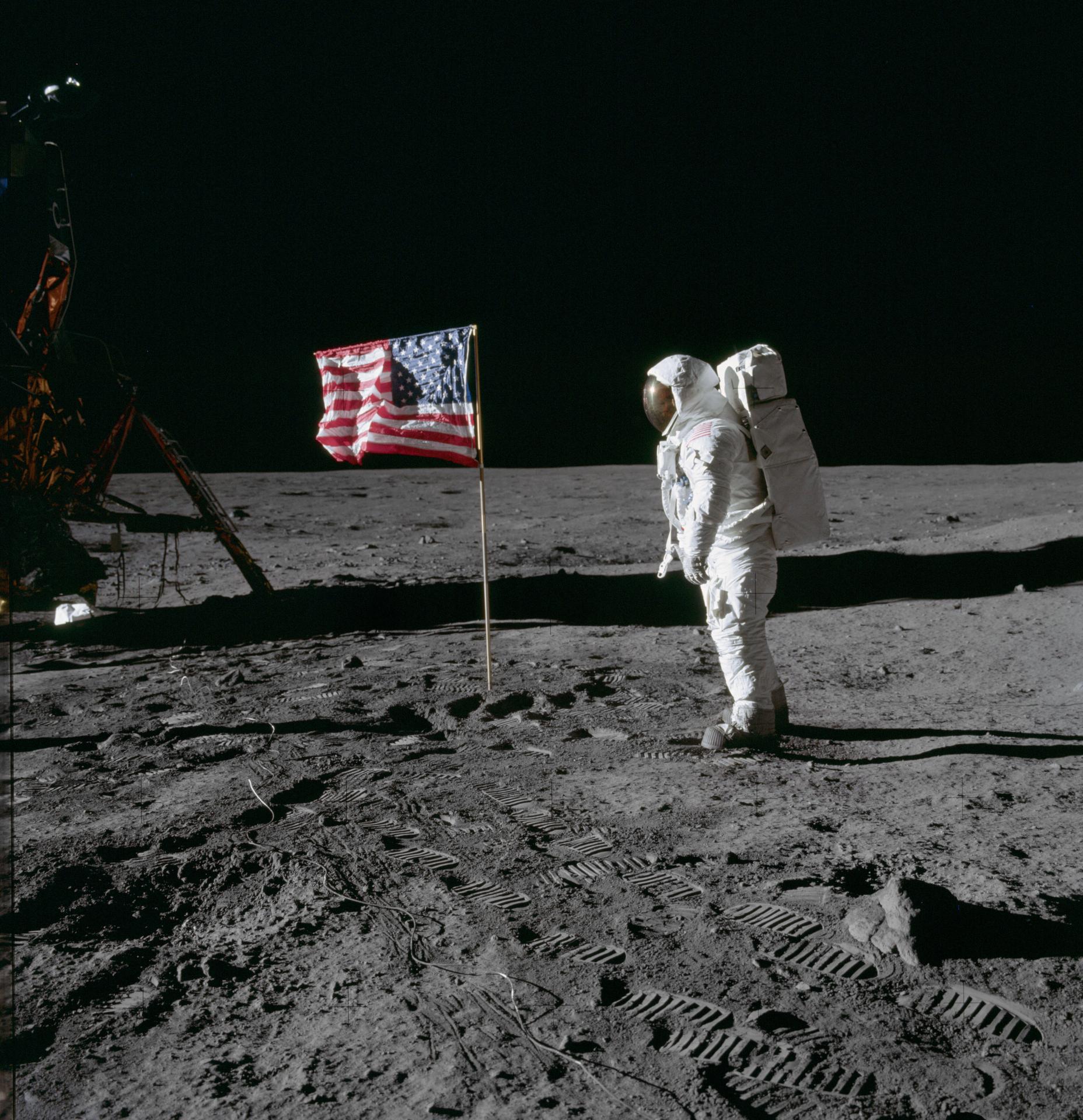

Stuart Whatley (’07), co-author of a new book on technology’s limitations. Photos courtesy of Whatley and NASA

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Whatley wound up co-authoring several pieces with Agar while working as a senior editor at Project Syndicate, an international media organization where he oversees PS Quarterly and edits a number of Nobel laureate economists. The duo made the case that easy fixes through new technology will not save us from threats such as disease outbreaks or climate change. They contend that such thinking can create a moral hazard, where people delay changing their behavior in ways that have been proven to help over the long term.

More recently, they connected with Dan Weijers, another New Zealand ethicist who researches wellbeing and new technologies. Together, they have written “How to Think about Progress: A Skeptic’s Guide to Technology,” due out in early November. The book explores whether optimistic claims about technology’s potential stand up to such challenges as climate change, pandemics, cancer and loneliness.

Wake Forest Magazine Managing Editor Kelly Greene (’91) recently caught up with Whatley to hear his thoughts on techno-hype and futurism. The conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kelly Greene: Congratulations on your upcoming book. How did you get interested in technology’s limitations for fixing our problems?

Stuart Whatley: My other interest has always been work and leisure and what we’re all doing with our time, and I interviewed Nick (Agar) about what economic growth and material progress gets us, and in what ways are we putting too much weight on technology to fix or give us everything. He’s been a long-time follower of the hype that comes from Silicon Valley types. So, we realized we had the same kinds of views from different angles, and he reached out to me about helping to write a book that would be more accessible for students and a general audience.

For me, the big thing is sort of a philosophical point that is very Aristotelian — this distinction between the ends and the means. Technology is never going to be an end. It’s a means. We get so wrapped up in improving our means that no one ever stops. This kind of sounds cliché in a way, but no one ever stops to think about what the end is. What are you actually trying to do with yourself? We are only here for so many years. And so, my philosophical basis has evolved toward Epicureanism, which is not just wine and cheese. It’s about living for pleasure. One of the best secondary sources on Epicureanism is a recent book (“Living for Pleasure: An Epicurean Guide to Life”) by a Wake Forest professor, Emily Austin. It’s a great primer.

Professor of Philosophy Emily A. Austin. Photo courtesy of Wake Forest

I’ve written a few other things recently on that. One (“The delusion of having a meaningful job”) is sort of provocative. It’s about the idea of everyone trying to find purpose at big corporate jobs that can’t possibly have it. That one was funny because I heard from a lot of people who were like, “I love this, but I couldn’t share it on LinkedIn because my boss would see.”

KG: Did you and your co-authors travel to meet each other?

SW: They’re in New Zealand, and I’m in Cary (North Carolina). We’ve never met in person. It was a Zoom thing, and the hours are weird. A lot of it was before I had my first child. Now, it’s right in the middle of dinnertime. They’re more than 12 hours ahead. Someday, we’ll meet. Springer Nature, our publisher, does a lot in the U.S. They publish Nature. But it’s based in Berlin.

Nick would kind of come up with core stuff, his core philosophical points. And then I did a lot of the history and economics and then also just rewriting his stuff to make it more journalistic in how it read. So that was the collaboration. We used a lot of metaphors, a lot of plain language, just kind of following the rules of my day job as an editor. What I do every day is turning academic writing into something that a general audience will want to read.

KG: How did you all come to believe that, despite the real technological marvels we have experienced, scientists and entrepreneurs are promising too much too fast?

Co-author Nicholas Agar

SW: Nick was diagnosed with diabetes in the early ‘90s, and so he knows exactly what progress and benefits diabetes patients have seen since then, which is both some and none, kind of depending on how you frame it. We haven’t cured it, but the devices that you can use for monitoring or administering insulin have gotten better. But that’s where we get into the whole normalization thing. If you’re in 1990, you would love to have the technologies from 2024. But if you’re diagnosed today, you’re going to hope for a cure 30 years from now. It’s the equivalent of going from an iPhone 10 to 15. When the iPhone 10 came out, nobody knew what they were missing yet in the 15. So, it’s all relative.

A lot of what we do in the book is this time travel of what we want from technology today and what we can actually expect 10 years, or however many years, from now. And even if we get it, will we feel as satisfied as we think we will today? Probably not. Some of us remember the days before the internet or iPhones, and we know that iPhones are incredible technologies, but we don’t remember necessarily being less happy. It was different, but it wasn’t necessarily better or worse. And so, there’s a lot of this kind of mental time travel that we try to get people to do.

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin saluting the flag at Tranquility Base

KG: Do you think we put too much faith in technology?

SW: It’s basically our modern religion. It’s like we have faith in technology now to give us everything we need. That whole story is based on this idea of the moon landing. We said we would do it, and we did it. And so that’s the story. We’re always telling ourselves that anything we’ve set our minds to engineer our way out of we can. And that whole narrative just kind of ignored all the promises that people in earlier generations made for technology that never came through. We only remember the successes. We think that whatever we set ourselves to do now we’ll succeed at.

But we shouldn’t even assume that. When Nixon started the war on cancer, they thought they would have the cure in five years, and obviously that didn’t happen. It’s been 50 years, and cancer incidence rates are similar. Some cancers have become more manageable. It’s far more complicated than people in each generation thought it would be. That’s our big counter example. It’s not the only one, but we feel the most powerful.

The point is not to be a wet blanket, but to use these counter examples to show why a lot of the hype that we hear, especially from Silicon Valley types and politicians, is not healthy to believe. We’re trying to give people a different perspective because, at the end of the day, there are opportunity costs and risks to just buying into that. When you let visionaries like Elon Musk, with his Mars mission, tell you what the future’s going to look like, they’re not just making predictions, they’re actually shaping what people invest in today. Predicting a future can become shaping the future, and we think more people should have a say in what the future is going to look like than a few billionaires. So that’s another motivation for the book — democratizing the future.

President Richard Nixon signing the National Cancer Act of 1971. Photo courtesy of the National Cancer Institute

KG: Why do you think it’s important to throw cold water on the optimism?

SW: There is moral hazard involved. A few years ago, there was this hype around nanobots that could be deployed into the atmosphere and eat all the carbon we want. You get people like Bill Gates pumping various yet-to-be viable technological fixes to problems, and if people start to believe, especially people in decision-making positions like politicians, they won’t invest in more boring things that have been proven to help, like installing solar panels and eating less red meat.

KG: You could take this argument all the way back to the invention of agriculture, which brought infectious disease and, in some cases, malnutrition. How do we deal with the downside?

SW: Clearly technological progress is not synonymous with human progress. It’s complicated. The Industrial Revolution was good for a few robber barons, and it was horrible for a lot of people for decades, eventually leading to the Progressive Movement. It took public policy interventions and people realizing the nature of the problem. They did not believe that the technology and economic growth would sort itself out for the benefit of society overall. That’s another angle to the book, the faith in the promise of technology and that the whole concept treats humanity as one unit when it does not. We’re all individuals, and there are winners along the way. And you can’t just assume that one generation can be sacrificed for a future one. Ethically, these things are not so straightforward.

IBM ThinkPads were issued to all students in Whatley's day. Illustration by Dante Terzigni

KG: Backing up a bit, would you please share a bit about your experience as a student at Wake Forest? You majored in history, right? And you were here in the era where everyone was carrying around their IBM ThinkPads, right?

SW: I was a history major in ’07. Then I went to Atlanta for a year just working at a law firm, thinking about doing that. But then I started writing op-ed type stuff, and I got published in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Wake Forest’s making the SAT optional. And I thought, “Oh, maybe I’ll do journalism instead.” So, I started applying for internships in DC where my aunt and uncle lived, and I ended up the opinion editor at the Huffington Post, and that took me to New York. I left in 2017 and have been here since.

I remember the ThinkPad being a glitzy selling point at the time I was applying (to Wake Forest). I guess we were the youngest digital immigrants, or nondigital natives. I definitely grew up playing video games, and we had technology, but the internet was not there when we were kids. We were in college when Facebook was rolled out on college campuses, and we were one of the campuses. So, I’m sure there was a confluence of influences on me there. I remember one or two kids had Blackberries already, too. We still used AOL Instant Messenger throughout college. That was a big means of communication. Everybody AIMed in class. And then everyone switched to Google Chat. There was a lot of technology, and things changed a lot during those four years for sure.

Our message at the end is to adjust our expectations, not putting so much faith in finding a quick fix. It’s asking, if we don’t get that new technology, what can we do instead?

KG: How do you use, or avoid, technology in your own life?

SW: The problem with being in journalism is that we’re all kind of addicted to Twitter, or X. You kind of had to be. I had it on my phone and deleted it. These things are addictive. I kind of had to be on it sometimes, and it’s been hugely useful for commissioning writers. If I wasn’t in this profession, it would be easier to not be on any of it. I have always avoided Facebook and Instagram.

I am very grateful for the childhood that I had. I’m almost 40. It looks just horrible – the constant online demands of the teenager being self-evidently unhealthy from a mental standpoint. These are specific design choices. As useful as Twitter is for my specific profession, there’s no way I see the case for netting out positive to be an easy one to make. You add in all the things about disinformation and the broader health of civic culture and political life, and it seems pretty obviously negative to me.

KG: What’s the best-case scenario for channeling technology as a force for good in our lifetime?

SW: Our big takeaway is making a distinction between grand progress, like the carbon-neutral nanobots, and what we call normal progress, which would be progress using existing technologies. We don’t have any kind of faith in some breakthrough in the next few years, just the technology we already have. If you assume that you only have that, it changes the calculus of how you choose outcomes.

So, connecting to my other topic, work and leisure, we have the technologies we need to work less and not burn out our culture. But we don’t use them, because we’re too fixated on continued growth or new innovations instead of making the social, political or cultural changes that could make things better.

Our message at the end is to adjust our expectations, not putting so much faith in finding a quick fix. It’s asking, if we don’t get that new technology, what can we do instead? And what you find is that there are usually options. With cancer, in the absence of techno-fixes, the biggest blow by far has been the cessation of smoking. That’s a bigger contribution than anything coming out of the labs.

We’re not saying technology has nothing to contribute. We’re asking, “What happens when you stop putting all your eggs in that basket?” You find more options.

KG: Thank you so much for your time — tonight I’m going to unplug, go outside and read a book.