IN THE FALL OF 1996, back when email, websites and “getting wired” were new ideas, Wake Forest issued a laptop to every incoming freshman. Handing IBM ThinkPads to about 950 first-year students was part of a bold, visionary plan to personalize learning and send technologically savvy graduates into the world.

But what no one fully realized was just how much help some professors would need to do their part in advancing that vision.

Take Patricia Dixon, a music instructor internationally acclaimed as a classical guitarist and expert on the music of protest movements. She had been teaching at Wake Forest for nearly two decades when she was asked to integrate technology into her teaching.

“I was desperate,” recalls Dixon, now retired. “We were musicians and teachers. What did we know about computers?”

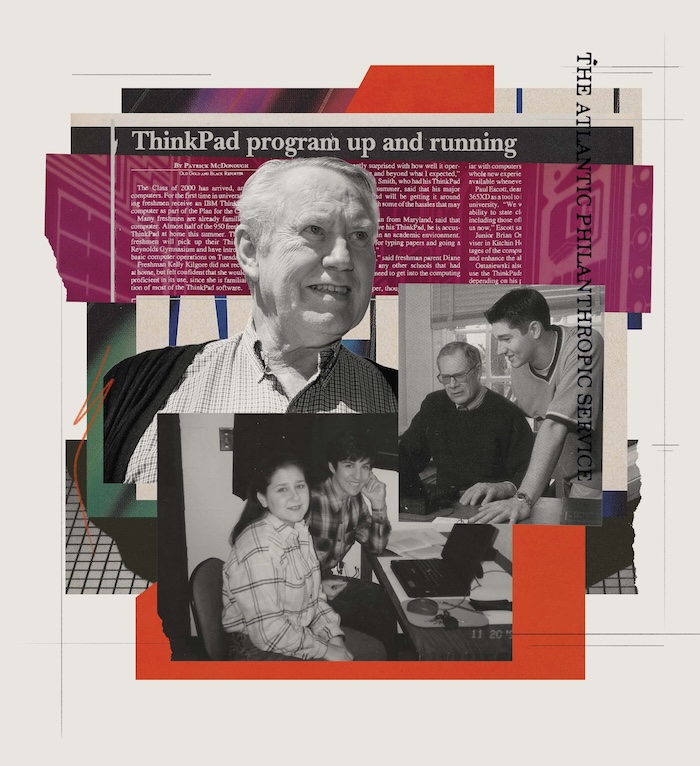

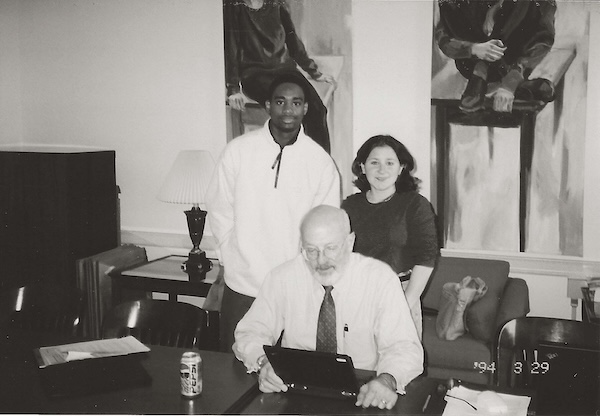

Back in 1996, then-President Thomas K. Hearn Jr. (L.H.D. ’04), left, called Wake Forest’s tech push “unexplored territory for most universities.” Above: Rick Matthews, a physics professor, works with students using ThinkPads in a lab. Rick Matthews photo by Ken Bennett

Other faculty members were digging in their heels. “If we’re going to teach Aristotle, what does that have to do with computers?” argued Bob Brehme (P ’82), a longtime physics professor, now deceased, in a 1995 article in the local newspaper, the Winston-Salem Journal.

Recognizing the widespread need to win over reluctant faculty members and provide tech support to many others, University leaders scrambled to create a technology “acceleration” plan to support the broader “Plan for the Class of 2000.”

This is the mentoring story that, for the most part, hasn’t been told: How a motley, ingenious band of students deemed “Student Technology Advisors,” or STARS, taught their teachers to use computers in the classroom as the new millennium dawned. Through their under-the-radar contributions, the students helped Wake Forest win national accolades — most notably the No. 1 ranking in “America’s 100 Most Wired Colleges” for liberal arts institutions in Yahoo!’s 1999 survey.

And it couldn’t have happened without funding from a secretive billionaire. His identity remained a mystery to many STARS until only a few years ago. Their manager, Nancy Crouch (MAEd ’90, P ’09), recalls that at the program’s start, “the students would ask me who it was, and I didn’t even know.”

Revealed at last

That changed in 2023, when the benefactor died. The students, now alumni in their 40s, learned through social media tributes that philanthropist Charles Feeney, who died at age 92, had provided their backing. Feeney co-founded luxury retailer Duty Free Shoppers, later selling it to LVMH and starting The Atlantic Philanthropies that over 37 years would give away more than $8 billion of Feeney’s fortune.

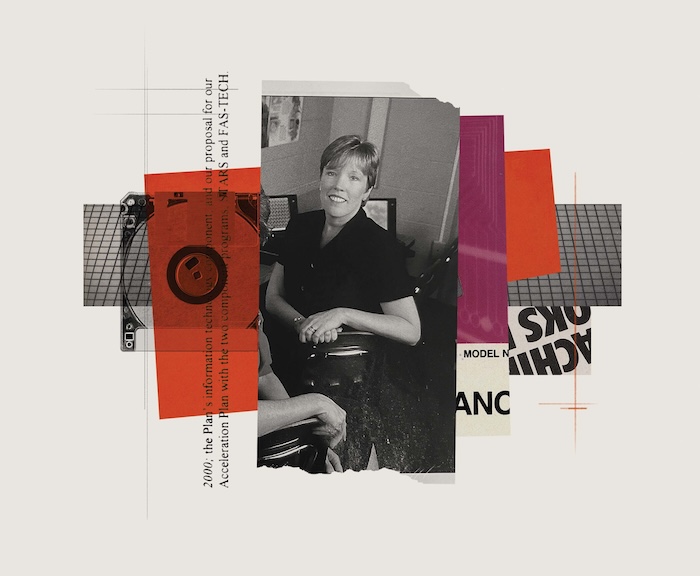

Nancy Crouch (MAEd ‘90, P ‘09), the STARS program’s first director<br /> Photo/Ken Bennett

The first of his Irish American family to go to college, Feeney believed that you should “use your wealth to help people.” Spurning the trappings of wealth in later life, he rented a two-bedroom apartment, flew coach and used a shopping bag instead of a briefcase. His name appeared on none of the 1,000 buildings his foundation funded with $2.7 billion, according to The New York Times, leaving the prestige of naming rights for other donors.

Feeney won praise from billionaire Bill Gates for being “the ultimate example of giving while living.” To investor extraordinaire Warren Buffett, Feeney “should be everybody’s hero.”

Feeney’s operation first connected with the University through parents of Wake Forest students in New York City who hosted a capital campaign event in the early 1990s, recalls Robert D. Mills (’71, MBA ’80, P ’04), a retired associate vice president of University Advancement. The parents encouraged him to invite Raymond Handlan, president of what was then called Atlantic Philanthropic Service; Mills followed up with Handlan to talk more about Wake Forest’s embrace of technology across all academic departments.

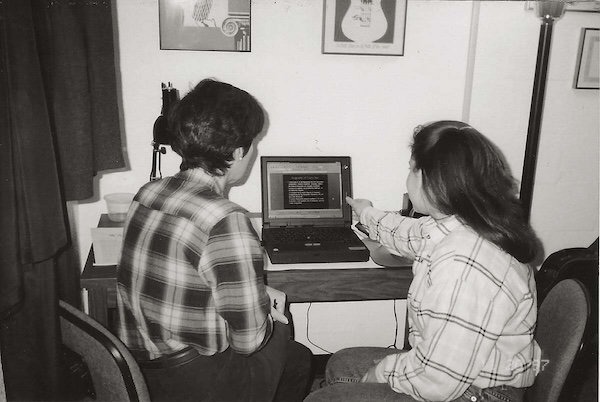

Secretive billionaire Charles Feeney (top) funded STARS through his Atlantic Philanthropies. Joseph Volpe (‘99) helped Professor Ralph Tower incorporate technology into his tax courses (middle). Amanda Epstein Musson (‘00) helped Patricia Dixon, an internationally acclaimed guitarist and music instructor, get comfortable using a computer (bottom). Charles Feeney photo courtesy of Cornell University/ Musson and Dixon photo courtesy of Musson

By 1995, Atlantic — which was starting to support technology initiatives in higher education — had invited Wake Forest to apply for funding, according to University correspondence.

In October 1996, just a few months after first-year students received their own laptops, the University submitted a proposal to Atlantic asking for $1.2 million toward a four-year “Acceleration Plan in the Use of Information Technology.” Wake Forest would “enable the most talented and knowledgeable students to become coaches and consultants to faculty,” the proposal said.

“This is unexplored territory for most universities,” then-President Thomas K. Hearn Jr. (L.H.D. ’04) wrote in a letter introducing the request. “Wake Forest is privileged to be a pioneer.”

Atlantic awarded the grant, and in early 1997 the University tapped Crouch as the program’s first director. She rounded up eight STARS for a test run in the spring semester — including students in the class of 1999 who had not received laptops and needed loaners.

“Life-changing” paychecks

Crouch positioned the role for students as a lucrative one with connections to future opportunities: STARS made $8.50 an hour, which was double North Carolina’s minimum wage. She required attendance at weekly training sessions, often provided by tech giants from IBM to Microsoft, and encouraged the students to apply for summer internships.

Many students today have no idea that their predecessors were thrilled to get IBM ThinkPads weighing about five pounds.

“I had been working at Pizza Inn making $3.75 an hour. (Being a STAR) was life-changing,” says Wes Waters (’01), a STAR who returned to work at Wake Forest in information technology and is now assistant vice president, Advancement Information Technology.

Most of the first STARS came from families of early tech adopters — those with dads who arrived home with computers from RadioShack to tinker with on the dining room table or teacher moms who got early access to the internet and shared it with their kids.

Waters remembers learning HTML with his brother in high school and hosting all sorts of websites. Another STAR, Trinity Manning (’02), was obsessed with learning Microsoft Windows on his best friend’s PC.

Waters remembers learning HTML with his brother in high school and hosting all sorts of websites. Another STAR, Trinity Manning (’02), was obsessed with learning Microsoft Windows on his best friend’s PC.

The STARS all spent time one-on-one with accomplished professors they typically would have interacted with only in class or during office hours. “It created some interesting relationships with our faculty members and provided us an opportunity to engage with them in just a different way,” Waters says.

“We ended up teaching all kinds of these new technical concepts to them, and some of them stuck, but I think we were there to just sort of soften the blow and guide and hold their hands through something that was going to be hard. They just had to go through the reps to get comfortable,” he says.

At first, Crouch found it challenging to get faculty to raise their hands for help, despite their need for it. “They had to apply and tell us what they wanted to work on,” she says, “and they were afraid that what they might say was too elementary.”

“I had been working at Pizza Inn making $3.75 an hour. (Being a STAR) was life-changing.”

Ryan Scholl (’01, MBA ’05) credits the professors who volunteered early on with “being humble and saying, ‘I’m going to open myself up and let you teach me.’ It gave me a lot of confidence as well to say, ‘I can walk in to see this person who is a generation ahead of me and teach them something I know.’”

Videos and footlongs

Rick Matthews, a physics professor famous among students for dressing as Darth Vader to make a point in class, became the program’s “proselytizer,” Crouch says. Two STARS — Susan Boling (’99), who has changed her name to Angelica Rose, and Scholl, now a senior project manager for Wake Forest, helped Matthews create a video library of his visual lessons.

“It is only with classroom demonstrations that students can observe physical phenomena, propose models and test the models they develop,” says Matthews, later named associate provost for information systems and chief information officer, and now retired. Since his physics lessons often happened fast, he wanted students to be able to go back and “watch as often as they like, watch in slow motion and discuss with classmates.”

Rose and Scholl, who had taken Matthews’ class, built a web page where the popular professor freely shared the videos — and for years, the page was believed to be the most visited page on the University’s entire website. It turned out that science teachers and physics students across the country had discovered Matthews’ videos and were watching them, too.

“We went into the classroom and recorded all the demos on video, and we worked on how to do the shots and then posted them online,” Scholl says. “(Matthews) would take one of those foam airplanes and throw it at me in the camera, and you would see how the wind would come over the wing.”

Scholl’s favorite: To describe an equal and opposite reaction, Matthews sat on a cart, put on a hardhat, picked up a fire extinguisher and pulled the pin, propelling him backward.

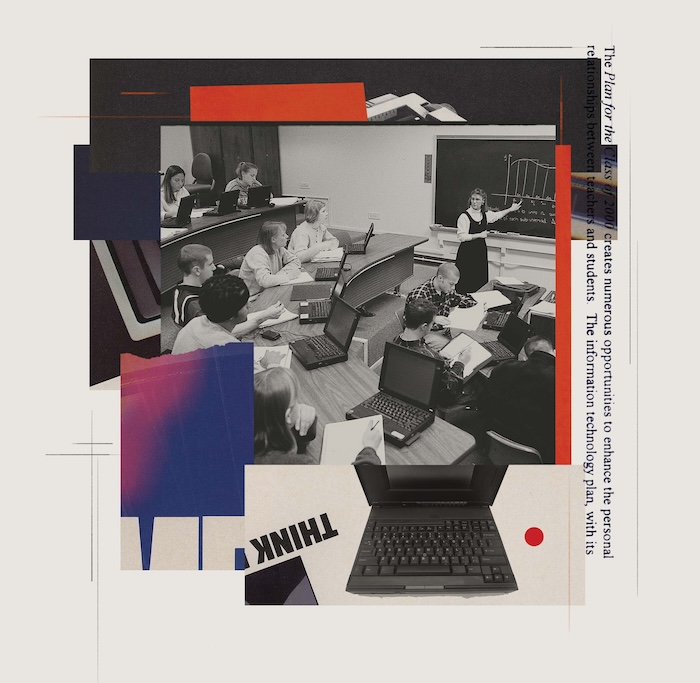

Students had their ThinkPads at the ready in a 1998 math class. <br /> Photo/Ken Bennett

Rose remembers working with Matthews on editing and posting the clips in sessions where “we would just hang out and suddenly go, ‘We’re hungry. Why don’t we go to the Little Red Caboose?’ And then Nancy (Crouch) would come, and (Matthews) would come, and suddenly there would be a bunch of people getting footlong hotdogs.”

Presidential surfing

Seeing the success of early adopters, more faculty started asking for help, and Crouch hired 35 STARS for fall 1997.

“We were just figuring this stuff out on our own, and then we were helping (the professors) come up with creative ways to implement all this new technology to facilitate learning — and trying to discourage them from doing things that would impede learning,” recalls Joseph Volpe (’99). “We’ve all heard of PowerPoint paralysis at this point, but back then, it was new. Some of them started doing every lecture as a PowerPoint, at the expense of group projects and activities, and we had to tell them not to.”

It wasn’t just the professors who sought the STARS’ advice. So did the University’s top administrators, including then-President Hearn. In the fall of 1997, Hearn was teaching a first-year seminar on leadership, and Volpe was assigned to help him integrate technology into his class. But Volpe found himself providing more expansive tech support as Hearn got interested in doing his own online research.

"At the beginning of this project, the majority of the partnerships were concentrated on basic office skills. The faculty simply desired to learn how to use a mouse and create Excel spreadsheets. The same faculty are delving into web design and programming languages."

Volpe, now Labcorp’s senior director for neurology, remembers the day the president’s assistant summoned him to Hearn’s office with great urgency. He recalls Hearn, distressed, saying: “I keep reading about how the internet is this trove of information, but I don’t know how to find things that I’m looking for. …I tried to find out how our women’s tennis team was doing, and what I ended up with was not anything that the president of the University should have on his computer and certainly not anything that our students should be looking at on the internet, either.”

Hearn had typed “college women tennis” into an early-stage search engine, Volpe says. The student found himself explaining that the order of words in web queries at that point influenced the answers, “and that you need to be very careful about what alternative meanings these words imply.” At that point, Volpe redirected Hearn to ESPN.com. (Hearn died in 2008.)

STARS Derrick Thompson (‘03) and Amanda Epstein Musson (‘00) in 1999 with John Anderson (MAEd ’00), then vice president of finance and administration<br /> Photo courtesy of Musson

Confidence booster

As the program became better known, it got easier to attract students. Derrick Thompson (’03) was so enthusiastic about applying to become a STAR that he got his father to drive him to campus from Robeson County, in eastern North Carolina, so he could interview in person in the spring of 1999 — before he even graduated from high school.

Thompson got the job and wound up working so closely on technology projects with John Anderson (MAEd ’00), then vice president of finance and administration, that they frequently ate lunch together — and Anderson, years later, attended Thompson’s wedding.

“He was powerful in the University but really humble when it came to being willing to listen,” Thompson says. “And for me, just a country guy from Lumberton, North Carolina, to be heard and appreciated, and then to be able to add value at that stage of my life, was a confidence booster.”

Derrick Thompson (‘03), standing, with Stuart Bracken (‘03, MSA ‘04), helped create a STARS spinoff, Knowledge 2 Work.<br /> Photo/Ken Bennett

Thompson, who has worked in New York, California and North Carolina for IBM, Citrix, Google and Microsoft, was one of several students who created an outgrowth of STARS called “Knowledge 2 Work.” Through that venture, which lasted several years, they built websites for Winston-Salem’s housing authority and the local United Way, among other nonprofits.

Explosion of ideas

As professors became more familiar with technology’s potential, they challenged the STARS with more interesting projects. Candelas Gala, then chair of the Department of Romance Languages, tapped Erin Anderson Nowell (’00) to help her create a range of resources providing cultural background and context for Spanish literature.

Nowell helped Gala learn how to create online presentations with hyperlinks to examples of music, art and architecture from the time of the literary work, along with the text itself. Next, Nowell taught Gala how to add video clips from popular works, such as “Don Quixote.” They also created online study guides for students to help them prepare for in-class discussion.

“I was very intrigued about the way the technology worked and to be able to find the works and connect them,” Gala recalls. “I thought this was amazing, because in the olden days you had to use slides, and that was the worst stuff. It was static.”

“She just ran with it,” Nowell recalls. “She would have ideas, and we’d figure out how to implement them in the class, and when it would work, she would get so excited. Being a young college student interacting with high-level faculty members on a collegial basis really made a difference.”

The impact

No one could have anticipated how much the experience of mentoring their professors would influence the STARS after graduation.

“I was very intrigued about the way the technology worked and to be able to find the works and connect them. ... (I)n the olden days you had to use slides, and that was the worst stuff. It was static."

In addition to earning generous pay, STARS had access to training in what was then cutting-edge software from the likes of Microsoft, Lotus and Java — and internships with corporate giants in big cities. Amanda Epstein Musson (’00) and Volpe spent a summer in luxury high-rise apartments in Chicago while helping Aon plc get ready for changing over technology for the year 2000, or Y2K, which required many corporations to rewrite reams of code.

Nowell, a Dallas attorney and former appellate court judge, regularly flew in company jets during an internship with a networking contractor, forcing her to face her fear of flying while also providing practice in how to interact with powerful executives.

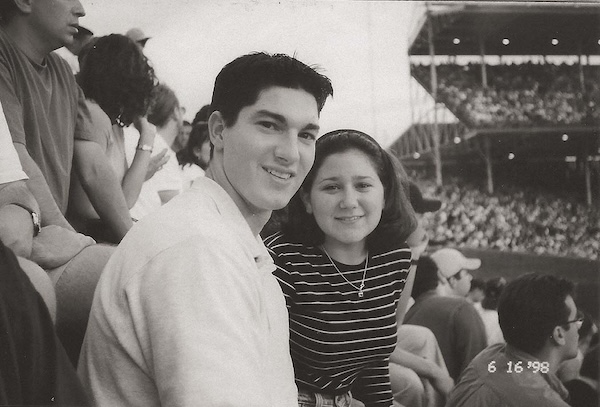

Joseph Volpe (‘99) and Amanda Epstein Musson (‘00) take a break from their Chicago internships at a Cubs baseball game.<br /> Photo courtesy of Musson

STARS helped a few students find their calling: Musson’s internship led to a lifelong career in technology project management, which she continues today with Conduent, a business services firm in Florham Park, New Jersey. (She works from home in Marietta, Georgia.)

Angelica Rose and fellow STAR Erin Honeycutt (’99), who married the summer after graduation, started their first jobs together at Microsoft Corp. in Charlotte before moving to the company’s headquarters in Redmond, Washington. (For Honeycutt, it’s been a lifelong career; Rose left to teach yoga and homeschool their daughter.)

Ron Crouch (P ‘09) and Nancy Crouch (MAEd ’90, P ’09) grew so close to STARS Angelica Rose (‘99), then Susan Boles, and Erin Honeycutt (’99), that they attended their wedding. <br /> Photo courtesy of Rose

Manning remembers feeling “like a kid in a candy store,” because the STARS got to test all kinds of technology tools and toys — remember the PalmPilot? — and frequently got to upgrade their laptops. He developed a knack for quickly building websites in HTML.

Not only did he do so as a STAR for academic departments, from theatre to the sciences, but also as a side hustle for local businesses. When Manning was only a sophomore, one company paid him $8,000 for a website — most of which he spent on a 42-inch flat-screen TV. “It was the dumbest thing I’d ever done,” he says, shaking his head.

He continued building websites, and while working on one for a neighbor who ran a company in the mental health industry, he turned her voluminous paper accordion files into an electronic medical records system. “STARS was my link to all the stuff I ended up doing,” he says.

National recognition

The STARS program itself became a national model: In a 2001 letter to The Atlantic Philanthropies, Hearn shared that “100s of colleges and secondary schools are studying our STARS program, and dozens have used it as a model for developing their own.”

About 250 student-mentors in all participated through 2005, peaking with 40 student advisers in fall 1999. Although the Atlantic funding for STARS ended in 2001, it had sparked funding to double the program’s lifetime thanks to technology companies eager to experiment with training professors, along with students, to incorporate technology into their teaching and student interaction.

Nancy Crouch, the first STARS director, encouraged the students to immerse themselves in new technology.

In a January 2002 letter to The Atlantic Philanthropies, STARS’ second director, Andrea Ellis (MAEd ’04), wrote: “It is amazing to see the difference in the level of expertise in the faculty from 1997 to present. At the beginning of this project, the majority of the partnerships were concentrated on basic office skills. The faculty simply desired to learn how to use a mouse and create Excel spreadsheets. The same faculty are delving into web design and programming languages.

“STARS is a remarkable program,” wrote Ellis, now associate vice president, strategy and operations, and chief of staff to the chief administrative officer of Advocate Health. “The students gained invaluable experience and marketable skills to use outside of the University. … The faculty has embraced technology.”

Role reversal

All these years later, professors and their student mentors can recall in a relaxed fashion the challenging days that required teachers to become students and students to become teachers. Dixon, the guitar instructor intimidated by the new focus on using computers to teach, was paired with Musson, who sang in the University choir and was minoring in music. Musson still remembers the awe she felt listening to Dixon play the guitar — and how that talent contrasted with Dixon’s all-but-paralyzing fear of computers.

Pat and I became very close over the years, and it became more about the friendship that developed while you built a website together.

The student coached the senior lecturer through building her own website, posting music clips for students to listen to outside of class — and followed up with homework to ensure that Dixon could continue building on those lessons.

“It was a role reversal, where the professors I worked with were afraid that pushing the wrong button on the keyboard could cause a catastrophe,” Musson says. “But Pat and I became very close over the years, and it became more about the friendship that developed while you built a website together. … It made the professors less afraid,” she says.

Dixon sums up her feelings toward Musson in one word: “Grateful.”

Eventually, the University stopped issuing uniform laptops to incoming freshmen, as students started arriving with their own computer preferences and know-how. Many students today have no idea that their predecessors were thrilled to get IBM ThinkPads weighing about five pounds. And they certainly don’t know about the student mentors who taught their professors how to use email, make PowerPoint presentations, build web pages and so much more.

For the STARS-turned-alumni called up in that historic moment, one thing will never change, even though a quarter-

century has passed: They remain, and always expect to be, their parents’ and co-workers’ personal help desks.

“I was just on a Zoom call the other day where we had to rename ourselves, and I saw an older colleague trying to figure out what to do,” Nowell, the former judge, says with a laugh. She called her then-fellow judge and walked him through it. “I’m still that person side-texting that it’s OK. We can figure it out and make it work.”